A Buried History of Paleontology

The remains of Waterhouse Hawkins

Brian Selznick and David Serlin

Fossils, the remains of long-dead organisms that once walked the earth or swam its seas, form the skeletal structure of the science of paleontology. Humans certainly contemplated and collected fossils long before the term paleontology was ever coined: bones have been used to prove the existence of everything from dragons to Cyclops to a race of gigantic men. But it wasn’t until the mid-eighteenth century that people began to understand what fossils actually were. British naturalists William Buckland and Richard Owen, following the work of French zoologist and paleontologist Georges Cuvier, applied the techniques of comparative anatomy in an attempt to determine what kinds of creatures would have left behind such enigmatic fossilized bones. Among Owen’s many scientific accomplishments, he is responsible for coining the word dinosauria (“terrible lizard”).

Yet for all of the available examples of fossilized bones, no one in the early world of paleontology had ever discovered a complete and intact fossilized skeleton. This lack of information forced Owen to extrapolate about dinosaurs’ size and shape from examples of teeth, rib bones, and spikes, and to make educated guesses about their position in dinosaurs’ unique morphology. In the late 1840s, Owen commissioned Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, a British artist and amateur scientist, to build the first life-size sculptures of dinosaurs based on speculations by Owen and Gideon Mantell, the British paleontologist who had done the first work on Iguanodons. Hawkins created them for the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park, and after the close of the exhibition helped to transport them in 1852 to Sydenham, a suburb south of London, where an enlarged version of the Crystal Palace was rebuilt on what became Crystal Palace Park. The dinosaur sculptures were made of iron skeletons and fashioned from bricks and concrete, a hybrid form that evoked both the prefabricated steel-and-glass structures that comprised the original Crystal Palace as well as the brick and mortar of traditional English architecture.

