Unwell

A short history of hypochondria

Brian Dillon

Variable, and therfore miserable condition of Man; this minute I was well, and am ill, this minute. I am surpriz’d with a sodaine change, and alteration to worse, and can impute it to no cause, nor call it by any name.

—John Donne, Devotions upon Emergent Occasions

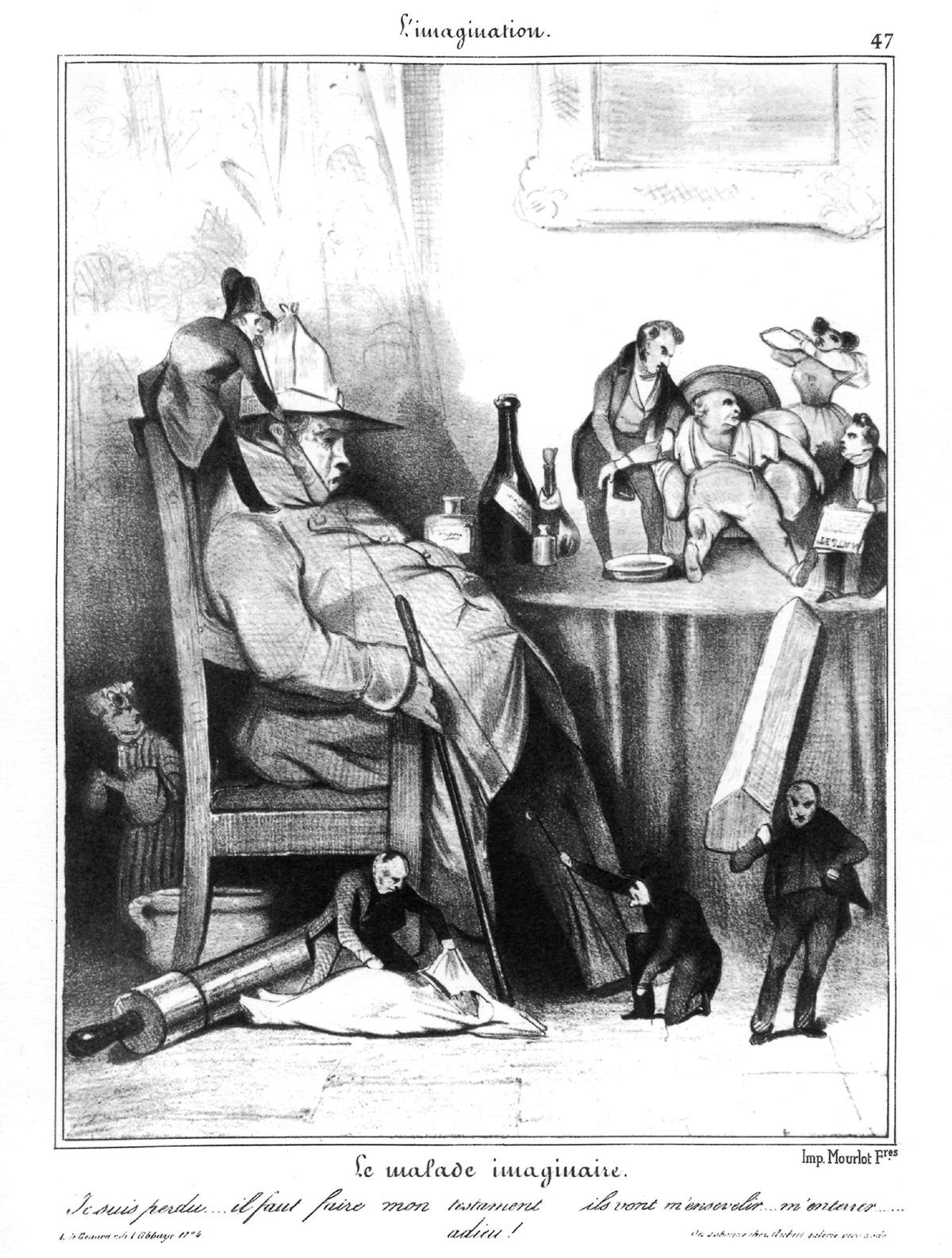

None of this would have surprised a seventeenth- century physician. Nor, as he concluded that his patient was suffering from hypochondria, would he have meant to imply that these ailments were entirely imaginary. Historically, hypochondria is first of all a physical disease, with a distinct, if often unruly, symptomatology. For the Greeks, the hypochondrium was the region of the abdomen just below the rib cage; Hippocrates and Celcus describe the area and its potential disorders. Plato, in the Timaeus, identifies this part of the body as the seat of both physical and exigent emotional urges: “That part of the soul which desires meats and drinks and the other things of which it has need by reason of the bodily nature, they placed between the midriff and the boundary of the navel ... and there they bound it like a wild animal which was chained up with man.” This intimacy between abdominal disorder and emotional upheaval prevails until the time of Robert Burton, whose Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) essays the first modern description of the scope of hypochondriacal affliction. Burton adduces a species of hypochondriacal melancholy, the definition of which already suggests the contemporary meaning of hypochondria: “Some are afraid that they shall have every fearful disease they see others have, hear of, or read and dare not therefore hear or read of any such subject.” Like melancholia, hypochondria here starts to lose its connection to an earlier, humoral, model of the body’s economy, and begins to be understood in terms of a more general character or temperament. The hypochondriac becomes a personality type, a stock figure whose comic potential—his suggestibility, his enthrallment to quack doctors and apothecaries—is exploited in Molière’s Le Malade imaginaire (1673).

Sir George Cheyne, in his influential study The English Malady (1733), suggests a more practical understanding of a disorder that seems endemic to his own nation. Fully one third of “people of condition” are said to suffer from hypochondria at any one time: a result, he says, of their very wealth and luxury. Hypochondria is occasioned by “the Moisture of our Air, the Variableness of our Weather ... the Richness and Heaviness of our Food, the Wealth and Abundance of the Inhabitants ... the Inactivity and sedentary Occupations of the better Sort ... and the Humor of living in great, populous and consequently unhealthy Towns.” The two most prominent British hypochondriacs of the century—Samuel Johnson and James Boswell—seem to have agreed with Cheyne (though Johnson deprecated his conclusion that hypochondria and genius went together too). Boswell wrote of his friend’s hypochondria: “all his labors and all his enjoyments were but temporary interruptions of its baleful influence,” while Johnson counseled his biographer to refrain from drunkenness and sexual excess, lest “horrid ideas” should take hold of his weakened mind.

