The Kingpin of Fakers

Colonel Dinshah P. Ghadiali and the Spectro-Chrome

Christopher Turner

Why is a tomato red and a cucumber green? Why does a raw green banana become yellow when ripe and not blue? Why does a brown cow eating green grass produce white milk, which when churned makes yellow butter?

—Dinshah Ghadiali

In an archive box at the National Library of Medicine in Washington, DC, crammed between a crushed can of ozonated olive oil (invented and marketed by Nikola Tesla) and folders on dubious vitamin supplements, are three files of evidence relating to the Food and Drug Administration’s investigation into a device called the Spectro-Chrome. An FDA agent who dismantled this curious machine, which looks like a simple aluminum slide projector mounted on a stand, described it as follows: “Examination showed that the device consisted essentially of a cabinet equipped with a 1000-watt floodlight bulb and electric fan, a container of water for cooling purposes, two glass condenser lenses for concentrating the light, and a number of glass slides of different colors.”

Colonel Dinshah P. Ghadiali, who invented the Spectro-Chrome in 1920, claimed to be able to cure almost everything with its twelve colors; after intensive treatment with “attuned color waves,” a badly burned infant now had satin-white silky skin, a blind girl’s sight had been restored, and a paralyzed woman was able to walk again. “The Spectro-Chrome is not a lamp,” Ghadiali asserted, “it is a system, a new, original and unique science.” By 1946, he had sold nearly eleven thousand devices, the most expensive of which cost $750, earning himself over one million dollars. “Many up-to-date homes are already equipped with a Spectro-Chrome just like the Electric Light, Telephone and Radio,” Ghadiali wrote, adding hopefully, “soon there will be a SPECTRO-CHROME IN EVERY HOME.”

The use of colored light in the treatment of illness and disease became fashionable in America in the late nineteenth century. While seeking a way to grow bigger grapes in his greenhouse in Philadelphia (the city where Ghadiali first established his Spectro-Chrome Institute), the retired general Augustus Pleasanton discovered that alternating panes of clear and blue glass was also the secret to restoring health. He published the results of these experiments in The Influence of the Blue Ray of the Sunlight (1876). Seth Pancoast extended this thinking in his Blue and Red Light: or, Light and its Rays as Medicine (1877), in which he cautioned against “light quacks” even as he claimed to have cured Master F., an eight-year-old paraplegic, after only a week under red glass, and Mrs. L., a thirty-two-year-old widow suffering from severe sciatica, after only three sittings in a bath of blue light.

The following year Edwin Babbitt, an American teacher and mesmerist, outlined his own, increasingly complex color theory in The Principles of Light and Color (1878). Babbitt believed that everyone radiated their own brightly colored energy and that sickness was visible to psychics as an upset in the natural harmony of this color field. He invented a device to restore equilibrium that he called the Chromolume, a stained-glass window composed of sixteen colors which sold for ten dollars. A less bulky five-dollar Chromo-Disk was marketed for easier “irradiations,” as well as a Chromo-Lens for charging drinking water with medicinal color. Scientific American dubbed the color healing craze the “blue glass mania” and offered the following prescription: “blue glass one part; faith, ten parts; mix thoroughly and stir well until all common sense evaporates, as the presence of a minute quantity will spoil the mixture.”

The mania for chromotherapy spread to Europe, where Charles Féré, a psychiatrist working under Charcot at the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, tinted the windows of hysterics’ cells with violet glass to create calming and curative effects. (Féré thought of colored light as different waves or vibrations of radiant energy which could be sensed not just by the eyes, but all over the skin in a form of cutaneous vision.) The fashion reached as far as India where Ghadiali, then working as the stage manager of a Bombay theater, read Babbitt’s treatise. He had his first opportunity to apply Babbitt’s principles of color therapy when a friend’s niece was dying of mucous colitis, which no ordinary medication seemed able to cure. He made a DIY Chromolume out of an empty purple pickle bottle and a powerful kerosene lamp borrowed from the Highway Department; he irradiated milk in a blue glass container which he also had her drink (the Spectro-Chrome stored five vials behind the bulb center in which water could be charged for this purpose). Within three days she was apparently totally cured and Ghadiali devoted the rest of his life to practicing what you might call medical showmanship.

