Salt and Pepper

Season to taste

Implicasphere

Linguistically, salt and pepper often seem inseparable, conjoined by an ampersand as if never apart. The phonetic rhythm of the coupling implies an ancient allegiance, and their implicaspheres—the radii of associations that encircle each word in the imagination of those who hear or read or simply consider them—certainly overlap. Many a recipe includes both ingredients on the same line as if they were one, and a dining table that cares about presentation insists on matching receptacles. When faced with a cruet set that brings together the two elements in a single decorative entity, it is hard to remember the profundity of their separate histories. Yet we at Implicasphere think that their individual qualities are not to be sneezed at.

Mineral salt and vegetable pepper changed the world. Black pepper pounded the spice trail for centuries, becoming as important as money. Salt too inveigled its way into the vocabulary of exchange, providing the root for such words as “salary” and “salute.” State power from China to the Ottoman Empire has been built or broken on the salt and spice trades, and was emphatically challenged when, in 1930, Gandhi contravened the British Salt Law by picking up a salt crust on the shore of the Arabian Sea.

But the metaphysical and physiological importance of these substances lies beyond their material worth. Both are irritants: pepper invades the body most notoriously through the nostrils, while salt finds more dissolute and even magical channels into our innermost chambers. From Haiti to the Isle of Man, salt is used to ward off evil. Perhaps this is because salt is a preserver and embalmer, resisting decay and corruption. For Plutarch, this pure, white matter was linked with the soul, the quintessence of life, since it defies mortification of the flesh. Such connotations of permanence are performed in the covenant of salt, where it symbolically seals a binding pledge. But for one ancient historian, its powers of immortality corrupt the earthly body, bringing damnation: Eve’s original sin wasn’t to taste an apple but salt.