Johnson may have been using the term in an older sense that was still extant: hypochondria was more or less identical to melancholia. But Boswell’s deployment of it seems more precisely in tune with the idea of a heightened anxiety regarding illness and death. In 1763, Boswell went to Utrecht to study. His mind had already been “strangely agitated,” and his mood “somewhat melancholy,” while dining with Johnson at the Turk’s Head the night before his departure. On disembarking, he was seized almost immediately with “a deep melancholy. I groaned with the idea of living all winter in so shocking a place.” He speaks of “minute fretful pains,” of a mind “so tender and sore that every thing frets it,” of “a sort of complication of all diseases together, with almost madness added to them.” Years later, in a series of seventy essays written under the guise of “The Hypochondriack,” he wrote of his own suffering, he said, in “the hope of contributing to the relief of many as unhappy as I have formerly been.” Like Johnson, he imagines that his hypochondria has something to do with a certain laxness in his bodily and intellectual habits: luxury and laziness provide a way in for fresh fears and visions.

This madness, in the Romantic period, is called hysteria; its (generally) masculine equivalent is hypochondria. (The novels of Jane Austen are important in this regard, but so too are the alienated, oversensitive characters of Hans Christian Anderson, himself a miserable hypochondriac.) In a sense, all of Romantic literature and art is intensely hypochondriac: unable to establish a solid boundary between the self and the world, given to guilt-ridden self-medication (as in the cases of Coleridge and De Quincey), or obsessed by the details of impending death (Keats). The most dramatic hypochondriacs, however, are not the poets of high Romanticism, but those who came later, whose constitutions seem to have been marked by the sickly fears of their predecessors and increasingly alarmed by the scientific discoveries of their contemporaries. Alfred Lord Tennyson is a particularly poignant example: a poet who seems to have thought that his visionary calling literally involved seeing things. He became debilitatingly obsessed by the floaters that hovered before his eyes: “these ‘animals’ ... are very distressing,” he wrote. His particular fantasy of bodily invasion shows the idea of infection stealthily invading the imagination of the nineteenth-century hypochondriac.

