Getting High with Benjamin and Burroughs

Under the influence

Michael Taussig

In the spring of 1932, Walter Benjamin bumped into his old friend Felix Noeggerath in Berlin. Noeggerath was packing to go to Ibiza to join his only son, Hans Jakob, who was studying the language and stories of the island, and invited Benjamin to join him. Ibiza was not only beautiful, unknown, and far from Berlin, but extremely cheap—welcome news for Benjamin, who had by then been reduced to abject poverty despite having been born into a rich Jewish family in Berlin in 1892. Thanks to Nazification, he would lose his apartment in Berlin in three months’ time for “code violations,” and his work for German newspapers, as well as his radio stories for children, would be terminated. His brother Georg, an ardent communist, would be placed in a concentration camp in 1933. Without hesitation, Benjamin accepted Noeggerath’s invitation, thus beginning an exile that lasted until his death from what appears to have been a self-administered overdose of morphine on the Spanish-French border in 1940 as he fled the Gestapo.

Drugs were doubtless important to Benjamin, who had first smoked hashish in Berlin in 1927. They confirmed his approach to reality and revolution, to art and politics—an approach shaped and sharpened by his experience of Ibiza. He stayed on the island two months, returning for another six in the summer of 1933. Wretchedly sad, he buried himself in his remote past, writing of his Berlin childhood. Yet he also wrote in lascivious detail of his surroundings, that other “remote past,” or so it seemed to him, this “outpost of Europe” apparently untouched by modernity. Here, he could face head-on his central idea that modernity atrophied the capacity to experience the world and tell stories. This is why the Ibizan poet Vicente Valero has titled his as-yet-untranslated book on Benjamin in Ibiza Experiencia y probreza (Experience and Poverty), after the title of a little-known essay Benjamin wrote under the spell of the island. In the hallucinatory splendor of Ibiza, with his future cast to the winds, Benjamin formulated what I would count as his major texts—on the storyteller and on the mimetic faculty—as well as inventing new forms for the essay as a crossover genre that linked dreams, ethnography, thought-figures, and storytelling.

Indeed, it is when one turns to this crossover genre that Benjamin’s better-known writings lose much of their obscurity. To read his famous essay “The Storyteller,” for example, is to experience what literary theorist Ross Chambers once confessed to me: “When I read Benjamin I think it is the most brilliant stuff I have ever read. When I finish reading, I can’t remember a thing.” But if you read Benjamin’s own stories, like “The Handkerchief” or his fictionalized account of taking hashish in Marseilles, then in a flash we understand “The Storyteller.”

Valero’s book unhurriedly presents us with Benjamin’s development of a tecnica de viaje (a technique of travel), which involved collecting and creating stories through a mix of “thought figures” governed by a galloping interest in mimesis, a hypertrophied sensitivity to similarities. This is not dissimilar to what Proust was getting at with mémoire involontaire, but this tecnica de viaje was historical and cosmic as well as personal. This Ibizan Benjamin, this storytelling Benjamin, finds himself beached like a whale, a storyteller out of history, practicing what he himself said was dead.

To read Benjamin’s own forays into storytelling is to engage with the excitement of crossing genres and seeing the critic become a practitioner—as with the tales he absorbed traveling third class on the ship Catania for eleven days from Hamburg to Barcelona en route to Ibiza in 1932; tales fertilized by the monotony of ship life, then recreated in another form by Benjamin. There are also the story-like ethnographic episodes that appear in his letters from Ibiza to Gretel Adorno and to his heartthrob, the sculptor Jula Cohn. One letter to Cohn, written on Benjamin’s fortieth birthday and entitled “In the Sun,” was singled out by his friend Gershom Scholem, a life-long student of the Jewish Kabbalah, for its “mysticism” and “poetry”:

It was evident that the man walking along deep in thought was not from here; and if, when he was at home, thoughts came to him in the open air, it was always night. With astonishment he would recall that entire nations—Jews, Indians, Moors—had built their schools beneath a sun that seemed to make all thinking impossible for him. This sun was burning into his back. Resin and thyme impregnated the air in which he felt he was struggling for breath. A bumble-bee brushed his ear. Hardly had he registered its presence than it was already sucked away in a vortex of silence.

