Bashford’s Grotto

Chadwick Dalton

Torrent Chadwick and Chadwick Dalton are members of a prominent and ancient family of sea captains, dandies, amateur historians, and armor collectors on both sides of the Atlantic. Over the past decade, however, the financial pressures of maintaining the Chadwicks’ vast archives have forced the family to lend elements for public exhibitions, a task with which Jimbo Blachly and I have been contracted to assist them. During the summer of 2006, Blachly and I installed an exhibition of Chadwick and Dalton’s research into the life of their ancestor’s neighbor, Bashford Dean, at the Wave Hill cultural center, a converted Hudson River mansion and garden. When Cabinet learned of the Chadwicks’ discovery—that a volcano built by Dean, with a pyrotechnics laboratory and howitzer inside, can be counted among America’s least known (and most dangerous) mountains—they asked us to condense the following didactic text composed by Chadwick Dalton, in consultation with Torrent Chadwick, for the exhibition at Wave Hill.

—Lytle Shaw

The dashing, multitalented, and mysterious Bashford Dean (1867–1928) lived at Wave Hill from 1909 until his death. In addition to co-founding Columbia University’s Department of Zoology, Dean was the only person ever to hold simultaneous curatorial positions at the Metropolitan Museum (arms and armor) and the Museum of Natural History (reptiles and fishes). Perhaps the foremost arms and armor expert of his day, Dean took the atypical step, while only leasing Wave Hill, of hiring the architect Dwight James Baum to design, first, a period hall for his world-renowned armor collection, and later, a volcanic grotto—the now-vanished jewel of the ever-generative Wave Hill landscape.

During the summers of 1870 and 1871, the Manhattan-based family of Theodore Roosevelt had rented the property as a way to give the adolescent president-to-be exposure to the mansion’s carefully pruned horticulture. While Parisian anarchists pried up cobblestones and turned their city into a temporary commune, Teddy strolled the Wave Hill grounds in rapture, establishing a lifelong bond that was later monumentalized in the National Park System, with its larger, more rugged Wave Hills—Yosemite, Glacier, Yellowstone, and the Grand Tetons. If, however, Wave Hill was not only a landscape, but also an exemplary shaper of other terrains, then the evidence of the howitzer-filled volcano Torrent and I discovered may give us pause to consider a more somber form of landscape, indeed a kind of grisly Badlands, stemming equally from this site.

