Dead Troops Salute

Arthur Mole’s living photographs

Louis Kaplan

Almost a century ago and without the aid of any pixel-generating computer software, the itinerant photographer Arthur Mole (1889–1983) used his 11 x 14-inch view camera to stage a series of extraordinary mass photographic spectacles that choreographed living bodies into symbolic formations of religious and national community. In these mass ornaments, thousands of military troops and other groups were arranged artfully to form American patriotic symbols, emblems, and military insignia visible from a bird’s eye perspective. During World War I, these military formations came to serve as rallying points to support American involvement in the war and to ward off isolationist tendencies.

Arthur Mole’s formative religious ties in part explain what drew him to this spectacular type of photographic activity. Born in England, Mole immigrated to the United States at age twelve because his family followed the teachings of Dr. John Alexander Dowie, a Scottish-born Christian communal utopian who had established the city of Zion, Illinois, in 1901 in answer to the call of “Salvation, Holy Living, and Divine Healing.” If Dowie is credited with converting Arthur Mole to his way of Christian living, then Mole is responsible for converting Dowie into a living portrait in one of his first large-scale group productions. In this singular image, Mole’s mise-en-scène provides the faith-healer with a nimbus in the shape of the circular walking path of Zion Park.

The Moles arrived in 1901, around the time when Zion’s Christian Catholic Tabernacle—able to seat a Mole-like crowd of up to 10,000 people—was being built. The church was where Mole met John Thomas, the director of the choir, and later Mole’s choreographic collaborator. Thomas’s white-robed choirboys and the church congregation provided a readymade resource for the many religious bodies required to stage the first group portraits. Mole and Thomas would later return to their hometown in July 1920 to compose The Zion Shield.

This image, in which the ranks have closed around the sword and shield of an emblematic warrior figure constituted out of the religious faithful, foregrounds the militant and militaristic impulse embedded in this photo-practice, emerging as it does from a religious community grounded in fighting spirit and missionary zealotry.