This stranger walking along deep in thought was the man who had earlier recruited “intoxication” for the revolutionary cause on the grounds that it could open up the “long-sought image sphere” and thereby innervate the “collective body.” This was the man who in that same essay (“Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia”), published in 1929, two years after he first tried hashish, had warned against the spell of mysticism and drugs, arguing instead for a “profane illumination” that recognized the mysteriousness of the everyday, the everydayness of the mystery. Does “In the Sun” pull this off? Was it actually written on drugs, as Valero suggests, or is it a metaphorical and not an actual intoxication—and does this distinction matter?

The counterpoint to the sun was the moonlight, as in Benjamin’s 1932 note “On Astrology”:

In principle, events in the heavens could be imitated by people in former ages, whether as individuals or groups. ... Modern man can be touched by a pale shadow of this on southern moonlit nights in which he feels, alive within himself, mimetic forces that he had thought long since dead, while nature, which possesses them all, transforms itself to resemble the moon.

Mimesis was fundamental to Benjamin’s theory of language, just as it was, I believe, to his theory of history. In Ibiza, Benjamin fought cat-and-dog with his new friend, the painter Jean Selz, about certain aspects of this theory. Benjamin had recruited Selz to help him translate his Berlin childhood essay into French, despite Selz’s not knowing any German. When Benjamin claimed that the shape of a word was connected to its meaning, Selz exploded: “If the word saucepan looked like a cat in a given language, you would say it was cat.” “You could be right,” demurred Benjamin, “but it would only resemble a cat insofar as a cat resembled a saucepan.”

Even in our time, when according to Benjamin we have lost so much of the capacity to perceive similarity, the mimetic faculty survives vigorously as “the most consummate expression of cosmic meaning,” given to the newborn infant “who even today in the early years of his life will evidence the utmost mimetic genius by learning language.” Mimesis is no less crucial to history itself, as testified in his oracular “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” written shortly before his death in 1940, which combined an anarchist spin on Marxism with Jewish mysticism: “The past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again.” The trick is to “retain that image of the past which unexpectedly appears to man singled out by history at a moment of danger.”

In his two essays on the experience of (just) one night smoking opium with Benjamin high above the port of Ibiza, Selz recalls that Benjamin even coined a special term—the French mêmite—for all of this and points out that for Benjamin this was linked to “a feeling of happiness that he savored with particular care.” (Such jouissance is a significant, no less than puzzling, facet of Proust’s mémoire involontaire, and we might note that Benjamin co-translated two volumes of Proust in the late 1920s.)

What is important about reading Benjamin’s texts written under the influence of drugs is how you can then read back into all his work much of this same “drug” mind-set; in his university student days, wrangling with Kant’s philosophy at great length, he famously stated, according to Scholem, that “a philosophy that does not include the possibility of soothsaying from coffee grounds and cannot explicate it cannot be a true philosophy.” That was in 1913, and Scholem adds that such an approach must be “recognized as possible from the connection of things.” Scholem recalled seeing on Benjamin’s desk a few years later a copy of Baudelaire’s Les paradis artificiels, and that long before Benjamin took any drugs, he spoke of “the expansion of human experience in hallucinations,” by no means to be confused with “illusions.” Kant, Benjamin said, “motivated an inferior experience.”