Ghadiali emigrated to America in 1911 and set himself up as an inventor in New Jersey (near his hero Thomas Edison), where he began to elaborate on Babbitt’s theories, mixing them with Parsee philosophy, and updating the Chromolume for the era of electric light. Four years after he arrived, the New York Times reported that he had filed a patent for the Dinshah Photokinephone, which he claimed was the first film projector able to coordinate sound with flickering images without the use of a phonograph. The article claimed that he already had “several inventions to his name,” such as the “Dinshah Automobile Engine Fault-Finder.” The Spectro-Chrome, invented after a wartime stint as a pilot in the New York Police Air Reserves (where he rose to the rank of Colonel), promised to be even more miraculous. But how did it work?

In case Ghadiali’s device appeared to be too simple, he invented a labyrinthine language of his own to explain its occult workings. The therapists Ghadiali trained at the Spectro-Chrome Institute had to spend six hundred hours studying his convoluted three-volume instruction manual, The Spectro-Chrome Metry Encyclopedia (1933), as if clocking up the hours for a pilot’s license. To summarize his theory: Ghadiali believed that the body was made up of oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, and carbon, which were colored blue, red, green, and yellow respectively. When the four colors are out of balance, people become sick, and the Spectro-Chrome promised to restore a natural harmony. Ghadiali published a chart which showed the twenty-two parts of the body that particular colors should be projected onto to cure different illnesses, and specified the exact time of day each hour-long sitting should take place in a series of complicated regional astrological tables.

“Tonations” had to take place in a darkened room while the patient was naked, with eyes open and head facing north, so the body would be aligned with the earth’s magnetic fields. “Disorders with Growths or Tumours,” read a typical prescription, “developing slowly within the body, may be irradiated with Lemon Systemic and Indigo Local on the Affected Area, with Magenta on 4 [left breast] or 18 [middle back] where so indicated… For Excessive Sex Craving, irradiate with Lemon Systemic alternated with Purple on Area 11 [genitals].”

