Mein Royalties

Who profits from Hitler’s bestseller?

Jay Worthington

In April 1945, as he contemplated the ruins of the Third Reich from his bunker beneath the Reichskanzlei, Adolf Hitler could at least take some small comfort from the fact that he was a very wealthy man. Defining Hitler’s personal wealth was no easy task, of course, for the distinction between Hitler’s private property and the property of the German state had become thoroughly blurred by the end of World War II. Hitler had acquired his collection of approximately ten thousand works of art largely through the murderous agencies of the Nazi kleptocracy, and some might even question the propriety of the royalties charged to the German government for the right to reproduce his likeness on the nation’s postage stamps. Even if we exclude items like these from his wealth, however, Hitler had earned a substantial fortune through his career as an author. Mein Kampf, Hitler’s mix of autobiography and anti-Semitic rant, was one of the bestsellers of the first half of the twentieth century, and it continues to sell almost twenty thousand copies in English each year.

Mein Kampf had inauspicious beginnings. Hitler dictated it to Rudolph Hess and Emil Maurice in the Bavarian prison of Landsberg am Lech, where they spent 1923–1924 after the failure of the Beer Hall Putsch, and he originally intended to title it A Four and One-Half Year Struggle Against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice: Settling Accounts with the Destroyers of the National Socialist Movement. Under the punchier title Mein Kampf, it sold a relatively modest 9,000 copies in 1925, though sales soared along with Hitler’s political career, reaching 54,000 in 1930 and 850,000 in 1933, the year he became German chancellor. Over the next nine years, the German government purchased six million copies of the work—a copy was given as a gift from the government to every pair of newlyweds in Germany. Hitler earned immense amounts from these sales. By 1945, a total of eight million copies had sold; at their peak, his royalties reached an estimated one million dollars per year.

Until 1939, Hitler also earned royalties on Mein Kampf’s numerous foreign editions—by the beginning of the war, it had been translated into sixteen languages. These publications did provoke some conflict. When Houghton Mifflin published an abridged edition in 1933 under the title My Battle, it met widespread public criticism and spurred a petition to the New York City Board of Education that Houghton Mifflin be barred from selling textbooks to the city, as “an American firm that knowingly lends its assistance in spreading the lying propaganda of a common gangster … should have no right to participate in the distribution of the taxpayers’ money.” The petition was refused, with an explanation by the Board: “The greatest service one can render humanity in general and Germany in particular is to place My Battle within the reach of all, that each, for himself, may see whether the book is worthy or is an exhibition of ignorance, stupidity, and dullness.” Roger Scaife, an officer of Houghton Mifflin who sent a complimentary copy to President Roosevelt, acknowledged the controversy in an accompanying note: “In confidence I may add that we have had no end of trouble over the book—protests from the Jews by the hundreds, and not all of them from the common run of shad … although I am glad to say that a number of intellectual Jews have written complimenting us on the stand we have taken.”

In 1938, Houghton Mifflin addressed the complaints of many of its detractors by licensing the publisher Reynal & Hitchcock to prepare a critical edition. Reynal & Hitchcock commissioned a committee of academics to produce a complete, annotated translation along with 80,000 words of commentary to accompany Hitler’s 320,000-word text. A crisis arose when another American publisher, Stackpole, challenged Hitler’s copyright and announced the preparation of its own unabridged translation. By 1925, when Hitler copyrighted Mein Kampf, he had renounced his Austrian citizenship, but he did not become a German citizen until 1932; on his copyright registration, he described himself as a ”stateless German.” The Copyright Act of 1909, however, only protected foreign authors whose countries granted to “a citizen of the United States the benefit of copyright on substantially the same basis as to its own citizens.” Thus, Stackpole argued that as an author without a country, Hitler could not claim the protection of the Copyright Act. This would leave Mein Kampf in the public domain, eligible to be published by anyone. As the rights of stateless authors had not yet been determined in the US courts, a Federal judge declined to enjoin Stackpole from publishing, and a race to translate ensued while Houghton Mifflin appealed the ruling. On 28 February 1939, fourteen years after the first German publication of Mein Kampf, Reynal & Hitchcock and Stackpole released competing, unabridged translations of the book.

For a few months, there was furious competition between the two publishers. Stackpole advertised that it paid no royalties to Hitler, to which Reynal & Hitchcock responded by promising all profits from the book to a refugee relief fund. Stackpole in turn committed 5 percent of all of its proceeds to refugee relief, while Reynal & Hitchcock scored a coup by getting their edition of Mein Kampf distributed through the Book of the Month Club, which guaranteed royalties of $10,000 to the publisher and $20,000 to its refugee fund. With war imminent in Europe, sales were brisk—Reynal & Hitchcock’s edition alone sold thirty thousand copies in the first month. Then, on 9 June 1939, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that stateless authors were indeed entitled to American copyright protection—in a pre-conference memorandum, Judge Charles Clark, who authored the court’s opinion, wrote, “I think it would be a terrible thing to deny these homeless persons even literary property nowadays”—and Stackpole was enjoined from selling its translation.[1] Houghton Mifflin’s copyright was secure, at the considerable legal expense of $23,000. Eher Verlag agreed to pay half of these costs, and by the time they were recouped from Mein Kampf’s royalties, it was December 1941, America and Germany were at war, and Hitler never did see any payments from the edition.

