Breakfast

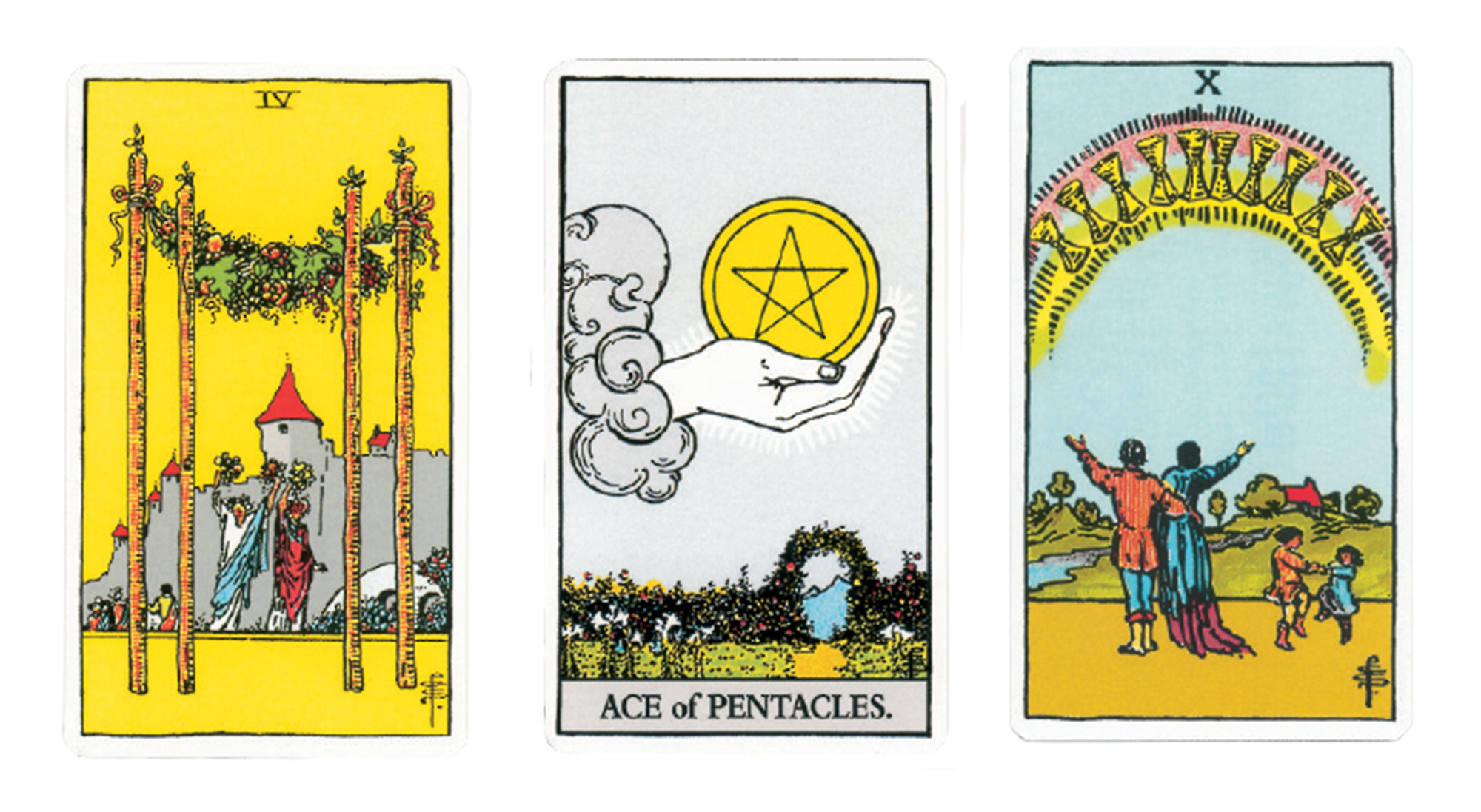

Temperance, The Star, The Hanged Man, Four of Wands, Ace of Pentacles, Ten of Cups

Francine Prose

The images of the tarot deck are supposed to buzz through your brain, forging new neural pathways, making speedy end-runs around language, culture, experience, and whether or not you have any idea what the cards mean. The beauty of the Waite deck is you do know what they mean. A guy lying on his face with ten swords sticking out of his back like toothpicks on an hors d’oeuvres tray probably means what you think. Which is why they are frightening even for the unsuperstitious. Everyone knows the Death card is lurking in there, waiting. You don’t have to believe in the predictive powers of a deck of cards. Everyone believes in the armored skeleton on horseback.

