Hellbound

To heaven through the bowels of the earth

Alessandro Scafi

At the easternmost corner of the Kaaba, the holiest place in Islam, lies the Black Stone. It was at this sacred spot that the prophet Mohammed met the archangel Gabriel, who took him on a miraculous journey to Jerusalem and then to heaven and hell, a mystical experience that laid the foundation of the Islamic faith.[1] It is believed that the stone was white when it fell to earth at the beginning of time, but turned black because of human sin. Muslim pilgrims to Mecca always attempt to kiss it, as the prophet Mohammed once did. This black stone, and its Eastern position, tell the faithful something about the transcendence of evil, about darkness leading to light.

Echoes of these Eastern events seem to have reverberated in the West. Dante, the medieval Italian poet, describes a journey in his Commedia (1308–1321) from the dark forests of moral depression, through painful purgations, to the maturity of love. His journey takes him through the interior depths of hell where his atonement in suffering leads him to the mountain of purgatory and ultimately to the sacred vision he experiences in the heavenly spheres of paradise. Hell, for Dante, is a necessary and unavoidable stage of his literary journey. Stuck in the midst of a dark and terrifying forest, and unable to rise directly to heaven, Dante is instead drawn deep into the underworld. Only after descending through the infernal regions can the pilgrim move on to discover the nature of meaningful suffering in purgatory and hope for a connection to the transforming energies of paradise. For Dante, hell is the only way to heaven.[2]

