Four Leaves from a Commonplace Book

Cut and paste

D. Graham Burnett

Reading is perhaps best understood as a peculiar form of writing, and vice versa. Renaissance thinkers took this paradox very seriously, giving it concrete form in their “commonplace books,” manuscript journals of passages copied from assorted texts and organized under various headings. The origins of the practice lay in the preparatory methods of classical oratory and medieval sermon composition, but commonplacing achieved the status of a true art among humanists like Erasmus and Montaigne, who used these notebooks to maintain command over an ever-expanding body of published texts, while culling material for their own correspondence and literary compositions. Never merely a means to those ends, the well-wrought commonplace book—an elaborately configured bibliographical collage, capable of making new meanings out of juxtaposition and excision—eventually became a way of thinking about thinking itself. What started as an aide-mémoire began to look like a theory of mind.

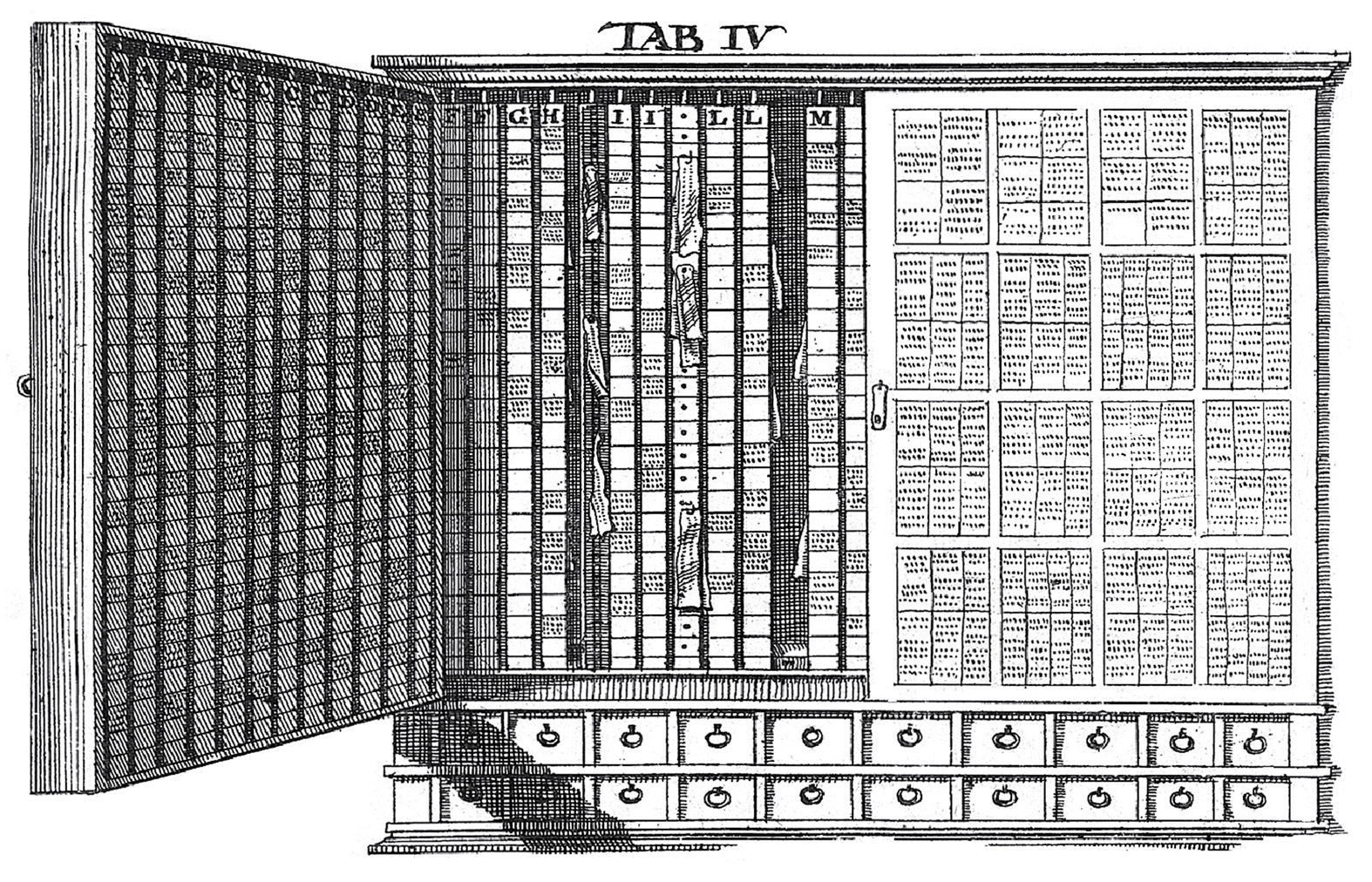

For the apotheosis of this tradition, consider the illustration here, which shows an arca studiorum or scrinium literatum, a “literary chest”of commonplaces, penned on cards and impaled on subject-heading hooks (this one hails from Vincent Placcius’s De arte excerpendi vom gelahrten Buchhalten liber singularis of 1689). These devices—mobile, expandable, easily rearranged, and cross-referenced—were the cognitive prosthetics of the early modern period.

Following are excerpts from a project by D. Graham Burnett, who has worked for several years on a set of departures from the tradition of the commonplace book.

—Anacharsis, a worker,

Callused Tradition, or The Repair of Self-Made Men, 1849

—Fabrizio Delmano,

A Tour of the Apricot Stone, 1873

—Arthur Smith,

Hounds and Heaven: Metaphysics in the Kennel, 1905

—Refugio Soltero-Cane,

Iron Bellows, Paper Forge, 1922

—Max Dash,

On Foot in Ischia, 1902

—Lucius Surd,

“‘To peck herself a precious stone’: Robert Frost at Amesburg,” Lot’s Wife, A Quarterly, 1969

—Xavier Klasi,

Heidegger and the Accidents, 1976

—Peter Legg et al.,

“Disruptive hatching behaviors and retinal asymmetries in domestic chicks (Gallus gallus),” Developmental Psychobiology, 1987

—Nat VonGriff,

Falsification among Organized Birdwatchers, 1959

—Cullen Stroke,

Shorthand for All Seasons, 1923

—Isabel and Henry H. Robert,

A Parliamentary Practicum, 1902

—Dr. Labalee Black,

Mutatis Mutandis: Cures for the Glossopetric, 1896

‘Kings should disdain to die, and only disappear.’”

—Thomas De Quincey,

Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, 1821

‘and there remaineth a Paste in divers Balles, called the Almond Paste, which by a limbecke receiving fire, causeth the Quickesilver to Subleme, and falling downe the neck into the water, which is in the receiver stopped close, taketh his bodie again.’”

—Michael Faraday,

Three Lectures on the Chemical History of a Candle, 1859

‘But Princes (like the wondrous Enoch) should be free

From Death’s Unbounded Tyranny,

And when their Godlike Race is run,

And nothing glorious left undone,

Never submit to fate, but only disappear.’”

—Vatticus Wesley,

The Mirror of Satan, 1879

D. Graham Burnett is a historian of science at Princeton University, and the author of four books, most recently Trying Leviathan: The Nineteenth-Century New York Court Case that put the Whale on Trial and Challenged the Order of Nature (Princeton University Press, 2007), which won the 2008 New York City Book Award. This fall, he and Jeff Dolven will be teaching a graduate seminar on the practice of criticism in the arts titled “Critique and Its Discontents” for Princeton University’s Council of the Humanities.