Fatigued

Philosophies of fatigue

Marina van Zuylen

In the frenetic lives we lead, while it is not unusual for us to brag about our late nights at work, to recount feats of heroic exhaustion at the gym, we would rather be caught dead than admit to a most excellent bout of napping or a particularly enjoyable daydream. We use our precious days off catching up on email and have even been spotted at the movies taking notes for an article that we may never write. There seems to be no time to waste anymore and our Sisyphean tasks and travails fill us with a reassuring sense of exhaustion. Exhaustion, indeed, has a curious way of eradicating more complex signs of weariness, one of which being the indeterminate state we call fatigue. Being exhausted signifies having paid one’s dues to society. Fatigue, on the other hand, generally connotes a weakened state, a deviation from the affirming inevitability of cause and effect, work and repose.

Like boredom and depression, fatigue is a porous state that lies at the margins of consciousness. From the murky nineteenth-century concepts of asthenia and neurasthenia, to recent discussions of chronic fatigue syndrome, fatigue has in turn been lambasted as proof of cultural decadence, analyzed as an offshoot of alienated modernity, or praised as the sign of our willingness to engage in the impossibly taxing business of ethical living. Historically, fatigue has been looked down on as a malady of the will, the offshoot of excessive introspection, and a blood relative of laziness. Uncomfortable, indefinable, it is an unsettled and unsettling topic that no great philosopher tackled before Emmanuel Lévinas, who did so in his 1947 book Existence and Existants. So why the recent interest? Slowly catching up with laziness, fatigue is emerging as a force to be reckoned with. Anson Rabinbach’s The Human Motor, Jean-Louis Chrétien’s De la fatigue (On Fatigue), and last but not least Alain Ehrenberg’s La Fatigue d’être soi (The Fatigue of Being Oneself) have all made it clear that post-Enlightenment culture entertains a curious love-hate relationship with fatigue. Its eradication would usher in an age of absolute energy and accomplishments, while its cultivation could lead to radical self-knowledge. Fatigue, then, is both “a natural barrier to the efficient use of the human motor,”[1] and, for the likes of Baudelaire and Schopenhauer, the most promising way to unlock the central mechanisms of our being.

