I Am a Man Who Thinks That I Can Be Me

Another exposé or another thing exposed

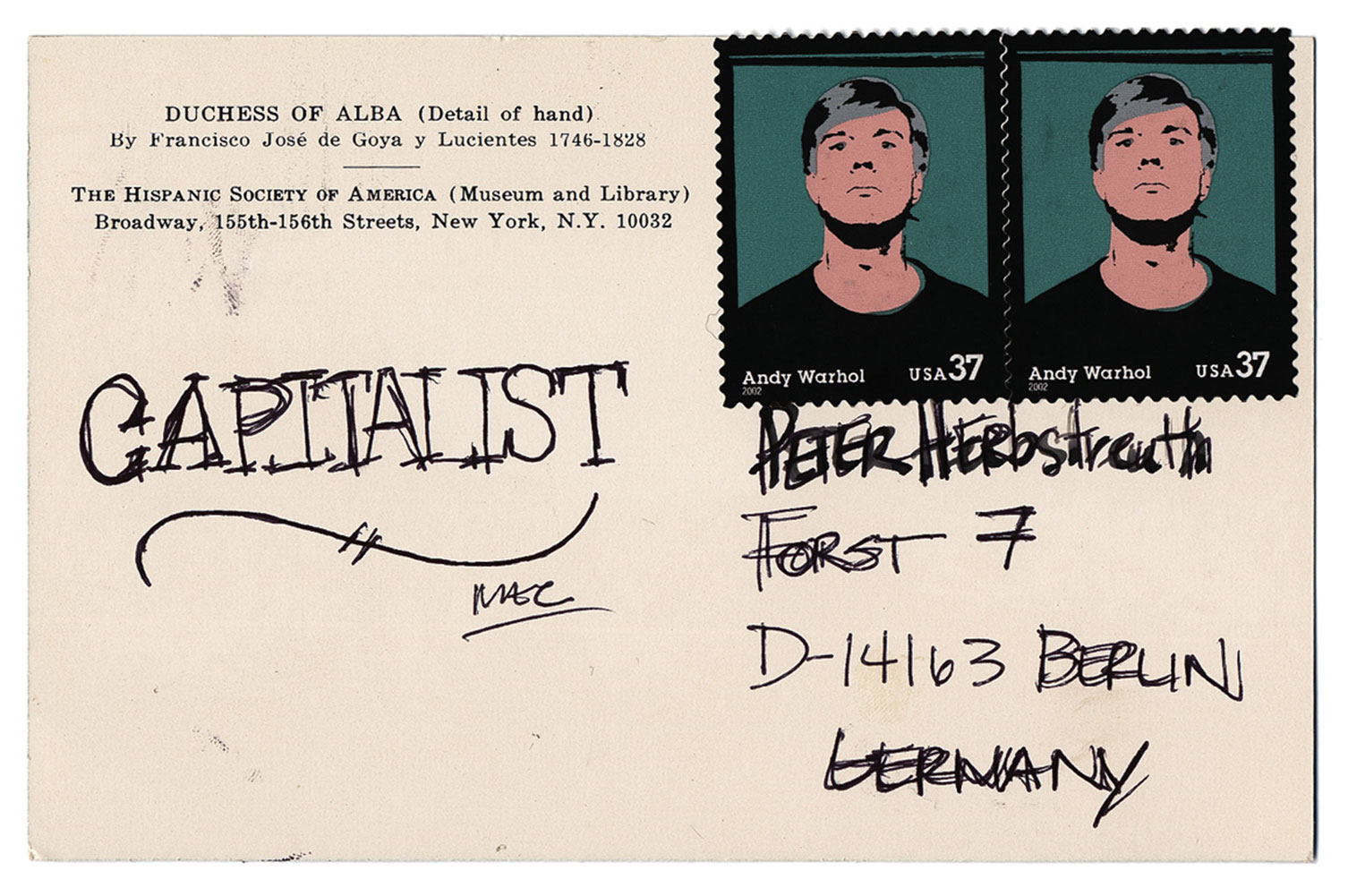

Peter Herbstreuth

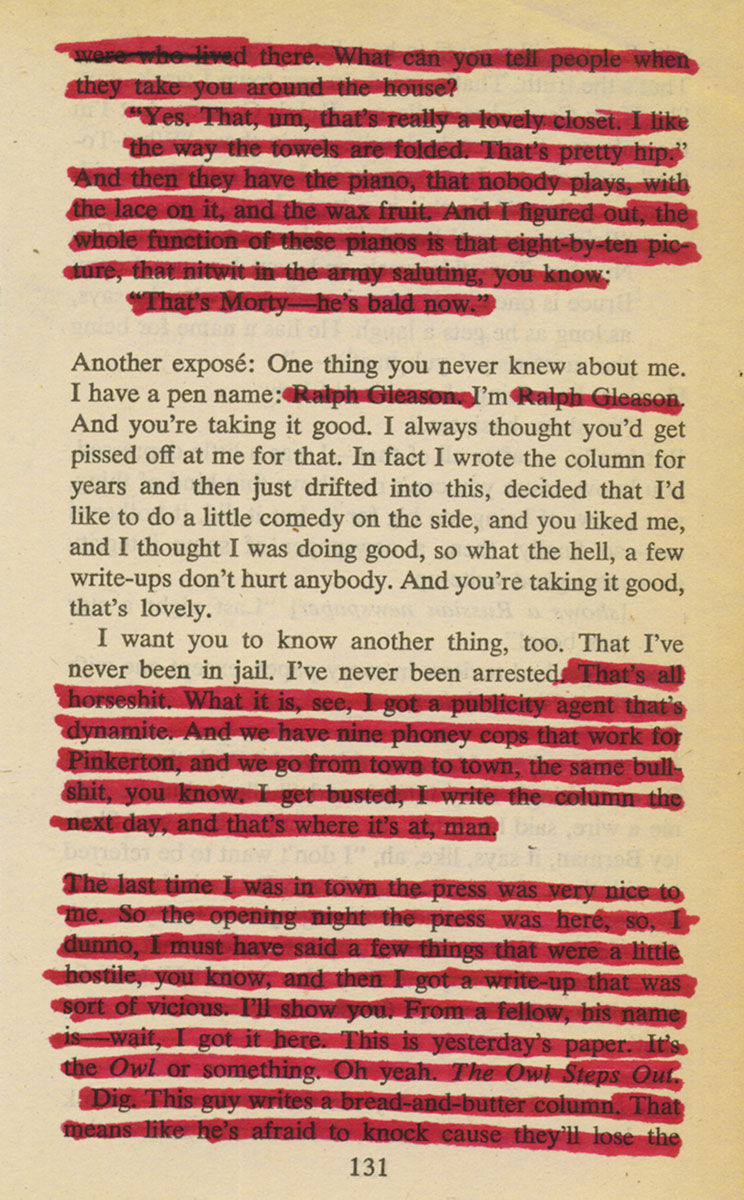

One thing that you never knew about me is that I am a man who thinks that I can be me, and I have a pen name: Peter Herbstreuth. I’m Peter Herbstreuth. And you’re taking it good. I always thought you’d get pissed off at me for that. In fact I wrote the column for years and just drifted into this, decided that I’d like to do a little comedy on the side, and you liked me, and I thought I was doing good, so what the hell, a few write-ups don’t hurt anybody. And you’re taking it good, that’s lovely.

I want you to know this too. That I’ve never been in jail. I’ve never been arrested.

