Like a Hole in the Head

The trepanation-state

Christopher Turner

On a Sunday afternoon in December 1970, Amanda Feilding drilled a hole in her head. “There was quite a lot of blood,” she warns me when I visit her for lunch at Beckley Park—Feilding’s moated Tudor mansion just outside Oxford—and sit down to watch the short film she made of her DIY surgery. “It’s not a difficult operation,” she adds. Her pet African grey parrot nibbles her ear. “Drilling a hole in one’s head is really a nerve battle, doing something which obviously every instinct in your body is against. In a sense it’s quite satisfying that one can overcome one’s nerves to do it.”

The film, titled Heartbeat in the Brain, shows her shaving her hairline, putting on a floral shower cap to keep back her remaining locks, fashioning a mask out of sunglasses and medical tape, injecting herself with a local anesthetic, and peeling back a patch of skin with a scalpel. With a look of determined, almost trance-like concentration, Feilding then holds a dentist’s drill to her head and, pressing the foot pedal that operates it, begins to push its grinding teeth into the frontal bone.

Feilding was a twenty-seven-year-old art student at the time, and says that she was able to dissociate herself somewhat from the gory procedure by treating her head as if it were a piece of sculpture. She had arranged her tools in a neat row on a table draped in a white sheet. “I’m quite cautious and I’d prepared myself very carefully,” she explains, “I had an extra drill in case the other one broke down, which indeed it did. I’d gone into every detail.”

When she finally managed to bore through to the dura mater, Feilding grinned triumphantly as a geyser of blood gurgled from the half-centimeter-wide opening and poured down her face, spotting the white tunic she was wearing with carnation-sized stains. A reviewer who saw Feilding’s film in 1978, when she showed it at the Suydam Gallery in New York, reported that at the climax of the operation several members of the audience fainted, “dropping off their seats one by one like ripe plums.”

The film ends with footage of Feilding bandaging her head and mopping up the blood from her face with water and cotton wool. She changes out of her bloody tunic into a colorful Moroccan kaftan and wraps a shimmering gold turban around her head to disguise the bandages. Looking glamorous, bohemian, and elated, she smiles goodbye to the camera and heads off to a fancy-dress party.

• • •

Trepanation (from the Greek word trypanon, meaning “to bore”), the creation of a hole in the skull, is the oldest known surgical procedure. Perforated crania up to 8,000 years old have been found in prehistoric sites all over the world. Some of the holes, made by scraping away the bone with a flint or obsidian knife until a piece could be prised out, are the size of a man’s palm; other skulls have been pierced several times like a sieve. The majority of these apertures have soft edges, indicating that they had begun to heal and that there was a high postoperative survival rate.

Archaeologists have speculated that the operation was performed as a religious rite, an initiation into the priestly caste, or as a treatment for demonic possession—symptoms we might now diagnose as epilepsy, psychosis, or migraine. A hole in the head served as a mouthpiece to the gods, it was thought, or as a window that would allow bad spirits to escape.

Hippocrates and Galen gave detailed and careful instructions as to how to best perform the operation, which was used widely by doctors in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as a treatment for insanity, melancholia, and headaches, and remained common right up to World War One; a variety of gruesome-looking devices evolved as surgeons sought to perfect a drilling tool.

However, in the mid-1930s, when the Portugese neurologist Egas Moniz pioneered lobotomy—a procedure by which a deeper hole was drilled in the skull so that the prefrontal cortex of the brain could be mutilated using an instrument that resembled an apple corer—trepanation fell out of fashion and was relegated to the realm of superstition. The theory behind lobotomy was that you could destroy the parts of the brain that caused psychotic delusions, and for his work Moniz won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1949, by which time trepanation had become an almost extinct practice. In the course of the following decade, psychoactive drugs in turn began to supplant the even more brutal psychosurgery that had replaced it.

