Down the Tube

Frank Pick’s underground dream

Michael Saler

There is an underground; there are undergrounds; there is the Underground. The first might be defined as a metaphorical space in which individuals plumb the depths of their souls, the site of Dante’s Inferno and Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground. The plural term “undergrounds” connotes counter-cultural movements, including the social (“underground railroad”), the political (“French resistance”), and the aesthetic (your favorite goes here). The capitalized “Underground” is ostensibly more prosaic than either of these, a transport system in London that will get you from A to Zed. The three terms are clearly distinct, yet in the 1920s and 1930s they were unexpectedly aligned: the London Underground became the home for the aesthetic underground, largely as a consequence of the interior odyssey of its executive officer, Frank Pick.

Though best known for making the Underground into an important patron of modern art in interwar England, Pick was not merely a savvy businessman who turned avant-garde art to commercial advantage. He and many of those he worked with were beholden to the nineteenth-century Arts and Crafts movement. Like John Ruskin, William Morris, and others in this tradition, they wanted to efface the arbitrary distinction between so-called “fine art” and “craft,” and to integrate art with life as it allegedly had been in the pre-modern period. The Underground system was to be the culminating project of the Arts and Crafts movement, recasting Ruskin and Morris’s nostalgic, anti-industrial vision into one compatible with modernity.

As unlikely as this aspiration appeared, Pick’s ultimate aims were even more grandiose. For him, modern art encapsulated the “living spirit” that would “re-energize religion.”[1] Its abstract designs and rhythmic forms would instigate spiritual cohesion in a secular age. He intended the Underground to be the template for an aesthetically and organically unified London. As an administrator he would also be an artist, using the physical layout of the system to transform the sprawling metropolis from an impressionist work—undefined, stippled with isolated individuals pursuing their own ends—into a clearly bounded post-impressionist work, its citizens united by common purposes. Commuters who descended into the Underground during the interwar period often marveled at the modernist styles they encountered, but they would have been even more astonished to learn they were en route to the Earthly Paradise.

The London Underground thus became conjoined with the aesthetic underground during the interwar period, largely as a consequence of Pick’s inner spiritual voyages. It is an improbable story, but ultimately an instructive and hopeful one. When one considers the odd convergence of practical and aesthetic transports, subway stations and utopian destinations, one wonders about other historical possibilities that remain submerged, awaiting resurrection. Walter Benjamin argued that history would yield unexpected, even transformative visions when “brush[ed] against the grain.”[2] The example of Frank Pick and his unusual relations with undergrounds personal, aesthetic, and corporate, support this perception: there is often something to be gained from going down the Tubes.

• • •

My fascination with Pick began with a history textbook that cited the Underground’s patronage of modern art. Sentences from undergraduate textbooks are rarely memorable, but this one struck a chord. The notion that modern art could have a social function challenged the standard narrative retailed by my instructors at the time. Many were still invested with the formalist definition of modernism, which maintained that modern art represented a dramatic break with the representational, moral, and utilitarian concerns of art common in the West since the Renaissance. Modern art was self-reflexive and autonomous, untethered from bourgeois norms.

To an undergraduate coming to art history for the first time, the formalist theories explaining modernist works could seem more abstract than the works themselves. I enrolled in a seminar on modernism and soon felt untethered myself, especially by the concept of “significant form” advanced in the writings of Roger Fry and Clive Bell to explain the workings of art in general and abstract art in particular. They argued that art elicited feelings of “aesthetic exaltation” through the internal play of its significant forms, which they unhelpfully described as being “architectonic,” “rhythmic,” and “plastic.” When a classmate innocently queried the instructor about the meaning of a particular cubist painting, she was rebuked for asking the wrong question. “Simply let the play of forms and colors wash over you. Let them take you Somewhere Else.”

