Psychoanalytic Filiations

A Freudian family tree for your wall

(accompanied by a poster insert)

Ernst Falzeder

In psychoanalysis, the borders between professional training and personal relationships are much less distinct than its proponents want us to believe. Through the personal analysis of the analyst-to-be, each psychoanalyst becomes part of a genealogy that ultimately goes back to Sigmund Freud and a handful of early pioneers. There exists, in other words, an invisible psychoanalytic “family tree.” Wouldn’t it be interesting to draw it up?

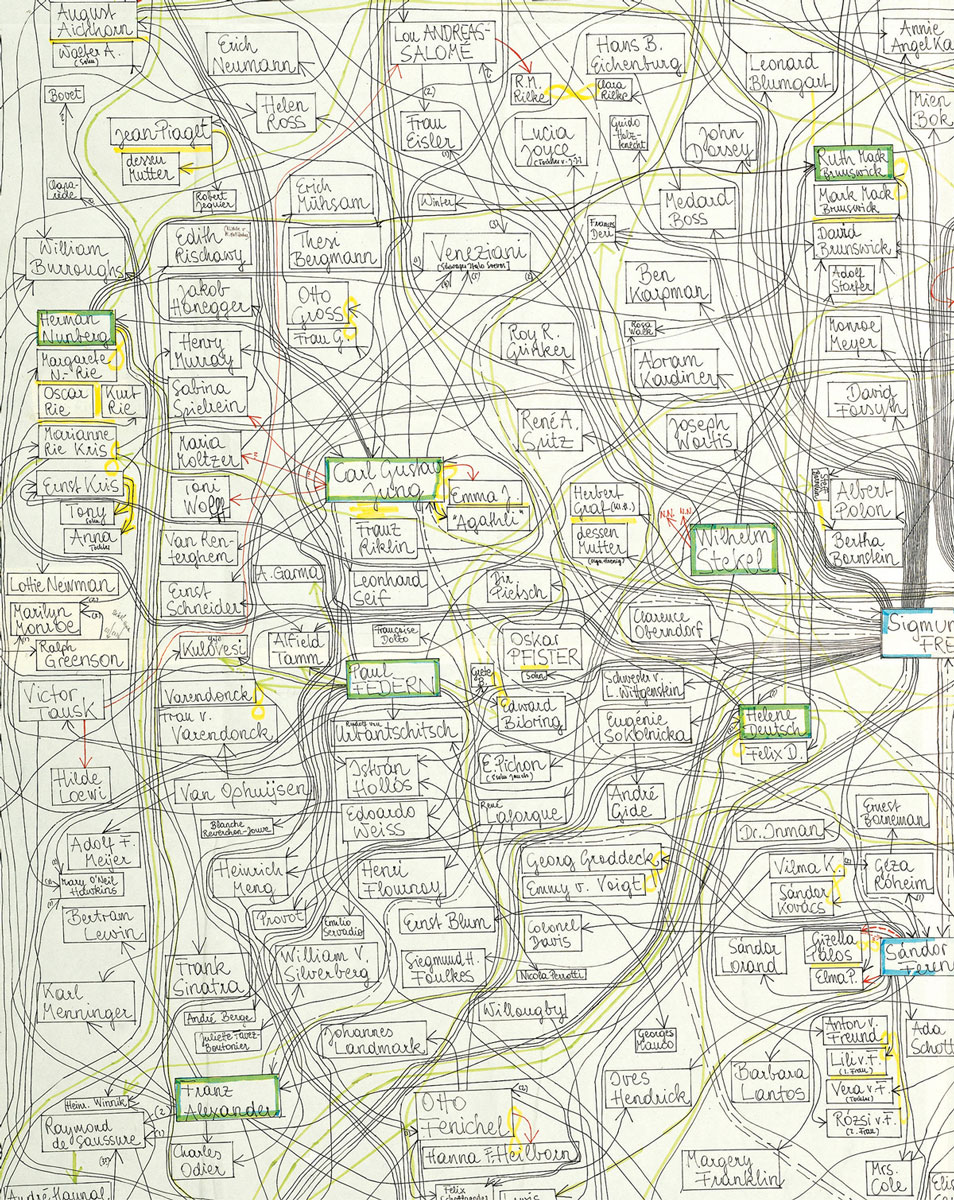

Well, I started. At first, I limited myself to prominent analysts of the period until the 1930s, thinking it might be useful as an informal source of reference for my historical work. It was fun to see a map of psychoanalytic filiations develop on the wall in my study. I put a big sheet of paper there, and whenever I came across information in the literature, in archives, or in interviews on who analyzed whom, I joined them with an arrow. (Black for simple analysis, double-headed for mutual analysis, yellow for analysis with relatives, green for supervision, red for analysis plus erotic relationship. Names of unanalyzed analysts are capitalized.)

Clusters, patterns, centers of influence, and unexpected connections became visible; nodes, crossroads, and bridges materialized; lines of thought and influence could be traced through this “spaghetti junction.” The resulting chart was by no means exhaustive, but a couple of facts soon emerged. This was no ordinary family tree: analysands had up to five analytical “fathers” or “mothers,” they had repeat analyses with the same parent, they reversed roles by analyzing their parent(s) later on, and they even analyzed each other simultaneously. Much to my chagrin, no genealogical software known to me could handle this web of associations; what came closest, according to two software experts I asked, were either a program for electric circuits or one used by airlines for their flight schedules, which made me free associate about blown fuses and Fear of Flying.