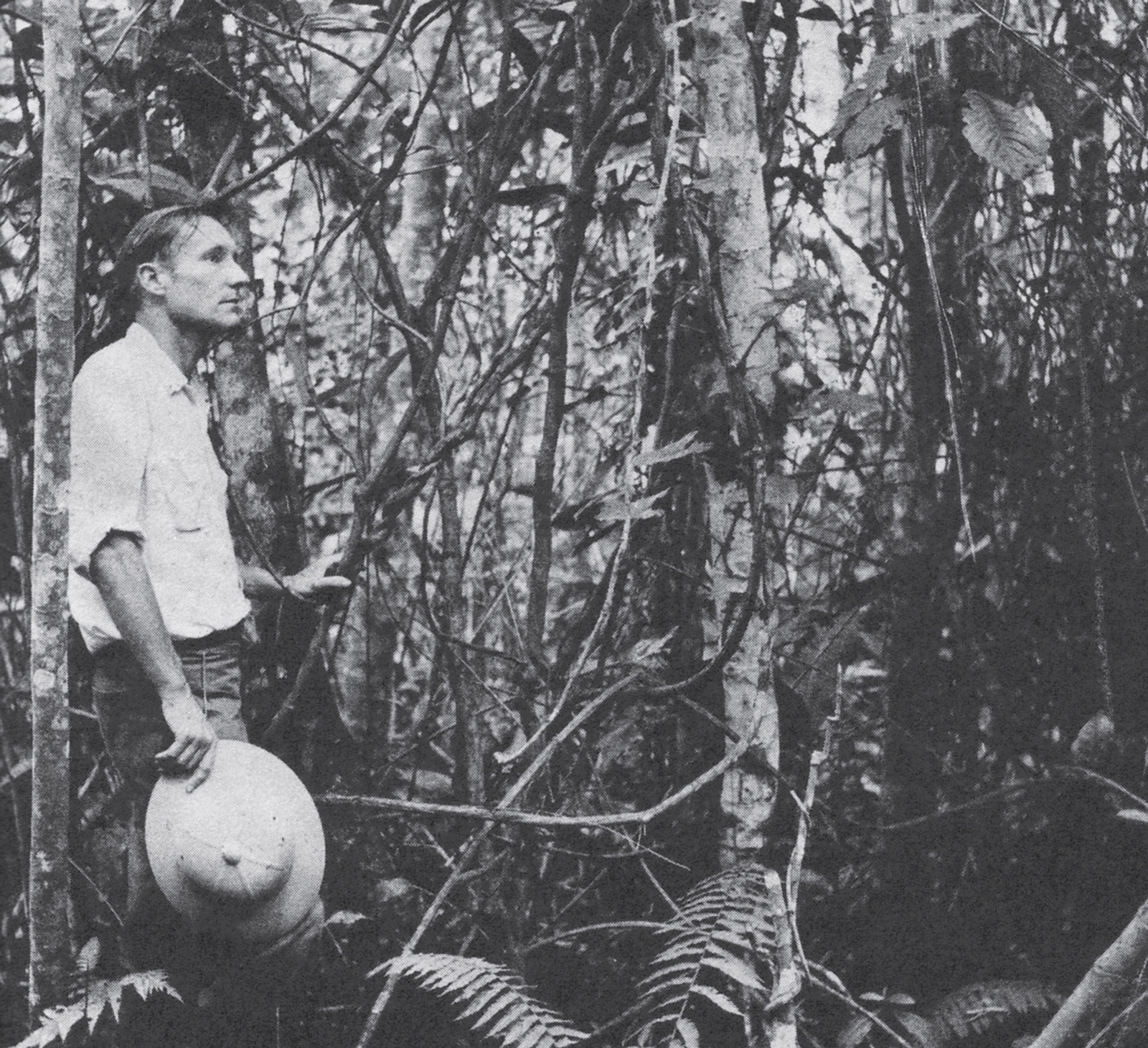

Benjamin’s signature idea of colportage, implying a unity between film montage, walking the city in the style of the flâneur, and drug experiences, was exactly this hallucinatory sense of space-time travel so enthusiastically worked up by Sergei Einsenstein as “plasma” and by William Burroughs as a style of writerly decomposition. For Burroughs, this idea owed much to taking the hallucinogen yagé (pronounced ya-heh; also called ayahuasca in Quechua) administered to him on some seven occasions in 1953 by Indian shamans in the Putumayo of southwest Colombia and in Pucallpa in the Peruvian Amazon. “It is the most powerful drug I have experienced, ” he wrote Ginsberg. “That is, it produces the most complete derangement of the senses.” Yagé provided the seed for Naked Lunch, explained Allen Ginsberg in 1975 in what must be one of the most spirited and generous invocations of Modernism as montage, Burroughs-style, ever made. (see Burroughs Live, Semitotext(e), 2001)

