Protean Fakirs

Indian magic’s new superstar

Shreeyash Palshikar

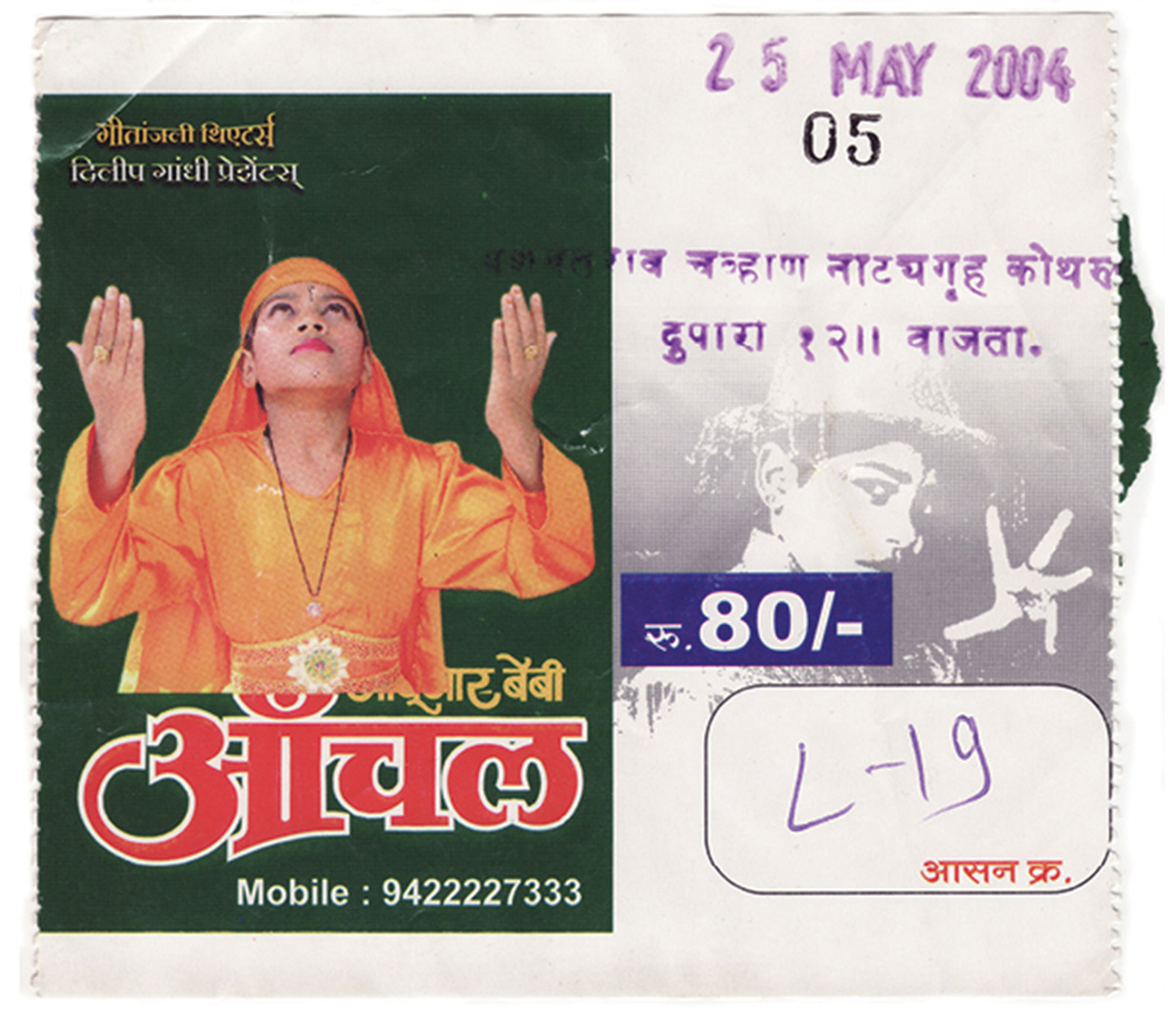

During the afternoon of 25 May 2004, I sat among an audience of around three hundred, preparing to witness the immolation of a young Indian woman. She lay supine in a shallow wooden box, her cremator-to-be standing slightly to her left. Before setting the girl alight, the latter reminded the audience that every year in India, many young women are likewise burnt alive by their relatives following dowry disputes,[1] and asked them to “promise that they would never give, ask for, or take dowry.” She then lit the fire, apparently incinerating the young woman in the box, which issued forth flame and smoke for several minutes. The first half of the show ended there; the young female assistant was not shown to be happily alive.