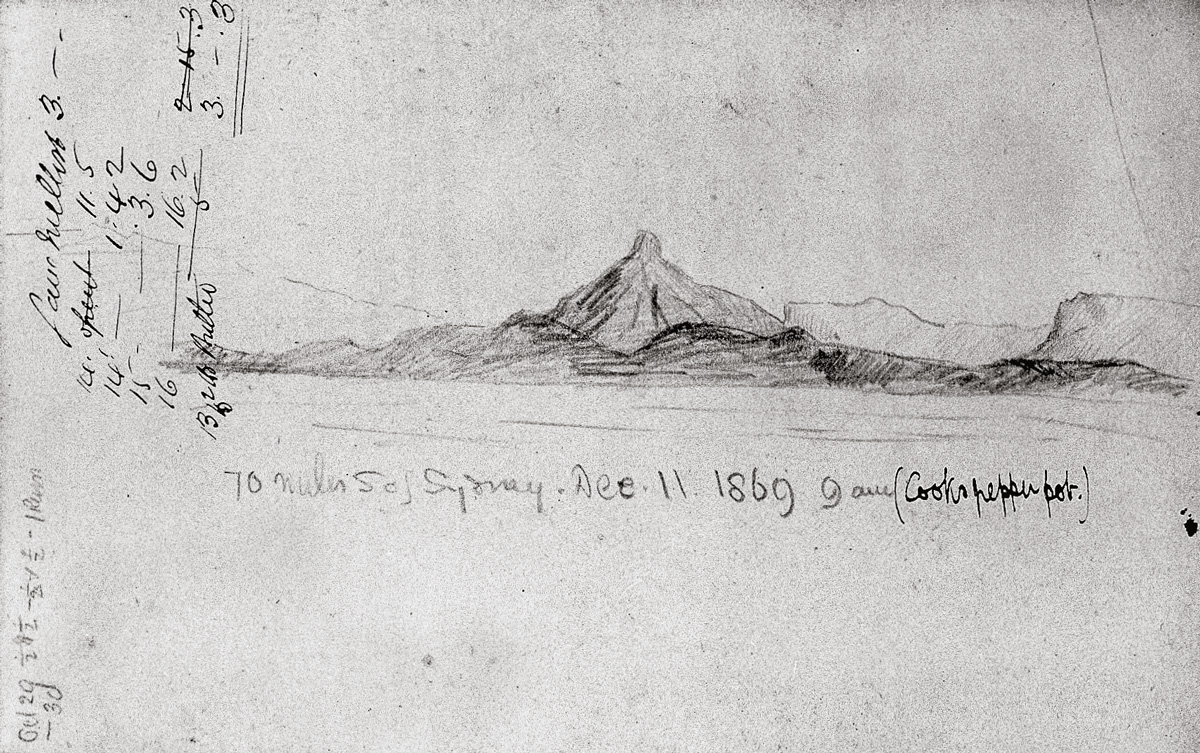

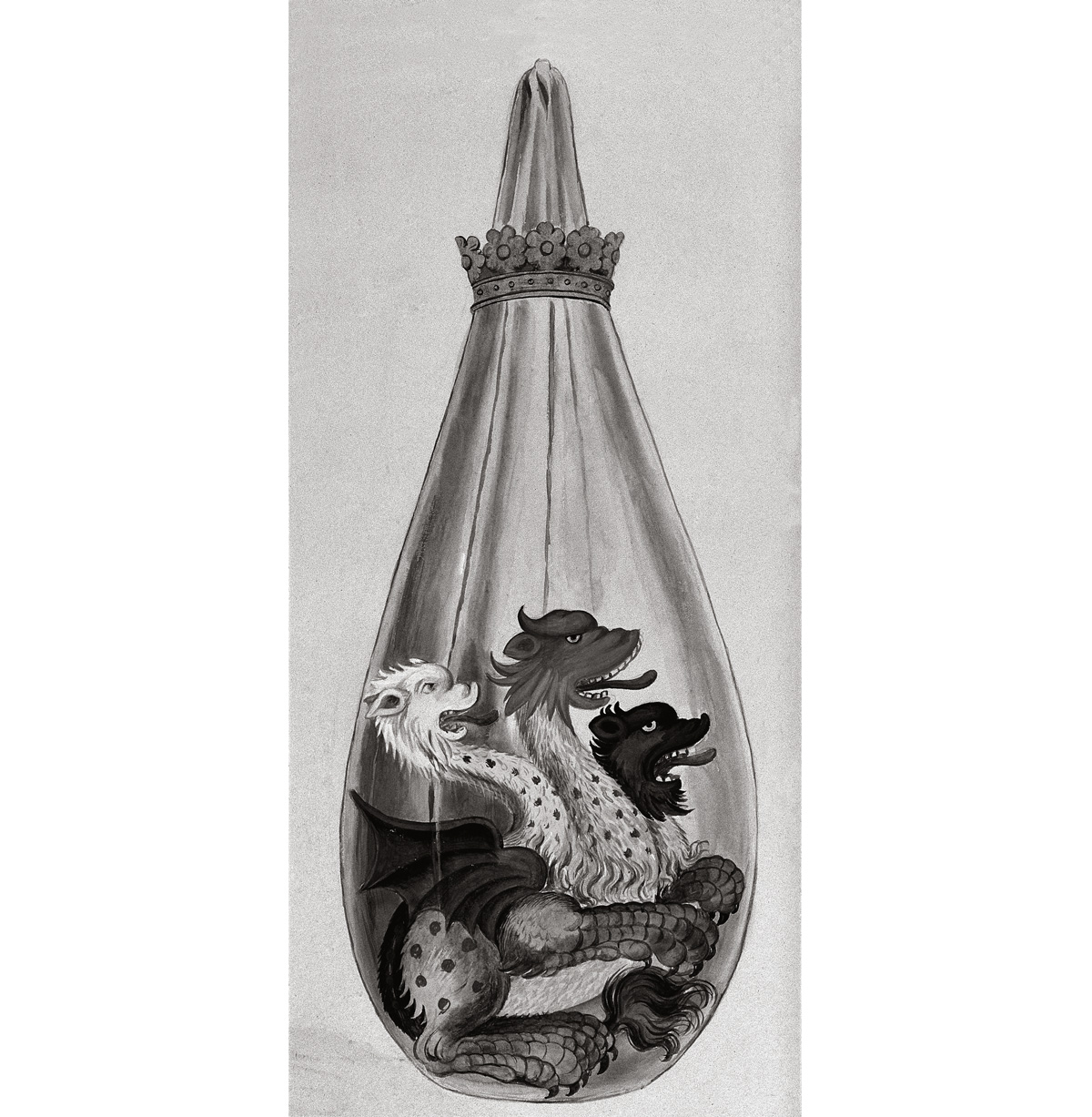

Pepper is altogether more flighty, becoming an adjective or verb applied to what is intermittent or scattered. Its potency goes beyond the palate, pepping up libido according to the legendary appetites of latter-day troubadours or wince-making modern sex recipes; peppercorns were found stuffed up the nostrils of Rameses II, perhaps to bring him vigor in the afterlife. The engorged shape of the pepper pot, meanwhile, lends itself to many a visual analogy, from Monty Python’s dumpy old women of Little England to the je ne sais quoi of the playboy Porfirio Ruberosa. Salt’s sexual connotations are also rampant—“salacious” comes from the Latin salax, a man in love, or a “salted state.” For psychoanalysis, the misfortune of spilling salt is that of premature ejaculation.

Salt’s practical uses, from preserving beef to freezing Victorian ice rinks, have come to overshadow its symbolic import. Similarly, pepper’s magical properties as a stimulant have been more or less forgotten. In an age when we can manufacture salt artificially or grow pepper on a mass scale, we have little sense of their sacred value. This issue therefore adds a dash and a pinch of their vast histories to our tiny implicaspherical plate.

Good old static electricity comes to the fore in this trick, which is perfect for the dinner table.

Props: a salt shaker, a pepper mill, a comb

Advance preparation: Charge the comb with static electricity. For instance, leave the table and comb your hair thoroughly to get a strong charge.

Claim to make the pepper disappear from a pile of salt. Shake salt into a small pile on the table and top it with a bit of pepper.

Dramatically whisk the comb from your pocket and pass it over the salt and pepper. The pepper will adhere to the comb. For extra effect, palm the comb as you pass it over the salt and pepper, so no one suspects static electricity.

—Jay Marshall, How to Perform Instant Magic (Folkestone, UK: Bailey and Swinfen, 1980).

In the mid-1950s, at the height of [Porfirio Rubirosa’s] glory and success, the Cuban guitarist and composer Eduardo Saborit wrote a hit song that bluntly asked the musical question … “What Have You Got, Rubirosa?” …

What indeed?

Recall the testimony of Flor de Oro concerning her honeymoon: “When it was over my insides hurt a lot.” …

Jerome Zerbe, a society photographer who snapped dozens of celebrities at New York’s famed El Morocco nightclub, was said to have gotten into his cups at Deauville and, on a dare, followed Rubi into the men’s room. He skittered out gleefully, the story went, with the intelligence, “It looks like Yul Brynner in a black turtleneck!”

Tabloid magazines brushed as close to the subject as they could, calling him the “ding-dong daddy” after a phrase made famous in country and soul songs.

Truman Capote described it in Answered Prayers—without ever seeing it, of course—as “that quadroon cock, a purported eleven-inch café-au-lait sinker thick as a man’s wrist.” …

Jimmy Cromwell, the sportsman first husband of Doris Duke, had seen or at least heard tell of it: He referred to Rubi as “Rubberhosa.” …

And cheeky waiters at Continental restaurants would celebrate it perennially, if not always knowingly, referring in knavish fashion to the largest peppermill in the house as—what else?—the “Rubirosa.”

—Shawn Levy, The Last Playboy: The High Life of Porfirio Rubirosa (London: Harper Perennial, 2006).

Government and Virtues.—

All the peppers are under the dominion of Mars, and of temperature hot and dry, almost to the fourth degree; but the white is the hottest. It comforts and warms a cold stomach, consumes crude and moist humours, and stirs up the appetite. It dissolves in the stomach or bowels, provokes urine, helps the cough, and other diseases of the breast, and is an ingredient in the great antidotes; but the white pepper is more sharp and aromatical, and is more effectual in medicine, and so is the long, being used for agues, to warm the stomach before the coming of the fit. All are used against the quinsy, being mixed with honey and taken inwardly and applied outwardly, to disperse the kernels in the throat, and other places.

—Nicholas Culpeper, Culpeper’s Complete Herbal: Consisting of a Comprehensive Description of Nearly All Herbs from Their Medicinal Properties and Directions for Compounding the Medicines Extracted from Them (London: Foulsham, 1935).

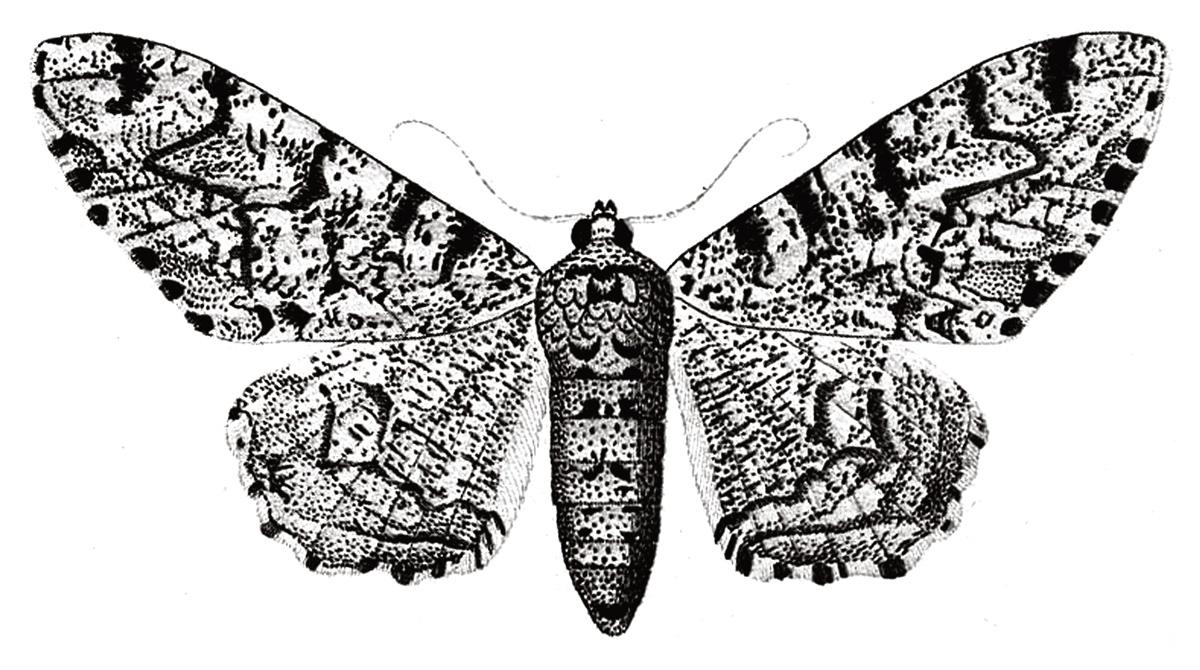

Under the surface of the bare-bones tale allotted to the peppered moth in every textbook, there lies, like a fading palimpsest, a human story, set in the little-known community of moth collectors. In fact, this unlikely protagonist—a mere moth—has engendered a century of struggle, for, contrary to popular wisdom, Darwin’s theory of natural selection was on shaky ground in the first part of the twentieth century. Apart from admittedly artificial laboratory studies of fruit flies, experimental evidence for Darwinian theory was lacking. …