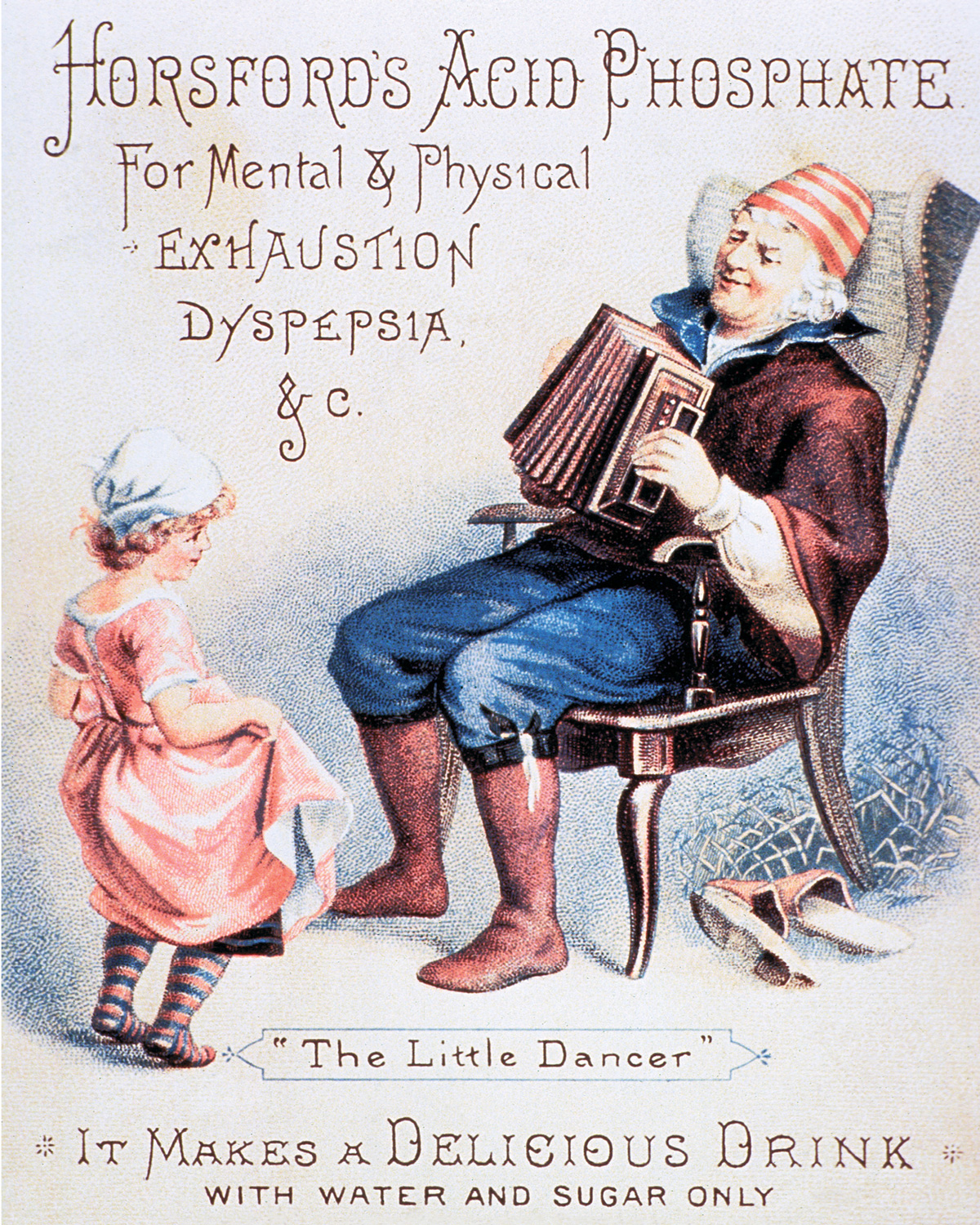

Feverishly discussed in the nineteenth century and heavily diagnosed in over-populated cities like Paris and London, fatigue was blamed on a host of interlocking causes—the new expectations democratic society placed on its citizens, expanded leisure time, and the monotony of mechanized work. Manuals such as Marc-Antoine Jullien’s 1808 Essai sur l’emploi du temps; ou méthode qui a pour objet de bien régler l’emploi du temps (Essay on Scheduling, or a Method for Living a Well-Regulated Life)[2] offered “idle characters” a host of practical solutions designed to combat bodily and intellectual fatigue. Jullien believed that by measuring and cutting up time in rhythmical and orderly sequences, one could get rid of the dangerous idleness that resulted in mind-numbing weariness.[3] He makes clear that as civilization advances and as we rely less and less on the body to perform daily tasks, fatigue travels from our bodies to our souls. Cold showers, large quantities of tea and coffee, programmed meals, promenades, praying sessions, and esoteric games were offered as antidotes to the disruptive and antisocial manifestations of fatigue. But these measures were obviously too mild, and one had to wait for the drastic solutions of utopians-turned-scientists to dream away fatigue altogether.