In the fall of 1953, Burroughs, who had recently returned from South America, stayed with Ginsberg on East 7th Street in New York City. Looking out the back window onto courtyards and back windows of apartments, criss-crossed by fire escapes and clothes lines, Burroughs suddenly saw those amazing “composite cities” he had seen when taking yagé, cities that leap at you from all angles and heights throughout his life’s work, as in Cities of the Red Night. What is wonderful is that Ginsberg opens the shutter on that moment when it all came together: New York, yagé, and the wild imagination of William Seward Burroughs, performance artist. “He acted it out completely,” said Ginsberg, “which he always did with his routines.”

As Ginsberg recalls, there on East 7th Street, Burroughs “suddenly had a vision of the racks, the great city of iron racks rising hundreds of feet into the air with hammocks swinging and people climbing from one level onto the other. Over-populated city of racks, where people are stored, just making a living, like they are now in the megalopolis of streets covered with garbage, blocks of ruined buildings, bums living in motorcycle gangs, muggers and policemen and junkies and the CIA stealing out of hallways and blackmailing each other.”

Looking out the window, Burroughs was transformed into a woman reaching out from the upper balconies for her laundry, which became a flayed corpse. Burroughs lunged. “Sometimes he fell on the floor,” Ginsberg continued, “he was so possessed with the total slapstick humor of his imagination, the images that were coming to him almost as a movie picture, automatically.”