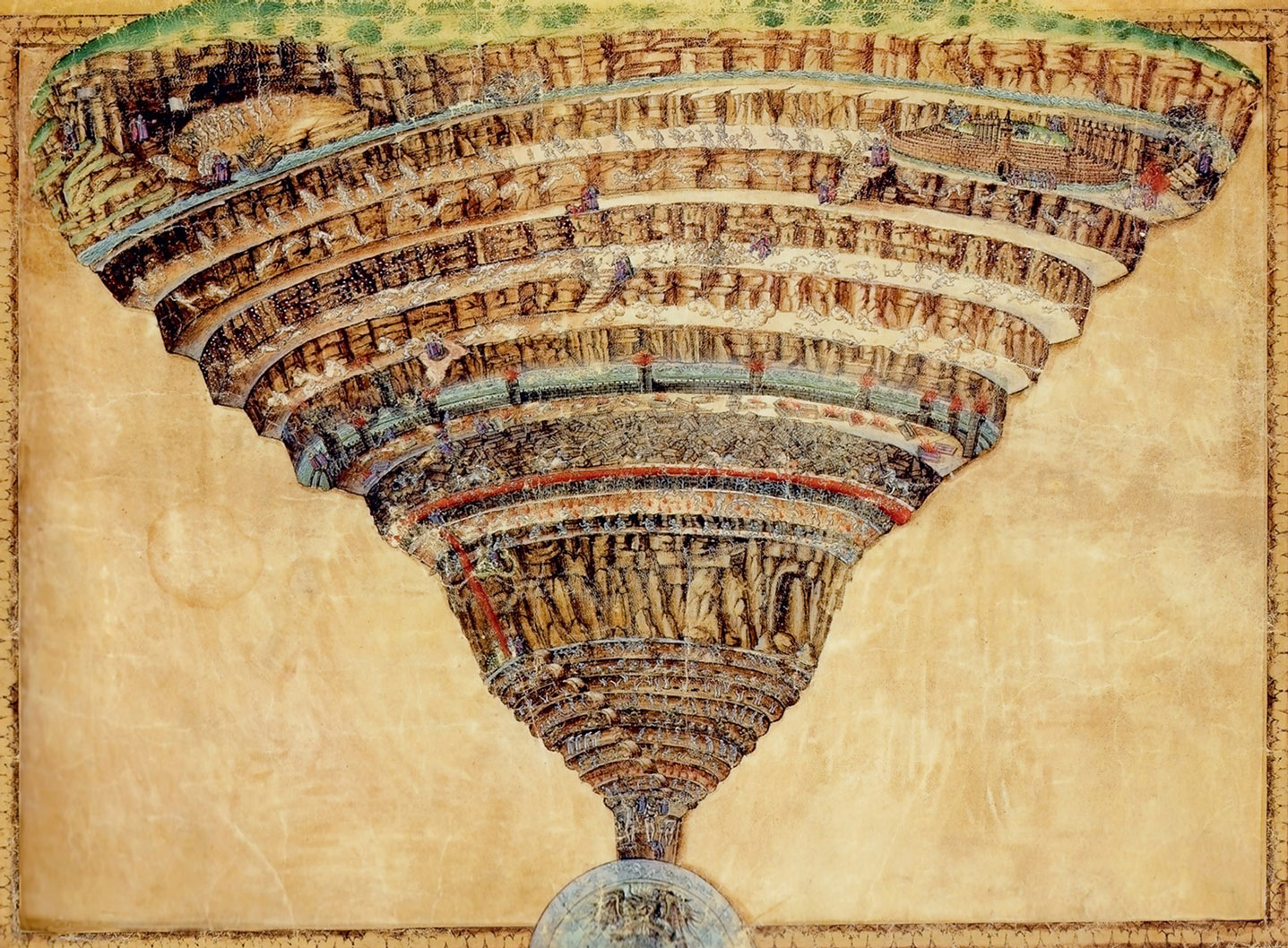

Dante’s underground hell is an inverted, funnel-shaped pit. The descent is ordered in terms of the increasing gravity of the sins that are punished. Those who have indulged their appetites dwell in the upper circle, an inhospitable realm characterized by overpowering wind, filthy rain, and mud—all symbols of uncontrolled passion. The lustful, easily carried away by their passions, are swept around in a whirlwind. The gluttonous, too much fond of eating, are pelted by freezing, filthy slush and flayed by the claws of a barking beast. The hoarders and the spendthrifts, each equally obsessed with materiality, push weights with their chests. The sullen and wrathful, who torture themselves with chronic anger, rage in swampy and dark waters. Sins of aggression and violence, being more intentional and harmful than those of indulgence, are placed in the middle levels, in the burning City of Dis. Those who have engaged in violence against others—tyrants, military conquerors and mercenaries, murderers, and robbers—are immersed in a river of boiling blood, where powerful centaurs shoot arrows at those who dare come up for air. Those who have been violent against themselves, disordering nature and fixating on their despair, suffer eternally in bleeding trees, and those who have been violent against God and against nature are lashed by fiery rain or boil on burning sands.

A greater abyss of more intentional evil is located in the deepest pit of hell, where the fraudulent and the betrayers are punished. The true nature of each sin becomes its own torment and the punishments fit the crime. Seducers and panderers, who pushed their victims around, are forced to move in opposing circles, whipped on by demons; flatterers, who used false praises to deceive other people, flop about in pools of excrement; simoniacs, who used their priestly power for personal gain, are crammed upside down in baptismal fonts and wave their legs in the air as the soles of their feet burn. Diviners, who presumed to be able to look into the future, have their heads placed back to front so that they must walk backwards if they wish to see where they are going. Corrupt officials stew in boiling pitch, and hypocrites are perpetually weighed down with gilded lead cloaks, the mantle of their insincerity. Thieves are transformed into serpents, and fraudulent counselors consumed in fire. Sowers of discord, who failed to recognize the need for wholeness, are repeatedly wounded and split apart by demons’ swords.

In the central abyss of hell an iced river, kept frozen by the chilly blast of Lucifer’s enormous bat-like wings, holds traitors in the icy absence of all human warmth. Only the heads of the lesser sinners emerge from the frozen surface; the worst, at the final level of hell, are completely encased in ice. With the majesty of his perverted evil (his three heads are a mockery of the Trinity), Lucifer protrudes from the ice from the waist upwards and weeps as he chews the arch-traitor, Judas, along with Brutus and Cassius, conspirators against Caesar.