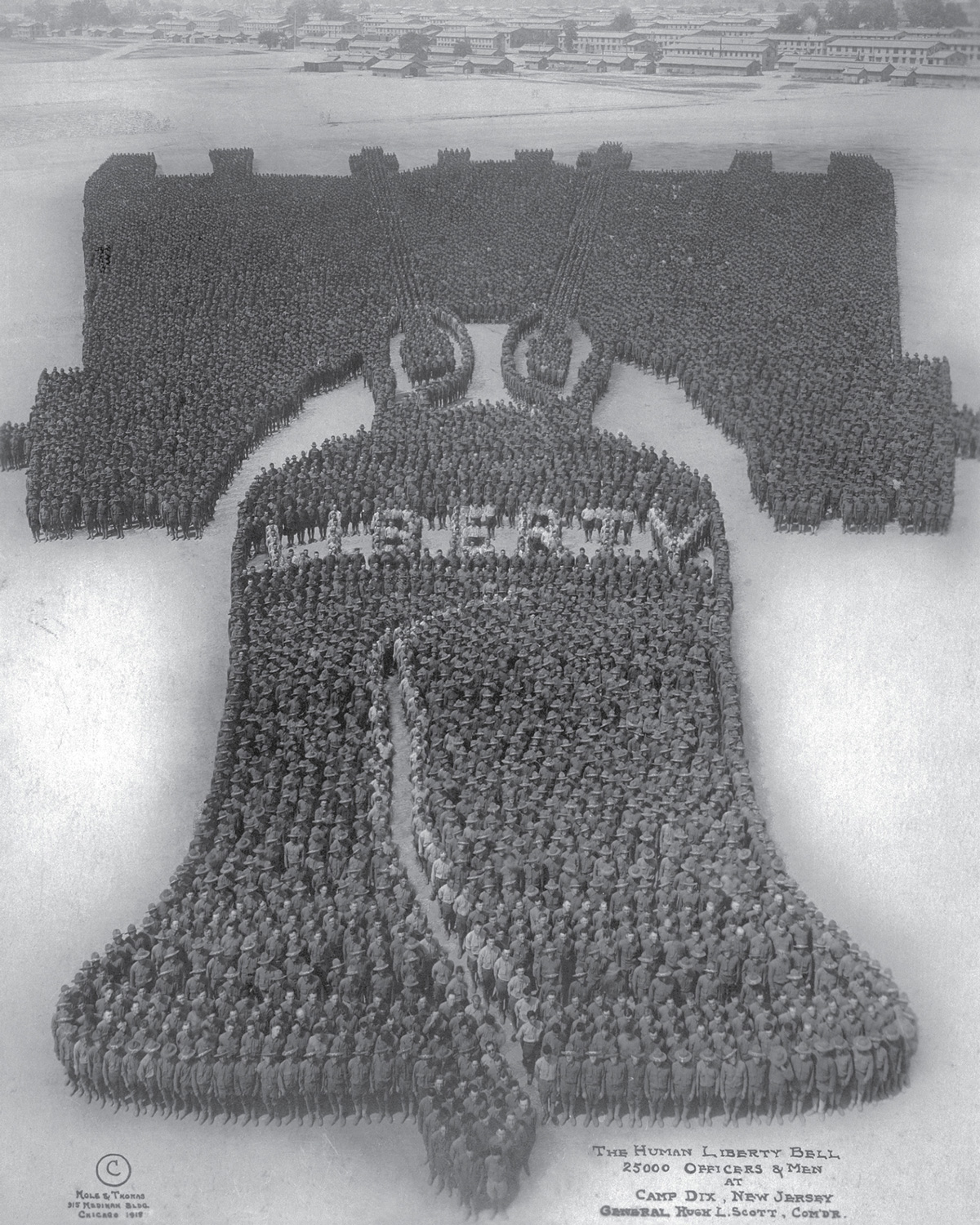

It was a short step from a militaristic image in the service of the Christian communal to spectacular images such as Human U.S. Shield, Living American Flag, and Living Statue of Liberty, each using the American military to affirm the bonds of national community. Mole and Thomas would spend a week or more on preparations for each photograph. This began by tracing the desired image on a ground-glass plate mounted on Mole’s camera. Using a megaphone, body language, and a long pole with a white flag tied to the end to point to the more remote areas where the bulk of the troops had to be stationed, Mole would then position his helpers on the field as they nailed the pattern to the ground with miles of lace edging. In this way, Mole also figured out the exact number of troops required. These steps were preliminary to the many hours required to assemble and position the troops on the day of shooting. For The Human Liberty Bell, Mole and Thomas traveled to Camp Dix, New Jersey (not far from the City of Brotherly Love), to assemble 25,000 troops in the shape of this national icon. The photo stages the Liberty Bell replete with its famous crack to increase its mimetic likeness and symbolic power. The human inscription of the word “LIBERTY” at the top of the bell signals an advance over the cue cards used in earlier images, such as the Zion Shield. Given that this patriotic symbol is composed of troops, the image delivers the platitude that American military involvement is always undertaken in defense of liberty.

