Extraordinary Voyages

The first daredevils of Niagara Falls

Christopher Turner

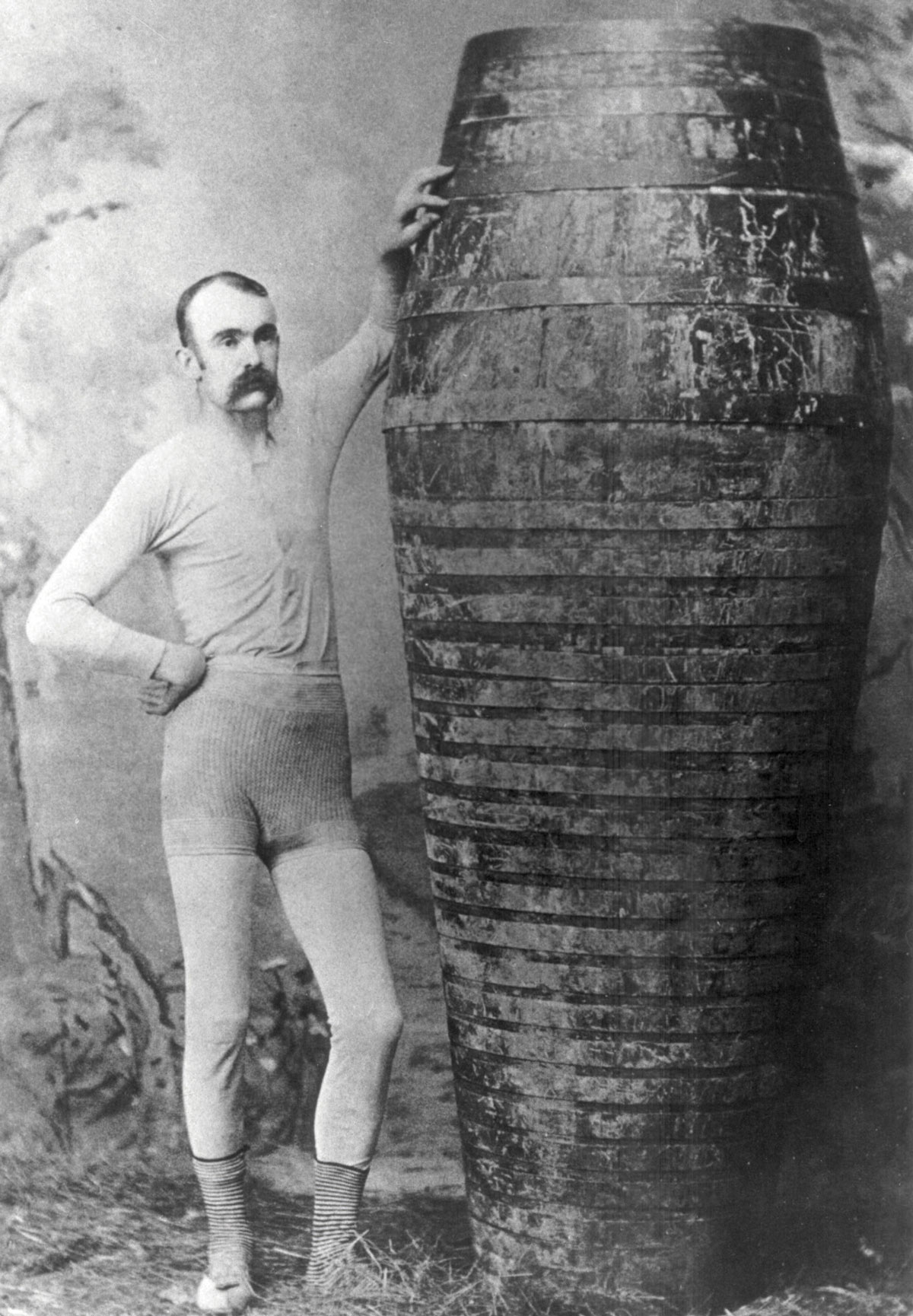

Carlisle Graham, a cooper from Philadelphia, was the first person to dream up the crazy idea of going over Niagara Falls in a barrel. Above is a photo of the Victorian daredevil, wearing tights and sporting a huge black moustache, posing by the seven-foot-tall cask in which he hoped to perform the impossible feat. He’d built the barrel himself, and it was painted bright red like a little makeshift rocket. Resembling the hero of one of Jules Verne’s “Extraordinary Voyages,” Graham looks ready to be fired by a cannon to the moon, or to be sucked through an abyss into the center of the earth.