Feilding wasn’t interested in performing the operation as an extreme form of body art, but because she believed it would have a life-changing effect on her. She hoped that a hole in her head would increase what she terms “cranial compliance,” that alleviating the pressure in her skull would allow the heart to pump more blood to her brain, thereby giving her a new feeling of buoyancy. “If you don’t have that expansibility,” she says of the prison of inflexible bone that most of us have for skulls, “then the heartbeat pushes against the brain cells, which isn’t very good.”

Feilding tells me that she spent four years in the late 1960s trying to persuade a surgeon to trepan her. They all refused, reluctant to do such a procedure for its own sake without an indication. “If God had wanted us to have a hole in our heads,” they told her, “He would have given us one.” So she decided to do the operation herself: “Not that I’m in favor of self-trepanation,” she adds, “because I think it’s a ridiculous hoop for an untrained layperson to have to dive through, and quite dangerous, which is why I’ve only ever shown my film to small invited audiences. But at that point, it was the only way to see if trepanation actually makes a difference or not.”

Although Feilding entertains all manner of ambiguity in relation to her operation, she feels it did have a beneficial effect. “To my subjective experience I thought at the time that it was rather like the tide coming in,” she explains, “I felt a certain peace, it felt like a return, like I was rising in myself to a more natural level. But obviously one can say that that was a placebo, one can never tell with such a subtle feeling.”

Feilding first encountered the idea of trepanation at the age of twenty-three, when she met an eccentric and handsome Dutchman named Bart Huges, who was an advocate of the benefits of the procedure. She admits to having thought it “a bit freak” at first: “Bart quite changed my viewpoint,” Feilding says, “opening up doors of science and biology to me. He was very charismatic, we had a great love affair, and I was curious to see if what he said was true.”

• • •

Bart Huges trepanned himself in 1965. The operation took forty-five minutes, he later reported, but it took four hours to clean the blood off the walls and ceiling. Ten days later, at a public happening in Amsterdam’s Dam Square, he removed his bandages, which consisted of thirty-two meters of gauze that he’d painted with the words “HA HA HA HA” in psychedelic colors. When he visited a local hospital to obtain X-ray proof of his act, he was interrogated by psychiatrists, who suspected he was schizophrenic. He was held against his will whilst doctors performed three weeks’ worth of psychological tests. They were forced to release him when these tests indicated he was completely sane.

Huges, who had been a medical student but never graduated, was one of the first promoters in Europe of the consciousness-expanding qualities of LSD. He believed that when mankind evolved to walk upright, our brains drained of the blood with which they had previously been saturated. The limited blood supply was now concentrated in the parts of the cerebral cortex that developed language and reason, but there was, he argued, an overall dulling of consciousness. “Gravity,” he liked to quip, “brings you down.” He used to stand on his head in an attempt to defeat it.

Huges came to believe that trepanation, by creating an opening akin to a baby’s fontanelle, would allow the blood to freely pulse around the brain with every heartbeat, thereby creating a permanent high. In an eight-foot scroll articulating his ideas, Huges declared that those with holes in their skulls would be representatives of the new species Homo sapiens correctus.

Huges’s foremost disciple was a friend of Amanda Feilding named Joseph Mellen. Mellen, who had been educated at Eton and Oxford before he “tuned in and dropped out,” met Huges in the hedonistic party scene of 1960s Ibiza, where Huges introduced him to LSD. He went on to describe himself as “a sort of John the Baptist” and introduced Huges to Feilding in London in 1966. That summer Feilding helped Mellen drill a hole in his head, which served as a dress rehearsal of sorts for her own operation.

Huges had lent Mellen the money to buy an antique hand trepan, even though he had used an electric drill on himself, in the hope that Mellen would be able to prove that anyone, even those who lived in the Third World without access to electricity, would be able to enjoy the advantages of expanded consciousness. However, the centerpiece of the drill was so blunt that Mellen struggled for two hours to get it into the bone, a failure that was not perhaps helped by the fact that he’d steeled his nerves for the operation with LSD. He described his efforts in his unpublished memoir, Bore Hole, as “like trying to uncork a bottle from the inside.” The book reads something like an unintentional comedy of errors.