The night-flying peppered moth, Biston betularia, normally off-white with a freckling of white scales, has been an object of scientific curiosity since Darwin’s own time. In the mid-nineteenth century a dark (“melanic”) form of this moth appeared in the industrialized Midlands of the British Isles. These strange black moths thrived and grew more numerous wherever there was factory smoke fouling the atmosphere, and some people began to think that Darwin’s theory of evolution might explain why. Resting against soot-blackened backgrounds the melanic moths were nearly invisible to the birds, and so escaped being preyed upon. Thus more of them survived to reproduce. In rural areas it was just the opposite. …

Neat and tidy mirror images, these twin demonstrations became the most celebrated experiment ever in evolutionary biology. By the 1960s it had conquered all the textbooks, influencing the minds of four decades of biology students. …

At the very moment that the peppered moth experiments were establishing the Oxford biologists as masters of their world, their personal and professional relationships were disintegrating in a miasma of recriminations, intrigue, jealousy, back-stabbing and shattered dreams. They conceived the evidence that would carry the vital intellectual argument, but at its core lay flawed science, dubious methodology and wishful thinking. Clustered around the peppered moth is a swarm of human ambitions, and self-delusions shared among some of the most renowned evolutionary biologists of our era.

—Judith Hooper, Of Moths and Men: Intrigue, Tragedy and The Peppered Moth (London: Fourth Estate, 2002).

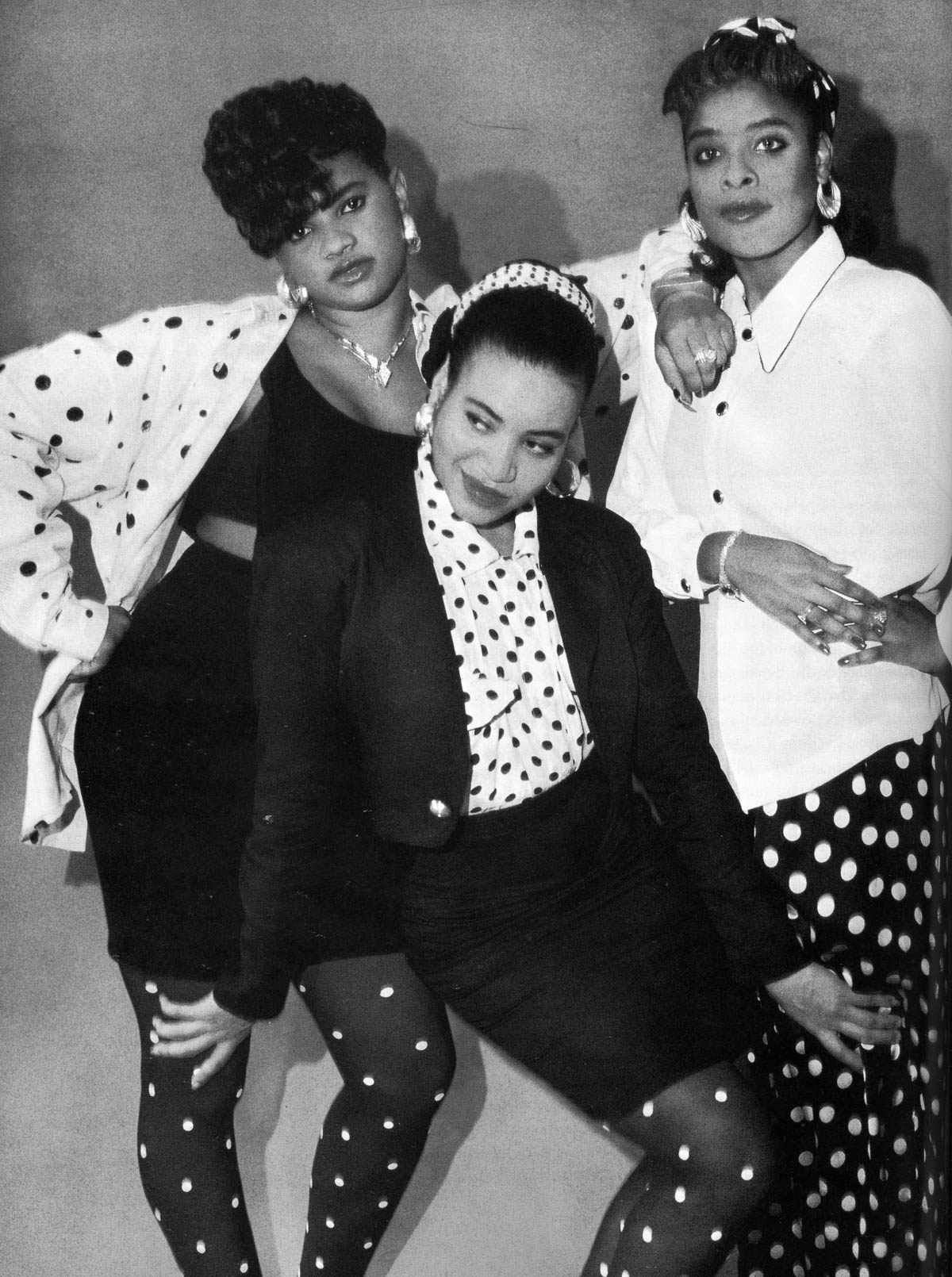

Salt and Pepa’s here, and we’re in effect

Want you to push it, babe

Coolin’ by day then at night working up a sweat

C’mon girls, let’s go show the guys that we know

How to become number one in a hot party show

Now push it

Ah, push it—push it good

Ah, push it—push it real good

Ah, push it—push it good

Ah, push it—p-push it real good

Hey! Ow!

Push it good!

Oooh, baby, baby

Baby, baby

Oooh, baby, baby

Baby, baby

—Salt-N-Pepa, “Push It,” A Salt with a Deadly Pepa, 1988.

In November 1997 Canada hosted a meeting of government leaders from countries surrounding the Pacific Ocean. The annual gathering of the heads of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) “economies” brought important world leaders to Vancouver at a time of crisis for many Asian economies. The meeting provided them with a unique opportunity to explore some urgent issues. …

The lasting image of the summit, seared in Canada’s collective memory, was that of a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television cameraman being pepper-sprayed by an irate-looking police officer. …

The current investigations focus on a wide range of alleged unlawful police conduct, including a bit of “roughing up,” excessive use of pepper spray, arrest on flimsy grounds, and the imposition of unlawful release conditions. There have been allegations that police officers assaulted and detained peaceful individuals for displaying signs, or for using cell phones, or for possessing megaphones or other amplifying equipment—none of which is even remotely unlawful. There have also been complaints that individual police officers used pepper spray to punish (if proved, they would be guilty of criminal assault) rather than to subdue lawbreakers or to effect lawful arrests (which, in proper circumstances, is permissible). Other police officers are said to have told Canadians that UBC, in effect, was a “Charter-free zone” (there is no such thing in Canadian law), while still others are alleged to have engaged in sex-discriminatory strip searches and prophylactic arrest.

—Pepper in Our Eyes: The APEC Affair, ed. W. Wesley Pue (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000).