I have listened to Legendary Lenny Bruce about a dozen times since the Friday it arrived, and that means that I have spent approximately 36 hours and 59 minutes trying to understand Bruce’s work as Carroll’s, and vice versa, in order to write this. Most of my colleagues in the critical arena would lament the fact that there is a disorder, a lack of cohesion to what they do, but I would argue that what they in fact share is a clear structure and intentionality not to develop a signature style, which is a very structured and cohesive system, but a system that doesn’t reveal itself immediately. It goes against the current market system in the art world in America, as it went against the then current market system in the comedy world in America. It actually fits quite nicely in the world of philosophy, a place that can deal with conceptual systems that place the invisible in the visible.

Carroll’s work takes time, and the more time you give it, the more it stays with you. In many ways this is very anti- anti-American, which is now very French, and a reason why Bruce was arrested on three occasions—it was just a matter of time. It is like the day following an unexpected, pleasure-filled evening, when you spend the entire next day thinking about why you are still laughing, but not laughing out loud. It is pleasured thinking, not thinking pleasurably, and when you have pleasured thinking about a work of art, it becomes a residue that is like the taste of a ‘98 Barbera, not a ‘97, because everyone knows about the ‘97s. The Italian Giorgio Agamben has written about this paradigmatic philosophical shift, also known as a Copernican turn, from the viewer’s perspective to the artist’s perspective. On my own, I noticed that this is a system where Carroll’s work originates from, and Bruce utilized the same system in comedy. (I, too, am a closeted Nietzschean.)