For me, Somewhere Else quickly became a course on classical art offered at the same time. But even here I couldn’t escape the bogey of formalist rhetoric. In a darkened lecture hall we were treated to slide after slide of Greek statuary, their significant forms elucidated by a formidable professor waving a lengthy wooden pointer. “Notice the rhythmic undulations of these architectonic masses,” she enthused, her pointer caressing the pectorals of the Kritias Boy. Down the pointer shimmied as she extolled the triangular torso and circular buttocks, the entire design expressive of a tense equipoise between geometric constraint and energetic expansion. “You can see that, can’t you?” she inquired energetically of the darkened room as many nodded in sleep.

During those somnolent moments I never dreamed that so-called formalist art could have practical effects or a social function. Frank Pick’s expressly utilitarian use of modern art therefore appeared anomalous, even perverse, especially since London had been ground zero for the explosion of formalist interpretations at the turn of the century. It was during this time that Fry, Bell, and others in the Bloomsbury Group adapted Kant’s formalist insights into their own aesthetic of significant form, which they used to explain the increasingly abstract works of artists ranging from Cézanne to Picasso. Fry united the disparate works under the inclusive term “post-impressionism,” and publicized them, and the new aesthetic theory, in the controversial “Manet and the Post-Impressionists” exhibition of 1910.

The show generated a famous line from Virginia Woolf, her hyperbolic claim that “on or about December 1910 human character changed.” She should have included an opt-out clause for the English, at least when it came to art: although post-impressionism as a term was rapidly accepted in England, post-impressionist works were not. Public museums did not display them; those few galleries that did were accessible only to a minority. The Bloomsbury Group’s emphasis on significant form was also highly controversial. Indeed, I was to learn that many in England rejected the formalist aesthetic as being suspiciously “cosmopolitan” (by which they meant “French”), while celebrating British art for adhering to utilitarian and moral functions.

Some offered an alternative definition of art more in keeping with these traditions, one that combined “significant form” with “fitness for purpose.” In the 1840s, the architect Augustus Pugin revived the latter phrase, which had been used in the classical and medieval periods to define art in terms of skill, utility, and morality. Just as God had thoughtfully created forms in nature that were fit for their purposes, so too should art reflect the thought and skill of the artisan; just as God had intended his creation to be good, so too should human art serve a beneficial purpose. Pugin’s call for architects to restore the medieval spirit of art as devout and thoughtful workmanship led to the mid-century Gothic revival. His successors John Ruskin and William Morris also hoped that the alleged organic unity of the medieval world might be restored through art created in this spirit. Both soon became disillusioned, however, finding that no soulful art could be sustained under industrial capitalism. Political and social change, they concluded, would have to precede aesthetic change.

However, several of their successors at the turn of the century were more optimistic that society could be transformed by works of art fit for their purposes. Walter Crane, W. R. Lethaby, William Rothenstein, J. R. Sedding and others insisted that society could be improved morally, aesthetically, and economically by integrating “living art” with modern industry. If artists were hired by modern industry as designers, everyday commodities would become the new “common art” sought by Ruskin and Morris. By diffusing these products widely, the public would become aesthetically discerning, the nation more beautiful, and (almost as an afterthought) English exports more competitive. As J. R. Sedding proclaimed, “Fancy what a year of grace it were for England, if our industries were placed under the guidance of ‘one vast Morris’! Fancy a Morris installed in every factory. … The battle of the industries were half won!” Prominent artists, critics, government officials, and educators promoted this new definition of modern art as combining “significant form” with “fitness for purpose.” Many of them worked closely with Frank Pick to challenge the formalist aesthetic, as he was in a uniquely influential position to turn their dreams into reality.

All roads seemed to lead to the Underground. I eventually ended up at the London Transport Museum, still perplexed by modernism. But I was even more curious about this Mr. Pick.