JOHN CLEESE: Now there the father used irritation to achieve a purpose. But there is a particular type of middle-aged woman who uses irritation as a way of life. It’s the only thing she’s really good at. She’s roughly this shape. Like a pepperpot. There’s a couple of them over there. Yoo hoo!

TWO PEPPERPOTS: Yoo hoo!

CLEESE: A pepperpot’s life ambition is to be in the audience at a quiz show. And she is to be found in shopping areas blocking the pavement, tormenting babies, spreading rumours and spending a fortune on bargains. She enjoys worrying and being shocked. Individually she is intolerable, in a group horrific. Here is a squadron of them in a cinema irritating a bonafide cinemagoer. First they react in certain organised ways.

THREE PEPPERPOTS: Ooh! Aah! Well I never! Tut tut tut! [Repeat four times]

CINEMAGOER: Shhhhh!

THREE PEPPERPOTS: Ooh! Well I never!

CLEESE: Then they commentate on the film. … Next they get carried away by details. … And finally they have a devastating reaction to certain jokes.

—Dialogue from How to Irritate People, 1968, written by John Cleese, Graham Chapman, Marty Feldman, and Tim Brooke-Taylor, and directed by Ian Fordyce.

[In Le Paradis sexuel des aphrodisiaques (1971), Marcel] Rouet cites the Kama Sutra as his authority that ground pepper can be applied directly to the penis before intercourse, in which event the lucky recipient of his spiced attentions will be entirely at the disposal of the peppered penis.

—Jack Turner, Spice: The History of a Temptation (London: Harper Perennial, 2004).

Wicks pepper took in moderation,

While this was Master Brown’s oration:

“Why, Mr. Wicks! I never heerd,

That you ov pepper was affeerd,

Shake on! Shake on! Off weth the cover;

Your shaking then will soon be over:

I spose the pepper must be good,

And genteel, too, because tes rud.”

Brown took the Box and well he shook it,

As he lik’d pepper, so he took it;

It was cayenne, which should be told ye,

But Brown shook on and pepper’d boldly.

Indeed, poor Brown shook on, ‘tis said,

Until his fish was quite red.

The mixing process done, or nigh it;

Brown took a mouthful and would try it.

Oh agonies! Oh horrors! Oh such burnings!

Such bad contortions, twists and turnings,

Brown, quickly springing to his feet,

With tears spat out the burning meat;

Then with a clutch the water seized,

And pour’d it where the pepper blaz’d;

Again he drank—again he’d pause;

Again he lav’d his burning jaws,

His eyes seem’d starting from his head,

“I’m all a fire!” he fiercely said.

—I. T. Tregellas, “Farmer Brown’s Blunders,” Cornish Tales, in Prose and Verse (Truro, UK: Netherton and Worth, n.d. [1860s]).

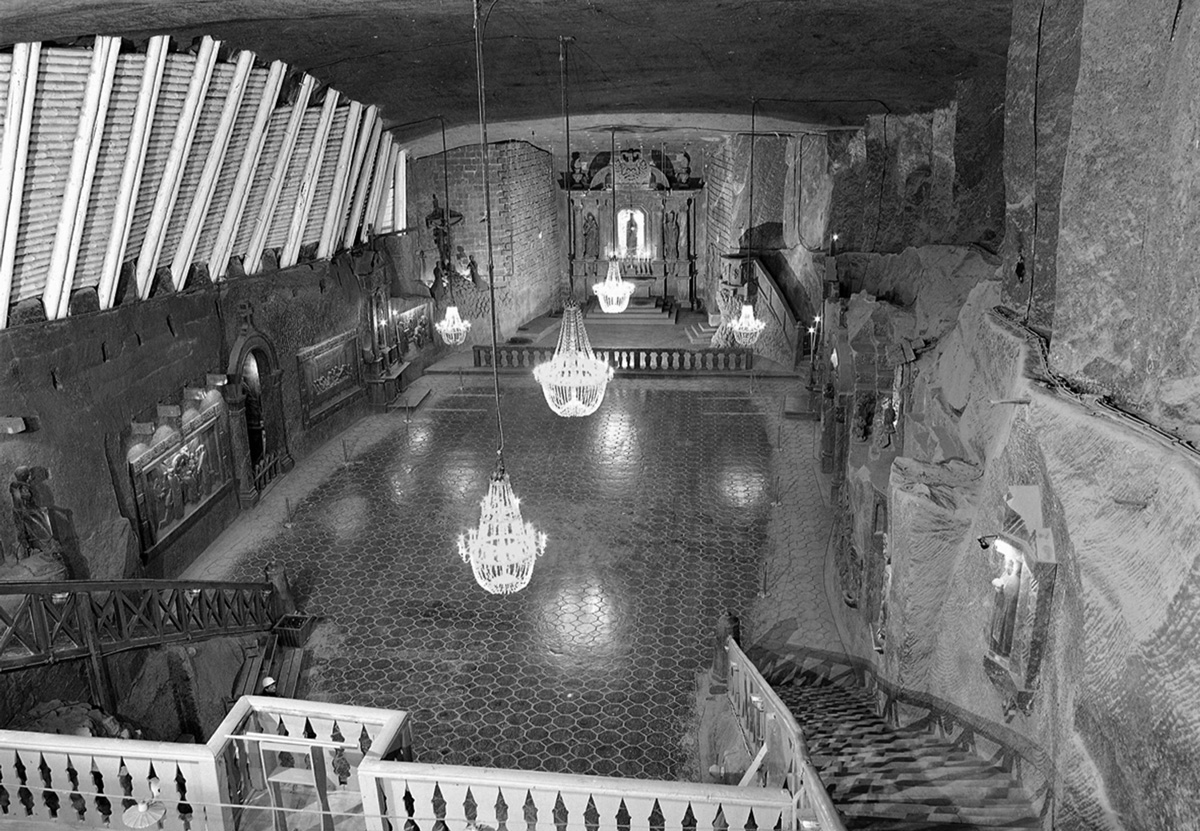

[The salt mines of Wieliczka] appeared like huge subterranean vaults of gothic architecture. Wooden steps leading from gallery to gallery were attached to the walls. The torches and lanterns of the workmen lighted up the walls. One who stood on the highest gallery lighted a large piece of oakum and threw it down the shaft. It burst into a flame and lighted up the glittering vault to its highest summits and revealed fresh and unknown depths below. The old mines are very picturesque, particularly where the roofs dividing the stories [sic] have fallen in, thus opening abysses to the view at which the spectator shudders. The new mines with their regular beams and props, massive even walls, and strong neat chambers, are less wild and striking. In some caverns, immense chandeliers, cut out of the salt, have been hung up. In one, which was called the Great Hall, hung such a chandelier, 35 feet in height, and 60 in circumference. In another, the Lentov chamber, were six of these chandeliers.

—C. T., The Natural History of Common Salt: Its Manufacture, Appearance, Uses, & Dangers, in Various Parts of the World (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1850).

The ships that carry salt breed abundance of mice; the females, as some imagine, conceiving without the help of the males, only by licking the salt. But it is most probable that the salt raiseth an itching in animals, and so makes them salacious and eager to couple.

—Plutarch, Symposiacs (Book 5), trans. T. C., in Plutarch’s Morals, vol. 3, ed. William W. Goodwin (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company: 1874).

