Doppelgänger/Doppeltgänger

A word effaced by its double

Paul Fleming

Rome knew how to treat a doppelgänger. When the Emperor Septimius Severus died in 211 CE, an effigy was fashioned in his likeness, dressed in the deceased’s clothes, and laid on the royal bed. Here the ceremony began, not for the dead man, but for the doppelgänger: “the effigy, treated like a sick man, lies on his bed; senators and matrons are lined up on either side; physicians pretend to feel the pulse of the image and give it their medical aid, until, after seven days, the effigy ‘dies.’”[1] Already in the age of Antonius (83–30 BCE), the aides and physicians would attend to the emperor in effigy, while the real body was inauspiciously cremated and placed in the mausoleum. It was only upon the second “death,” after the doctors had done everything they could for the doppelgänger, that the official phase of mourning began, and a second, public funeral procession now took place, complete with a cremation of the effigy. Thus did the Romans—and later medieval France and England, where the tradition continued—prove that while the king may die, the King never dies. The effigy was intended to keep the demons at bay, not however for the dead man’s soul (which had to fend for itself), but for the dignity of the institution of royalty, a dignity embodied in the doppelgänger.

Like the proverbial “other guy,” the doppelgänger has always had it better than the original, of which it is a (near) exact copy. The doppelgänger is an effect-machine, generating sensations of the comic, the uncanny, and the terrifying for the one confronted with his second self. In this respect, royalty also had its advantages: in having their likeness fashioned post-mortem, they were shielded from the creepiness of a doctor feeling for an effigy’s pulse. Even in its first literary employment as an instrument of the comic, the doppelgänger occupied the desired position, for he was never the butt of the joke. The comic playwright Plautus (254–184 BCE) seems to be the first author who made a career out of doublings. Throughout his oeuvre, a doppelgänger (either as lost twin or a god in man’s garb) creeps unbeknownst into a man’s life, steals his identity, sleeps with his partner, and throws the whole town into confusion as to why he is acting so strange—a barrel of laughs—until a final scene of confrontation and recognition. Within literature, this tradition of comic confusion, often coupled with the political intrigue of a tyrant being replaced by a benevolent double (the prince and pauper motif), held sway until the advent of the modern subject. With Descartes’s division of the world into cogito (mind) and res extensa (everything outside the mind, including one’s own body), the doppelgänger began to take on haunting, uncanny qualities in literature, as the body became a gesticulating machine mocking the ego. The equivalence between the two halves of the doppelgänger was therefore no longer based solely on physical attributes, but also included the relationship between the body and the mind.

Jean Paul, the author who coined the term doppelgänger (“one who goes twice”), got the most literary mileage out of cabinets of wax figures and the body as one’s own personal effigy. In his first novel Invisible Lodge (1793), he sends the young hero Gustav through a gallery of wax dolls that double all the characters in the novel (perhaps the strangest manifestation of a “novel within a novel”), as his guide comments: “They never speak for all eternities—they are not even once among us—we ourselves are never together—flesh and bone grates stand between the human souls.”[2] Such a Cartesian doppelgänger is grounded in the notion of the human subject being composed of two irreconcilable parts: body and I, machine and spirit. And it is the deafening muteness of the waxen double that reveals the truth of the mind as equally cut off from its bodily manifestation and other souls. The result of this unbridgeable divide between the material and immaterial is a profound experience of horror in the face of both the body and the mind.

Viktor, the protagonist of Jean Paul’s second novel Hesperus (1795), is the poster boy for this Cartesian problem. Viktor views bodies as “the flesh statues in which our spirits are chained.”[3] Unlike the kings who had the wisdom to die before allowing an effigy to be fashioned in their likeness, Viktor, like so many of Jean Paul’s protagonists, makes the unwise decision of having a wax double made of himself while still alive. As he stares at his second, always already dead self in the twilight of half-slumber, Viktor recalls the childhood trauma found in ghost stories and, more concretely, in the mechanical gesticulations of his own body:

He shuddered in the face of this flesh-colored shadow of his I. Already as a child, it was especially the ghost stories of people who saw themselves that touched his breast with the coldest of hands. In the evening before going to bed, he often gazed so long at his quivering body that he separated himself off from it and viewed it as an alien figure standing and gesticulating so alone next to his I. Then, trembling, he laid himself together with this alien figure into the grave of sleep. The darkened soul felt like a Hamadryad grown over by the supple rind of flesh. Thus he felt the dissimilarity and the long space between his I and its rind; he felt this deeply when he gazed upon another’s body and, more deeply, when he gazed upon his own.[4]

Viktor experiences the Cartesian nightmare, in which the cogito and res extensa try to settle into one bed, one space, for a night’s sleep. Viktor’s dissecting gaze severs his being into two distinct, foreign entities, crowding the bed with a flesh rind and a mind trying to get its head around it. And yet it is not the spirit that is haunting. More strangely, it is the body that haunts the spirit, casts a shadow across it, darkening the soul. The movements of his body are removed from the expression of his “self,” his inner state; they always belong to an other, even and especially when they are his own. Viktor’s body is literally a “foreign body,” an alien being that accompanies his I, but is not proper to it. Like a machine dancing next to and around the self, the body possesses a mechanical exteriority that hints at the possibility of a body without soul, without a self.