• • •

Pick’s spiritual commitments and utopian dreams were evident from his earliest writings. He was born in 1878 into a lower middle-class family and grew up in the northern city of York; he would always identify with the industrial and commercial values of the North, in contrast to Bloomsbury gentility. These values were balanced, and at times outweighed, by the aesthetic aims of the Arts and Crafts movement and the democratic reformism of Christian socialism. Raised as a Protestant, Pick thought of himself as a “Christian agnostic,” although many others saw him as a self-righteous puritan. (In fact, one reason he was drawn to abstract art was because of its iconoclasm. It seemed the ideal art for Protestants, eschewing the transient world of appearances in favor of the eternal rhythms and universal forms underlying existence. Others brought up as Protestants, such as Roger Fry, Roland Penrose, Charles Holden, and Samuel Courtauld, promoted the new art for similar reasons.)

In several talks he gave to the local Salem Chapel Guild as a youth, Pick preached that the modern urban world required new forms of corporate and spiritual identity. He longed to establish a “City of Dreams,” a heroic quest that would require its founders to assume the “armour of righteousness in moments of trial and step forth spiritual giants, the warriors of the kingdom.” He would be such a warrior, wielding art as his implement: “Art might be converted and become a religion of society. It is a social bond and that is what religion means.”

Pick’s utopianism had a more personal impetus as well: he was a profoundly lonely man. Visions of fellowship were his antidote for bouts of “soul solitude.” Throughout his life he had few friends. He could be unpleasantly puritanical. “Dear Frank,” begins a testy letter from his brother Sisson, “I am sorry that you are still worried about my morals.” Paradoxically, marriage to Mabel Woodhouse in 1901 only heightened his sense of isolation. One colleague observed that she had a “pronounced distaste for the normal customs of conviviality”; another described her as a brooding figure who liked to toss meat to the wasps swarming in the garden. At home, Pick seemed trapped in a loveless version of Wuthering Heights. Near the end of his life he reflected that “every relationship with women gone wrong—never a complete or satisfactory one. … A horrible record in retrospect as age comes on. Makes the heart sick.”

He therefore sublimated his energies into his work and his dreams, hoping to reconcile them. He discerned an opportunity when he moved to London in 1906 to work as a statistical analyst for the Underground Group, then a private group of transport companies. Pick believed that the system ought to have a corporate identity uniting its disparate elements, both as an aid to confused customers and as a model of civic unity. His suggestion that art be used to imbue the system with a distinct persona appealed to Albert Stanley, the new general manager of the company, who was to become Lord Ashfield in 1920. Like Pick, Ashfield was a maverick, willing to experiment. Their personalities were complementary: Ashfield was expansive, convivial, adroit at networking; Pick was headstrong, impatient, a workaholic, and a micromanager. Ashfield therefore concentrated on the wider field of finance and politics, leaving Pick in charge of day-to-day management. Pick was free to follow his instincts about the aesthetics of the Underground, provided that the system continued to make a profit.

It was at this point that the corporate Underground became the patron of the aesthetic underground. Pick commissioned the typographer Edward Johnston to design a special typeface that would be used as a unifying symbol throughout the system alongside the famous Underground “bulls-eye” logo, which Pick had helped to design. Johnston too was an adherent of the Arts and Crafts movement and shared Pick’s spiritual conception of art. He successfully fulfilled Pick’s charge to combine the great lettering tradition of the past with the “living art” of the present, his functional, sans serif typeface appearing on all Underground signage starting in 1916.