In 1886, Graham catapulted to fame when he rode the treacherous Whirlpool Rapids in the gorge below the Falls in his oak barrel. His stunt made the front page of the New York Times, which described his craft as looking like “an enormous carrot.” He strapped himself into it with canvas suspenders, the lid was screwed on, and he clung to iron handles as it spun like a top through more than two miles of ferocious boilers and eddies. Graham entertained crowds four times by making this run, which many died copying, before upping the ante and promising to go over the Falls.

One morning on September 1889, the “Hero of Whirlpool Rapids” stumbled into one of Niagara’s saloons, wet and exhausted, with tales of having done just that. Despite seemingly hopeless odds, he claimed to have thrown himself into the waterfall like a ball-bearing into a churning roulette wheel and beaten the house. “I felt like a man who has passed into the painless portion of death by drowning,” Graham recounted as he revived himself with whisky, “There was a terrible roar in my ears. I tried to speak aloud in the barrel to break it, but I couldn’t… I felt a contented resignation.”

A few days later, investigative reporters from the Buffalo Evening News exposed Graham’s story of cheating death as an elaborate hoax; his braggadocio, they wrote, was merely “corroborative detail intended to give artistic verisimilitude to a bold and unconvincing narrative.” Though he had set the dare, Graham could only fantasize about risking it. He knew it was a suicidal journey—a month earlier he had sacrificed a Newfoundland dog to the Falls; the dog drowned when the barrel it was strapped into splintered in the mad rush of water.

But his challenge, which became the paragon of daredevilry, proved irresistible to the Victorian imagination (that same month Stephen Brodie, a newsboy from New York who claimed to have jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge, pretended to have gone over the Falls in an inflatable rubber suit), a world in which showmanship and mad stunts were continually being upstaged. The French funambulist, Emile Blondin, for example, began his series of apparently effortless “ascensions” over Niagara Falls in 1859, each trip more spectacular than the last: he carried his manager over the river on his back; he wore an ape costume to push a wheelbarrow across the high wire; and, as if to mock the overpowering Falls with domesticity, he erected a small stove half-way over and cooked two omelets which he lowered down to openmouthed onlookers on the sightseeing boat, Maid of the Mist.

By 1900, Niagara Falls was known as “Suicide’s Paradise,” because no one survived the drop—to do so would be almost to reverse the natural flow of the river itself. The ceaseless roar of water over the Falls seemed to symbolize the inevitability of death: “Down this predestined course,” wrote a nineteenth-century visitor, “ton follows ton as remorselessly as human generations speed to the great Unknown.” Kant had described the feelings conjured up by the sublime as a giddy “vibration…a rapidly alternating repulsion and attraction,” and many of Niagara’s visitors succumbed to this vertiginous draw. Harriet Beecher Stowe became so “maddened” by the Falls’ dynamic beauty that she imagined that hurling oneself into the cascade, as so many had done, would be a “beautiful” death.

• • •

On October 24th, 1901, Annie Edson Taylor became the first human being to truly attempt the treacherous trip over Niagara Falls in a barrel. Taylor, a plump former dance teacher from Auburn, New York, was an unlikely daredevil—she turned sixty-three that day (though she claimed to be forty-four) and was unemployed and destitute, too proud to face life in the poorhouse. “I might as well be dead, as to remain in my present position,” she said. Her stunt would be a life-or-death test and had a desperate, but rational, economic logic: If she died, as everyone expected she would, her unhappiness would be over; if she lived, she would emerge from the cascade showered with riches.

Taylor engaged a manager who represented high-divers in carnival acts to choreograph this anticipated change in fortune and she had a four-and-a-half foot barrel especially built for the stunt. It was equipped with a harness, packed with pillows and had a 200-pound anvil for ballast. “I will not say goodbye,” she said before she was sealed into the coffin-like darkness, “but au revoir, because I’m coming back.” No one believed her—Maude Willard had suffocated to death in the Whirlpool Rapids the previous month in one of Graham’s barrels—and numerous photographs show onlookers crowding around the cask as though it were a gallows. “The easiest way to attract a crowd,” Houdini later wrote of his own brand of sub-aquatic escapology, “is to let them know that at a given time and a given place someone is going to attempt something that in the event of failure will mean sudden death.”