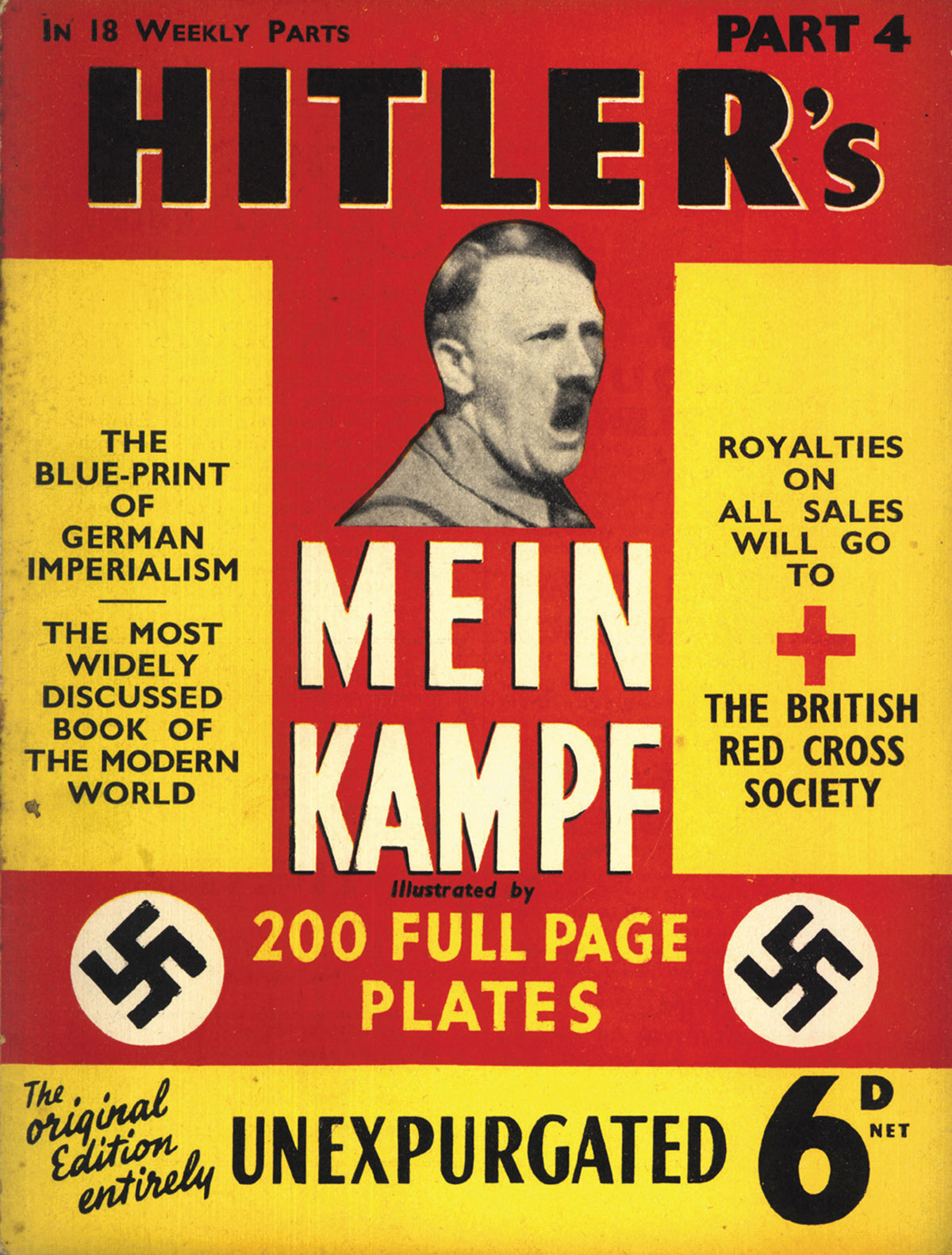

With the outbreak of war, the Allies stopped worrying about Hitler’s copyright. In England, Hutchinson released an eighteen-part serialized edition to benefit the British Red Cross. The book jacket prominently, and without permission, advertised its relationship to the Red Cross. The Red Cross protested the unauthorized use of its name and expressed doubts in a letter to Hutchinson about the propriety of accepting “tainted money,” but it ultimately decided to receive the edition’s £500 in royalties. In the United States, matters were handled more directly. The US government, invoking the Trading With the Enemy Act, seized all royalties due Hitler and dedicated them to the War Claims Fund, which assisted war refugees and American prisoners of war. By 1945, more than $20,000 in royalties had been collected.