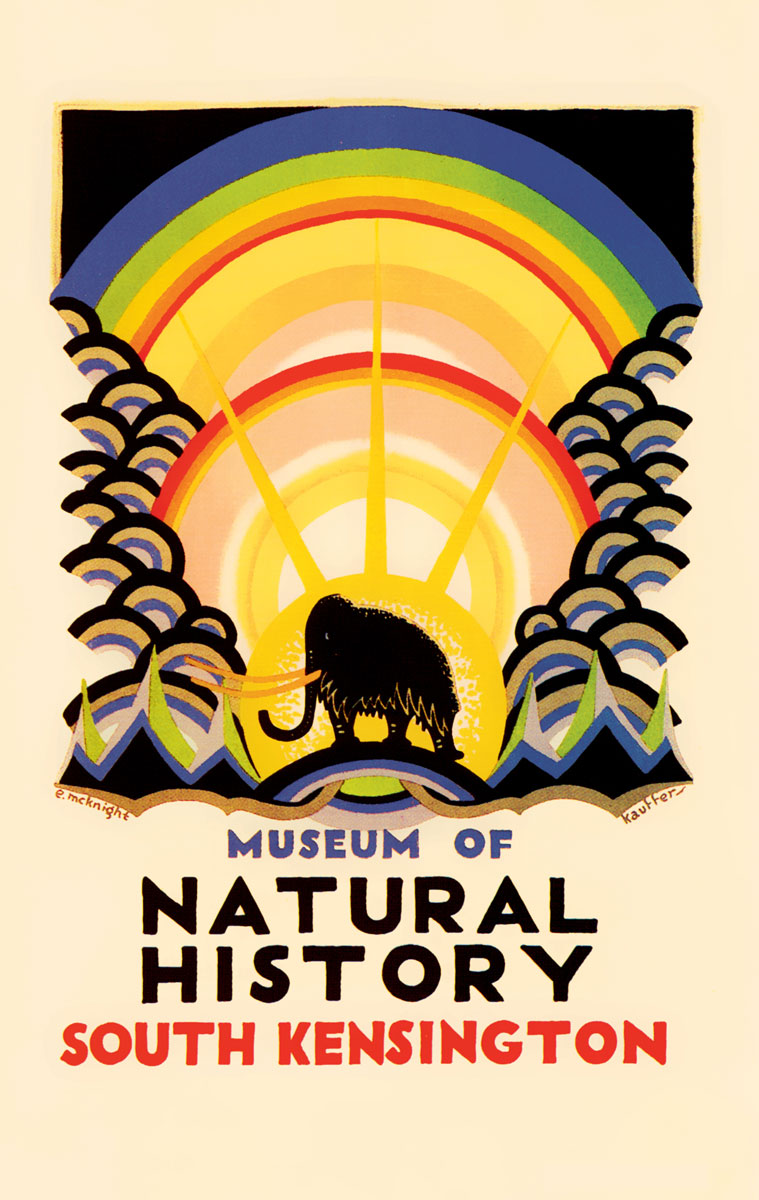

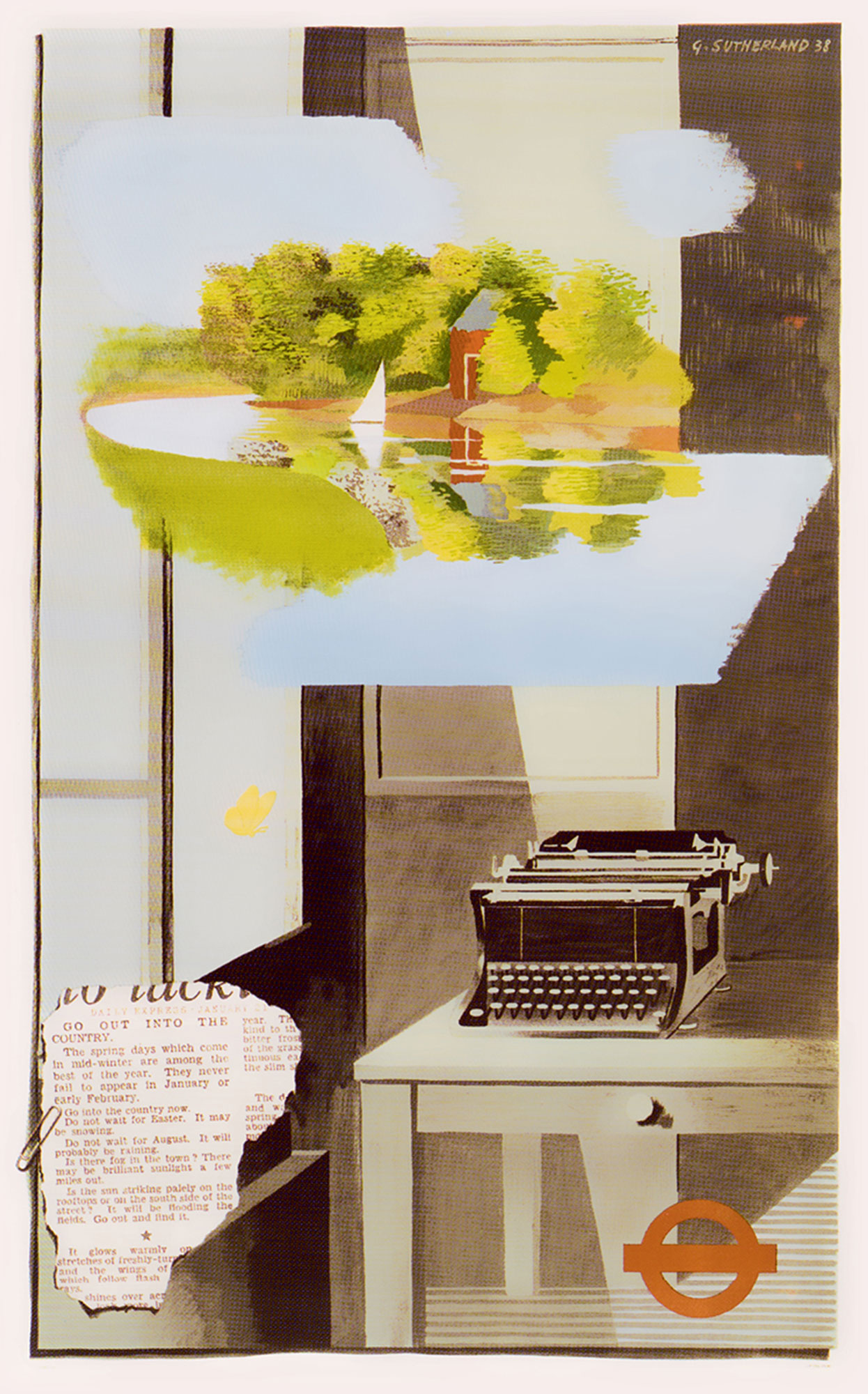

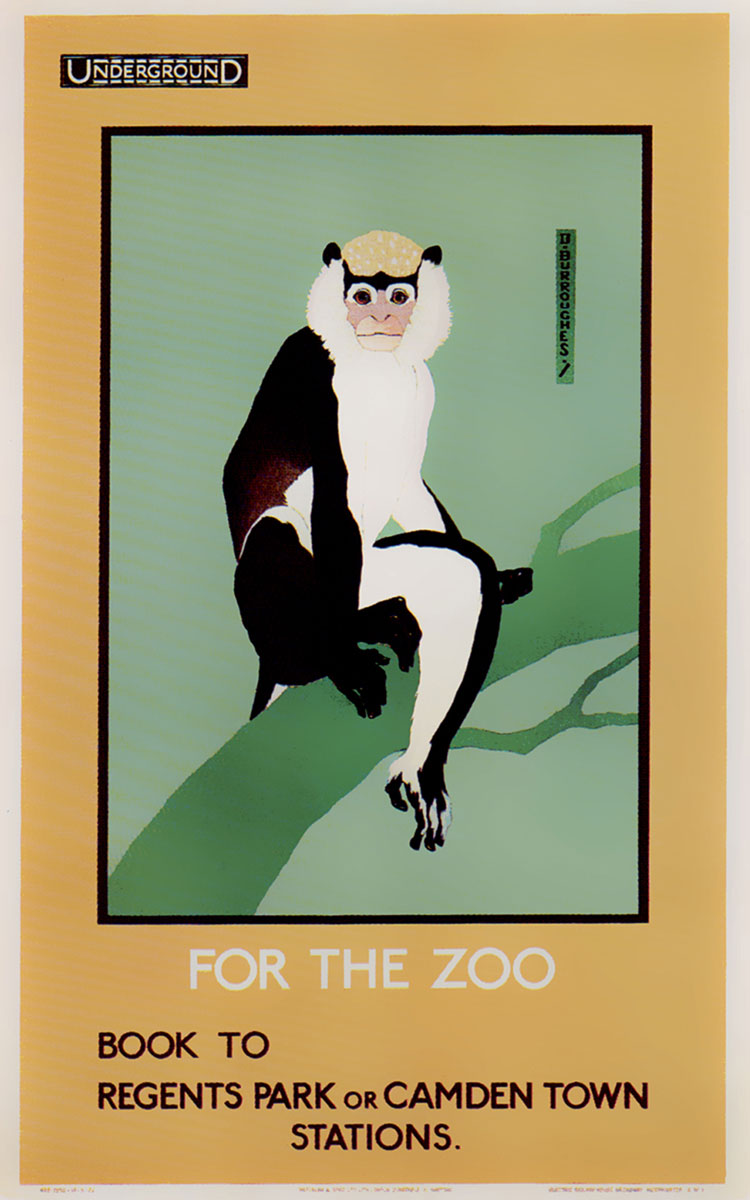

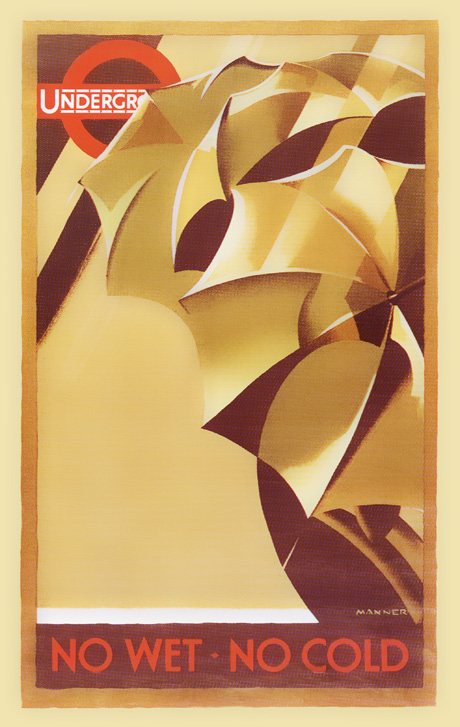

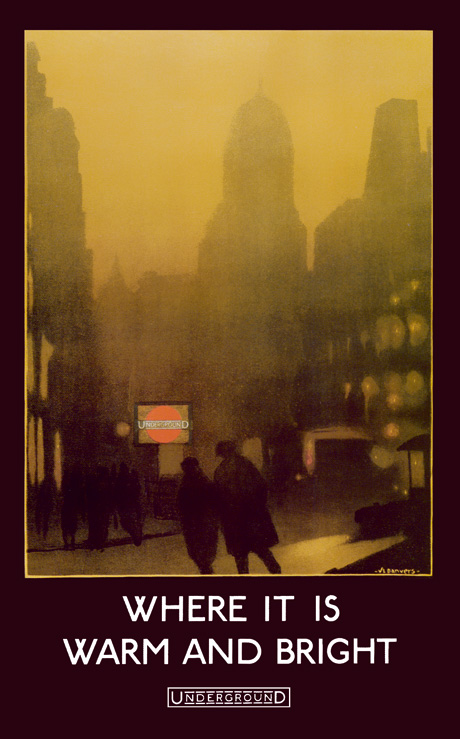

Pick also commissioned modern artists to design advertising posters for the system, as he felt the new artistic styles were especially fit for this purpose. Post-impressionism’s apparent emphasis on clearly delineated, two-dimensional forms and pure colors immediately caught the eye of rushing commuters, and thus was more effective at telegraphing messages than traditional narrative imagery. In addition, the new styles disrupted normative ways of perceiving the world, in Pick’s mind a necessary precondition for the establishment of the City of Dreams: “Posters come to disturb and destroy such habit and convention.” Pick cultivated artists versed in fauvist, cubist, and surrealist styles, highlighting their posters in custom-built display cases throughout the stations. Modernist posters were acclaimed by critics and the public alike, refuting the charge of a prominent advertising executive that “impossible ducks, futurist trees, and such like absurdities” would simply confuse the public. They also generated free publicity, which no doubt pleased Ashfield. One journalist noted that “the art galleries of the People are not in Bond Street, but are to be found in every railway station.”

