Bone Play

The anatomist’s games

Eva Åhrén and Michael Sappol

Anatomy has been a controversial practice ever since Andreas Vesalius and his colleagues founded the modern anatomical tradition in the mid-sixteenth century. There was a great stigma attached to anatomical dissection and, even worse, the display of human remains. The public regarded such activities as a deliberate desecration of the dead, and this response disputed the central premise of anatomical science. Anatomists claimed to “shine a light on the interior of the body,” and dissection became the key method through which physicians and surgeons produced scientific knowledge of the body, as well as the privileged ritual that inducted students into the medical profession. Anatomy was praised as one of the exemplary sciences of the Enlightenment.

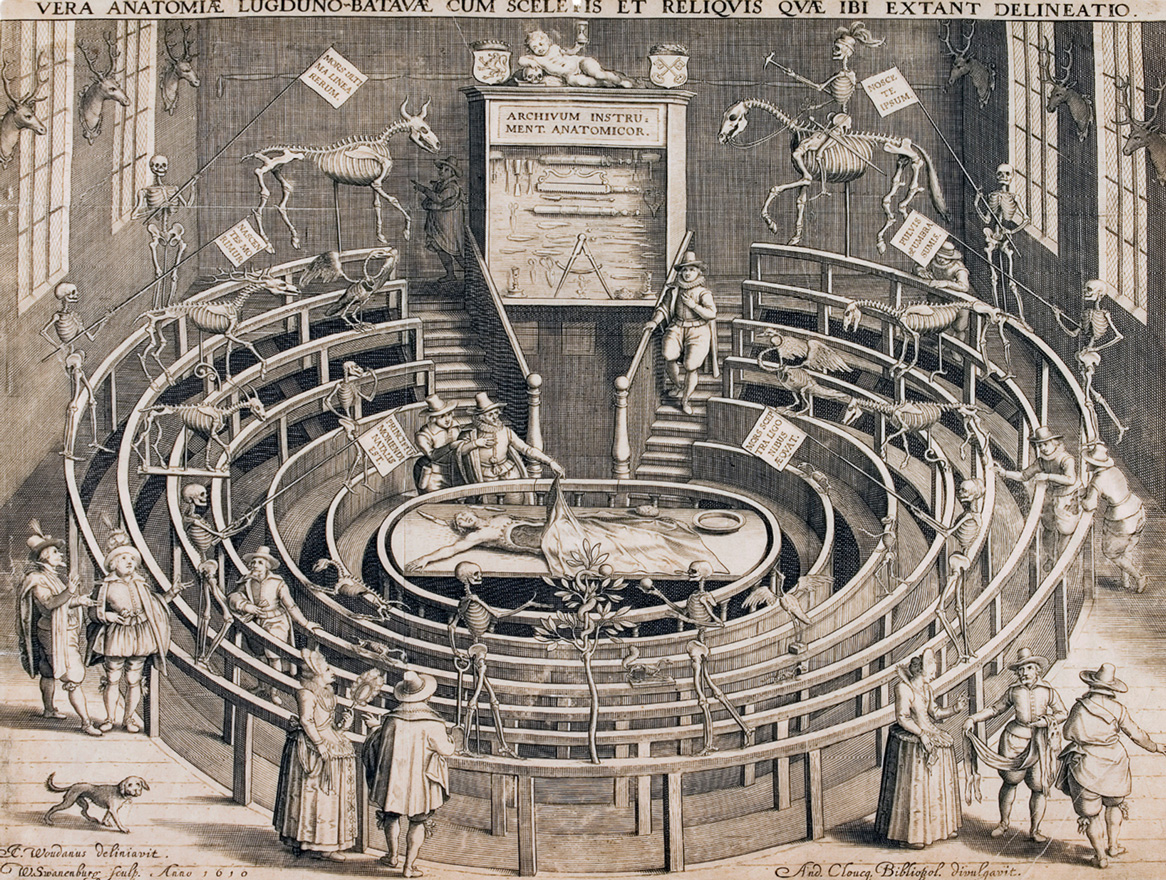

But anatomy was also a death cult. It invited us to know ourselves through the study and appropriation of the dead. And asked its practitioners to put aside any qualms about dealing with the dead, to enthusiastically mine their cadavers and search for knowledge within them, with the same kind of relish that prospectors searched for gold. Old anatomy halls often bear mottos such as “hic locus est ubi mors gaudet succurrere vitae” (“this is the place where death rejoices in aiding life“) and “gnosce te ipsum” (“know thyself”). And the study of bones, the stuff of which we are built, produced the profoundest knowledge of what it is to be human. In the old anatomy theater of Leiden, skeletons, holding flags with mottos such as these, were mounted in a kind of parade, at once playful and awe-inspiring, around the perimeter. Obviously, the anatomical practice of cutting into dead bodies and laying bare the bones was more than a scientific quest to discern the objective facts of the human body.