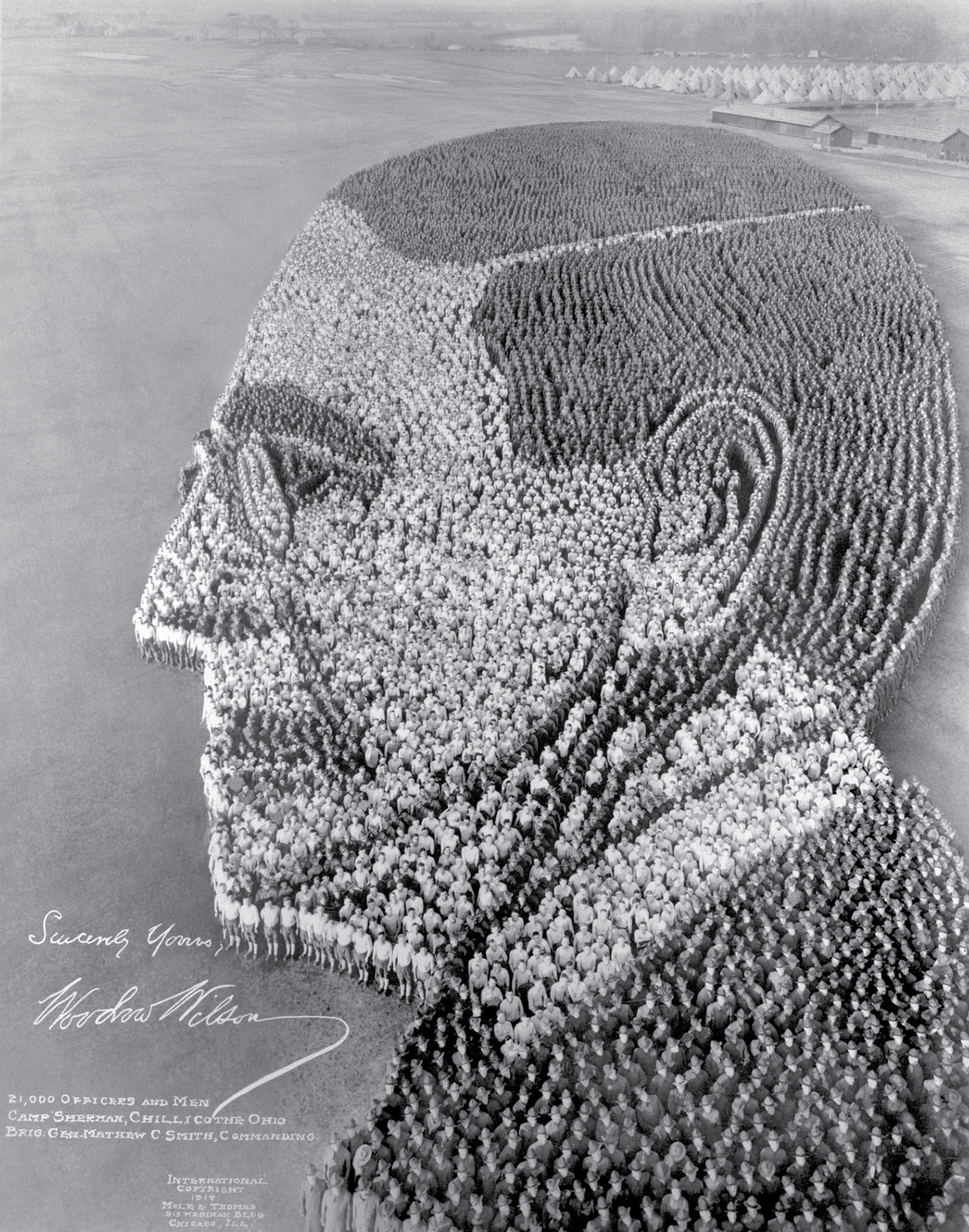

Living Portrait of President Woodrow Wilson, for which 21,000 troops assembled at Camp Sherman in Chillicothe, Ohio, in 1918, is the best-known of Mole’s photographs. The image is characteristic of Mole’s work in that it wavers between the compositional effect of the whole (i.e. a portrait of Woodrow Wilson) and the desire to focus upon the obscured individuals who constitute the image, thereby undermining the optical illusion of the totality to a degree. To call this image a portrait would be misleading because the subject of the representation is not so much the countenance of Woodrow Wilson as what he represents and symbolizes. As a literal figurehead, Wilson represents the paternal function of the Fatherland, including the power that accrues to the Presidential office and to the commander of the armed forces. Wilson has signed the image with the personal salutation “Sincerely Yours,” the flourish of this personal “signature effect” working to mask the status of Wilson as the impersonal representative of the American symbolic order.

The most intriguing thing about these images is that Mole called them “living photographs.” From the photographer’s perspective, the emblems are brought to life by means of the living soldiers who embody them. But one can also look at these images from the opposite perspective: we deaden the human beings into form and formation by making them into emblems. The emblem only comes into focus when the living element drops out of the group portrait in these spectacular optical illusions. This total subjection of the individual to the symbolic order also exposes the fascistic tendency inherent in such images. Mole’s “living photographs” thinly disguise the forces of death that in fact adhere to all community.

In The Inoperative Community, the French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy designates World War I as a turning point in the thinking of community in Western societies, as a time when the meaning of community became inscribed in terms of the “community of death.” From this perspective, Mole’s images are realized at a critical historical juncture. His living photographs expose this community of death and seek to make meaning out of it via patriotism’s proud symbols and grand gestures. But Nancy also suggests that there is something absurd in this enterprise—of constructing meaning out of death, out of that which delimits the death of meaning. Arthur Mole’s living photographs remain compelling records of this paradoxical enterprise.

Louis Kaplan is associate professor of history and theory of photography and new media at the University of Toronto and director of the Institute of Communication and Culture at the University of Toronto at Mississauga. He is the author of American Exposures: Photography and Community in the Twentieth Century (University of Minnesota Press, 2005), Laszlo Moholy-Nagy: Biographical Writings (Duke University Press, 1995), and co-author of a book on Gumby. He is currently working on projects devoted to the inventor of spirit photography William Mumler (with the University of Minnesota Press) and on the California countercultural artist, Wallace Berman. For more information, visit www.utm.utoronto.ca/dvs/louis-kaplan.