Always willing to crank it up another notch, Jean Paul doesn’t allow Viktor’s nightmare of lucid wakefulness to end there. The uncanny sense of not being oneself, of not being one self, achieves a high point in Viktor’s funeral eulogy to himself in the form of the wax double. The splendor that was Rome is revisited in all its horror, as the living attends to his own effigy:

That is the night-corpse—the ridiculed, the charred man—egos are glued to such petrified clumps and must lumber there within. … I see a specter [Gespenst] hovering about this corpse, a specter that is an I. … I! I! you abyss that retreats deep into the dark in the mirror of thought—I! you mirror within a mirror—you shudder within a shudder! [5]One could not throw oneself—body and I—into a deeper region of abjection. The mystery that was man is revealed as a child’s art project, where the thing called an ego is sloppily glued to ossified clumps of matter, which then clumsily lumbers about like a puppet. Even the releasing of the I from the wreckage of the body does not announce a moment of liberation or transcendence. Rather, the I emerges not as spirit [Geist] but as a ghost or specter [Gespenst] that hovers about the corpse, haunting it, only to retreat into darkness. The I is uncanny within the body; when freed from its “flesh statue” it is even more shuddering to think about. It is but a short step from here to Otto Rank’s famous 1914 study “The Doppelgänger,” the first psychoanalytic investigation of the uncanny effects of seeing oneself outside oneself.

Jean Paul coins the term doppelgänger in his third novel Siebenkäs (1796), and a name is finally given to a concept that has existed for over two thousand years. Unfortunately, the word used by Jean Paul to define the concept of “doppelgänger” was not, in fact, the word doppelgänger. That is, even the word doppelgänger has its doppelgänger. It’s confusing—but so is the story of Siebenkäs. The premise of the novel is also the source of its dramatic problem: Siebenkäs and Leibgeber are friends who look so identical—just a birthmark and a limp separate them—that they decide to complete their “algebraic similarity” and exchange names. Siebenkäs, therefore, is actually not Siebenkäs but Leibgeber, and vice versa. (Needless to say, this problem of nomenclature makes talking about the novel a psychotic affair, a fact that perhaps resulted in Siebenkäs being one of the first novels to be banned by censors for its pointless subject matter and the incomprehensibility of its content.) Because Siebenkäs is not Siebenkäs, he loses his inheritance, thereby dooming his newly celebrated marriage to the bonnet-maker Lennete to poverty and domestic misery. As an advocate for the impoverished, Siebenkäs can’t make ends meet and therefore tries his hand at writing (works with titles that Jean Paul had already published). His drive to write continually runs aground on his good but simple wife’s drive to sweep and clean; each hush of the broom or wipe of the cloth destroys the concentration of the overly sensitive writer. Even when she isn’t cleaning, he can imagine what it would be like if she were, which is all the more deafening. In the end, Job’s throne of suffering is delivered to Siebenkäs’s living room: “In the 12th century one still pointed to the deteriorated dung heap upon which Job had suffered. Our two easy chairs are this dung heap and can still be viewed.”[6] Everything has its double, including Job’s dung heap, which can be found in every furnished apartment. Leibgeber (‘the body giver’) must come to the rescue and save his identical mate from suffering that is biblical. There is only one way out: not death, but the next best thing—faking one’s death. With Leibgeber’s help, Siebenkäs “dies,” rocks are buried in his stead, Leibgeber surrenders his name (which isn’t his) back to Siebenkäs, Siebenkäs (who is now Leibgeber), moves on to a new life, leaving his poor wife to do the same. Whereas the king’s effigy lies in a royal bed accrued with all the dignity of the institution, Siebenkäs looks back at his doppelgänger life and exclaims: “The dream of life is dreamed on a bed that is too hard.”[7]

But as stated above, Jean Paul does not refer to Siebenkäs and Leibgeber with the now standard term doppelgänger. Rather, they are dubbed doppeltgänger, which Jean Paul immediately defines as “the name for people who see themselves.”[8] Never has a neologism been so clearly employed and explained, only to fall into disrepute. Earlier in Siebenkäs the neologism doppelgänger also appears for the first time and means something quite different than a doppeltgänger. In a description of the wedding banquet in the first chapter, the food is so delicious and abundant that “not only was one course [Gang] served but also a second, a doppelgänger.”[9]Gang in German has multiple meanings, ranging from a “walk” to the “course” of a meal; according to Jean Paul, when people “see themselves,” when one “goes twice,’”one is a doppeltgänger; when one has a meal of two courses, in which the second doesn’t come second but together with the first, this is a doppelgänger.