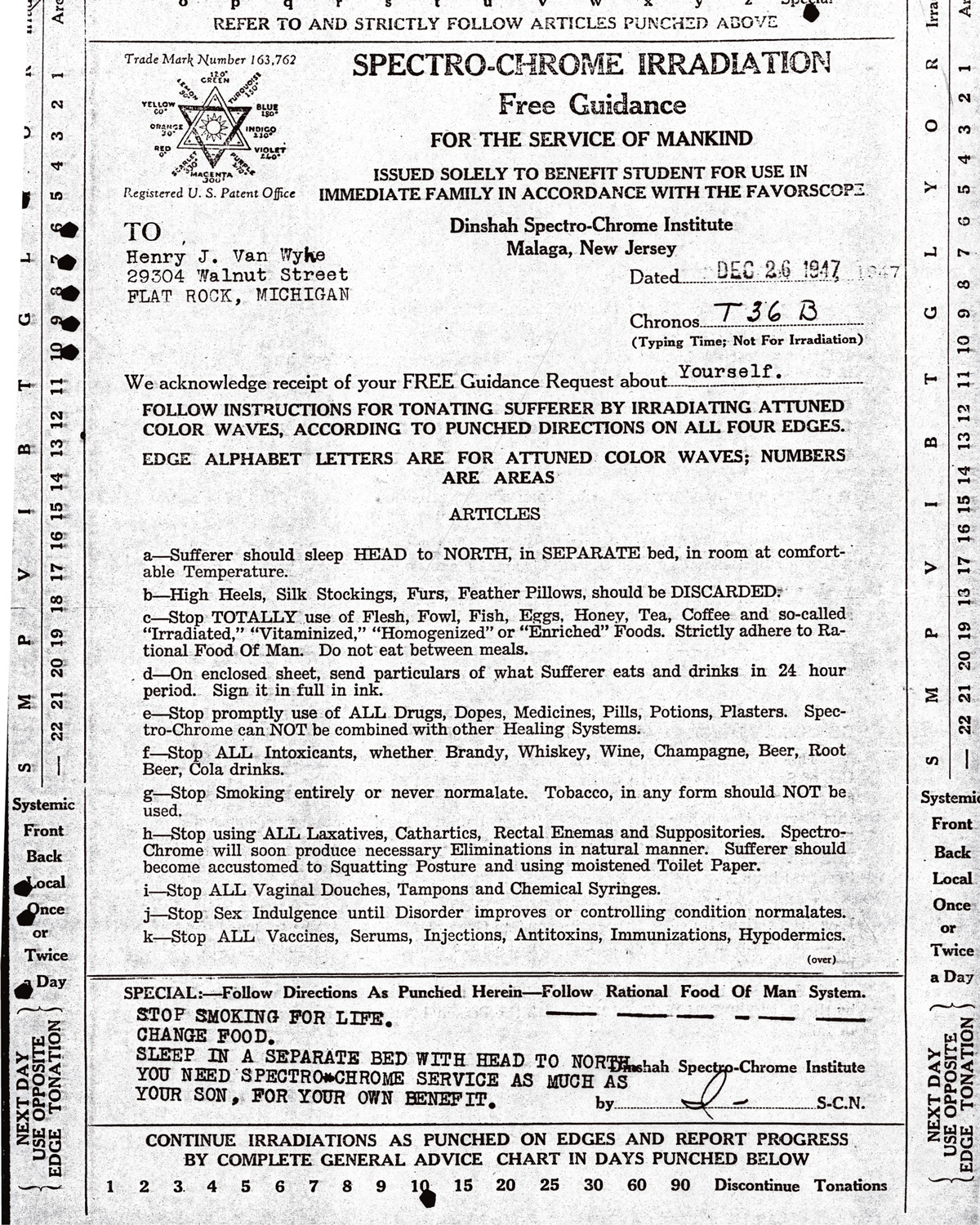

Spectro-Chrome Metry was more a cult than a health cure; members of the “Scientific Order of Spectro-Chrome Metrists” were encouraged to wear a special purple skullcap as a symbol of their allegiance. Patients, who came for rest-cures at the institute’s “Chromarium,” also had to adopt Ghadiali’s many prejudices: he was against high-heeled shoes, silk stockings, caffeine, tobacco, alcohol, drugs, pills, potions, furs, and enemas. Ghadiali persuaded them to assume his own eccentric habits if they were to get well; he practiced vegetarianism (and published his own cookbook of recipes), gargled with salt, bathed in coconut oil, cleaned his teeth after each meal (he sold a special toothpaste), and preferred squatting over a hole to using a lavatory. When people wrote to him seeking a cure to their ailments, they were returned a “Free Guidance Chart”—instructing them as to what colors to project where and when—which listed all these peculiar rules along with some personalized instructions. One man—who was, in fact, an FDA agent—wrote in to describe his sick son’s symptoms, only to receive unsolicited advice for himself:

“THE SUFFERER MUST: CHANGE FOOD. SLEEP WITH HIS HEAD TO THE NORTH, THIS CASE WILL NEED CAREFUL WATCHING.

YOU STOP SMOKING FOR LIFE. CHANGE FOOD. SLEEP IN A SEPARATE BED WITH HEAD TO NORTH. YOU NEED SPECTRO-CHROME SERVICE AS MUCH AS YOUR SON, FOR YOUR OWN BENEFIT.”