The cremator-magician, Jadugar “Baby Anchal” Kumawat, was a young girl herself, just thirteen years old, at the time of this performance at a theater in a suburb of Pune, India. Performing magic since the age of five, Kumawat had by 2004 developed a show in excess of three hours long, complete with illusions, animals, and multiple male and female assistants; she claims now to have completed more than four thousand performances.[2] Newspaper advertisements and billboards proclaim her to be “India’s youngest magician,” a dubious title claimed by many Indian performers, including, decades before, my own uncle. Her promotional materials show a young girl wearing a sequined outfit and a glittering top hat festooned with strings of colored beads, her hands striking a magical gesture with fingers splayed wide apart, reminiscent of Indian fakirs familiar to the Western imagination.

Kumawat is a self-assured performer, with a charisma and energy that many magicians twice her age would envy. Her father, Girdhilal Kumawat, introduced Anchal to magic as a young child and taught her the basics of the art personally. When she showed an early aptitude, he was quick to arrange her first show in Udaipur in 1997. Her family now travels with her whenever she performs, assisting with the show, and her seven-year-old brother even dances as part of the troupe. While in the West the emergence of a precocious child performer might trigger institutional suspicion and prurient media interest, in 2004 Kumawat was awarded one of the Government of India’s Exceptional Child awards, and in August 2006, the Indian Ministry of Human Resources sent her and her family as Indian cultural ambassadors to perform in Mongolia.

Kumawat is not the only professional female magician performing in India, but in the male-dominated magic profession, she is a conspicuous and provocative figure.[3] In a country where national unity is often the casualty of religious division, Kumawat addresses both topics within her act, the former with a routine involving flags, the latter using a pan-religious white dove of peace. Following her cremation act, when she tells her audiences about dowry deaths, she is talking about an issue that, as a young Indian woman, could very well affect her directly some day.

In Net of Magic: Wonders and Deceptions in India, Lee Siegel noted this secularized socio-political component within contemporary Indian magic, which stands in contrast to its more ostentatious and commodified mystical iconography. For example, among the numerous street performers of Delhi’s Shadipur Depot during the mid 1980s, Siegel encountered an “industrial magician” employed by a bank to promote their services in villages, who used a vanishing coin trick to discourage the hiding or burying of savings. UNICEF employed charismatic local performer B. Kamesh to perform with a small “inexhaustible” vessel to promote the use of breast milk, while magician Chand Pasha performed with condoms as part of a family planning program. More recently, magician Mhelly of Bombay has used magic to promote a variety of corporate products from toothpaste to airlines, whilst Kerala’s top stage magician, Prof. Gopinath Muthukad, presented a show that promotes Indian unity by referencing Ghandi’s yatra (journey), an act that he has performed all across India, and even in South Africa.