It seems a long way from salary to salt but it is from this that the word is derived … from the Roman custom of paying soldiers and sailors a quantity of salt as part of their wages. It was known as the salarium from the latin sal meaning salt, and also gives rise to the expression worth his salt meaning that a man was worth his keep. Salt was not considered quite so precious by northern European sailors but in the early days of sail it was still a very valuable commodity where it was used principally to preserve meat, for eating (salt tablets are still issued on most ships in the tropics) and even as a crude antiseptic. It is from this that we get the expression rub salt in the wounds.

—Bill Beavis and Richard G. McCloskey, Salty Dog Talk: The Nautical Origins of Everyday Expressions (St. Albans, UK: Granada, 1983).

LONDON, Dec. 16 (Reuters)—Geologists say they have pinpointed the probable site of the biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah and worked out a theory of why Lot’s wife was reported to have ended up as a pillar of salt.

The findings by two British geologists working in Canada were printed in the Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology on Friday.

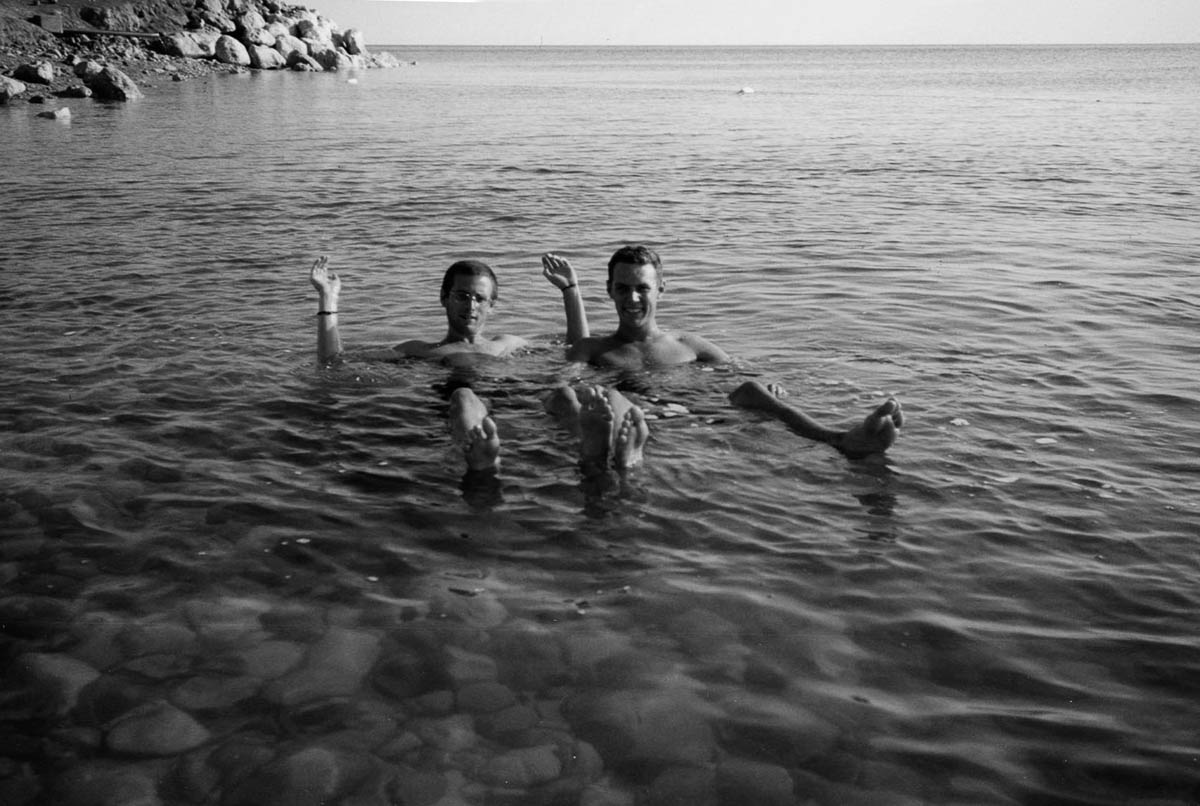

The geologists, Graham Harris and Anthony Beardow, analyzed local soil and rock to conclude that Sodom and Gomorrah were probably located on a Dead Sea peninsula.

While the rough location of the cities has long been suspected, the authors said they used the latest geological thinking to trace them to a specific peninsula and work out the reason they vanished around 1900 B.C.

“This is an attempt to use modern geological perspectives to look into a very racy story, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and solve a fascinating historical problem,” said Peter Styles of the Journal staff.

According to the Old Testament, the cities were destroyed by fire and brimstone in retribution for the sinfulness of their residents. Since Lot was considered a good man, he was warned of God’s punishment. However, his wife disobeyed the sole condition of not looking back and was transformed into a pillar of salt.

The geologists said that Lot’s wife did not appear to turn into a pillar of salt because she dared to look back but because of the briny nature of the Dead Sea. But the research shows it was more likely a case of mistaken identity. Mr. Harris said by telephone from Canada that the Dead Sea was full of salt floes that might have been thrown up by surging water to resemble a female outline. “Hence legend is created out of what can now be explained as a simple geological phenomenon,” he said.

—The New York Times, 17 December 1995.

SALT: Just because you’ve got loads of holes you think you’re special.

PEPPER: No I don’t I just think I’m fortunate.

SALT: You do, you really think you’re better than me don’t you?

PEPPER: No, I’ve just got more holes.

SALT: You can’t stop can you?

PEPPER: Look, it’s just how it is. I’ve never actually counted my holes you know. OK what have I got, seven, eight maybe, and you’ve got one. But in the whole world there are millions of holes and compared to that we’re both insignificant.

SALT: You patronising cruet. I’m leaving you for the vinegar.

PEPPER: Suit yourself but it’s only got one hole.

—John Hegley, The Family Pack (London: Methuen, 1997).

Meanwhile Pantagruel scattered the salt from his dinghy into their gaping mouths in such quantities that the poor wretches barked like foxes.

“Oh, oh, Pantagruel, Pantagruel,” they hawked. “Why do you add further heat to the firebrands in our throats?”

Suddenly Panurge’s drugs began to take effect and Pantagruel felt an imperious need of draining his bladder. So he voided on their camp so freely and torrentially as to drown them all and flood the countryside ten leagues around. We know from history that had his father Gargantua’s great mare been present and likewise disposed to piss, the resultant deluge would have made Deucalion’s flood seem like a drop in the bucket. A mare of the first water, Gargantua’s; it couldn’t relieve itself without making another Rhône or Danube. The soldiers sallying from the city saw the whole thing.

“The enemy have been hacked to bits,” they exulted. “See the blood run!”

But they were mistaken. What they believed in the glow from the burning camp and the dim moonlight to be the blood of slaughtered enemies was but the wine from our giant’s bladder.

The enemy now awakened thoroughly to see their camp blazing on one hand and Pantagruel’s urinal inundation on the other. They were, so to speak, between the fiery devil and the deep Red Sea. Some vowed the end of the world was at hand, bearing out the prophecy that the last judgement would be by fire. Others were being persecuted by the sea-gods Neptune, Proteus, Triton and others. Certainly the waters flowing over them were salty.

—François Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel, trans. Jacques LeClercq (New York: Random House, 1944).

Thus, in accordance with the very clear evidence of nature, it is declared that man’s fall, or disease and death, was occasioned by his departure from the vegetable kingdom, that is, the tree of life, and partaking of crude mineral substance, the source of death. …

It is very evident that man’s degeneration has been occasioned by his departure from the vegetable kingdom, whose fruits were appointed for his food, and making use of mineral substance which had not, by the vegetable elaboration, been refined, purified, and converted into a state fitted for his nourishment; and as salt is a substance more likely than any other, belonging to the mineral kingdom, to have invited him to its use, there is the greatest reason to believe that the eating of salt did constitute the act of transgression alluded to by Moses: and from the inculcations of the wise men of Egypt respecting salt, it may justly be concluded that they were well aware of that circumstance.