Ghadiali’s slogan was, “No Diagnosis, No Drugs, No Surgery.” “Stop Insulin at once,” he advised diabetics, “and irradiate yourself with Yellow Systemic alternated with Magenta on Areas 4 or 18 and eat plenty of Raw or Brown Sugar and all the Starches!!!.” These kinds of prescriptions were to make his run-in with the medical establishment inevitable. Ghadiali had never received any medical training, though he would often appear in full military regalia in the advertising material he used to promote the Spectro-Chrome as Colonel Dinshah P. Ghadiali (Honorary) M.D., M.E., D.C., Ph.D., LL.D., N.D., D.Opt., F.F.S., D.H.T., D.M.T., D.S.T. All of these qualifications, save the ones he awarded himself as president of the Spectro-Chrome Institute, were bought from diploma mills; his M.D., for example was bought for $133.33 from Oskaloose College, a diploma mill in Iowa. He wanted to be a doctor and disguised his jealous hatred of them by claiming that it was in fact the medical profession who felt envious and threatened by his cure-all. He published a cartoon of the “Medical Octopus” straddling the “Ocean of Ignorance” and the “Bay of Bunk,” each tentacle a different medical institution. “This fearful-looking monster is the dread of America,” he wrote, “but, the TRUTH behind the Scientific Researches of DINSHAH makes it squirm in agony. It dares not A PUBLIC DEBATE, because, Dinshah WILL pound it into pulp.”

In 1931, Ghadiali was arrested in Buffalo for second-degree grand larceny after someone who had bought a Spectro-Chrome complained to officials that it did not perform as promised. Ghadiali persuaded three surgeons to testify in his defense. Dr. Kate Baldwin, Senior Surgeon at the Women’s Hospital of Philadelphia, claimed that she had successfully treated glaucoma, tuberculosis, cancer, syphilis, gastric ulcers, and serious burns with the Spectro-Chrome. “I am perfectly honest in saying,” she told the court, “that, after nearly thirty-seven years of active hospital and private practice in medicine and surgery, I can produce quicker and more accurate results with colors than with any or all other methods combined—and with less strain on the patient.” As a result of such testimony, Ghadiali was acquitted (he’d already spent eighteen months in jail in 1925, accused of having sex with his secretary, who was underage, though he maintained he’d been framed by the Ku Klux Klan). The American Medical Association, feeling that the government’s expert witnesses had been humiliated in the trial, began their own investigations. They concluded in 1935 that the Spectro-Chrome, which they described as “a cross between a stereopticon and an automobile heater,” was worthless. Ghadiali’s machine, they wrote, was reminiscent “of the marvelous gadgets illustrated by cartoonist [Rube] Goldberg,” which achieve minimal results with maximum effort.

After the passage of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938, which granted the FDA new powers in regulating therapeutic devices, the government once again began to assemble evidence against Ghadiali. The Spectro-Chrome was only one of the devices on the market for localized color therapy—by 1938 you could buy the Emesay, Kromayer, Alpine Sun, Helion, and Chromoclast lamps, all kitted out with localizing masks and color filters for chromotherapy—but it was singled out for special investigation. FDA agents tracked down newspaper advertisements placed by people selling secondhand Spectro-Chromes, in order to try and identify dissatisfied customers. Agents posed as patients; doctors conducted independent trials. The post office provided the addresses of every Spectro-Chrome consignee, whom FDA agents then visited and interviewed (their names, collected in the McCarthy era, read something like a blacklist: Walter Chandler, Anna Cabaj, Dorothy Westphol, Stella Hitkowosk).

Finally, in October 1946, Ghadiali appeared in court charged with introducing a misbranded article into interstate commerce, a violation of the criminal code. “The use of colored lights would have no effect on health,” the FDA concluded, “and when used as directed, or in any manner whatsoever, may delay appropriate treatment of serious diseases, resulting in serious or permanent injury or death to the user.” Lawyers for the prosecution called seventy-six witnesses, including several of the experts in diabetes, heart disease, tuberculosis and cancer from whom they’d commissioned independent clinical trials and animal tests. They had found the Spectro-Chrome to be “of no value at all in any of their specialties.” Any cures that had been made were attributed to auto-suggestion or to the diseases and fevers having run their natural course.