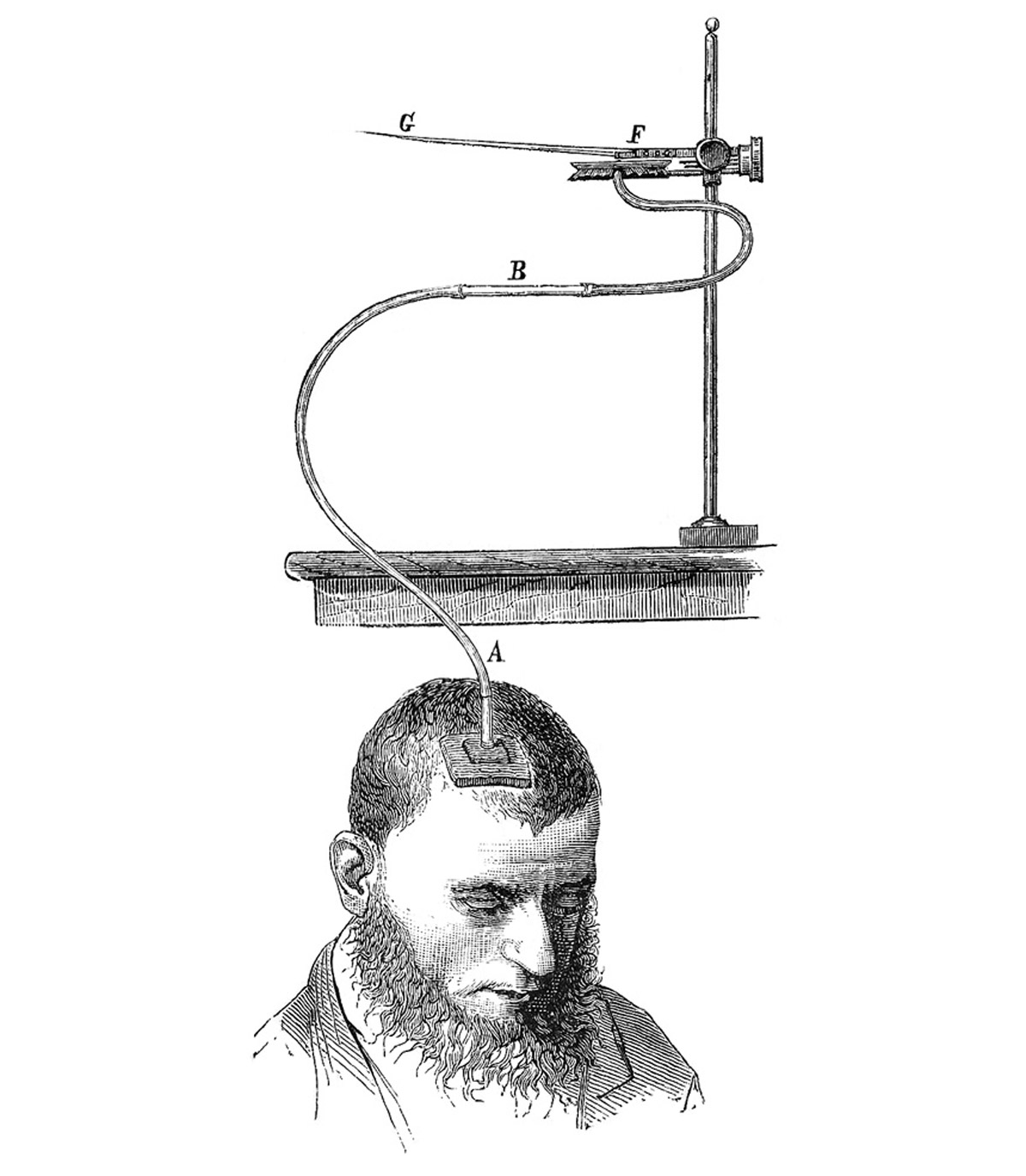

Whether in the hopes of boosting productivity, reducing workers’ fatigue, or combating self-indulgence, fatigue-eradication was at its apogee in the early twentieth century. In 1904, for example, Wilhelm Weichardt’s monomaniacal desire to exterminate fatigue caused him to invent a sprayable vaccine for German classrooms to help combat harmful fatigue toxins that built up in students’ bloodstreams. A few years earlier, Angelo Mosso’s bestselling La Fatica (Fatigue; 1891) had convinced readers that fatigue could not only be objectively described, but analyzed and controlled. His desire to help workers by easing their fatigue led him to experiment with muscular mechanics, inspiring him to invent the ergograph—a work recorder—in order to understand the principles of endurance and energy. In an attempt to find a cure for fatigue, experiments were conducted with all sorts of stimulants, narcotics, and dietary regulations to determine the relationship between mental and physical exhaustion. Mosso’s dark assessment of the fatigued citizen—drooping, yawning, spasming—belongs to the extensive literature written by the veritable army of fatigue-fighters and laziness-debunkers that riddled the French, Italian, and even the American psychiatric landscape between the 1880s and World War II.[4] These physicians were out to prove that fatigue was just another physiological, and therefore solvable, obstacle to the development of the New Man.