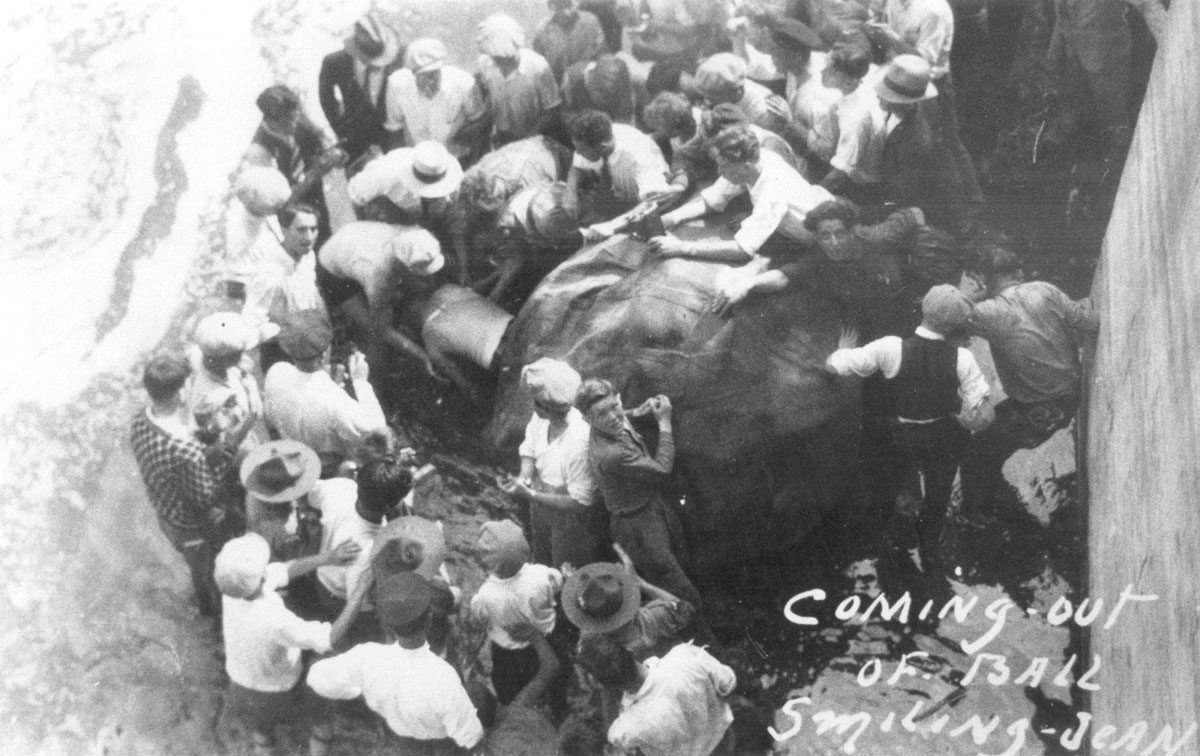

Taylor’s barrel was released in smooth water upstream, before bobbing through the rapids, which were, in her description, “like a thing of life, fighting for its prey.” The waterfall, which gushes 150,000 gallons of water per second, spat her into the 150-foot plunge pool at its base, and she disappeared from sight. The barrel spun around, she said, “like butter in a churn,” momentarily caught in the Falls’ lethal cross-currents, before bobbing back to the surface and fifteen feet into the air. Carlisle Graham helped to fish her out; when he prized off the lid of the barrel, he exclaimed with genuine surprise, “Good god! She’s alive!”

Taylor had a three-inch gash in her head and was obviously concussed. She kept asking, “Have I been over the Falls yet?” When she recovered she told reporters, “If it was my dying breath, I would caution anyone against attempting the feat. I will never go over the Falls again. I would sooner walk up to the mouth of a cannon, knowing it was going to blow me to pieces, than make another trip over the Falls.”

She earned fame, but not fortune. Her manager ran off with her precious barrel and sold it to a theatre in Chicago that was staging a play based on her exploits. Taylor hired a lawyer to reclaim it, and the lawsuit consumed what little money she had earned lecturing about her adventure. It was ten years before anyone else would be brave enough to attempt the barrel ride, but in the decade of her monopoly Taylor proved too dour and serious for the hyperbolic world of sideshows. The “Heroine of Horseshoe Falls,” as Taylor styled herself, died in poverty, having eked out a meager living by allowing tourists to have themselves photographed alongside her with a replica barrel; her grave doesn’t record the date of her death or birth—only of her stunt.