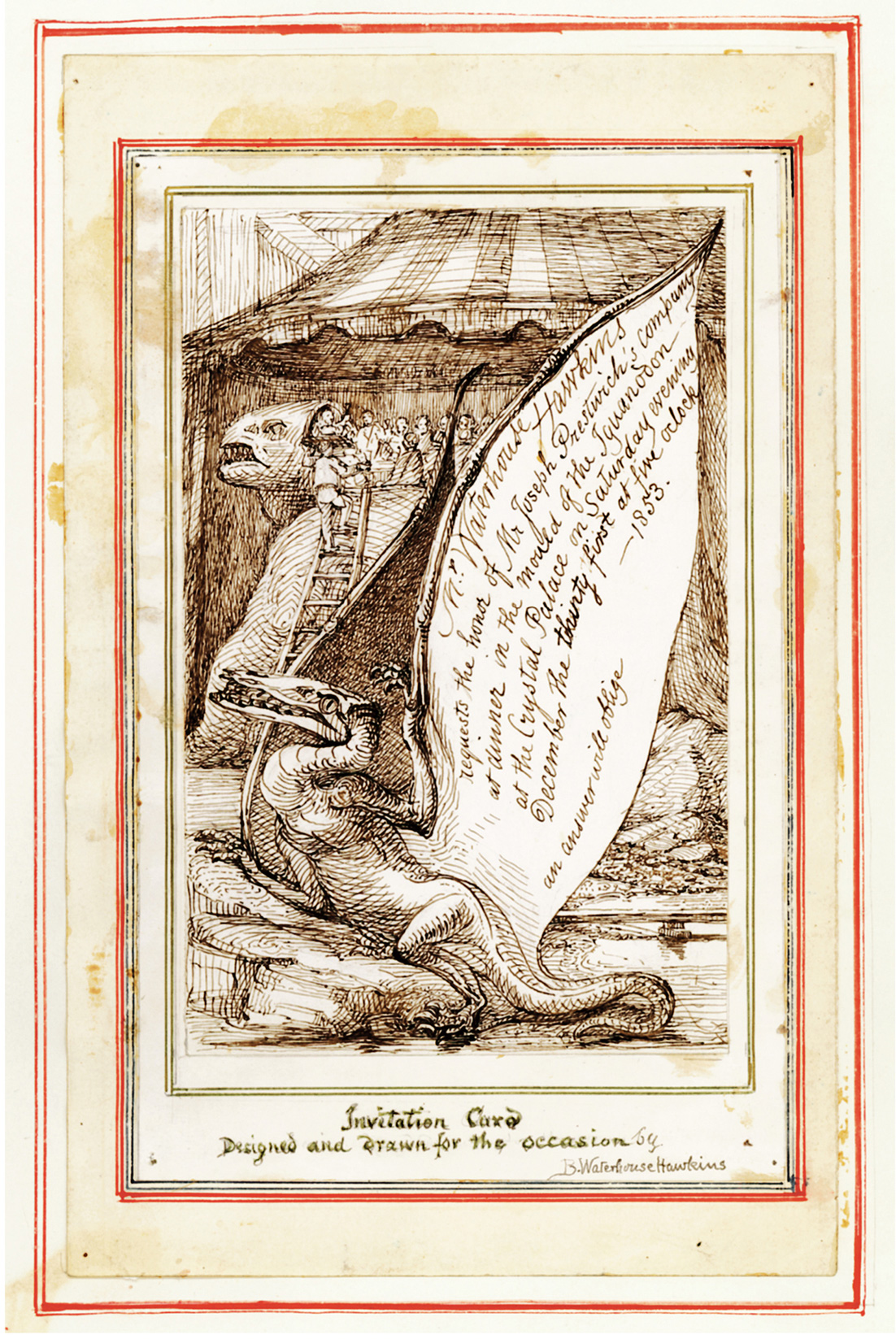

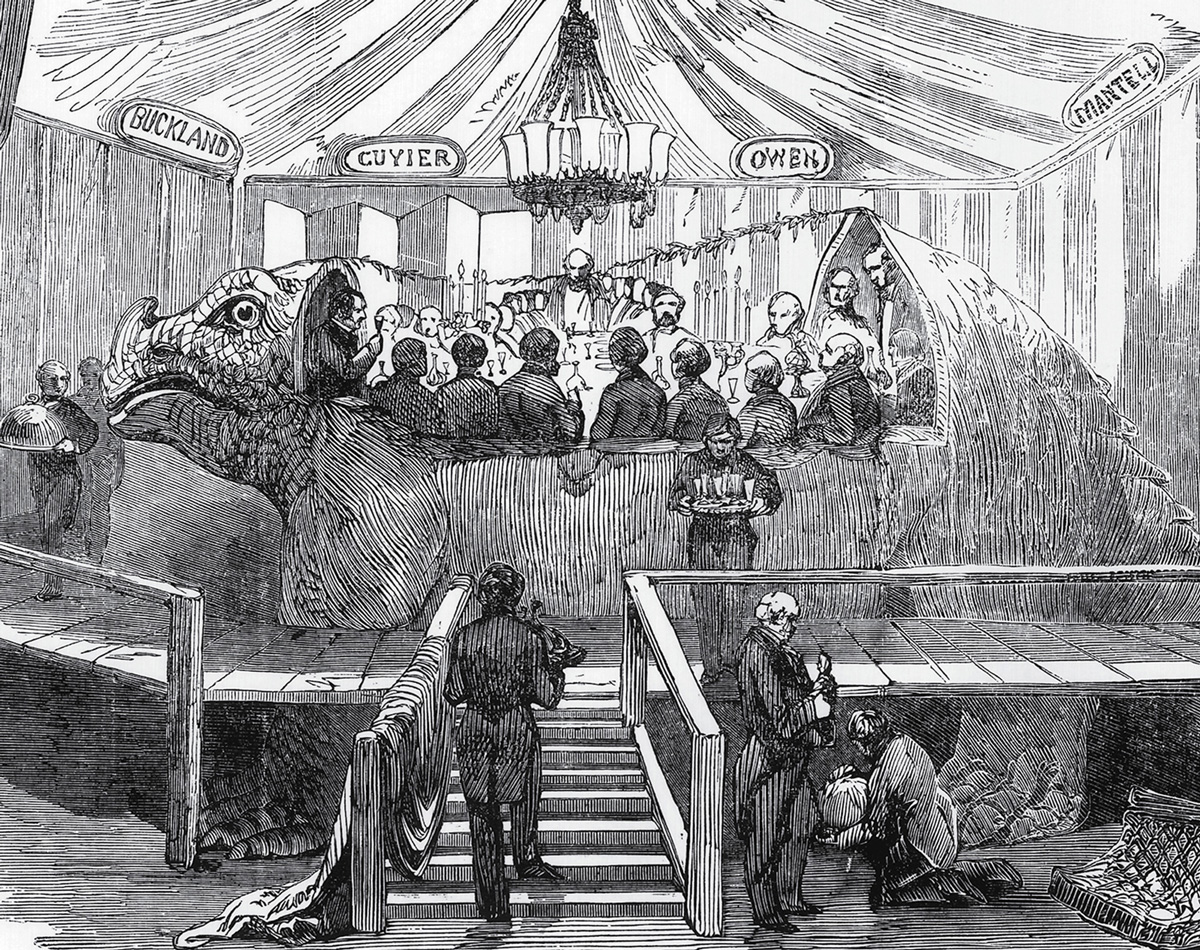

Hawkins imagined that visitors would encounter his sculptures by moving through a series of islands in the park which, when followed, would simulate a walk through millions of years of prehistoric time. A pair of Hawkins’s glorious Iguanodons, one standing erect while the other sits on its haunches, cozily resting one of its front paws on a little tree, still occupies a small island in the eastern quadrant of Crystal Palace Park. The standing Iguanodon had a fleeting moment of fame when Hawkins transformed it into the venue for a private dinner party for prominent naturalists of the day on New Year’s Eve in 1853. He positioned the mold for the standing Iguanodon sculpture beneath a striped tent, carefully removed the top layer to create an opening in its back, and inserted a dinner table complete with china, silver, and candles into the open space.

In 1868, while traveling on the lecture circuit in the United States, Hawkins was invited by a group of scientists in New York City to build new versions of his dinosaur sculptures for a museum of paleozoology that was being planned on the eastern edge of the newly-opened Central Park. Hawkins set up a workshop near the building site of the museum and began the laborious process of assembling the skeletal components of iron and brick. Work on the paleozoic museum caught the attention of William “Boss” Tweed, the notorious figurehead of the city’s corrupt Democratic political machine, who denounced the project (there was no apparent graft that could be had from an institution built around collecting fossils). Hawkins, a Londoner raised to believe in the virtue of making public declarations at Hyde Park