Mellen phoned Huges, who was in Amsterdam with Feilding, and he agreed to return to England to help. However, Huges was refused entry into the country (an interview he’d done before he left London had resulted in the unhelpful headline, “This Dangerous Idiot Should be Thrown Out”), and Feilding aided Mellen in his place, using all her might to get the point of the trepan to hold so that the teeth of the drill could find a grip. Mellen, again high on acid, took over the drilling until he blacked out. Feilding phoned for an ambulance and he was rushed to hospital.

Feilding and Mellen began seeing each other after she separated from Huges—they would go on to marry and have two children together. Yet Huges’s influence continued to dominate their lives. The following year, after Mellen had spent a week in jail for possession of cannabis, Feilding assisted him with another attempted self-trepanation. “I found the groove from the previous operation and got going,” Mellen wrote in his memoir: “After some time there was an ominous-sounding shlurp and the sound of bubbling … It sounded like air bubbles running under the skull as they were pressed out.” However, when he examined the trepan it held an irregular sliver of bone, and when he didn’t feel the expected difference in mood, he attributed this to his having drilled through at an angle. The hole he had managed was evidently too small.

Three years later, Mellen armed himself with an electric drill and tried again. Once more, things did not go smoothly. This time the drill burned out and he had to bandage his head mid-operation and go downstairs to ask a handy neighbor to help him fix it. The repair took an hour.

The next day Mellen resumed the operation, and finally achieved success:

Steadily, almost imperceptibly, over the next four hours I felt myself get higher and higher. I got higher than I had thought possible. I felt so light and free. It is very hard to put in words the feeling of change, but I felt very relaxed, as if everything would fall into place now.

• • •

When Feilding returned from New York a few days after Mellen’s successful trepanation, she was persuaded that he had undergone a change for the better. “The difference is very subtle,” she explains. “Basically, I put it that the neurotic side of the person has a little less grip—because they’re higher, they have a little more bounce. The floor has been raised a bit, the balloon has been blown up a little bit more. It doesn’t mean it cures the neurotic bag, but I do think it lessens it slightly.” Several months later, she made up her mind to trepan herself, with Mellen on hand to film it. Learning from his mistakes, she performed what she describes as “a faultless trepanation with a very neat scar.”