Other English corporations emulated Pick’s aesthetic program, but not his underlying utopian aims. He was encouraged to pursue these by fellow members of the Design and Industry Association, which had been formed in 1915 to apply the ideals of the Arts and Crafts to modern industry. They insisted that if artists were hired as designers, the ensuing mass-produced products would be works of “industrial art,” the new common art of a commercial age. Everyday commodities would beautify, and vivify, an inert, secular world bereft of sanctity. As Pick stated in a lecture to the DIA, “things are, or ought to be, the receptacles of the spirit of man, and in so far as they are filled with this spirit, they tend to be alive.”

When the Underground began a subway expansion program in the mid-1920s, Pick seized the occasion to fulfill the Arts and Crafts’ aim of integrating art and life. He was emboldened to act by the DIA, which provided him with inspiration and practical support. His radical decision to erect the new Underground stations in a version of the International Style was influenced by the somewhat mystical ideals of W. R. Lethaby, fellow member of the DIA and fellow proponent of “some sense of town sweetness and worship.” Lethaby’s Form and Civilization (1922) had called for a modern school of architecture whose unified aesthetic scheme would function as an environmental catalyst for a cohesive civilization. To create this new style, Pick hired the architect and DIA member Charles Holden; together they settled on a vernacular version of the International Style, combining modernity with local tradition. (For example, Holden used Portland stone, as it had been favored by Christopher Wren, the architect of St. Paul’s Cathedral.) Holden also designed many of the stations’ fixtures, from benches to baskets: the entire transport system was to be a glorious gesamtkunstwerk, a union of the arts not seen since the medieval cathedrals. Pick gleefully acknowledged that “we are going to represent the DIA gone mad.”

Holden’s new stations, as well as his redesign of some earlier ones, were a triumph. A reporter for the New York Times, dazzled by the renovations of the Piccadilly Circus station, found it to be “utterly transformed by modern architecture and modern art into a scene that would make a perfect setting for the finale … of an opera.” It was clear to contemporaries that the Underground had been more influential than Fry and Bell in introducing, and legitimating, modern art to the English public. The DIA’s motto “fitness for purpose” became as apt a phrase for explaining the new art as “significant form.” Holden did not believe the two need be opposed; he declared that “significant form” simply meant “form which is purposeful in all its parts.”

Having established the Underground as an aesthetic corporate entity devoted to social service no less than profits, Pick hoped to use the layout of the expanding system to bestow form to London. The warrior of the kingdom would check unplanned suburban sprawl as well as atomistic individualism through strategic social engineering. “We have to establish a new social synthesis,” he pronounced. “We have to make the warring, conflicting interests of the people serve some commonweal, work in some common fashion. We cannot neglect one great aid to this, which is a city laid out and constructed to embody this end.” He believed that the necessary instruments had been placed in his hands when he was made Vice-Chairman of the London Passenger Transport Board established in 1933. The LPTB brought together all of the underground, bus, and tram companies; Ashfield was Chairman of the Board, and Pick assumed he would be granted the same latitude that he had enjoyed at the Underground Group. He had extravagant plans, exulting that “the metropolitan city is the creature of transport.” The Underground man appeared to be on top of the world. His powers to integrate art and life were extended in 1934 when he became chairman of the government’s newly formed Council for Art in Industry, which was charged with improving the state of the nation’s “industrial art” and art education.