Much like the emperor who has already been cremated and buried, the proper meaning of doppelgänger—the culinary simultaneity of two courses—can no longer protest its usurpation by its effigy and semantic body-snatcher doppeltgänger, which on the level of the letter deviates from it by a mere “t.” The meaning of the word doppeltgänger (“one who goes twice”) has effectively killed the meaning of the word doppelgänger, dressed itself up in its garb, lied down on its bed, and since then been attended to by all as if it were the real thing. While a few German novelists (E. T. A. Hoffmann, Droste-Hülshoff) have properly titled their works “Der Doppeltgänger,” all references to doppelgänger today efface the word’s original meaning. Which is a shame, because now no word remains for the equally important experience of a multi-course meal that is so good that one must have two courses at once, a doppelgänger.

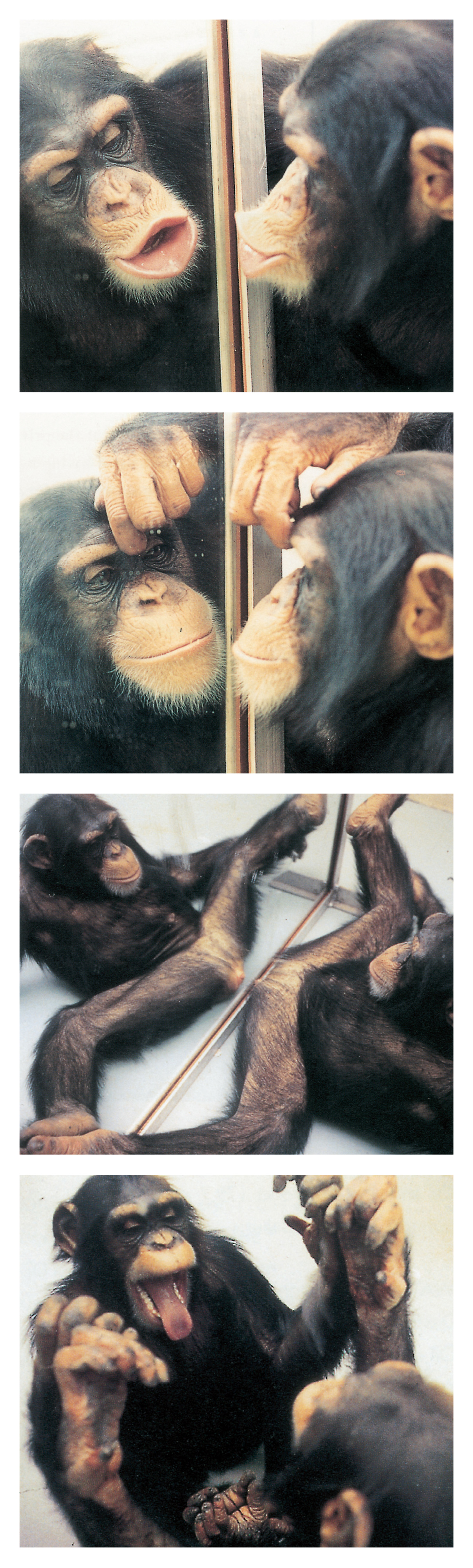

In an attempt to validate my impressions of what had transpired, I devised a more vigorous, unobtrusive test of self-recognition. After the tenth day of mirror exposure, the chimpanzees were placed under anesthesia and removed from their cages. While the animals were unconscious I applied a bright red odorless alcohol-soluble dye to the uppermost portion of an eyebrow ridge and to the top half of the opposite ear. The subjects were then returned to their cages and allowed to recover. Upon seeing themselves in the mirror the chimpanzees all reached up and attempted to touch the marks directly while intently watching the reflection. In addition to these mark-directed responses, there was also an abrupt three-fold increase in the amount of time spent viewing their reflection in the mirror.

Thanks to Professor Gallup for his assistance.

- Ernst H. Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981), p. 427.

- Jean Paul, Sämtliche Werke, vol. 1, ed. Norbert Miller (Munich: Hanser Verlag, 1960 f.) p. 321. All translations are mine.

- Ibid., p. 581.

- Ibid., pp. 711–712.

- Ibid., p. 939.

- Ibid., vol. 2, p. 116.

- Ibid., p. 575.

- Ibid., p. 67.

- Ibid., p. 42.

Paul Fleming is assistant professor of German at New York University. He is currently completing a book on humor and Jean Paul.