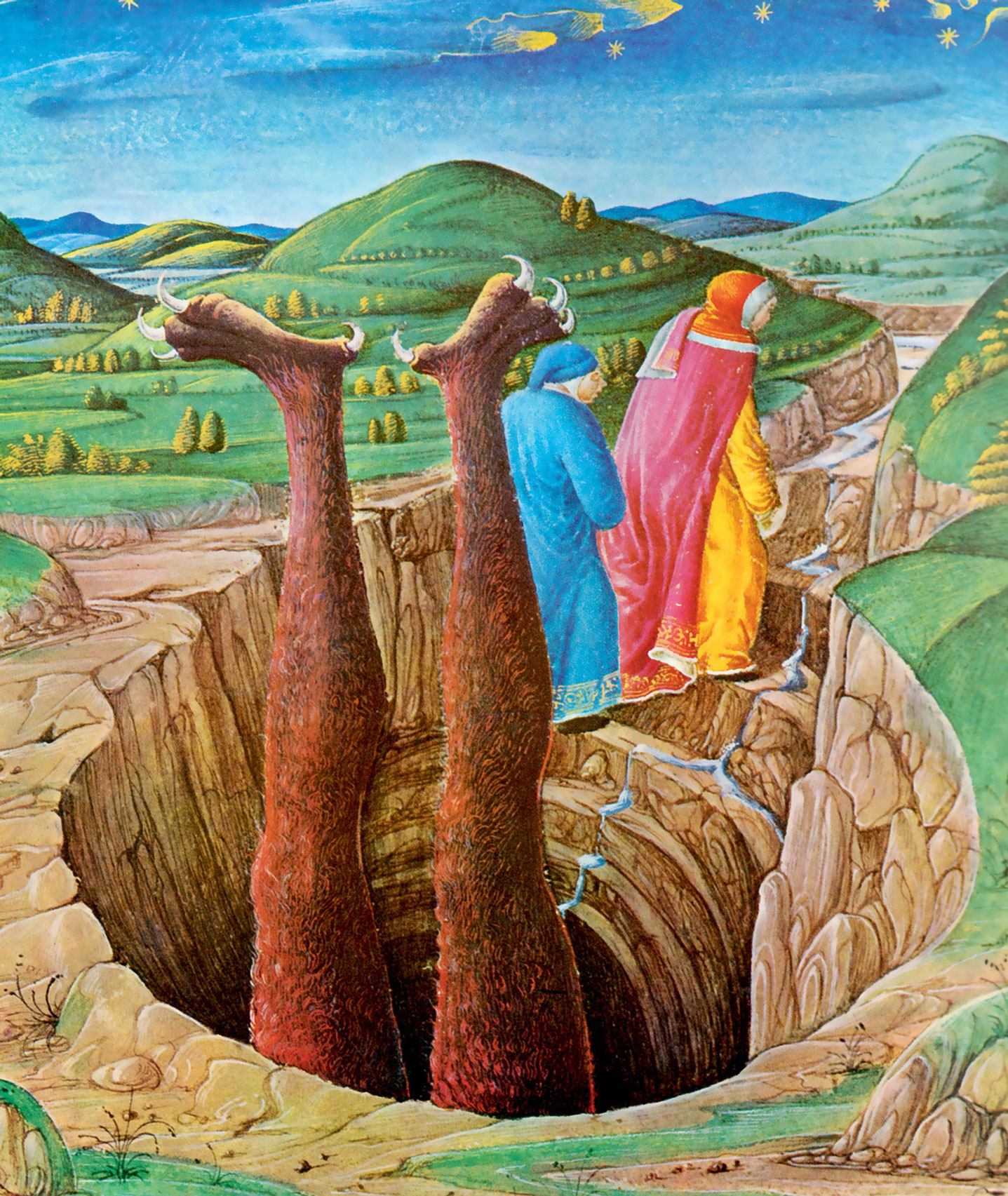

According to Dante, the vast pit of hell is found beneath the northern hemisphere, with Lucifer at the midpoint of the earth. Together with his guide, the Latin poet Virgil, Dante overcomes his terror and manages to make his way down Lucifer’s hairy body, reaching the center of the earth. Then, both the pilgrim and his guide turn upside down and climb Lucifer’s shaggy legs, crawl into an opening in the rocks, and finally emerge, via the tunnel of a long subterranean stream, on the other side of the earth in the southern hemisphere. Beneath the open sky, studded with stars, they find a new atmosphere of hope.

Dante did not create his Christian epic out of nothing. He was a wordsmith who used all the material he had at his disposal. That this included Muslim lore about the afterlife and that Islamic sources entered the structure of Dante’s hell was suggested in 1919 by a Spanish Arabist, Miguel Asín Palacios.[3] Asín Palacios, who intended to show the debt that Dante owed to the Muslim world, pointed out various parallels between Dante’s Commedia and the accounts of the otherworld given in Arabic literature. In his view, the complex moral structure of the Inferno follows the descriptions of hell in the Muslim legends about the afterlife that built up around the Koran and were elaborated by Muslim theologians such as Ibn Arabi of Murcia (1165–1240).

Like Dante’s Inferno, the Muslim hell, according to the Koran, the hadith, and the descriptions of Ibn Arabi, is a dark abyss of great depth, placed beneath the earth’s crust. Muslim tradition also agrees with Dante in imagining hell as a kind of inverted, funnel-shaped pit made up of a series of circles, with the various classes of sinners condemned to a particular torture, and their position in terms of depth linked to the gravity of their sins. The punishments which Dante describes are in a number of instances the same as those set forth in Muslim accounts: serpents devouring sinners, hellish storms, fiery sepulchers, rains and pits of fire, immersion in filth, faces turned back to front, heavy and heated mantles of metal, bleeding wounds, demons armed with sharp swords. In particular, the notion of torture through being subjected to intense cold (not mentioned in the Bible) is found in the Muslim tradition, probably taken from Zoroastrian sources. Finally, Iblis, the Muslim king of evil, lies in the lowest circle of hell, chained in the same manner as Dante’s giant Ephialtes, with one hand in front and the other behind, where he is exposed to the torture of ice (like all demons, he was created from fire and would have been insensible to torture by fire).