But perhaps the most rigorous observer of the relationship between real illness and the mind’s invented ailments is Charlotte Brontë. She seems to have experienced two dramatic bouts of hypochondria. The first overcame her at a lonely boarding school on Dewsbury Moor: “I endured it but a year, and assuredly I can never forget the concentrated anguish of certain insufferable moments, and the heavy gloom of many long hours, besides the preternatural horrors which seemed to clothe existence and nature and which made life a continual waking nightmare.” She suffered the second in Brussels in 1843, when she was left alone during the summer holiday at the school where she was working. Brontë dramatizes this second crisis in Villette: her heroine Lucy Snowe descends into a fog of melancholy and obsession when she is left alone during the summer vacation. Having recovered from her own uprising of hypochondriacal passion, she recognizes it instantly in another’s face, glimpsed at the theater: “Those eyes had looked on the visits of a certain ghost—had long waited the comings and goings of that strangest spectre, Hypochondria … dark as Doom, pale as Malady, and well nigh strong as Death. … And she freezes the blood in his heart, and beclouds the light in his eye.” Brontë’s own sufferings in this regard might plausibly be said to have their origin in the scenes of sickness and death that she witnessed in the family home at Haworth; an early encounter with illness or bereavement has long been posited as one of the triggers of adult hypochondria. But Brontë also means something else by her self-diagnosis: a certain sensitivity that is bound up, in Romantic fashion, with her status as an aspiring writer.

A celebrated case of the era demonstrates the perplex of actual and fantastic ailments that can confuse the physician faced with a persistent somatizer. In his Recollection of the Development of My Mind and Character, Charles Darwin considers the effects on his scientific career of a lifetime’s sickness, much of which was mysterious at the time and remains unexplained still. “Ill-health,” he writes, “though it has annihilated several years of my life, has saved me from the distractions of society and amusement.” His heart, stomach, and head were affected; he was prone to vertigo, muscle spasms, vomiting, cramps, and flatulence; he was persistently exhausted, depressed, unable to sleep, likely to become nervous without his wife, and to be overcome by “dying sensations.” Darwin saw over twenty doctors, but the underlying cause of his sickness eluded all of them. Many treatments were canvassed, including laudanum and electrical stimulation of the abdomen; the only therapy that afforded Darwin any relief, he claimed, was regular immersion and inundation at Dr. James Gully’s Water Cure Establishment at Malvern. Darwin would certainly not have cared to admit that the ailments that kept him productively secluded from society were the products of a diseased imagination. But he seems to have had some inkling that his fears and fancied illnesses were useful mechanisms by which to control the world around him—a recurring theme in the psychoanalytic literature on hypochondria. In fact, Darwin’s ill-health affected not just his own career, but, inevitably, the lives of his family; his wife came to devote most of her time to scheduling her husband’s existence in accordance with his physical or emotional state; his children inherited his sickly habits.

What was behind Darwin’s abundant symptoms? Numerous explanations have been ventured, ranging from tropical disease to a mind unhinged by the enormity of his scientific discoveries. It seems certain that some somatic element was involved, though to what precise extent it is impossible to say. His mother died when he was eight years old—the early loss of a parent is, according to one model of the genesis of hypochondria, a likely cause of later health anxiety—though he seems to have been a happy child. It was said by some that his relationship with his wife seemed more like that of a child to his mother. Darwin himself claimed that his symptoms were brought on by professional demands: lectures, correspondence, and the like, rather than actual scientific work, which rather benefited from his incapacity. Two organic diseases, which he might have acquired on his travels, have been conjectured—Chagas disease and Ménière’s disease—but the case for either remains inconclusive. Most dramatically, certain anti-Darwinists among the American religious right have claimed that his imagined ill-health was the product of madness, itself occasioned by his guilt at having overthrown Christian doctrine.