Leading parallel lives, good fatigue and bad fatigue were intricately connected. While Proust was meditating on the phenomenology of sleep and wakefulness, his father Adrien was busy promoting cures against exhaustion.[5] And while Flaubert was documenting Emma Bovary’s unthinking surrender to fatigue, he was summoning his readers to a self-conscious version of this weariness through the painstaking act of reading. In contradistinction to escapism (the great antidote to existential fatigue), Flaubert, ushering in Modernism’s principled difficulty, was transmitting his characters’ plodding life-rhythms to his audience, trying to infect the reader with a pedagogically enriching fatigue. “My secret aim,” Flaubert writes about his unfinished Bouvard et Pécuchet, “is to make the reader so catatonic that he will go mad. But my goal will never be achieved … the reader having immediately fallen asleep.”[6] Flaubert might have initially failed to convert his painstaking writing style into real-life weariness, but the trend had been set. What famously fatigued characters such as Goncharov’s Oblomov or Melville’s Bartleby had achieved on the thematic level, artists from Chekhov to Beckett would radicalize performatively. By dismantling the Aristotelian dependency on catharsis and robbing their protagonists of the impulse to act, they were placing inertia at the center of theatrical production and causing the public to be seized with bouts of unendurable fatigue. At the end of an action-packed century, an era that promoted progress over introspection, plotting over plodding, the arts were pinning great hope on ontological fatigue. It was as though cultivating it would counteract positivistic thinking and reinstall slowness and self-doubt as a new aesthetic motor.

In the political register, a book like Alain Ehrenberg’s La Fatigue d’être soi (2000), connects lassitude not with productive introspection but with society’s craving for lost authority.[7] Ehrenberg argues that depression stems from “the fatigue of being oneself,” from the exhaustion caused by democracy’s abnegation of authority. How could one not be overcome by melancholy, the author argues, when every life decision is up to us? Neither church, nor family, nor government tells us who to be; our identity is all ours to determine and to perform. Vaguely echoing Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor, Ehrenberg warns us that free will is more grueling than meets the eye, and that most of us are not up to it. If so many teenagers are curled up somewhere in a state of larval inaction, it is because they have too many choices and not enough guidance. The book is both persuasive and condescendingly dangerous. It taps into our own overachieving fear of free time and tries to convince us that had we fewer choices, we would avoid those disorienting moments of idleness, those very moments where boredom and fatigue coalesce and where pill-popping is at its apogee. We demand from our favorite chemicals—against depression, attention deficit disorder, oversleeping, or sleeplessness—that they mitigate those in-between moments.

While Ehrenberg warns that our addiction to palliatives is the natural result of democratic chaos, he is tapping into a conservative version of what Georg Simmel saw as the sensory overflow bred by the urban experience.[8] The ease with which pleasure could and can be achieved (from brothels to arcades, from iPods to instant messaging) causes our senses to become stunted, demanding an ever-greater intensity of excitement. Stopping such a desiring process is almost impossible. For both the nineteenth-century flâneur and the present-day jaded web-surfer, fatigue attaches itself, Ehrenberg claims, to an insular and narcissistic body that has lost its ties to a greater purpose. It would be unfair to accuse Ehrenberg of encouraging a return of authority. Still, his warnings hark back to the perennial fear that unless the hours of the day are properly accounted for, free fall into bored and self-destructive introspection will ensue. Sectioning the day into a regimen of puritanical tasks and overscheduling ourselves into “healthy” exhaustion appear to be the only viable alternative, making “good” tiredness the sole route to a successful life.

If we recall the rhetoric of Fascism, Mussolini also believed in structured leisure and fatigue management: he forced the unruly masses to spend their Saturday nights at the opera by giving them free tickets, legislating Verdi over vino. This was supposed to keep his citizens busy, rested, and diverted at the same time. Lack of choice, it was understood, would turn the body into a well-oiled machine that would miraculously be saved from the lethal “in-between,” from melancholy-generating free time.

