The Moviegoer as Spelunker

Robert Smithson’s underground cinema

Colby Chamberlain

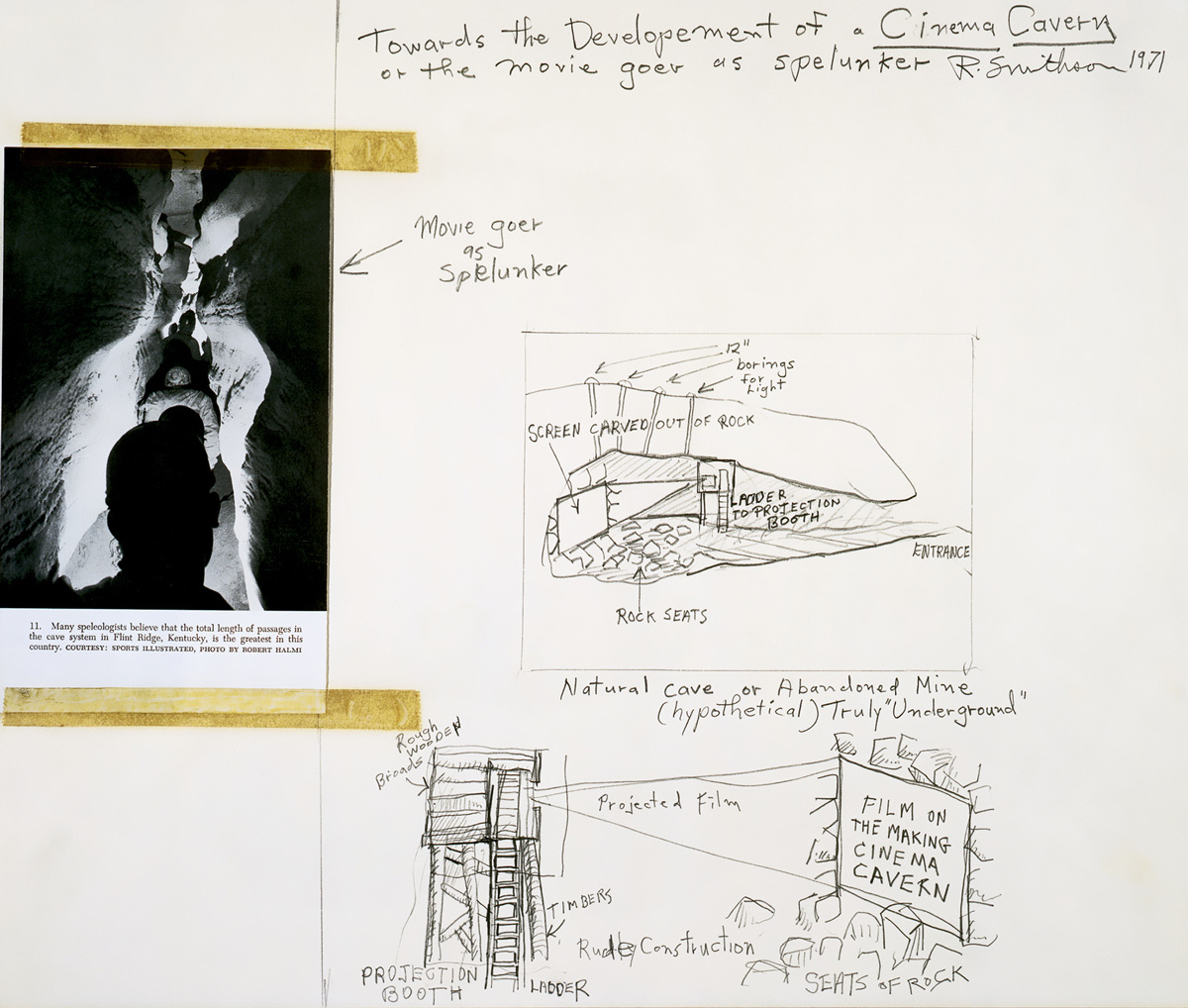

Godard may be right that a movie needs only a girl and a gun, but a movie theater’s requirements are significantly more complicated: sound-proofed projection booth, aluminized screen, rows of strategically staggered chairs, syrupy concessions, adjacent restrooms, and, of course, a dark, cavernous space. It’s a daunting checklist, but in a 1971 sketch the artist Robert Smithson proposed that a converted cave or abandoned mine might pass muster. His drawings are hasty (and his spelling dubious), but, popcorn aside, the necessary trappings are all there: “The projection booth would be made out of crude timbers, the screen carved out of a rock wall and painted white, the seats could be boulders,” he wrote in an essay of the same year. “It would be a truly ‘underground’ cinema.”