Laying out the cards, I find myself dealing oddly, from left to right, as if some part of me truly believes that I am involved in a voodoo event. To tell the truth, it’s a bit of a horror-movie moment, like the scene in The Hands of Orlac in which the injured pianist with the transplanted killer’s hands suddenly realizes he’s got murderers at the end of his wrists.

The tarot, and the operations of chance, should inspire intuition, quick readings burbling up from the fountain of the unconscious, or from one of those newly discovered kinds of subcerebral intelligence. And this experiment, as I understand it, is meant to involve the fictive imagination, the power of the images to inspire narrative. Each card should have been a bead to string on that cord that runs through a story.

But the the six cards I have dealt mean nothing to me. Nothing. No narrative, no mirror.

It doesn’t take a serious student of the tarot to figure out that these cards are the tarot equivalent of the three cherries coming up on the slot machine. You don’t need to know that the ace of pentacles means money, that the hanged man is the most problematic image, but that may just signify indecision or transition. As tarot readings go, this one is heaven. Pure vanilla.

I have dealt a TV ad for a breakfast cereal.

Perhaps I should explain that recently there has been a death in our family, so that if the Death card had turned up, it would have simply seemed like reportage. All these trees and flowers and fruit, blues skies and happy dancing children could not have less to do with my current state of mind, nor can I imagine generating a story from a series of images that have no conflict, no variation, no nuance. No event.

Maybe the problem is that I didn’t leave enough to chance, or left the wrong things to chance. Perhaps I started at the wrong point. Perhaps the taxi-meter of chance began ticking earlier, not when I dealt the six cards, but when I first took the deck out of the box. The first card I saw was the Tower, the lightning-struck Tower, which describes my psyche at the moment better than the pre-Raphaelite Disneyland of the cards I have actually dealt.

I dealt the three from the Major Arcana first, but was my major-before-minor decision a matter of chance, or of some status-conscious preconditioning? And then there is this: the deck arrived already separated into the Major and Minor Arcana, but still I had to look for the place where the break was divided. As I flipped through the deck, it seemed to me that chance was flinging certain cards out at me. The Moon with its the howling dogs and the lobsterlike creature crawling up out of the sea. The lightning-struck Tower and the Moon. That could have led into a story. But that isn’t my story, the one inspired by chance. I was playing by the rules, but what are the rules of chance? And what exactly does the chaos of chance have to do with the logical order of science?

As the six cards turn up in front of me, there’s no spark to set off that chain reaction that sets a story in motion. I leave the room and return. Still nothing. I leave them out on my desk. I’ll let them sit there as long as it takes, until they reveal what they mean.

The next morning, my husband makes breakfast: the first blossoms from the zucchini plant in the garden, deep fried in batter, and fried eggs from the chickens that we only recently got, so that the eggs are still an occasion.

I look at the glowing food, radiant in the sunlight.

I realize that the tarot cards have predicted breakfast: the zucchini blossom and the sunny-side-up egg. I’ve never thought of the tarot that way, as a sort of menu.

I had thought the word breakfast. Or actually, breakfast cereal. But I’d gotten it wrong, imagining that Waite deck must mean some sort of granola or possibly some pink and hideous British breakfast sausage.

I also realize, only now, how rural and springlike is the image that the six cards combine to form. The iris on the Temperance card is blooming outside at this very moment, and is that one of our chickens in the tree below the Star? Was it sheer chance that the tarot deck intuited that I am in the country, and that it is mid-June?

This is what the experiment has left me wondering about chance: Was it chance, or something else, that allowed the six cards to predict the next day’s breakfast? And was it chance, or something else, that this breezy, lightweight, limited prognostication is the heaviest message from destiny that I could have borne, or can bear, at the moment?

Francine Prose’s most recent novel is A Changed Man (HarperCollins, 2005). A brief biography of Caravaggio will be published in the Eminent Lives series in October, and a book on reading, Reading Like a Writer, will appear in fall, 2006.