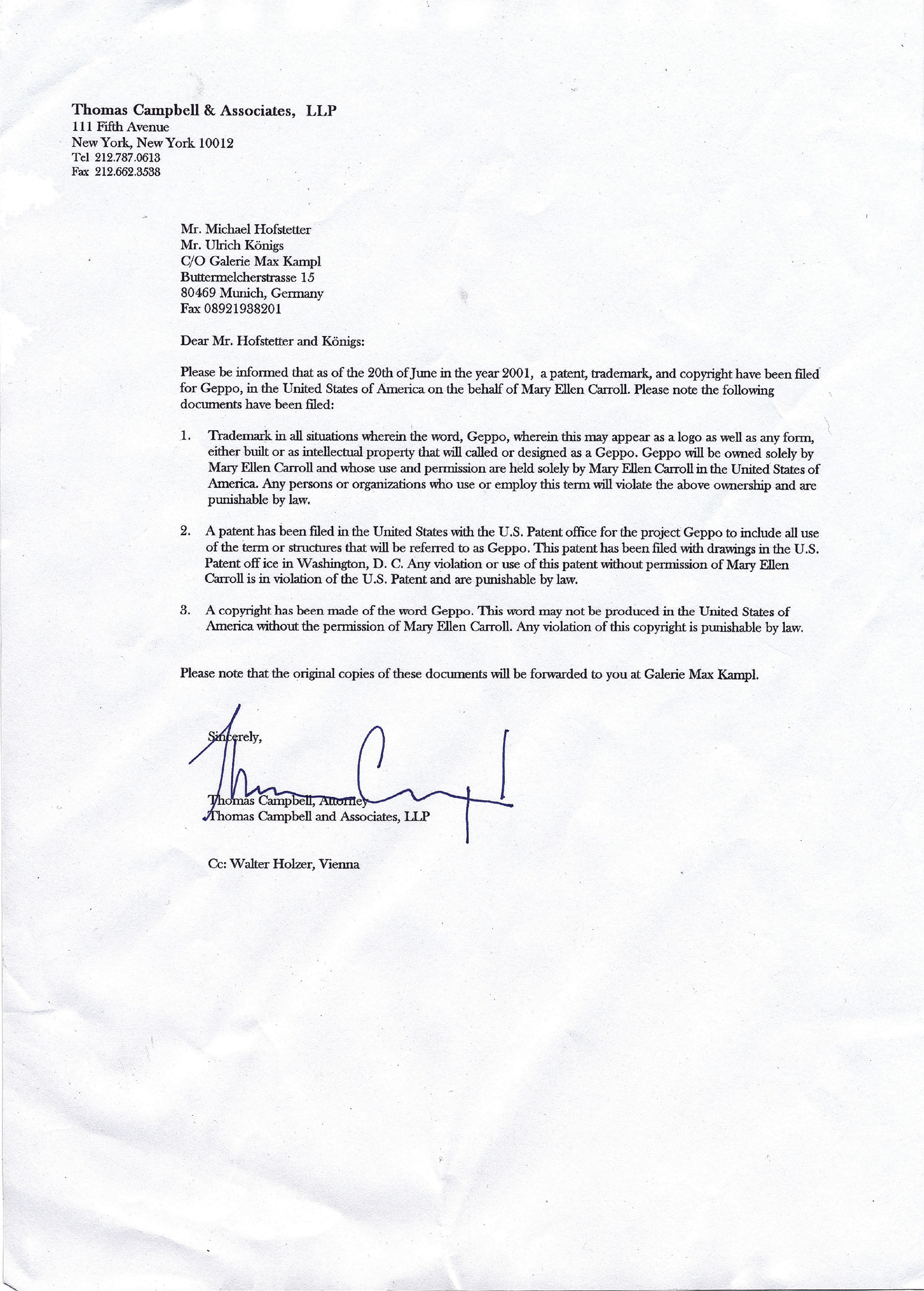

Hofstetter enlisted a group of artists to create a work that would utilize their model of a Geppo. A Geppo is a plan for a space that looks like architecture, but it has no specific use-value, or scale, and only exists in form; it is a line, a demarcation without specification. Carroll’s response to the invitation took the form of a letter. The letter was evidence of an action that was taken to obtain a trademark and patent for the Geppo, in America, in Carroll’s name. She would license or retain the rights in her country, America, and also proceeded to secure the rights in the rest of the world, excluding Germany.

It was pure tricksterism, ad infinitum. I asked Carroll about the attorney, the process of getting the trademark, the patent, the fees, and she said that she didn’t do any of it, that it was a hoax. Campbell is the nom de plume for her business affairs person, and that she initially contacted intellectual property attorneys after she wrote the letter to see about getting the trademark, but that most of them were so conventional in terms of their thinking about intellectual property that they didn’t get what she was trying to do, and what she was trying to do was also extremely expensive and that everyone thinks, and it is true, that America is an aggressively litigious place, so why not create a work that would resemble the course of action that would legitimately be taken within a capitalist system. Does it make it any less valid that it was a hoax when it is a conceptual work of art? Attorneys have an understanding of the law, but what they really have is a particular command of language, and that is what was threatening—the LANGUAGE.

The action or the interaction, the thing that takes the form to concept, is what is being isolated as the work of art, and Manfred and Mary Ellen could switch places, although they would need to switch materials, as Carroll too is a sculptor, but a sculptor of the social. When Carroll is utilizing the commercial system, the work has to take some form for the market, and this form resembles photography, film, video, performance, etc., but ultimately resides in language. Manfred makes us aware of ourselves or self-conscious through the observation and distillation of a work of art in relation to the actions that are taken to realize that work of art. Carroll makes us aware by the interaction between human beings and space, that space being in relation to another human being, or what would be construed as architecture, or even time—the place between two things where they exist as themselves. In writing this, I have repeatedly asked myself why Carroll just doesn’t write, what is the point of creating anything concrete at all if it is just a conceptual exercise, but then Carroll is writing.