The medical profession in general, and anatomists in particular, used the privilege to handle human bones as a kind of social power play. Before the age of body donation, which commenced in the US around 1950, the cadaver was an unprotected human body. The remains of convicted criminals and the indigent poor—people who had few social or political resources to defend their bodies in death—supplied the dissecting table. In the sanctity of the anatomy room, the medical student could work his will, and, for the most part, had little to fear from anyone looking over his shoulder (except for the professor, guardian of the anatomical cult).

But death is powerful. Anatomical dissection has a grotesque and provoking character: it has to be tamed, domesticated. Bones and gore threaten the purity and disinterestedness of science, the clinical detachment which came to be medicine’s defining professional ideal. Medical educators coped by setting up rules of behavior in the anatomy hall. They demanded cleanliness and decorum, and even, sometimes, respect for the dead. But over and over again, such rules went unheeded. So what went on in the anatomy halls? What did medical students do?

They played. With the dead. And as the flesh was gradually sheared away, they played especially with the bones, the skeleton. Bone play was, in part, a carnivalesque response to the professional requirement that the medical student overcome personal sensibilities. Like everyone else, medical students were brought up to respect and fear the dead body. Overcoming this deeply ingrained response can be difficult. For some students, the first class in anatomy is a crisis, a test of suitability for a medical vocation. Some break down, suffer pangs of nausea, disgust. Others warm to the task quickly, become almost addicted. In either case, the dissecting experience created, and was partly designed to create, a sense of camaraderie around the shared experience of anatomizing the dead, which was the shared secret of the cult of professional medicine, a ritual of mastery over death. It was a ritual that was accompanied by an impulse to dramatize and fool around. In a picture from the early 1900s, Danish surgery students mock the teaching situation by dressing up a skeleton in a white frock and putting a bone saw in its hand and a cigarette in its mouth. Before modern ventilation and refrigeration, it was common to smoke in dissection halls, as a way to disguise and cope with the stench. The fraternity of dissectors, which initially excluded women, was also a fraternity of smokers.

In late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America, such photographs became a subgenre of photography. Medical students loved to ham it up before the camera, with partly dissected cadavers or skeletons, the remains often arranged in an “action” pose. Such photographs—reproduced in medical school yearbooks, novelty postcards, and souvenir placards—celebrated and mocked the medical college and human experience, and showed a playful, sometimes sadistic, indifference to any cultural, religious, or moral requirement to treat the dead with respect and honor. The cadaver and the skeleton were medical property.