—Robert Howard, Revelations of Egyptian Mysteries, with a Discourse on Health (London: Nichols and Company, 1881).

The vagina, the penis and the scrotum once made a journey together. They went far away to a distant place to buy salt. As they completed this business, they set about again together on the journey back, each one carrying its own load of salt.

After some time, it began to rain. The vagina said to the others, “It’s raining, your salt will become wet and melt if you carry it on your heads. Give it here to me. See, I put my salt in my opening. There the rain can’t get in and the salt stays dry.” The penis said, “Take my salt and keep it safe in your opening so that it doesn’t get spoilt by the rain.” The vagina took the penis’s salt into her opening. The penis asked the scrotum, “And you want to let your salt get spoilt by the rain?” The scrotum said, “If only!” He carried his salt further himself.

It’s from this that the penis always seeks the vagina, because she has the tastiest morsels (the salt!), and that the vagina always wants salt (semen) from the penis, but that the scrotum hangs indifferently besides them.

—Leo Frobenius, “Der Salzeinkauf,” Schwarze Seelen: Afrikanisches Tag- und Nachtleben (Berlin: Vita, Deutsches Verlagshaus, 1913). Trans. Maitreyi Maheshwari.

When sea-salt is made into a paste with litharge, it is decomposed, its acid unites with the litharge, and the soda is set free. Hence Turner’s patent process for decomposing sea salt, which consists in mixing two parts of the former with one of the latter, moistening and leaving them together for twentyfour hours. The product is then washed, filtered, and evaporated, by which soda is obtained. A white substance is now left undissolved; it is a compound of muriatic acid and lead, which, when heated, changes its colour, and forms Turner’s yellow; a very beautiful colour, much in use among coach-painters.

—Daniel Young, Young’s Demonstrative Translation of Scientific Secrets; or a Collection of above 500 Useful Receipts on a Variety of Subjects (Toronto: Rowsell and Ellis, 1861).

Evil spirits detest salt. In traditional Japanese theatre, salt was sprinkled on the stage before each performance to protect the actors from evil spirits. In Haiti, the only way to break the spell and bring a zombie back to life is with salt. In parts of Africa and the Caribbean, it is believed that evil spirits are disguised as women who shed their skins at night and travel in the dark as balls of fire. To destroy these spirits their skin must be found and salted so that they cannot return to it in the morning. In Afro-Caribbean culture, salt’s ability to break spells is not limited to evil spirits. Salt is not eaten at ritual meals because it will keep all the spirits away.

—Mark Kurlanksy, Salt: A World History (London: Jonathan Cape, 2002).

The more sophisticated forms of humour evoke mixed, and sometimes contradictory, feelings; but whatever the mixture, it must contain one ingredient whose presence is indispensable: an impulse, however, faint, of aggression or apprehension. It may be manifested in the guise of malice, derision, the veiled cruelty of condescension, or merely as an absence of sympathy with the victim of the joke—a “momentary anaesthesia of the heart,” as Bergson put it. I propose to call this common ingredient the aggressive-defensive or self-asserting tendency. … In the subtler types of humour this tendency is so faint and discreet that only careful analysis will detect it, like the presence of salt in a well-prepared dish—which, however, would be tasteless without it.

—Arthur Koestler, The Act of Creation (London: Arkana, 1989).

Ice Machines.—Strong solutions of salt are used in some ice machines to carry cold from the refrigerator to the water to be frozen. Karsten found that water containing 28 percent. of salt resisted the crystallizing action of severe frost. Such water does not form ice at temperatures above –17.77ºC. It can be reduced therefore to –16.7ºC. and circulated at that temperature, around fresh water tanks, causing the fresh water to freeze into solid blocks of ice. In principle this is what is done in ice rinks; but the brine is a complex solution, containing, like the mother liquor of salt bay manufacture, magnesium chloride, and other highly deliquescent salts, which enhance the resistance of brine to cold. Such brine will take into circulation over 25 degrees of frost, so called. Something can also be gained by making the common salt solutions stronger than 28 percent., but it must be remembered that a 37.5 percent. solution is liable to crystallize into hydrate at –10ºC. to –15ºC. Salt is very largely used by German brewers, in the form of frigorific mixtures, for keeping down the temperature of their famous beer vaults. The consumption of salt for this purpose, in Germany, ranks next in importance to that used in chemistry, and above soap manufacture.

—James J. L. Ratton, A Hand-Book of Common Salt (Madras, India: Higginbotham and Company, 1882).

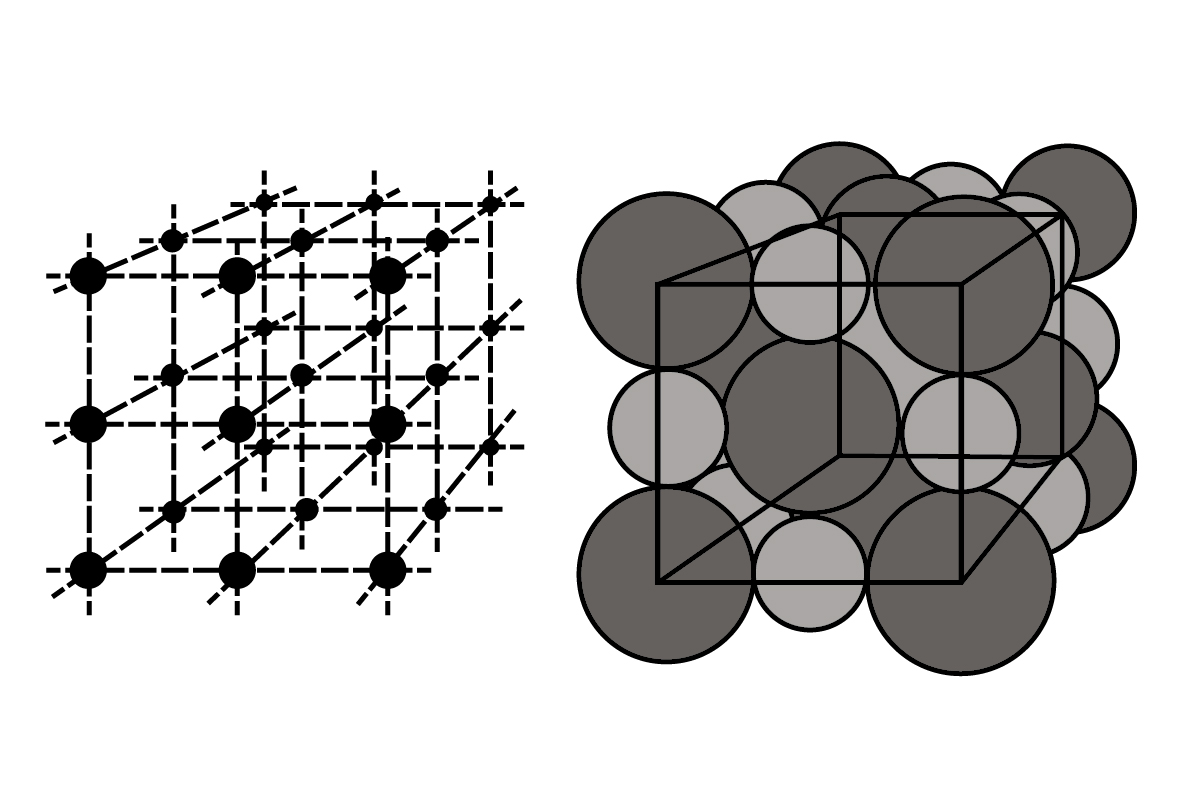

You can grow a salt crystal [above] by dissolving salt in a container of water until the water becomes saturated brine and will absorb no more salt. Tie a “seed” crystal of salt with cotton and suspend it in the brine.