But as a student of scripture, Pick should have known that pride goes before a fall. At the apex of his authority in the mid-1930s, he suddenly found himself descending into a spiritual crisis. He was over fifty; his duties increased as his energy flagged. Further, he did not have as much autonomy in running the LPTB and the CAI as he had anticipated. He was forced to negotiate and compromise, skills he conspicuously lacked. As his visionary aims were rebuffed, he confessed to feeling “quite depressed. ... The weariness of the world and of age begins to beset me.”

One of his greatest disappointments was modern art. He had assumed that it represented the living spirit of the modern age; that once disparate individuals came into contact with its vitalizing rhythms and integrating forms they too would cohere into an organic society. But as artistic movements and styles proliferated, Pick perceived that contemporary art was just another subjectivist expression of modernity rather than a harmonizing spiritual force. By the mid-1930s, this former apostle of the new came to associate modernism with degeneracy: modernism was no longer the god that saved but the devil that deceived. “I have come to the conclusion that practically all modernistic methods are bad,” he wrote in 1934, “and that we must go back a long way and build again on the old foundations. I am certainly not going to encourage modern art anymore myself.” True to his word, when the CAI was put in charge of the British pavilion at the 1937 International Exhibition in Paris, Pick rejected any hint of modernism. The pavilion was a testament to conservatism, and greeted with ridicule. Raymond Williams, cycling through Paris at the time, witnessed “a peculiarly contemptible British pavilion with a large cut-out of Chamberlain and a fishing rod.”

In public, Pick shrugged off the fiasco, but in private he felt disoriented, “afraid of my other activities.” He tried to lose himself in work, as he had always done, but found the only thing lost was his calling. He quarreled with Ashfield and, in a fit of pique, tendered his resignation from the LPTB. To his surprise, it was accepted with alacrity. In 1940 he was without a job, and although acquaintances secured him temporary positions, he was unable to find a new sense of purpose. He considered suicide, describing his existence as a “necropolis.”

Yet he never relinquished his belief that the modern world required religious cohesion, and that art, in its healthiest manifestations, expressed the transcendent spirit that could unite a fissiparous world. Shortly before he died in November 1941, he delivered a talk on “Re-Energizing Religion,” in which he argued that our “plain duty” was “to reconstitute religion and bring back in some ordered relationship all the parts that have gone astray, to restore its wholeness.” Even in the darkness of his spiritual descent he maintained faith in the revitalizing properties of art:

I often visit picture galleries, and when I come out I always know whether I have seen anything worthwhile. You can come out into the drabbest of streets, but if art has been living anywhere within, you will be conscious that it looks just a little different. There will be some subtle sense of colour you missed before, some grouping of objects or shapes which instantly suggests rhythm or pattern. It is a parable.

• • •

The formalist understanding of modernism I learned as a student has since been eclipsed by more contextual explorations of manifold “modernisms.” Today, Pick’s aim of integrating modern art with modern life would align him with many avant-garde artists, including the Russian constructivists, the French surrealists, and the Italian futurists.[3] Yet Pick remains unique, distinguished by the powerful resonances of the word most associated with him. The three meanings of “underground” converged in his life in an unusual way. Pick, however, would not have seen it as unusual: he would have interpreted such a trinity in transcendent terms.

- References for quotations, unless otherwise noted, can be found in Michael Saler, The Avant-Garde in Interwar England: ‘Medieval Modernism’ and the London Underground (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

- Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” in Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings Volume 4 1938–1940, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, trans. Edmund Jephcott and Others (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003).

- Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

Michael Saler teaches intellectual history at the University of California, Davis. He is the author of The Avant-Garde in Interwar England: Medieval Modernism and the London Underground (Oxford University Press, 1999) and co-editor, with Joshua Landy, of The Re-Enchantment of the World: Secular Magic in a Rational Age (Stanford University Press, forthcoming 2009). He is currently writing a history of fictitious people and imaginary worlds from the fin-de-siècle to the present.