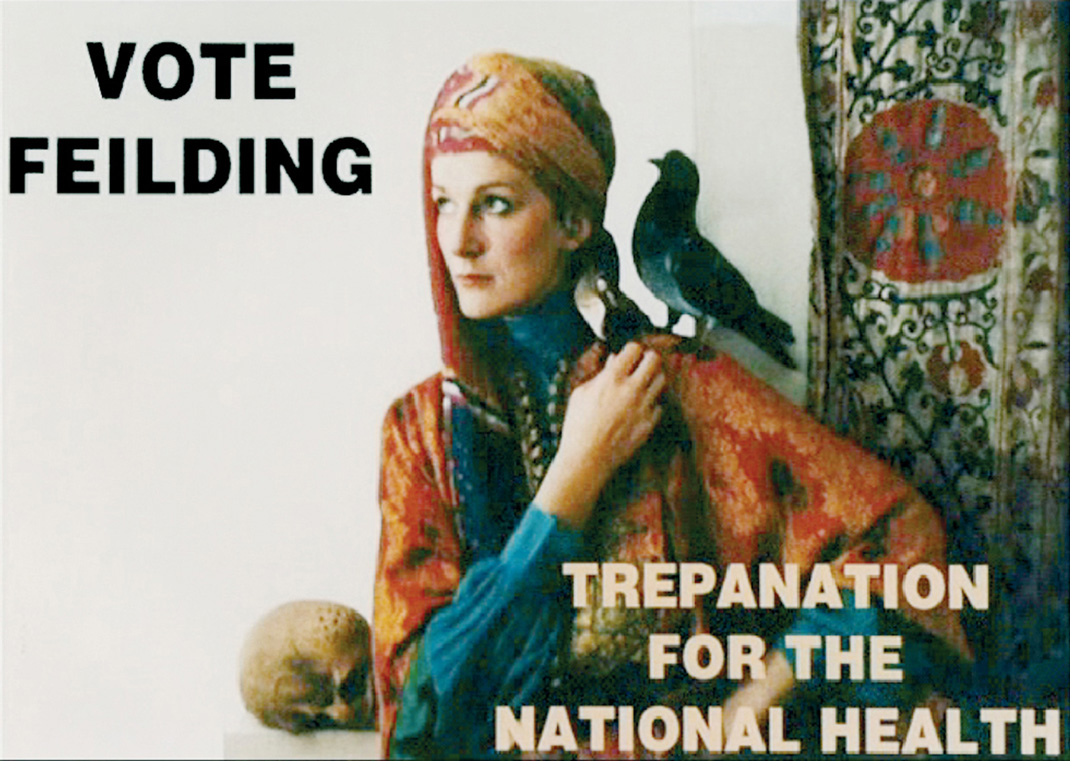

Feilding became a leading propagandist for the benefits of trepanation. She stood for Parliament as an independent candidate in her local constituency of Chelsea in 1979 and 1983, campaigning on the sole platform that trepanation should be freely available on the National Health Service, doubling her share of the vote from 49 to 139 in the process (one journalist at the time asked whether these were gestures of support or protest, a way of saying that the country needed Mrs. Thatcher about as much as it needed a hole in the head).

Feilding and Mellen separated after twenty-eight years together; both of them persuaded their subsequent partners to be trepanned. In 1995, Feilding married Lord Neidpath, a former professor at Oxford who taught international relations to Bill Clinton. He found that the terrible headaches he’d suffered from all his life ceased after trepanation.

Feilding is still a supporter of the procedure, and has started up the Beckley Foundation to commission research into the possible benefits of trepanation (the Foundation has also obtained permission to conduct the first study in thirty years of the effects of LSD on human subjects; it will test the neural changes brought about by the drug). She has funded the investigations of a scientist in St. Petersburg, Yuri Moskalenko, who is a pioneer in the field of cerebral circulation and has performed a battery of neurological tests on patients who have had their skulls opened in order to have cancerous brain tumors removed.

Feilding believes his findings “provide incontrovertible evidence” that trepanation does bring about real neurophysiological changes. Whether those changes are beneficial or not remains an open question. Even within the tight knit circle of Huges’s disciples, not everyone has been so convinced: Huges’s own sister reported that trepanation had no effect on her at all.

Feilding estimates that there are perhaps several dozen people alive today who have been trepanned. I ask her whether she envisages a utopia in which, one day, we all have holes in our heads and access to a higher plane. “On the whole, people remain just as disappointing untrepanned or trepanned,” Feilding laughs. “Just because someone is trepanned it doesn’t mean that you like them any more.”

In 2000, Feilding traveled to Mexico City to have a second hole drilled in her head because she felt the one she’d made in 1970 with a dentist’s drill had closed up. The surgeon, who she found after many closer to home refused, once again, to help her, performed the operation with a hand-cranked trepan. “I would choose my self-trepanation any day,” Feilding says of his clumsy job, “but I felt incredibly well after having it, pleased to be me. But obviously a subjective difference is not enough to convince anyone.”

“If it is a placebo effect, I’d love to know,” she says, open to doubt. “Then one can just draw a line under that subject and see it as a kind of cultural artwork. I still have a burning ambition to discover what the truth is. But from my own experience I think there is a change, otherwise I wouldn’t be bothering about it forty years later.”

Christopher Turner is an editor of Cabinet. His book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came To America, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.