The government attacked five of the case histories in Ghadiali’s Encyclopedia in particular, proving that his claims to have cured these patients were false—three had in fact died from their conditions. The burn victim Dr. Kate Baldwin claimed to have healed died a few months after leaving the hospital, her body one open sore. A blind girl who supposedly had had her sight restored by Spectro-Chrome Metry was still blind and always had been. The paralytic, treated from age three to seven with the machine and photographed in the book to prove she was able to walk after her color therapy, was pushed to the witness box in a wheel chair. She explained that she had been held upright until the camera was focused, wobbled for a fraction of a second while a picture was snapped, and was caught as she tumbled to the floor.

Ghadiali called 112 satisfied Spectro-Chrome users in his defense (fifty-seven of whom merely suffered from constipation) and the trial lasted two months as a result. Some of them had become quite dependent on their machines—one woman claimed she patted and talked to hers. But Ghadiali’s case effectively crumbled when a patient he claimed to have cured of epilepsy with “tonations of Orange Systemic,” went into seizures on the stand, slumped to the floor, vomited, and swallowed his tongue. A real doctor rushed over to him and stopped him from choking to death by holding his tongue down with a pencil. “The jury was sent out and the court was recessed,” read the FDA’s notes on the trial, “Dinshah P. Ghadiali stood coldly by and neglected to offer Spectro-Chrome treatment.” After seven and a half hours’ deliberation, the jury returned to declare Ghadiali guilty. His dream of having a “SPECTRO-CHROME IN EVERY HOME” ended when he was given a three-year prison sentence and fined $20,000; all his promotional literature was ordered to be burnt, and further production of Spectro-Chromes outlawed.

On his release in 1953, Ghadiali simply changed the name of his organization to the Visible Spectrum Research Institute; in 1958, the FDA obtained a permanent injunction through a federal judge and closed him down. He died in 1966, aged ninety-two. His son, Darius Ghadiali, is now seventy-seven and runs the latest incarnation of the Spectro-Chrome Institute, the Dinshah Health Society, still based in Malaga, New Jersey. He sells his father’s books and pamphlets, but not his devices (the injunction still stands); however, he has published “Inexpensive Projector Plans” in his book Let There Be Light (1985), illustrating how to build a makeshift Spectro-Chrome out of cardboard, theatrical filters, and a reflector lamp: “Tonate with confidence,” Darius Ghadiali writes, “using a 25 or 40 watt bulb” (after all, his father started out with a kerosene lamp and a pickle bottle).

During a recent telephone conversation, Darius Ghadiali described his father to me as “stoic, charismatic, short-tempered, autocratic,” and told me that he was known as the “Kingpin of Fakers” because of the million dollars he made. “My father did tend to not necessarily quite stick to facts,” he admitted, “he was a little bit flowery, which in the 1931 Buffalo case—the only major case he won—the judge called ‘puffery,’ but he also said that that in itself did not make fraud.” The institute made five hundred Spectro-Chromes a year in its heyday, and Darius and his six brothers spent their childhood casting, assembling, and painting boxes. Though their father made a fortune selling Spectro-Chromes, he died fourteen thousand dollars in debt. “It was made and spent,” Darius explained, “on development, lectures, advertising, building, lawyers; very little for personal use—we lived on shoe strings almost.”

The Society now boasts three to four thousand members, many of whom meet in Malaga for an annual conference. Darius Ghadiali considers himself to be living proof of his father’s theories: he has only taken antibiotics once in his life, and told me that his current regimen includes drinking water charged with Lemon Systemic. “The time for universal use of the Spectro-Chrome has not yet arrived, but it will come eventually,” he concluded optimistically. “It has to: the Spectro-Chrome is just too useful. There is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come.”

Christopher Turner is an editor at Cabinet and is currently writing a book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came to America to be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.