When the war ended, publication of Mein Kampf in Germany became illegal. The Allies transferred the non-English rights to the German state of Bavaria in 1951, but Bavaria has not used them as an ownership interest in the traditional, property-based sense of copyright. Rather, it has treated them as a mandate to restrict the spread of the book, and it has consistently attempted to prevent foreign editions from being published. In 1992, for example, when the Swedish publisher Kalle Hägglund published Mein Kampf, Bavaria filed a complaint in the Swedish courts. A lower Swedish court agreed that Bavaria’s copyright had been violated and ordered that the publication be halted. In 1998, however, the Swedish Supreme Court refused to recognize Bavaria’s copyright, but it ruled that someone’s copyright had been violated, and the court upheld the authority of the Swedish public prosecutor’s office (which had joined the case) to enforce that unknown copyright holder’s interests. The edition did not return to bookstores. In rare cases, Bavaria has refrained from intervening, such as a 1995 critical edition published by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and in those instances it has refused to collect any royalties.

The American government, in contrast, continued to collect royalties on Mein Kampf for decades after the end of the war. Houghton Mifflin kept the book in print, and by 1979 the War Claims Fund had collected $139,000 from sales of Mein Kampf. Houghton Mifflin did not pay these royalties without complaint. In a 1979 letter to the Justice Department, it argued that without a reduction of the royalty rate, rising production costs would force it to raise the hardcover price of Mein Kampf from $15 to $19.95, “[which] seems to be flying in the face of President Carter’s anti-inflationary policies.”[2] The company requested that the US reduce the royalty from 15 percent to 10 percent. In the ensuing negotiation, Houghton Mifflin ended up purchasing the American rights to Mein Kampf from the Office of the Alien Property Custodian for $37,254. Over the next two decades, with sales of approximately fifteen thousand copies per year, the best estimate is that Houghton Mifflin realized profits of somewhere between $300,000 and $700,000 on its 1979 investment of $37,254. With the publication in October 2000 of a U.S. News and World Report story detailing the history of its publication of Mein Kampf,[3] however, Houghton Mifflin announced that it would donate all of its accrued Mein Kampf profits to charity, and it continues to give away all of its profits from the book today.

The postwar history of Mein Kampf in England is simpler. It was out of print until 1969, when Hutchinson re-released a wartime translation by Ralph Mannheim. Hutchinson seems to have learned from its mishap with the Red Cross, and from 1975 until 2001, the royalties of approximately £100,000 were donated to a secret charity. That charity was revealed as the German Welfare Council in 2001, when Edzard Grause, its chairman, publicly announced that it would no longer accept the money: “When we agreed to the arrangement, the generally accepted view was that there was a moral obligation to pass the money to Holocaust victims, but no Jewish charity would take it. … This charity was chosen because of its work with Jewish refugees from Germany, but their number has diminished greatly over the years; most have died of old age. The problem now is that no one wants anything to do with the money.”[4] Finding a new charity that will accept the money, however, is not Hutchinson’s problem any more. In 1989, Random House acquired Hutchinson. Then, in 1998, the German publishing conglomerate Bertelsmann bought Random House, and with it the English rights to Mein Kampf.

Thus, perhaps the most virulent document of twentieth-century nationalism is now loose on the seas of globalization. So long as it does not sell the book in Germany, Bertelsmann’s acquisition breaks no laws. Until 1999, however, an English translation of Mein Kampf was the second-ranked bestseller on Amazon.com’s German website before complaints from the German government and the Simon Wiesenthal Center led both Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble.com to block German sales. As a co-owner of Barnes & Noble.com, Bertelsmann is of course well-versed in the difficulties of defending national borders against the incursions of a book. Even, perhaps especially, one with a consumer advisory—“evil book”—on the cover.

- The Stackpole edition was allegedly used as the basis for a pirated Chinese edition printed in Formosa in the early 1940s.

- <www.fpp.co.uk/Hitler/MeinKampf/HoughtonMifflin.html> Accessed 30 July 2012.

- David Whitman, “Money From a Madman: Houghton Mifflin’s Mein Kampf Profits,” U.S. News & World Report, 16 October 2000.

- Charlotte Edwardes and Chris Hastings, “Jewish Charity’s £500,000 from Mein Kampf,” The Telegraph, 17 June 2002.

Jay Worthington is a lawyer in New York City. He is also one of the founders of Clubbed Thumb, an independent theater company in New York, and editor-at large at Cabinet.