Doubled: Five Collaborations

The active agent of individual disappearance

Charles Green

Artists involved in sustained collaborations fold themselves into an elusive extra identity: the double. This double is the phantom body of the collaboratively created identity. Some long-term artist collaborations actually become doubles themselves. British artists Gilbert & George dress alike and, in the early 1970s with metallic paint (removed afterwards with an abrasive household cleaning product) applied to their faces, they looked alike. The double emerges with particular power in artistic collaboration by twins and couples, as a phantom superimposed over and exceeding individual artists. Marina Abramovic’s and Ulay’s bodies changed quite dramatically during their long collaboration and, according to many observers, they became remarkably similar in appearance.

The collaborative double is different in nature to the family or the corporate collaboration. Many artist collaborations exhibit an intense awareness of the creation of an authorial phantom exceeding the identity of the collaborating artists. According to Vitaly Komar and Alex Melamid, who collaboratively evolved a hybrid type of history painting from a combination of Socialist Realist and modernism during the 1970s, “We invented that third person, the third artist, but we never specifically named that third artist.” Alex Melamid cites the Russian literary precedents for the renunciation of one’s own voice in favor of an invented, fictitious identity: “The artist’s ‘name’ is important; it’s a fictional device.” Abramovic and Ulay gave the double a name, identifying it as a spiritual force, “Rest Energy,” insisting that a hermaphroditic identity, independent of them, was created by collaboration.

The double has another significance. It is a characterization of the artistic field generated by the incorporation of others and Others within cross-artist fusions. This is a particularly loaded topic, highlighting the often-elided difference between two models of artistic collaboration. The first model is practical, pragmatic, and subliminally suspicious. It is the popularly held view of collaboration as reconciliation, implying both profit and loss. This bookkeeping sense sees artistic collaboration as a balance. An accounting deficit in one part of the relationship is compensated by a surplus somewhere else—a partnership or a cooperative to which individuals bring something that can also be taken away. The second model, on the other hand, involves the double, but requires an artistic collaboration in which the parts of the relationship merge to form something else, in which the whole is more than the sum of the parts. The parts are not removable or replaceable because they do not combine as much as change. The collaboration itself exists as a distinct and distinctive entity. Such collaboration, in specific cases—and perhaps in more recent task-based collectives such as Atelier van Lieshout or Superflex—is an active act of individual disappearance, born not out of a desire to break through the limitations of the self but from a desire to neutralize the self in order to clear out a useful, new working space.

It is possible to perceive a problem implicit at the core of my insistence that the recognition of difference is not of foremost importance in understanding identity, and this potential identity-based objection to the double needs to be spelled out. First, this is not a dog-whistle call for naïve aestheticism, nor equally is artistic collaboration a good in itself. However, the identity constituted by the second type of collaboration resembles a double (and its members doppelgangers), and the elusive quality of the double problematizes the social-activist potential attributed to collaboration by many contemporary critics. For there are costs in moving beyond the idea of an artist: when unconventional art produced by shifting alliances of “artists” locates itself inside stable discursive frameworks such as art museums, the tension created by the covert preservation of aesthetic validation, combined with the aspiration to escape precisely this validation, is not tenable beyond a short period of time. Doubles are usually unstable and unmanageable entities, not easily domesticated.

We are again in a pluralist moment of art that increasingly resembles the 1970s, during which the essential narrative becomes again double: artists working out how to sustain a critical praxis within the institutions and exhibiting spaces of art, and many of the same artists stretching, expanding and redefining the figure of the artist herself. This parallelism should be understood. It links collaborations that emerged in the 1970s to the art of experimental communities in 2004. For that reason, we asked several prominent artist teams about their first moments of collaboration: to describe when and why they first decided to work together, and what were their recollections of making their first collaborative works of art. Some of those artists no longer work together, and a few exited their collaboration determined never to share space with their collaborator ever again. All remember their work together as a period of great intensity.