Thirty years after Asín’s publication, in 1949, Enrico Cerulli and José Muñoz Sendino provided further evidence in favor of Dante’s indebtedness to the Muslim world, demonstrating the existence of medieval versions in Spanish, Latin, and Old French of the Kitab al Miraj or Book of the Ladder, an Arabic text describing Mohammed’s ascension to the heavens.[4] The thesis that Islamic depictions of the afterlife have been a major influence on Dante’s Commedia has caused great controversy throughout the years, both because it pointed to an Islamic component in one of the greatest Christian epics of all times and because it questioned the originality of the poet’s conception. Asín’s thesis has been rejected by Italian Dantists (with the important exception of Maria Corti), but a general agreement has never been reached. As Stefano Rapisarda has recently pointed out, the controversy over the Islamic sources of Dante’s poem has been fed by national pride and ideological motivations: Asín intended to claim part of Dante’s glory for Moorish Spain in order to promote Spain’s national pride and to favor interreligious dialogue between Christians and Muslims as part of an anti-Bolshevik strategy during the Spanish Civil War, in the same way as today’s renewed interest in the argument in part serves to promote dialogue between world cultures and to question Western monoculturalism.[5]

Even though there might be a political bias to the contemporary interest in Islamic cultural influence on Western society, it is important that Western scholars reassess the role that Islam played in shaping their culture. It has generally been claimed that Europe was born out of the combination of classical and Judeo-Christian cultures, but the Islamic component also needs to be taken into account (as the case of Dante’s hell shows). Moreover, Islamic visions of the afterlife, like Dante’s literary adventure, have something to tell us about going through darkness into light and about the strength that we need in order to live through painful experiences. There are various versions of the story of Mohammed’s miraculous journey. Paradise, however, is always described as a feast of light that the prophet reaches through the darkest of the nights, and his marvelous journey is portrayed as encompassing both heaven and hell.

Similarly, the Kaaba, where the Black Stone is kept, is draped in black, but in their journey towards that black point, the pilgrims are all robed in white cloth. They circumambulate the Kaaba seven times anti-clockwise and, if they cannot reach and kiss the Black Stone because of the large crowds, they simply point at it on each of their seven circuits. The goal of this ritual is to lead the faithful to paradise, just as Dante’s painful experience of the tragedy of evil prepares him for the contemplation of the wondrous otherness of God, which allows him to transcend the stony darkness of the forest of mortal life.

- A rich corpus of legends, in the form of hadith, stemmed from the brief and mysterious allusion to Mohammed’s journey found in the Koran (XVII.1). The earliest versions of the legend include the ninth-century accounts of the Isra (or Nocturnal Journey) and the Miraj (or Ascension). The legend later inspired theological commentaries, literary imitations, and mystical allegories, such as Ibn Arabi’s Book of the Nocturnal Journey (1198).

- For the Catholic Church today, hell is not a site of eternal fire and torment. As Pope John Paul II pointed out in 1999, hell is not a place, but a state of being suffered by the person who lives a life empty of God. Muslim scholars also debate whether Mohammed’s journey to heaven was physical or metaphorical. Dante, however, who set his otherworldy adventure within the physical universe, described hell, purgatory, and paradise as physical places.

- Miguel Asín Palacios, Escatología musulmana en la Divina Comedia (Madrid: Estanislao Maestre, 1919); Islam and the Divine Comedy, transl. Harold Sunderland (London: John Murray, 1926).

- Enrico Cerulli, Il ‘Libro della Scala’ e la questione delle fonti arabospagnole della Divina Commedia (Città del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1949); José Muñoz Sendino, La Escala de Mahoma. Traducción del árabe al castellano, latín y francés, ordenada por Alfonso X el Sabio (Madrid: Dirección General de Relaciones Culturales, 1949).

- Stefano Rapisarda, “La Escatologia Dantesca di Asín Palacios nella cultura italiana contemporanea: una ricezione ideologica?”, in Echi letterari della cultura araba nella lirica provenzale e nella Commedia di Dante, ed. Claudio Gabrio Antoni (Pasian di Prato, Udine: Campanotto, 2006), pp. 159–190.

Alessandro Scafi is a lecturer in medieval and renaissance cultural history at the Warburg Institute, University of London. He is the author of Mapping Paradise: A History of Heaven on Earth (British Library & University of Chicago Press, 2006).