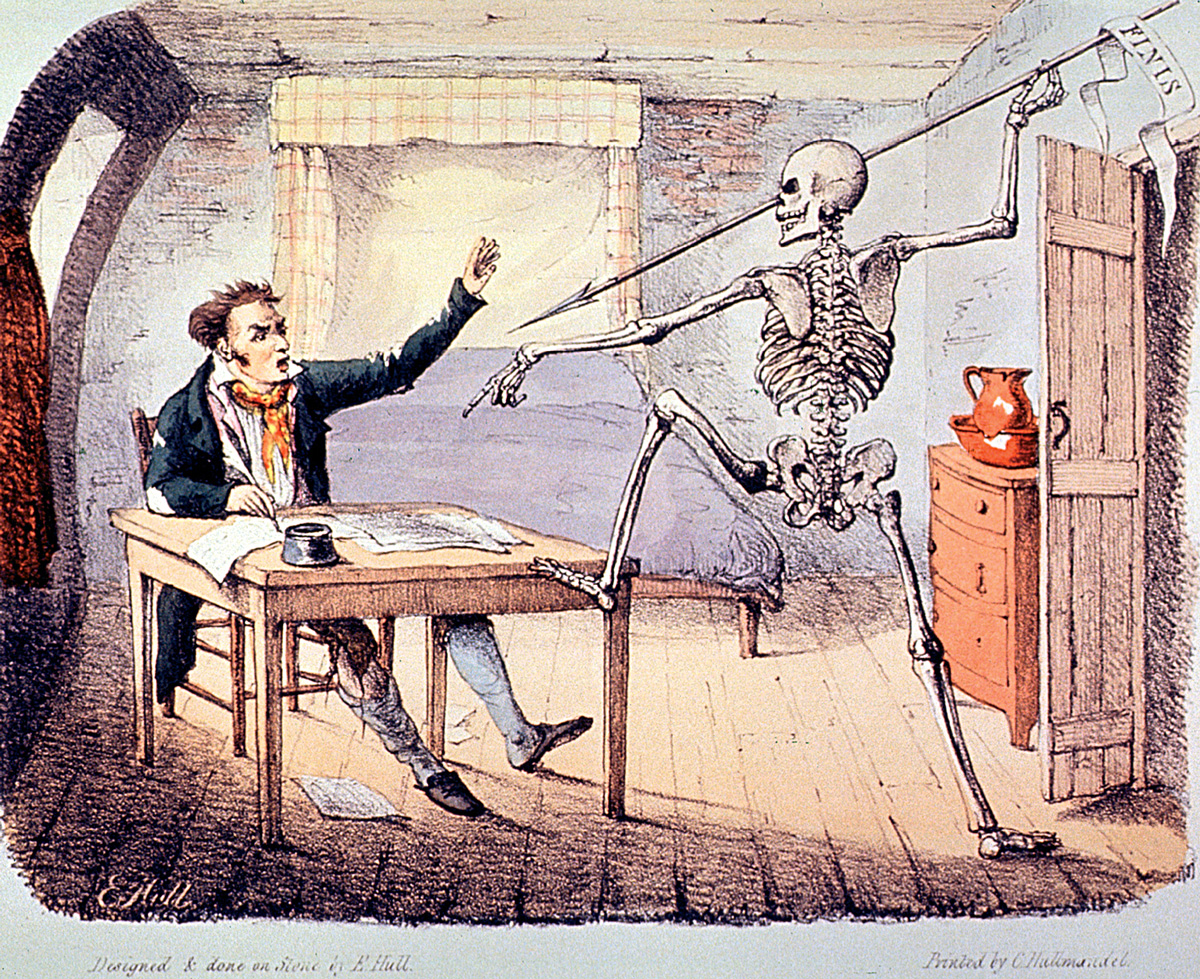

Anatomy students, of course, were not the only ones to make death icons, to take visual pleasure in death. Bones proliferate in the realm of representation. Bony tomb sculptures, paintings, and funerary objects could curse enemies, or warn the living to repent of their evil and respect ancestors. During the era of the Black Death and for centuries thereafter, satirical prints and engravings featured skeletons stepping lively in a danse macabre that mocked the living or sadistically disrupted the everyday life of mortals. In the 1970s and 1980s, heavy metal bands featured skulls and bones on album covers. The Aztecs and other Central American civilizations that were morbidly obsessed with death created many skull and bone artifacts, some out of stone, some out of war captives and ritual victims.

Representations of the human skeleton are, however, probably more ubiquitous in present-day Western culture. Whether visiting art galleries or going to the mall, it’s hard to avoid skulls and ribcages: you see them in art installations, on posters, T-shirts, umbrellas, and even baby bibs. A time-traveler from the seventeenth century would be stunned: twenty-first-century people seem to ponder their own mortality and the vanity of life more obsessively than early modern people who meditated on such things with the help of still lives or figurines. Or do we? Maybe the abundance of manufactured bones have a kind of smoke-screen effect that helps us not to think about death. By sequestering death in the realm of art, pop culture, and kitsch, maybe we hope to attenuate the certain prospect of our impending mortality: Death becomes just another disposable consumer object, or conversely just another collectible. Thus accessorized, we no longer get good representational service out of the skeleton as an inner self, which traditionally negated our individuality and pointed to our common identity and fate: there’s no possibility of transgression. If so, then the skeleton is gasping its last breath. Bone play is not as much fun as it used to be.

Eva Åhrén is a historian working on the cultural and scientific history of anatomy and the body. Her current research project is on displays, spaces, specimens, and models in the anatomy museum of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden.

Michael Sappol is curator-historian at the National Library of Medicine (National Institutes of Health), Bethesda, Maryland, and author of A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton University Press, 2002) and Dream Anatomy (GPO, 2006). In 2006, he curated “Visible Proofs,” an exhibition on the history of forensic medicine, and in 2007 curated “The Cartoon Medicine Show,” a program of animated medical cartoons from the 1920s to the 1960s. His current work focuses on modernist medical illustration from the 1920s to the 1950s and on the history of medical films.