A new history of philosophy around such indeterminate intervals is overdue. From Pascal to Baudelaire, from Proust to Lévinas, the French tradition has been particularly sensitive to these uncomfortable threshold-moments, making them a central ingredient in their definition of the human. Lévinas makes fatigue, and particularly “dead-time,” one of the cornerstones of the thinking process, pairing it with the benefits of insomnia, and pressing us to consider it as our chance to be optimally alert to our condition.[9] Against all logic, he invests fatigue with a moral dimension, seeing it as a heightened state of consciousness, a wakeful mission that will rekindle and seal our contract with ethics. While weariness spells out our refusal to exist, and while indolence postpones any sustained mode of engagement, fatigue gives us a chance to take stock of our “hesitation to live.” To Lévinas, it is incumbent on the philosopher “to put him or herself in the instant of fatigue and discover the way it comes about. … And to scrutinize the instant, to look for the dialectic which takes place in a hitherto unsuspected dimension.”[10] Pushing this idea of strain even further, Lévinas holds insomnia as the most promising step toward self-knowledge. As forbidding as a plotless novel or an atonal piece of music, insomnia takes fatigue to its foremost point of discomfort. Prisoner of an inextricable dialogue with a selfhood that cannot settle down, the insomniac falls into a Beckettian pattern of waiting. The degree of anxiety born from this quasi-state of paralysis, a locked-in syndrome of sorts, makes thinking the only option. Insomnia, then, is “an indefectibility of being, where the work of being never lets up.”[11]

In terms of the cultural history of fatigue, Lévinas’s scrutiny of idle attentiveness turns on its head the more conventional nineteenth-century dichotomy between fatigue-ennui, on the one hand, and virtuous volition, on the other.[12] Théodule Ribot developed this distinction in his 1883 Les Maladies de la volonté (The Diseases of the Will), his concept of boredom closely resembling Lévinas’s state of insomnia, but without the positive spin.[13] To Ribot, volition is something reassuringly final; it is what allows us to “close the deal” by converting any dangerous self-scrutiny into a decisive step. Nothing is further from Lévinas than such a wish for closure, the latter belying the end rather than the beginning of thought. The ethical contract that Lévinas locates in fatigue coincides instead with an awakening, not the smug solidification of calculated decisiveness.

One of Lévinas’s great forerunners in the rehabilitation of fatigue was Baudelaire, whose vicious attack against hashish in Les Paradis artificiels (Artificial Paradises) was rooted in his critique of a sensation-seeking ethos that would lead to a debilitating emptying-out of selfhood. For Baudelaire, whatever is not produced by effort and hard thought, whatever chemically obliterates doubt and anxiety, is dismissed as “fortuitous and slavish energy.” Because it creates false enthusiasm and “smug laziness,” it ends up producing exactly what it was eschewing—an “immense fatigue.” Clearly, Baudelaire wants to distinguish between the good and the bad brands of fatigue that his century was clumping together without discrimination. Far from being a shameful pariah, good fatigue actually regulated our core being. He recognized in it that very element from which his hashish-consuming friends in the Club des Hashischins (Jacques-Joseph Moreau de Tours, Théophile Gautier, Gérard de Nerval) were desperate to escape—namely, the discomfort and anxiety born from a state-in-waiting, the state that occurs before resolution, whether it be pleasure or pain. Baudelaire clamors for the return of such a threshold-state, as crucial to life as is a pause in a conversation.

But Baudelaire’s hashish-eaters, like the fatigued citizens described by Ehrenberg, are absolutely resistant to downtime, to the only time where fatigue can actually be reckoned with. “The result of opium for our senses is … to adorn the whole of nature with a supernatural interest, one that endows each object with a more profound, more willful, and more despotic meaning.”[14] Hashish disguises the mute and still quality of objects, making them aggressively interesting and unnaturally interactive. It also artificially heightens our consciousness, robbing it of the chance of framing the world on its own terms. Boosting reality by resorting to chemicals dissipates “concentrated selfhood,” provoking the quick fix that will contribute to the “loss and evaporation of the soul.” The drug, rather than distilling perception, will dilute it, provoking “the same decay that surfaces in all modern inventions that tend to diminish human freedom and imperative suffering.”[15] Baudelaire’s meditation refuses all of modernity’s escape routes, forging instead a fraternal bond with idleness and fatigue, two of its fundamental tenets. Drugs or disciplining manuals, while taking the edge off of self-doubt, wipe out that beneficial fatigue of being oneself, however cursed such a condition happens to be. Baudelaire’s Paradis artificiels attempts to restore a curiously stretched fatigue, one that hovers between lucidity and despair, on the verge of becoming a philosophical entity in its own right.