Cordoning off “underground” in scare quotes, Smithson winked at the break between his own geologic frame of reference and the word’s entrenched cultural connotations. In the years preceding Smithson’s sketch, “underground” had gone from an occasional shorthand for peripheral political and aesthetic movements to a proper (if penniless) market niche. In 1967, counterculture presses from New York to as far away as Australia organized officially as the Underground Press Syndicate to share and distribute their content globally. For cinema, Stan VanDerBeek was first to apply “underground” to a generation of experimental filmmakers—Ken Jacobs, Robert Breer, Stan Brakhage, and others—knit into the collective business ventures of Jonas Mekas, whose Film-Makers’ Coop and Film-Makers’ Cinematheque became the principal commercial structures for distributing and screening their work. Aided and abetted by Andy Warhol’s 1963 move into film and by the ballyhooed pseudo-obscenity of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures, the underground marquee attracted a mixed bag of popular attention and prurient curiosity. Time, Newsweek, and other decidedly surface-dwelling presses duly dispatched journalist-spelunkers to cover the dangerous-seeming, ludicrous-sounding goings-on of Lower Manhattan’s makeshift theaters. In 1965, a Life columnist reported:

The other night I infiltrated a crowd of 350 cultivated New York sophisticates who were squeezed into a dark cellar staring at a wrinkled bedsheet. The occasion was the world premiere of Harlot, yet another of the rash of “underground movies” which have become the current passion of New York’s avant garde. Word of the esthetic uproar the underground movie craze has stirred up for the past year had finally reached us out in Hollywood, and I had come east to see if my hometown film industry has anything to worry about. I think we do: if a bunch of intelligent people will spend two solid hours and $2.50 apiece to see a single, grainy, wobbly shot of a man dressed up as Jean Harlow eating a banana (that’s what we saw in the cellar), then the movie business must be in worse shape than anyone has any idea.

But however much the term has concreted around his community of filmmakers, VanDerBeek was not, in fact, the first to advance the notion of an underground film. That particular distinction goes to the painter and critic Manny Farber, who coined the term in 1957 in praise of Howard Hawks, Val Lewton, and other directors of 1930s and ‘40s action flicks. To Farber, these filmmakers were unsung masters, working shrewdly and nimbly within shoestring budgets and strict genre conventions. (Farber’s reconfigured filmmakers’ pantheon corresponds closely to that of Cahiers du Cinema, then the organ of the French New Wave). His rationale for labeling these directors “underground” was twofold: First, their works were primarily screened in decrepit “outcast theaters.” Second, and more significantly, these directors exercised their intelligence below the narrative arc, “far within,” as Farber put it, “the earthworks of the story.”

Smithson seems to have shared Farber’s indifference to the surface elements of a film. “All those ‘characters’ carrying out dumb tasks,” he complained. “Actors doing exciting things. It’s enough to put one into a permanent coma.” This semi-comatose spectator suggests a peculiar inspiration to the Cinema Cavern: At the edge of his sketch is a magazine clipping of a figure proceeding down a narrow tunnel; the “movie goer as spelunker” Smithson labels him. Imagine that the Cinema Cavern is just to the left. The spelunker enters, and settles onto a boulder. A single film, Smithson’s “The Making of Cinema Cavern,” plays on a continuous loop. “Among the flickering shadows,” predicts Smithson, “his perception would take on a kind of sluggishness.” With time, the frames muddy into abstractions, and the spelunker “would not be watching films, but rather experiencing blurs of many shades.” Still he gazes from the rocks, captivated by the shapes flickering across the stone: Smithson’s theater collapses into Plato’s Cave. … Or perhaps our spelunker steers right, and errantly barges into the speakeasy theater that French police recently discovered beneath the sixteenth arrondissement of Paris. According to a 2004 Guardian article, the well-accoutered illicit establishment included carved balconies, working phones, a generously stocked bar, and a cache of truly “underground” cinema: 1950s film noir.

Colby Chamberlain is managing editor of Cabinet.