This network pervaded all aspects of the lives of those involved, making border violations in every conceivable area the rule and not the exception. Analysts slept with their patients, spouses and lovers analyzed each other or shared an analyst. There has been much discussion about whether Freud had an affair with his sister-in-law Minna Bernays, but what is perhaps even more startling is the idea, brought forward by Lisa Appignanesi and John Forrester, that he might have analyzed her. Sigmund Freud did not only analyze Marie Bonaparte and her lovers Heinz Hartmann and Rudolph Loewenstein (who himself analyzed Bonaparte), but also her daughter Eugénie; her son Pierre was analyzed by Heinz Hartmann. Erich Fromm analyzed Karen Horney’s daughter Marianne, while having a relationship with Horney. As a child, Marianne, as well as her sister Renate, had already been analyzed by Melanie Klein. Brigitte, the third daughter, who was to become a well-known actress, should also have been treated by Klein, but, being fourteen years old and strong-willed, she refused to go for analysis at all.

Parents analyzed their own children as well as the children of their lovers. In 1925, Lou Andreas-Salomé remarked to Bloomsbury analyst Alix Strachey that “parents were the only proper people to analyze the child.” When Alix reported this to her husband James, she added: “A shudder ran down my spine.” Anna Freud’s analysis with her father is obviously the most famous example. (Franz Alexander, who had perhaps had some form of training with Freud himself, analyzed Freud’s son Oliver.) But Freud was not the only one to analyze one of his children: Karl Abraham treated his own daughter, Hilda; Carl Gustav Jung his daughter, Agathli; Ernst Kris his two children, Anna and Tony. Melanie Klein analyzed all of her children. Aunts also analysed their nephews: Anna Freud’s first patients were two of her nephews, “Heinerle” Halberstadt and Ernst Halberstadt. Hermine Hug-Hellmuth also analyzed her nephew; he later strangled her to death (in his trial, he described himself as a victim of psychoanalysis).

This psychoanalytic “horde” was indeed a “wild” one, to take up Freud’s expression, and the following generations made strong, although not always successful, efforts to civilize it by structured training, strict guidelines, ethics committees, etc.

But apart from the fun, and a touch of voyeurism, in delving into this story, is there anything more to it? I only began to understand the significance of my leisure pursuit when I realized that there was a discrepancy—with only a few exceptions—between how this sort of information was being treated in print, and how it was dealt with in personal letters, memoirs, or informal exchanges. In publications, if psychoanalytic filiations were discussed at all, it was only in passing, as if adding just a little insider gossip or background information. In the profession, however, these therapeutic links were considered to be of paramount importance. Depending on the local orthodoxy, a low “Freud factor,” or “Melanie Klein factor,” etc., could be decisive for one’s career. The famous developmental psychologist, Jean Piaget, even falsely claimed that his analyst, Sabina Spielrein, had herself been analyzed by Freud, in order to ennoble his analytic family romance by making him a direct “grandson” of Freud.[1] (Piaget, by the way, also analyzed his mother. A failure, not surprisingly.)

Half a century after the beginning of what Freud called the psychoanalytic movement, one of its more iconoclastic members, Michael Balint, called attention to the resemblance between the analytic training system, primitive initiation ceremonies, and what he termed “apostolic succession.” While the members of the first generation of analysts had at best a cursory firsthand experience of analysis (a couple of walks with Freud in Vienna or Karlsbad, some letters from him interpreting their dreams), or were simply anointed by Freud, most of the next generation were either analyzed by Freud himself or underwent the increasingly organized training at one of the psychoanalytic institutes in Berlin, Budapest, Vienna, and London. But these institutes were headed by the members of the so-called Secret Committee, the innermost council of Freud’s “paladins,” who oversaw the correct development of psychoanalytic theory and technique. They exercised control to a large extent by analyzing the most promising of the candidates, or those who threatened to become troublemakers, and wielded considerable power by referring or not referring patients to trainees.

However, as the diagram shows, many of the leading concepts in contemporary psychoanalysis can be traced back, to a surprisingly large extent indeed, not to Freud himself, but to two of his erstwhile most intimate colleagues: the Hungarian Sándor Ferenczi and the Viennese Otto Rosenfeld, who called himself Otto Rank. Both were dismissed as dissidents when Freud fell out with them, and their work fell into oblivion for a long time. While homage is still paid to the Freudian heritage, the influence of his and his daughter’s genealogical line, representing the mainstream up to the 1960s and 1970s, is on the wane. (There are also some interesting crossovers and throwbacks, not represented in this chart, from the Jungian, Adlerian, and other families.)

So, what is the moral of the story? That the history of psychoanalysis is the story of a sect of fanatics, immunizing itself by a method of circular brainwashing and intricate networks of interdependence? An attempt to deliver ammunition to those who want to relegate psychoanalysis to the ashtray of history? This is certainly not my intention. For the most part, these were serious people who earnestly tried to help people and further science in the process. They still do. They experiment, learn from earlier blunders (this graph illustrates a few of them), and make their own. Even so, I confess that I am much more concerned about the current growth of the “desire not to know,” as Julia Kristeva puts it, and the seemingly triumphant success of the pharmaceutical cocktail over the spoken word. There once was a brilliant, if chilling, ad for a certain tranquilizer: “Not a pseudo-solution for problems, but a solution for pseudo-problems.”

I have worked long enough in psychiatry to know very well that drugs can be of great use, but as far as the endemic pseudo-problems of love and work are concerned (what Freud is said to have called “the cornerstones of our humanness”), I’d rather stick with the blundering proponents of the talking cure.

- See Journal de Genève, 5 February 1977.

Ernst Falzeder is a psychologist, psychotherapist, historian, translator, skiing instructor, and pianist, presently based in a small village in the Austrian Alps. He is the author of more than 100 publications on the history, theory, and technique of psychoanalysis. He recently edited The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Karl Abraham (Karnac, 2002).