In 1911, Bobby Leach, a circus stuntman from England—who had already parachuted off Niagara’s Upper Suspension Bridge and been down the Whirlpool Rapids in a barrel—successfully went over the Falls and assumed Taylor’s crown. Leach’s vessel was an eight-foot-long cigar-shaped contraption made of steel. Like Graham’s barrel, it was painted bright red and looked like the rocket that hits the moon squarely in the eye in Georges Melies’s film, Voyage dans la Lune. (The film came out the year after Taylor’s stunt.) Leach hung inside it—blind drunk—in a waterproof canvas hammock, but he was badly injured when his craft struck a rock just before it dropped down the chasm. You can see the dent it made in Leach’s contrivance—there is a photograph of him sitting on it; as a result he spent twenty-three weeks in hospital with shattered knee caps and a broken jaw. Obituary writers delighted in the daredevil’s prosaic end: he died many years later at the age of seventy, after slipping on a piece of orange peel.

Leach felt that it was the tough shell of riveted steel that had saved him, and nine years later, when Charles Stephens planned to go over the Falls in a wooden barrel, Leach tried to dissuade him. Stephens, a fifty-eight-year-old English barber (the challenge was attracting daredevils the world over), built himself a six-foot-long barrel of Russian oak which was the most high-tech and fantastical device to date; a cross-section shows him harnessed inside it, sucking on the tube of an emergency air supply. His barrel even had electric light to alleviate the claustrophobic darkness. However, when it cleared the foaming sheet of water and hit the base of the falls, the anvil that he tied to his legs as ballast is presumed to have kept going, breaking through the bottom and taking Stephens with it—he became the first of the barrel stunters to die going over the cataract. Only his arm, which had been severed by the harness, ever resurfaced. Along with the broken staves, the limb floated downstream carrying a tattooed message: “Forget me not, Annie.”

Despite this eerie warning, adrenalin junkies, addicts of the sublime, continued to dare the devil, or to succumb to the devil’s dare. In 1928, Jean Lussier from Canada rolled down the rapids and over the brink of the Falls in a reinforced 760-pound rubber ball, which he’d spent his life’s savings building, and became the third person to make it over alive. Two years later George Stathakis, a chef from Buffalo, made the attempt in a bulky 2,000-pound barrel, but was trapped in the vortex of water beneath the Falls for more than fourteen hours and suffocated to death (though the tortoise he took with him for good luck survived). In 1951, William “Red” Hill Jr. went over the waterfall in a flimsy craft made of thirteen heavy-duty inner tubes which he christened “The Thing,” after the movie of that year, and became the third victim of barrel-riding daredevilry.

So, on the fiftieth anniversary of Annie Taylor’s inaugural feat, three people had died and three had survived. Your odds of making it over the Falls in a barrel, in this Russian roulette of a sport, were fifty-fifty, heads or tails, life or death.

• • •

Hill’s death provoked a public outcry—many thought that daredevils merely legitimized and romanticized suicide—and there is now a law against going over the Falls, referred to as “stunting without a license.” Needless to say, no licenses have been issued since. However, the ban did not put an end to stunts. In fact it seemed to improve them—the daredevils’ vehicles became increasingly sophisticated, more like submarines or space pods than pickle barrels. With sturdy and buoyant frames, interior padding, jump seats, harnesses and oxygen tanks, they sealed the passenger into a self-sufficient womb-like space. Since the ban was imposed, no one has died going over the Falls in a barrel, and of the thirteen people who have deliberately taken the plunge in reinforced drums, two have made the trip twice.[1]

In 2003, Kirk Jones, a forty-year-old unemployed man from Michigan, became the first person to survive going over the Falls without any safety device at all, effectively ending the era of barrel riding. One of Niagara’s surviving daredevils complained that Jones’s failed suicide attempt “cheapened the legend.” Jones steeled himself with two liters of vodka and orange and floated towards the crest of the Falls on his back. He had, according to one witness, a smile on his face, and went over the roaring cascade headfirst. His brother was with him and was supposed to videotape it, but the battery died.

- However, Karel Soucek, who went over the Falls in 1984, died recreating the stunt in the Houston Aerodome when he was dropped 180 feet into a tank of water in front of 45,000 people. His barrel cracked like an egg on the lip of the ten-foot wide tub.

Christopher Turner is an editor at Cabinet and is currently writing a book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came to America to be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.