The crystal will attract salt and gradually grow over a period of time. The longer you leave it the larger it will become.

paragraph

[In the Isle of Man] no person will go out on any material affair without taking some salt in their pockets, much less remove from one house to another, marry, put out a child, or take one to nurse, without salt being mutually exchanged; nay, though a poor person be almost famished in the streets, he will not accept any food you give him, unless you join salt to the rest of your benevolence.

—William Waldron, Description of the Isle of Man (Isle of Man, UK: Manx Society, 1725).

The principal consideration in this discussion of the 30 million years of evolution of the Hominoidea, is that diet was probably almost exclusively vegetarian during the first 25 million years. If the deductions on huntergatherer societies based on the Kalahari Bushmen and the Hadza are valid in relation to the hominids, then diet may have been predominantly vegetarian over the last five million years, though there was considerable variation in diet according to the prevailing climate and conditions. This is perhaps reflected by contemporary feral communities where diet may be predominantly vegetarian, as in some regions of Highland New Guinea or in the Yanomamö Indians of the Amazon Basin, or predominantly of animal products as, for example, with the Eskimos and the Maasai. … These vegetarian communities have very low rates of urinary sodium excretion. …

The environmental, dietetic and metabolic conditions which determined [the behaviour towards salt of herbivorous animals whose bodies retain sodium reserves and draw on them in times of deficiency through aldosterone secretion] could have operated on hominoids over a large part of their evolution. It follows that selection pressure would favour retention, and perhaps, elaboration of salt appetite mechanisms—both hedonic liking and the hunger with deficiency—which were developed at earlier stages of phylogeny. This may also have held for the elaboration of the physiological system of salt retention by aldosterone secretion, which has a multifactorial control that includes the assumption of upright posture. This selection pressure would have been ameliorated by meat-eating with the consequential obligatory sodium supply during the latter 2–3 million years of hominid evolution.

—Derek Denton, The Hunger for Salt: An Anthropological, Physiological and Medical Analysis (Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1982).

Those at sea often suffer from a deficiency of fresh water, and so I shall describe ways of combating the problem. Fleeces, spread round a ship, become damp by absorbing sea-spray: fresh water can then be squeezed out of the fleeces. Similarly, hollow balls let down into the sea in nets, or empty containers with their openings sealed, collect fresh water inside. On land salt water is turned into fresh by filtration through clay.

—Pliny the Elder, Natural History: A Selection, trans. John F. Healy (London: Penguin, 2004).

The story of the origin of the dynasty of the Saffaride Kaleefs, in the ninth century, is an illustration of the surpassing power of the covenant of salt. Laiss-el-Safar, or Laiss the coppersmith, was an obscure worker in brass and copper, in Khorassan, a province of Persia. His son Yakoob wrought for a time at his father’s trade, and then became a robber chieftain.

Having on one occasion found his way into the treasury of the palace of the governor, Nassar Seyar, who was then in control of Seiestan, Yakoob gathered jewels and costly stuffs, and was proceeding to carry them off. Striking his bare foot, in the darkness, against a hard and sharp substance on the floor of the room, he though it might be a jewel, and stooped to picked it up. Putting it to his tongue, to test it after the manner of lapidaries, he discovered that it was rock salt that he had tasted in the governor’s palace. At once he threw down his bale of stolen goods, and left the palace by the way he had entered.

The signs of attempted robbery being found the next morning, the governor caused a proclamation to be made throughout the city, that, if the man who had entered the treasury would make himself known at the palace, he should be pardoned, and should be shown marks of special favor. Yakoob accordingly presented himself at the palace, and freely told his story. The governor felt that a man who would hold thus sacred the covenant of salt could be depended on, and Yakoob was given a position near his person.

Step by step Yakoob went forward to power and honors, until he was chief ruler of Khorassan, and founder of the Saffaride dynasty in the Persian khaleefate. He died A.D. 878, and was succeeded by his brother, Omar II.

—H. Clay Trumbull, The Covenant of Salt, as Based on the Significance and Symbolism of Salt in Primitive Thought (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1899).