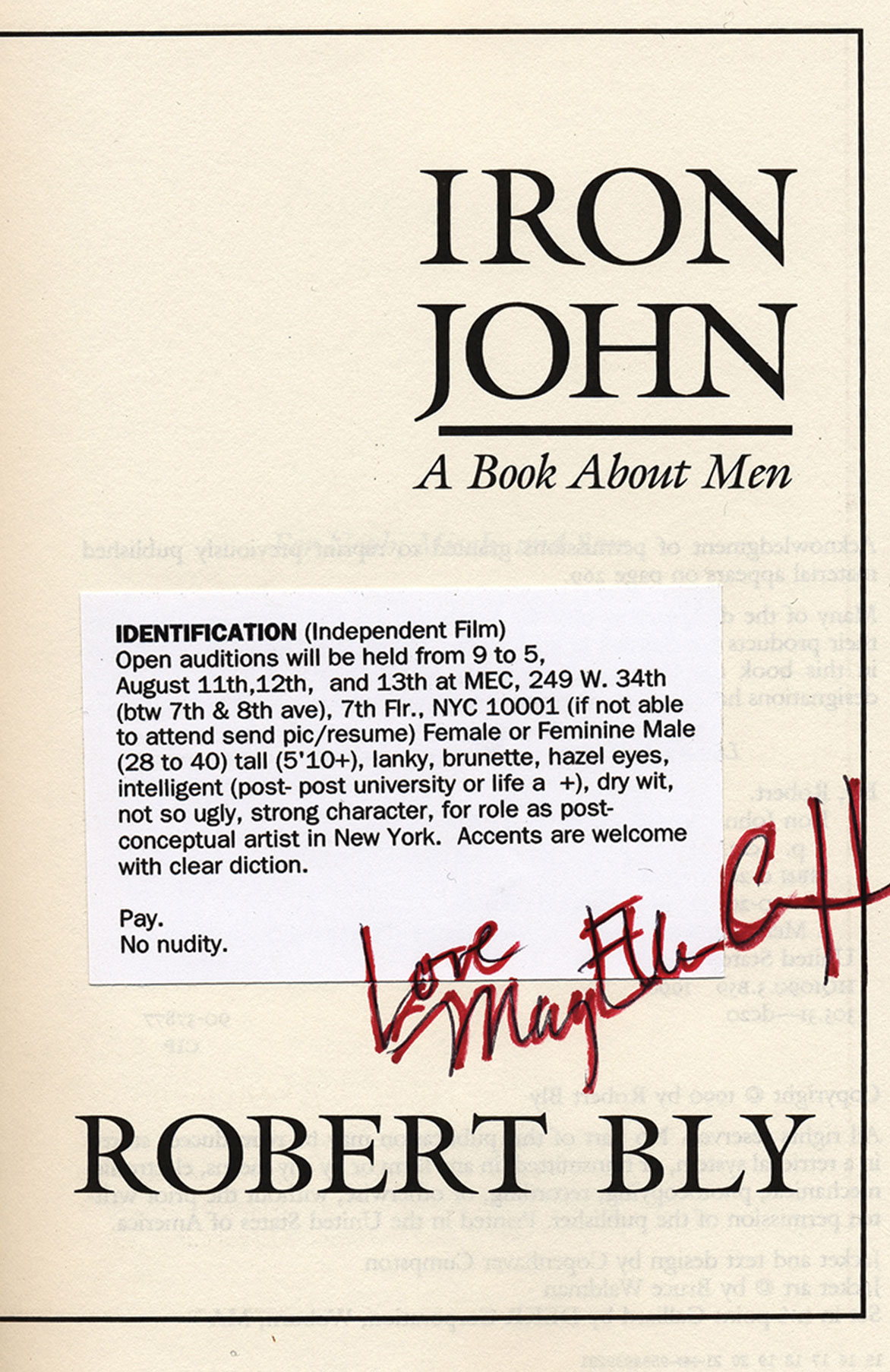

I opened my mail box today and there was another package from New York that contained a book. The book was Iron John, a book celebrating masculinity by the poet Robert Bly. I didn’t know if this was some part of Carroll’s process concerning my edification on her work, American culture, or my own masculinity. I opened this book and pasted in the interior was what looked like an ad, but where and if it had been placed, I didn’t know. It read like a casting call and was signed, “Love, Mary Ellen Carroll.”

It now makes sense why Carroll asked me to write this essay—a provocateur is also an astute observer.

Peter Herbstreuth’s name appears in this issue.