Marina Abramovic: I received an invitation to participate in a television program about Body Art in Amsterdam in 1975. The program started exactly on the day of my birthday. The invitation arrived in Belgrade where I was living at the time. My grandmother, seeing the invitation, noted that everything you get on your birthday is important. I arrived in Amsterdam and went straight to the set of the TV program where I did the performance. There, I met Ulay, who was also doing a performance for the same program. When I met him, half of his face was unshaven, short hair, and the other half was made-up, lipstick and long hair. Half man/ half woman. I was immediately fascinated and drawn to him. The same evening, all of the participants had a dinner and I offered everyone a drink because it was my birthday. Ulay stood up and offered everyone a drink as it was his birthday too. I immediately told him I didn’t believe him. He had no identification cards to prove it. Instead, he pulled out his diary, showing me that the page, 30 November, was missing. I could not believe my eyes, for every time I buy a diary I also pull out the page for 30 November as well. The same evening we got together and didn’t separate for ten days, at which point I returned to Yugoslavia. There, I was sick from love and longing. I stayed six months, not knowing what to do, making long-distance phone calls. At the geographic mid-point between Belgrade and Amsterdam, we met in Prague. There, we decided to love and work together.

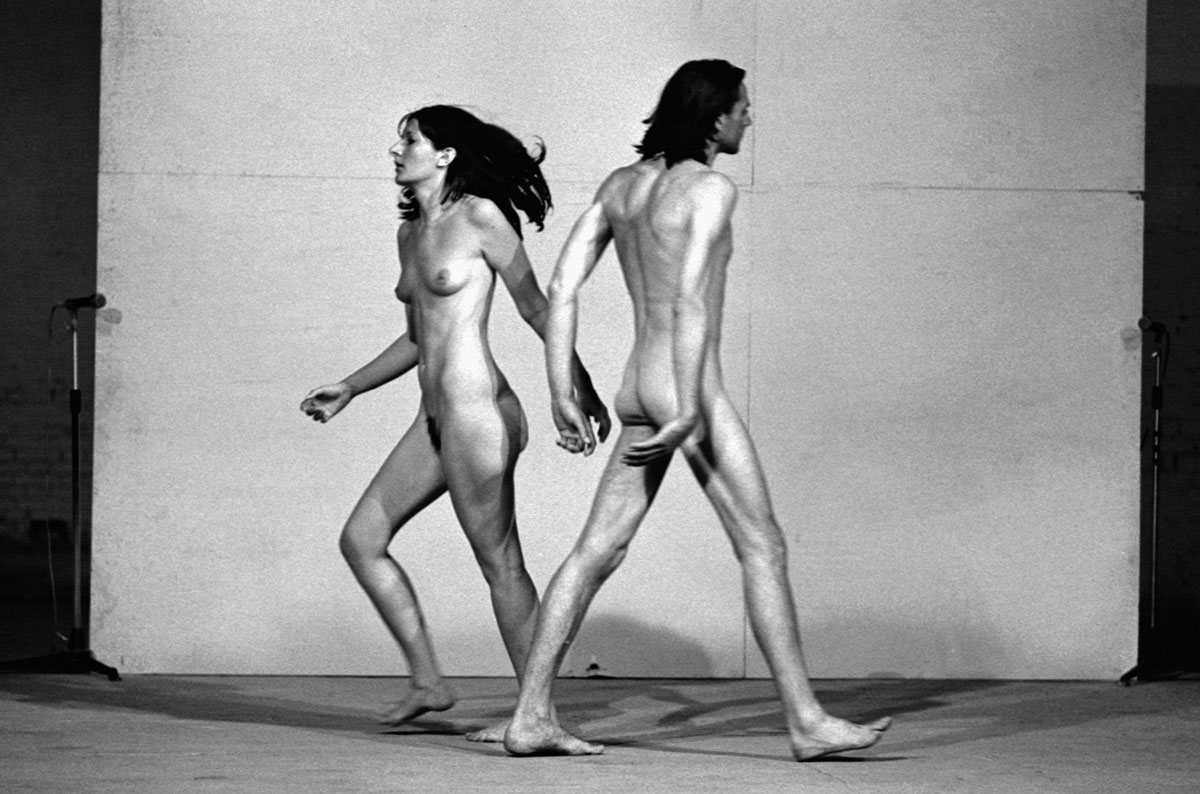

At that point, somehow, my work as a solo artist reached a dead end; I was unsure as an artist of where to go next. Meeting Ulay was a really good solution. We decided to collaborate and create one single work, without questioning ever from whom the idea came, nor even whether the order of our names would rotate from work to work. Our first joint piece, Relation in Space, 1976 (for the Venice Biennale) was crucial for our collaboration. Running towards each other, merging male and female energy into one, became the foundation of our future collaborative work.

Ulay did not respond.