Like hunger, fatigue always comes back to haunt us. Conventionally symbolizing introspection’s defeat, to more adventurous minds a life without such fatigue will ultimately produce nothing but monotony and disgust. Fatigue, after all, structures stillness, adds texture by resisting a temporality that usually imposes itself from without. But to protect our internal sense of time by cultivating our fatigue is no easy task. So once again, we are confronted with a seemingly impossible choice: do we become attentive to our excruciating fatigue, do we court our insomnia, or do we chase it away, only to replace its vague symptoms with the legitimizing pain of physical or mental exhaustion? For a start, we might recognize the masochism in both of these gestures: each alternative involves pain.

Whatever, then, happened to the blissful fatigue that belongs neither to the worked-out body nor to the introspective soul? Where is the liberating fatigue that catches us off-guard, fending off the mindless stimuli of the everyday? As gratuitously perfect as the smoking of a cigarette, it is the delicate threshold separating sleep and non-sleep; it is that second or minute stolen from time and space—our private access to the sublime. Too fleeting to be over-examined, it has nothing to do with Baudelaire’s fatigue-as-death-wish or with Lévinas’s ponderous reflexivity. Its unpredictable jumps and starts, the sudden thoughts it unleashes and steals back, restore us to ourselves as we slip in and out of the accidental and inexplicable joys of momentary unconsciousness.

- Anson Rabinbach, The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity (Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1990), p. 133.

- Marc-Antoine Jullien, Essai sur l’emploi du temps; ou méthode qui a pour objet de bien régler l’emploi du temps (Paris: Didot, 1808).

- See Alain Corbin, L’Avènement des loisirs 1850–1960 (Paris: Flammarion, 1995), pp. 129–130.

- Anson Rabinbach describes at great length Mosso and his fatigue-measuring ergograph, Ferré and his connecting fatigue and crime, and Ferrero’s campaign against indolence—figures all convinced that fatigue was one of the sure signs of modernity’s decadence.

- Rabinbach, The Human Motor, pp. 156–160.

- Quoted by Philippe Sollers, “La Rage de Flaubert,” Le Nouvel Observateur, 20 December 2007, p. 108.

- Alain Ehrenberg, La Fatigue d’être soi. Dépression et société (Paris: Odile Jacob, 2000).

- See Kevin Aho, “Simmel on Acceleration, Boredom, and Extreme Aesthesia,” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, no. 37 (2007), pp. 447–462.

- For a superb discussion of dead time, see Elissa Marder’s Dead Time: Temporal Disorders in the Wake of Modernity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001).

- Emmanuel Lévinas, Existence and Existents, translated by Alphonso Lingis (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 2001), p. 18.

- Lévinas, Existence and Existents, op. cit., p. 62.

- For a comprehensive discussion of boredom, see Elizabeth Goodstein’s Experience without Qualities: Boredom and Modernity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005).

- Théodule Ribot, Les Maladies de la volonté (Paris: Germer Baillière, 1883).

- Charles Baudelaire, “Eugène Delacroix,” Exposition Universelle 1855, in Oeuvres completes II (Paris: Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1975), p. 595.

- Baudelaire, Paradis artificiels (Paris: Gallimard/Folio, 1964), p. 69.

Marina van Zuylen is professor of French and comparative literature at Bard College. She is the author of Difficulty as an Aesthetic Principle (Tübingen, 1993) and Monomania: The Flight from Everyday Life in Literature and Art (Cornell University Press, 2005). She is presently writing a book about idleness.