Phases of Life 2: The Family Room of Tomorrow

The domestic dreamspace, after the bomb

Joseph Masco

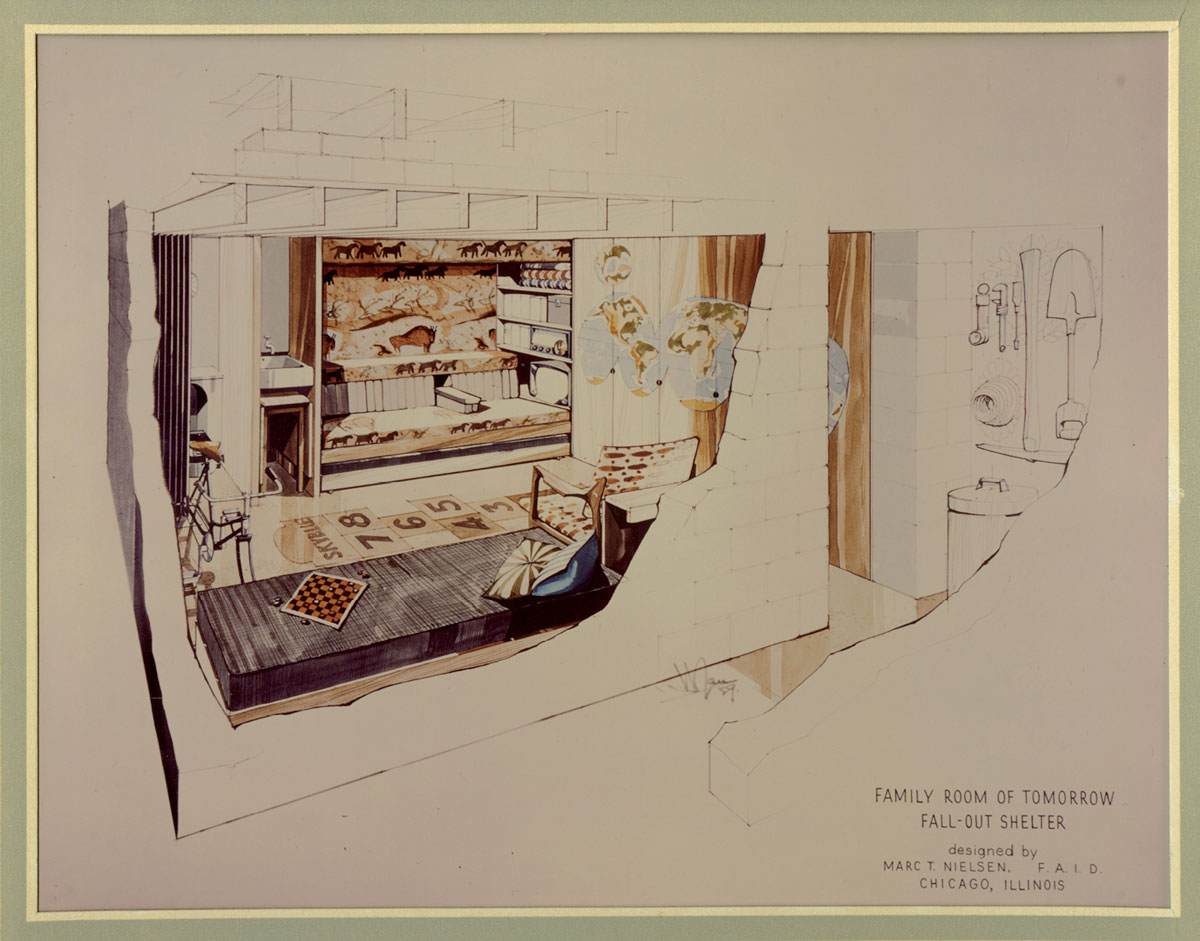

We forget today how fundamentally the atomic bomb changed our relationship to the future. “The Family Room of Tomorrow” recovers this future/past, revealing a moment when Americans first needed an explicit promise of a tomorrow. With its leisure chairs and board games, its neatly stacked cabinets and electronics, the image seems to offer everything necessary to bring a family together. Indeed, it presents a domestic space already charged with the expectation of shared intimacy (in games, conversation, and contemplation), and as domestic refuge, requires nothing—except perhaps a window to the outside world.

Part of a larger 1950s Federal Emergency Management Agency project to convince citizens that a nuclear war was winnable, the Family Room of Tomorrow aims both to normalize and beautify the nuclear present (i.e., note the decorative throw pillows). By offering voluminous plans and diagrams that could elevate the dutiful citizen to survivor in a moment of ultimate crisis, the US civil defense program sought to shift responsibility for domestic defense from the state to its citizens. Officials wanted to mobilize America’s frontier spirit to engage a looming nuclear future, arguing that with preparation, training, and the proper commodities, the American “can do” spirit could overcome any obstacle or turn of events. In promoting a dual-purpose American home—a beautified bunker that was both good for family togetherness and safe from thermonuclear attack—the Family Room of Tomorrow presents a basic paradox of the nuclear age. We can see this most clearly in the two images adorning the walls of this imagined space, the cave painting and the geopolitical map. One suggests a return to a prehistorical state, a world untainted by electricity or the nation-state, while the other presents a globe as coordinated as any family room pantry, contained and organized under a unified nuclear present. According to the propaganda of the civil defense program, the imagined inhabitants of the Family Room of Tomorrow would know that the bomb would produce at worst merely an alternate future, presenting an opportunity to rebuild the world on new, if possibly radioactive, terms.

This 1950s Civil Defense Project, however, quickly failed an American imagination undermined by the escalating Cold War arms race. The terror of the bomb inevitably short-circuited such a calculated deployment of pasts and futures by the state. Citizens came to understand that if there were any survivors of nuclear war, they would be produced as much by sheer luck as by civil defense measures, and that those not living in a suburban dream space would be literally locked out of the Family Room of Tomorrow. From another perspective this image of the future has proved prescient: for today, citizens are once again being asked by the state to fortify their home spaces with duct tape and canned goods, to coordinate pantries and escape routes, to contemplate the home as domestic bunker. In this way, the Family Room of Tomorrow still has a claim on our collective future: for in contemplating its unpopulated terrain, we engage a domestic dreamspace that promises that our families will always be together regardless of time, place, or war, and that checkers and hopscotch are all we need to negotiate our uncertain tomorrow.

Joseph Masco teaches anthropology at the University of Chicago, where he writes about technology, politics, and aesthetics.