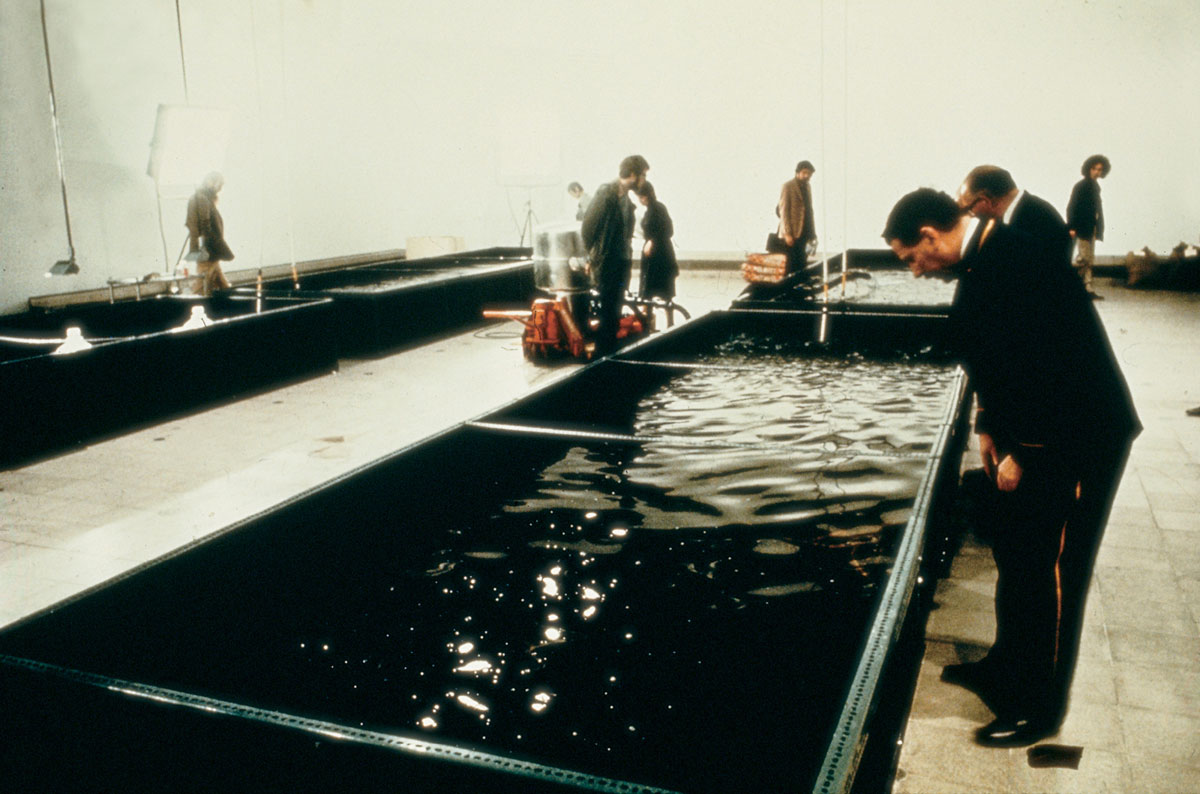

Newton Harrison: We were heavily involved in the peace movement, and subsequently worked together at the Peace Center in Greenwich Village, and at Dillinger’s Living Center. In 1969, we jointly constructed a world map of endangered species. At that point, although we continually consulted each other about my works and about contemporary art in general, we maintained separate careers. Part of the discourse of that period was the idea that a single decision could generate a life’s work.

So we asked ourselves, “What would be a nontrivial single decision?” The rationale for the collaboration was that, alone, I was insufficient to reconstruct real subject-matter in art. By this, I was tipping my hat to the Bauhaus, but the issue of survival was paramount. Smithson and Heizer used earth as material; we feel that our works were amongst the first to deal with ecology in the full sense of the term. The key test for ecological art is the concept of the niche. In a sense, Helen became an artist and I became a researcher, in the process of teaching each other to be the other party. The period between 1970–1971 was the period of performance and research in which we established the research methods and routines possible with collaboration.

Helen Mayer Harrison: My work prior to the 1970s in education and sociology didn’t reach a big enough audience. I worked as New York coordinator of Woman’s Strike for Peace in the early 1960s. My decision to work with Newton was prompted when I was fast-tracked for a prospective Vice-Chancellor position at the University of California. I felt I could achieve social change more readily by working with Newton as an artist than through the slow, incremental bureaucracy of the UC system.

The reaction from other artists was extraordinarily negative. Most assumed that I would disappear, subsumed by male ego. Eleanor Antin said, “How can you let Newton take you over?” People got used to it. By 1976, no one was worried.