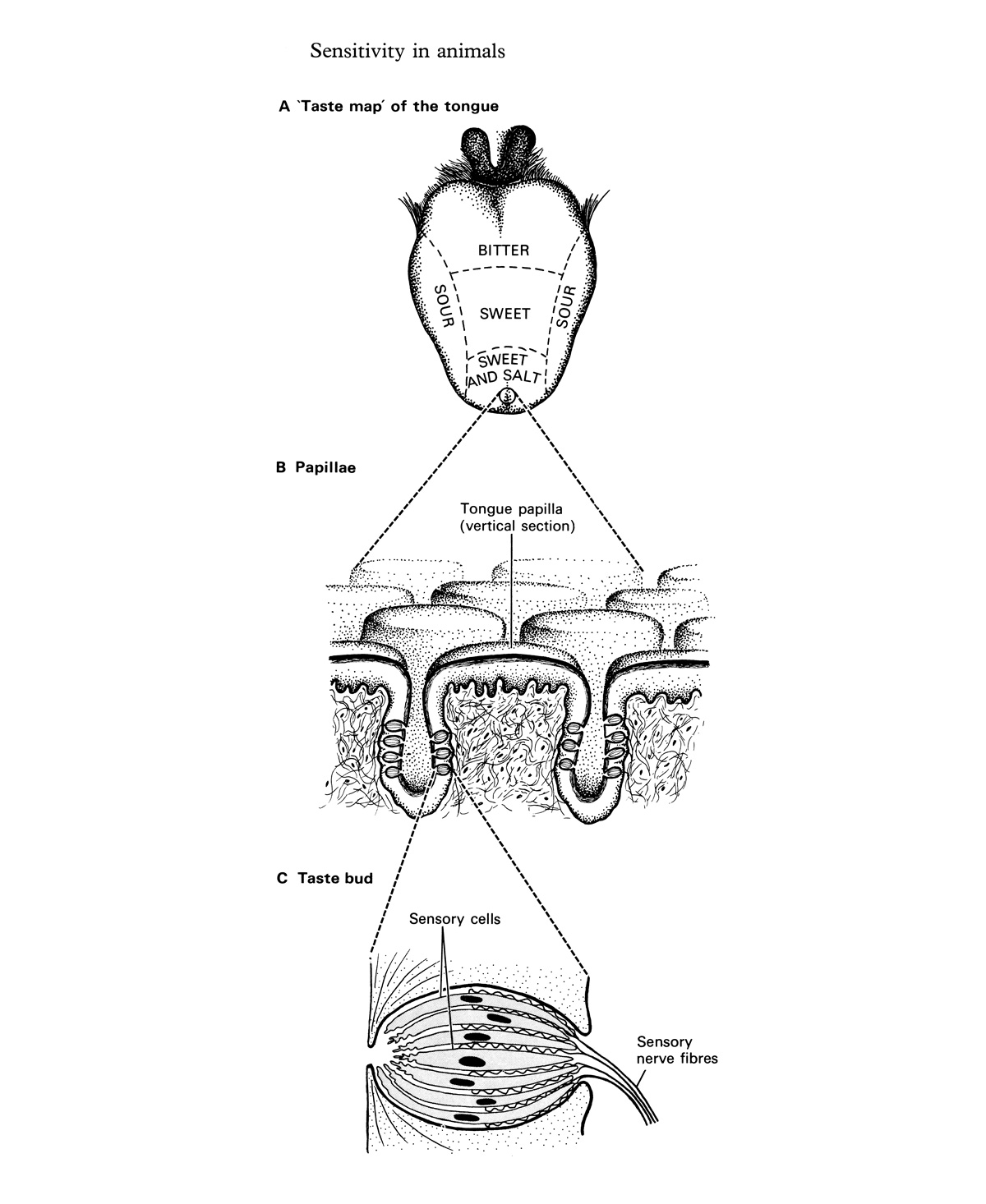

The issue of just how many taste buds an individual loses due to aging has been a major debate. Schieber (1992) states that several scientists estimated that a person could lose 20 to 60% of their taste buds after the age of 60. Schiffman (1977) mentioned that three scientists found that the average number of taste buds declines dramatically from 208 buds to 88 buds when a person reaches the age of 74. Research and debates over how many taste buds a person could lose continues.

A smaller number of taste buds may provide some insight as to why the elderly are only capable of recognizing the flavors of certain foods. The density in their taste buds, however, could provide even better insight to this problem. Researchers have speculated about whether or not a person’s taste bud density changes as he or she ages causing gradual changes in the ability to recognize certain flavors of foods. Miller (1988) found in one of his studies that taste bud density does not really diminish with age, but rather it stays at an equal level based on a person’s individual health. In this case, a person’s health could influence taste sensitivity. …

Although the elderly can lose a certain number of taste buds on their tongue, they may still be able to recognize certain flavors. Additives (such as salt, for example) can still be recognized fairly well by the elderly. Spitzer (1986) found that young men, aged 18 to 25 years old, had significantly lower salt thresholds than institutionalized and noninstitutionalized elderly men. This meant that the elderly subjects’ senses were able to create a response to the flavor of salt, but their response to salt was not as strong as the younger participants’ response.

—David Koepnick, “The Effect of Age on Taste,” 1999.

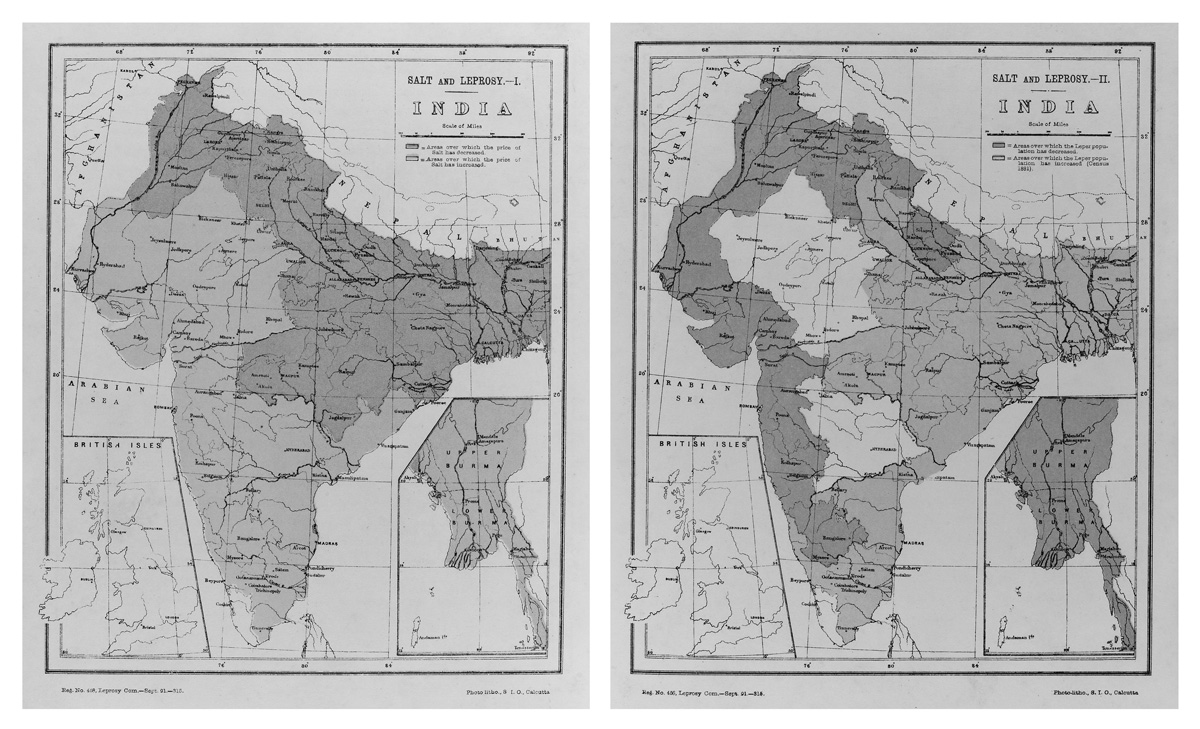

Salt and Leprosy II (right): The [darker] area establishes where the leprosy population has decreased, the other area where the leprosy population has increased. Maps from Leprosy in India: Report of the Leprosy Commission in India, 1890–91 (Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1892). Courtesy Wellcome Library.

Although the spilling of salt is supposed to bring ill-luck in general, its specific effect is to destroy friendship and to lead to quarrelling; more-over it brings ill-luck to the person to whom the salt falls as much as to the one who has spilt it. It acts, in other words, by disturbing the harmony of two people previously engaged in amicable intercourse. From what has been said [elsewhere in this essay] about the unconscious symbolism of eating in company it will be intelligible why the spilling of a vital substance at such a moment should be felt to be, somehow or other, a particularly unfortunate event. To the unconscious, from which the affective significance arises, it is the equivalent on one plane to “ejaculation praecox,” and on a more primitive plane to that form of infantile “accident” which psychoanalysis has shown to be genetically related to this unfortunate disorder.

—Ernest Jones, “The Symbolic Significance of Salt in Folklore and Superstition,” Essays in Applied Psycho-Analysis (London: The International Psycho-Analytical Press, 1923).

Acronym

Definition

S&P

Salt and Pepper

S&P

Save & Prosper [financial services group] [British]

S&P

Stake & Platform [technical drawings]

S&P

Standard & Poor’s Corp

S&P

Strategy & Policy Group [War Department] [World War II]

—Acronyms, Initialisms and Abbreviations Dictionary, ed. Jennifer Mossman (Detroit: Gale Research, 1995).

Implicasphere is an occasional publication. Past editions include “String,” “Mice,” “Folly” and “The Nose.” The first three issues were commissioned by PEER.

For orders and information email info@implicasphere.org.uk or visit www.implicasphere.org.uk [link defunct—Eds.].

Texts have been reproduced as they appear in original publications. Idiosyncrasies and house styles have been largely left intact. Considerable effort has been made to trace and contact copyright holders and to secure replies before publication, but this has not been possible in all instances, particularly with old material. We apologize for any inadvertent errors or omissions. If notified, the editors will endeavor to correct these at the earliest opportunity.

Implicasphere is edited by Cathy Haynes and Sally O’Reilly.

Supported by the Moose Foundation for the Arts and the Elephant Trust.

Thanks to Cabinet, New York.

Designed by Fraser Muggeridge studio.

Printed in an edition of 13,000 on Cyclus Offset (recycled).

© Implicasphere Ltd, London, 2006. Registered company no. 5757303.