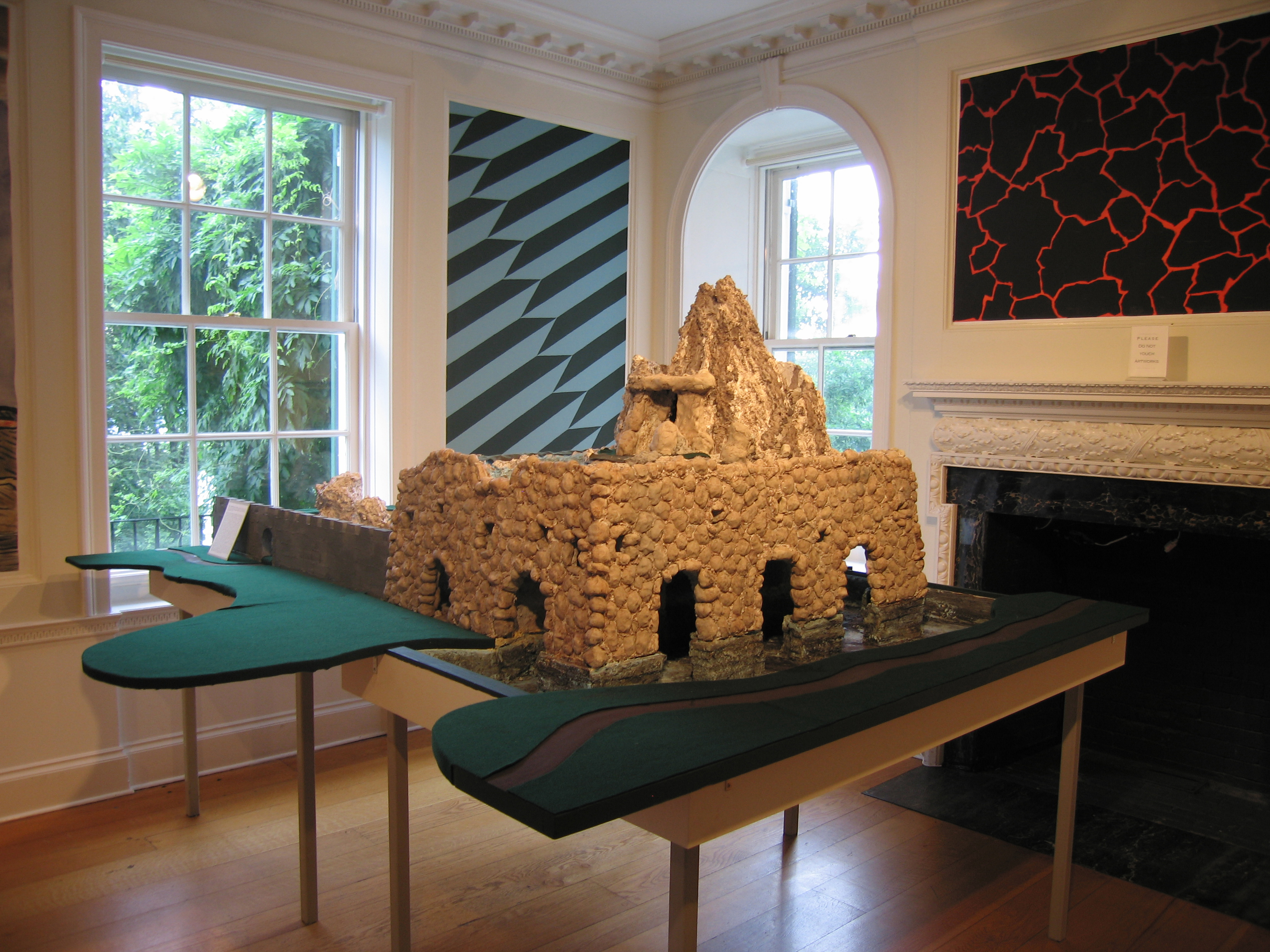

It was, in truth, former resident Mark Twain’s comment in a letter about Wave Hill providing “the noblest roaring blasts … I have ever known on land” that began our inquiry. Torrent and I had just come back from bird-watching at our own estate, Chadwick Manor. Torrent had been reading Twain’s Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. After reciting to me in his poor reading voice the scene in which medieval knights battle a modernized army with Gatling guns, and linking this dilemma to our ancestors’ neighbor, Bashford Dean, Torrent’s features clouded into that unmistakable grimace that suggests the presence of what he calls an “idea.” “‘Roaring blasts,’ Dalton, what on earth could Twain have meant?” “Touché, Torrent,” I added without missing a beat, “Being poor zoologists, Twain scholars believe this refers to the bird. But blasts aren’t found north of the Mason-Dixon line.” Following this anomaly up in our library, we discovered the context of Twain’s remark, which continues: “Model of chivalry or not, my nerves curse that infernal Dean of explosions.” Torrent himself came distinctly to resemble a projectile upon this revelation, which showed Twain gesturing not at some feeble birdsong, but rather at an ambiguous pyrotechnic occurrence on a site only minutes from our estate. It was this that led us, under cover of night, to the covert archaeological excavations on the Wave Hill grounds that yielded both model and charred proof of the volcano itself.

The precedent for Dean’s volcano may have been a folly on the estate of Dean’s wife, Mary Dyckman, which could, through pyrotechnics inserted in its base, simulate the explosion of Vesuvius that had so gripped Enlightenment scientists and aesthetes alike. Avid readers of Sir William Hamilton’s treatise on the Vesuvius eruption, the Dyckmans would have used their folly both to contemplate the sublime powers of nature—in carefully staged explosions—and to celebrate the Volcanist critique of the Neptunists. For while Neptunists advocated an orderly world emerging from the sea according to a creator’s carefully planned stages, the Volcanists saw the earth as the result of inspiring “outbursts” of activity, a position that not only circumvented a creator, but also took the never-ending chain of sudden violent eruptions as the generative force of history, geologic and social.

Volcanists would have gasped in horror, however, at the sudden catastrophe of World War I. Pressed into service as a consultant for the Allies, Dean drew on his studies of medieval armor—later published in his treatise, Helmets and Body Armor in Modern Warfare. In a transformation that was not missed on Ian Fleming as he scripted the early James Bond novels, Dean turned the armor shop at the Metropolitan Museum into a helmet production and testing lab. But when his proposed helmet was ultimately rejected, Dean resolved to build and test it himself at higher, volcanic temperatures. As Dean sought a site, he discovered that Wave Hill’s geology was a gypsum vein every bit as remarkable as the massive talus slopes of the Palisades across the Hudson, which had drawn the scientific attention of Huxley and Darwin. Gypsum, moreover, could be sculpted and painted to resemble basalt, which the Volcanists viewed as the very embodiment of sudden but enlightened change.

Attracted as he was to armor, Dean was at last prevailed upon by his close friend Rear Admiral Chadwick that defensive advances did not win wars. Turning his volcanic forge to an offensive end, Dean was thus forced to make peace with the bane of his mature life—that crass force that had forever banished armor and its chivalric world, had leveled lord and soldier, and rendered obsolete the majestic architectural form of the castle. Yes, gunpowder. During thunderstorms Dean would fire his volcano-encased howitzer into the rock faces of the palisades, employing a squad of neighborhood boys (who at other times engaged in mock jousts on his lawn) to row across the river, hike up into the rock face, and take precise measurements of the impact. By correcting minor errors in previous artillerists—Frenchman Jean Gribeauval, and Englishmen Whitworth and Armstrong—Dean developed a cannon that, camouflaged beneath a craggy, forlorn mountainscape that might have drawn out the sketchbooks of the more artistically bent German foot soldiers like Paul Klee, was in reality a modern instrument of destruction comparable in force and accuracy with the famed 420-mm steel guns of Alfred Krupp.

The story of Dean’s volcano is an all-too-American fable of declining idealism, of the settler grandfather’s noble aspirations gone awry in later generations. For though Dean too subscribed nominally to a Volcanist position—he was a Darwinian after all—the explosions he celebrated at Wave Hill were not the wild diremptions of order that gave sublime pleasure to his ancestors, but rather the planned and measured coruscation that would, by instrumental reason, land the projectile as the dominant force in modern warfare, and thus attach a terrible purpose to the great purposiveness that had held his Enlightenment forbearers in rapt fascination.

For an exchange between Professor Maiken Umbach and Torrent Chadwick concerning “Bashford's Grotto,” see here.