Corner, held a demonstration in support of the museum during which he openly denounced Tweed. That evening, Tweed’s henchmen entered Hawkins’s studio and destroyed the dinosaur sculptures. Some believe that they buried the shattered fragments in Central Park. To this day, the skeletal remains of Hawkins’s American dinosaurs have never been recovered, their iron and brick bones undisturbed for more than a century and a half.

In 1878, a decade before Hawkins’s death, the first complete skeletons of Iguanodons were unearthed by two coal miners in Bernissart, Belgium. Examination of the full skeleton revealed that the spike Mantell, Owen, and Hawkins believed to be a horn was in fact a kind of thumb. Despite this paradigm shift, Hawkins never removed the spike or made any other anatomical corrections to his sculptures in Crystal Palace Park. Perhaps this was for the best. The dinosaurs remain as they were originally imagined, which at the time was cutting-edge science. But now, to us, the dinosaurs seem to represent a happy medium between the promise of comparative anatomy and the fantastic tales of dragon skeletons and enormous men. To this day, the spike sits proudly on the noses of all the Iguanodons that roam the parklands of Sydenham.

Brian Selznick has written and/or illustrated many books for children, including The Invention of Hugo Cabret (Scholastic Press, 2007) and The Dinosaurs of Waterhouse Hawkins (Scholastic Press, 2001), which was awarded a 2002 Caldecott Honor.

David Serlin is associate professor of communication and science studies at the University of California, San Diego, and an editor-at-large for Cabinet. He is the author of Replaceable You: Engineering the Body in Postwar America (University of Chicago Press, 2004).