Tehching Hsieh: By 1983, when I first decided to work on the one-year artist collaboration with Linda Montano, I had already made three solo “One Year Performances.” I have a strong disposition to do things independently, so perhaps collaboration is the weakest part of my self. I decided to do a “One Year Performance” that would be the most challenging to that weakness. I found the artist Linda Montano, and she was the right person for me to do this collaboration with.

My recollection of making the collaborative work of art that resulted is that as artists we made a powerful piece. But as humans we failed to be collaborative.

Linda Montano: I was living in a Zen monastery in upstate New York when I went into New York City. I saw incredible posters—just a face on a poster from my car—all over SoHo of a man doing an outdoor performance. I then had to find out how to find him. I asked Martha Wilson to help me talk to Tehching Hsieh. I met him at Franklin Furnace and thought I was with a living Master, the vibration of ENERGY is so great in him. I was smitten—in awe, in love! Then he said he was considering a new performance, tying himself to another person for a year. I was happily living in the Zen center but for that opportunity to work with Tehching, for the chance to learn since he chose me to do the piece with him, I left my way of life. Twenty years later, almost to the day, I’m so glad I decided to do this. It is rare to have such an opportunity.

My recollection of making the work is one of heightened awareness, heightened intuitive senses, and a heightened passion for living and relating. Since it involved the psychological danger of proximity and also of potential harm, all synapses were on alert. This piece dislodged a deep hiddenness in me that I eventually unearthed and have dealt with since then. I will forever be grateful to Tehching for involving me in his work of genius.

Anne Poirier: We met a long time ago, in 1965 or so, but exactly when I cannot remember, for I have never had a memory for numbers and dates. I was a student at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, but not a good student because I did not attend many classes. I spent most of my time in cafés and museums, because I thought the decorative arts were quite boring, and because I wanted to be a “real” artist. I was often in the Louvre and I fell in love with Poussin’s painting, Et In Arcadia Ego, 1638–1639, with the young Arcadian shepherds he painted, and with the Greek sculptural heroes and gods. My best friend at school was Annette Messager. One day she asked me to come with her to the printmaking workshop, a very small and quite private studio, with only two boys working there, very jealous of their privacy. They opened the studio door, looked at us suspiciously, and only grudgingly accepted our presence in their sanctuary. One of these guys was a good-looking blond arcadian shepherd named Patrick. I decided to make his portrait, but as a young faun. Since that encounter, we have never left each other, looking at the same images and sharing the same passions. Collaboration came naturally, because Patrick and I had not worked a great deal separately. We took our cue from people in rock music who work together naturally.

The first project we worked together on concerned the Métro. In Rome a few years later, in 1969, our beloved son, Alain-Guillaume, was born. For 33 years, he shared our life and work as well. Since he died tragically, we feel like two orphans, and our life and work will never be the same again.

Patrick Poirier: At the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, my best friend and I were the “owners” of the atelier de gravure, for the teacher only came in one morning a week, and so we only admitted people we liked. One day, two young women knocked at the door: Annette Messager and Anne, who were best friends. I had already noticed Anne—an attractive blonde girl, but she was not often at school. We accepted them with great pleasure ... for instruction only, of course! The following weekend, I went to the Louvre, as usual, and there, by chance or accident, I met Anne. She was sitting in front of the great Nicolas Poussin painting; I took a seat nearby. This was the beginning of our long story, unfortunately colored by the terrible pain caused by the sudden loss of our son in 2003.

Jane Wilson: During our undergraduate courses, we studied at separate art colleges. At the end of our second year (1988), during the summer break, we were staying together and were both doing photography. To begin with, we directed each other in various setups, but in the image titled Garage it shifted to us both being protagonists, and we began to feature in the work together.

Louise Wilson: After that point we returned to our respective colleges and began to travel between them, meeting at Dundee to use the photographic studios, developing and making small work prints, then using the enlargers in Newcastle to produce large black-and-white prints. When it came to our final-year shows, we produced two of everything and exhibited the same work in our respective colleges. The shows ran concurrently and this meant that both institutions had to “collaborate” in their assessment of us.

Charles Green is senior lecturer in contemporary international and Australian art at the University of Melbourne, and senior adjunct curator of 20th- and 21st-century art, National Gallery of Victoria. His books include The Third Hand: Artist Collaborations from Conceptualism to Postmodernism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001). He is also an artist and since 1989 has worked in collaboration with Lyndell Brown.