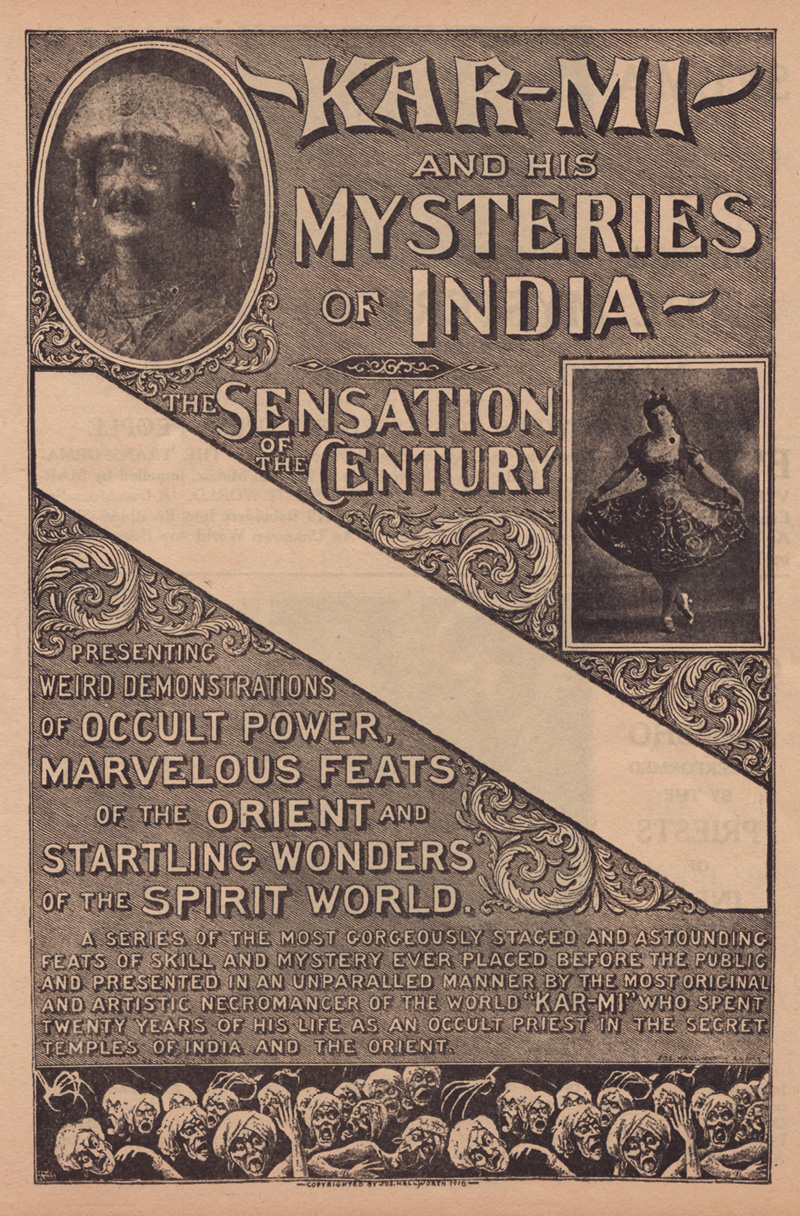

The genealogy of the character of the contemporary Indian magician is complex. While its roots lie in generations of indigenous street and court performers, its current, recognizable face—bejeweled turban headdress, flowing robes, and garish palette—owes more to knowing reconfigurations of earlier Western appropriations. From the 1820s, Indian magicians such as Khai Khan Kruse and Ramo Samee performed in England, with the first Indian performers appearing in the United States at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where a young Harry Houdini learned the Indian needle trick. From the late 1800s onwards, non-Indians also took on the character of the “Indian magician” on Western stages, with performers such as the White Mahatma (Samri Baldwin, US, 1848–1924), Kar-Mi (Joseph B. Hallworth, US, 1872–1957), and even occasional-magician Charles Dickens, simply putting on “Indian clothes” to present their acts.[4] Observing the popularity of these appropriations, and noting their technical content, indigenous Indian magicians began to adjust their own image to meet the expectations of visiting (and paying) Western audiences, most notably by providing performances of the Indian Rope Trick, a hoax that had been created by magician and journalist John E. Wilkie from his desk at the Chicago Tribune in the early 1880s.[5] Another group who responded to the protean stereotype of the exotic Indian fakir were African American performers, some of whom disguised themselves as Indians in order to play the legitimate vaudeville circuits from which they were otherwise excluded.[6] Prince Jovedah de Rajah, whose real name was Arthur Dowling, continued to play an Indian magician offstage, allowing him to live a life unimaginable for an African American in the US in the 1920s—married to a white woman, and residing in hoteliered luxury.

Kumawat’s audiences are witnessing, therefore, a performer whose iconography is the result of a symbiotic exchange of imaginations and economies between India and the West throughout their respective, interwoven histories. Her sequined top hat tips itself to the West, the origin of most of her illusions, yet her show addresses the localized concerns of Indian audiences, its Hindi patter and aesthetic circumventing long-evolved stereotypes and pointing the way for more individuated performers. The evening comes to an end with another violent bodily incursion, this time with Baby Anchal herself the victim of a buzz-saw illusion. Despite melodramatic self-regret from her stage assistants, the expected restoration again does not take place. Instead, the audience is assured that a lasting memory can be obtained, for a small price, in the foyer upon departure: a photograph taken standing beside the finally restored and smiling magician.

- See Rani Jethmalani, ed., Kali’s Yug: Empowerment, Law, and Dowry Deaths (New Delhi: Har-Anand Publications, 1995); Ammu Joseph and Kalpana Sharma, eds., Whose News?: The Media and Women’s Issues (New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1994).

- Interview with Dilip Gandhi (producer), Jaduguar Anchal Kumawat, and Girdhilal Kumawat, 11 March 2007.

- Maneka Sorcar, granddaughter of the legendary P. C. Sorcar, has begun to perform on her own, and another young performer, Zenia Bhumgara, draws large audiences with her dove act.

- Sarah Dadswell, “Jugglers, Fakirs, and Jaduwallahs: Indian Magicians and the British Stage,” New Theatre Quarterly, vol. 23, no. 1, February 2007, pp. 3–24.

- Peter Lamont, The Rise of the Indian Rope Trick: How a Spectacular Hoax Became History (London: Little, Brown, 2004).

- Jim Magus, Magical Heroes: The Lives and Legends of Great African-American Magicians (self-published, circa 1995).

Shreeyash Palshikar, a scholar and a performer of Indian magic, is completing a Ph.D. in the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. He currently lives in London where he is creating a new theater show that blends Indian and Western magic. For more information, visit www.palshikar.com.