Marcel Proust, whose fiction consists not in the wholesale invention of a novelistic world, but precisely in the intensification of his own experience, seems to have grasped both the inherent absurdity of his own hypochondria and the creative uses of oversensitivity. He wrote: “For each illness that doctors cure with medicine, they provoke ten in healthy people by inoculating them with the virus that is a thousand times more powerful than any microbe: the idea that one is ill.” But he also learned at an early age, as his biographer Ronald Hayman puts it, “how to snatch strength out of weakness.” He was genuinely ill, most seriously with asthma, for much of his life. Asthma, like tuberculosis and epilepsy, was thought to have some psychogenic origin, if not quite to be a pure product of hypochondria. Proust’s own hypochondria was not only a matter of thinking himself ill, but of imagining his real ailments more debilitating than they really were, and of bringing on himself a degree of decrepitude that was surely unwarranted. It was said that he died because he was unable to open a window or to light a fire: he retreated into invalidism as into a psychic refuge, a place from which he could reimagine the world he was leaving behind. The first step in this progressive detachment from life was his habit of sleeping during the day and socializing, and later working, during the night. He shut out sound, light, and air, dosed himself with opium, caffeine, and barbital (“you’re putting your foot on the brakes and the accelerator at the same time,” admonished a friend) until, bedridden, all he could do was write.

The exemplary twentieth-century hypochondriac is Howard Hughes; his medical history is a record of the countless health scares and minor neuroses that afflicted the century, and which are merely magnified in his own case. Both his parents seem to have worried unduly about the physical well-being and emotional “super-sensitivity” (as his mother put it) of their son. Hughes’s mother expressed endless fears about his teeth, his bowels, his inability to socialize with other children, and (not unreasonably at that time) the threat of polio. As a young man, he seemed to continue her compulsions in his own strange behavior: he became obsessed, for example, with the size of peas, and is said to have employed a special fork to grade them as he ate. It was only later, however, after a series of air crashes had left him with head injuries and an addiction to narcotics, that his fears became truly baroque, elaborated by the ease with which his whims could be indulged. Claiming that he wanted to live longer than his parents, he feared infection to the extent of avoiding shaking hands and eventually ordering his staff not even to look at him for fear of contagion. The stories attached to his later life are well known: he stored his urine in jars; he wore Kleenex boxes as shoes; he installed dust filters in his cars; he destroyed successive hotel rooms as he tried to seal his living quarters from the outside world. He may even have attempted to bribe Presidents Johnson and Nixon to stop nuclear tests in the Nevada desert, such was his fear of radiation. At the time of his death, such eccentricities were the subject of ghoulish interest on the part of a public for whom “hypochondriac” had lost all its connotations of creative sensitivity.

The contemporary hypochondriac, by contrast, finds himself once again, after almost a century, accorded the respect of a sympathetic diagnosis. The story of how the most exasperating and unprioritized patients came, after a long absence, to be accepted back into the company of the authentically ill, has to do first of all with the theory, advanced mid-century, that hypochondria is essentially masked depression. The sufferer has projected her (most of those who present with debilitating worries about their health are now women) psychic pain onto her body, and imagined a set of symptoms that will explain her unease in the world. In recent years, however, this theory, essentially derived from Freud, has been supplanted by the suggestion that hypochondria is best understood and treated as part of a continuum of anxiety disorders that includes obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. The change has crucial consequences for treatment: the use of anti-depressants has given way to cognitive behavioral therapy. The new recognition of “health anxiety disorder” also means, of course, that new communities of the overly imaginative have come together to console each other, and there now exist many support groups for those who want to learn how to cope with what they know is not there.

This article is published as part of Cabinet’s contribution to documenta 12 magazines, a worldwide editorial project linking over seventy print and online periodicals, as well as other media. See www.documenta.de for information on documenta 12 and this project.

Brian Dillon is UK editor of Cabinet, and writes regularly for Frieze, Modern Painters, and Art Review. His memoir In the Dark Room (Penguin) won the inaugural Irish Book Awards non-fiction prize, 2006. He is working on Tormented Hope: Nine Hypochondriac Lives, to be published in 2008.