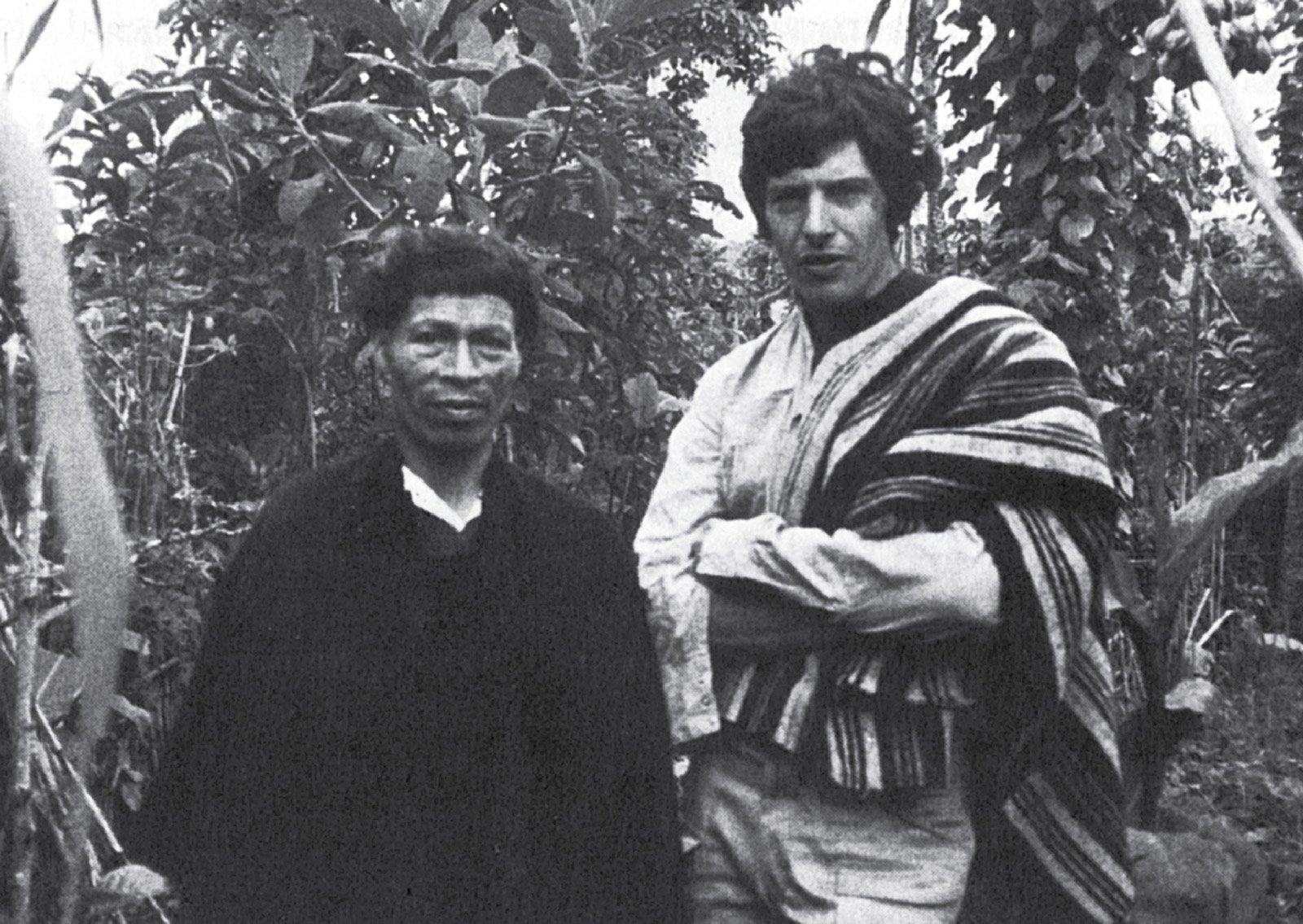

In the recent The Yage Letters Redux (Yage spelled without an accent in the title) by Burroughs and Ginsberg (first published by City Lights in 1963 and now meticulously set in time and place by editor Oliver Harris), we find a parallel to Benjamin’s exploration of drugs and Ibiza. How incredibly exciting it must have been to chase down this awe-inspiring medicine, prepared, sung over, and administered by Indian shamans in the Putumayo forests of South America where, unknown to Burroughs, that other famous homosexual, Roger Casement (later hanged for treason in the Tower of London), had in 1912 gathered testimony as British Consul for his blistering reports on the rubber boom atrocities partially funded by British business. Ginsberg, whose trip occurred in 1960, some seven years after Burroughs’s, comes across as dewy-eyed, naïve, and loving, with tender feeling for his shaman, Ramón, while Burroughs, as American as he is anti-American, is always catty, defensive, offensive, laconic, and absolute master of the put-down. What a pair!

How profoundly different was the courage of this crazy couple compared with today, when yagé, then virtually unknown outside of its forest locale, has become commercialized and tourists are flown in to spend a few days with a “shaman.” The terrible irony, of course, is that The Yage Letters no doubt contributed to the mystique of yagé and its consequent fate at the hands of peddlers of kitsch experience (a substitute for precisely the kind of genuine “experience” that Benjamin saw as imperiled by modern life).

The first edition of The Yage Letters came out of the blue with no explanatory notes whatsoever. What fantasies the reader had to project into it! And now all that has been reversed as the secrets of its origin are revealed when Oliver Harris tells us that these famous letters were not letters at all, but largely made up, except for a knockout piece of writing by big-hearted Allen Ginsberg, discovered miraculously by City Lights editor Lawrence Ferlinghetti in London in 1960. In many ways the “anchor” to the collection, this letter includes Ginsberg’s drawing of the demon Death, and another of the eye of God transforming through Nietzschean Becoming into a holy vagina into which Ginsberg is Dionysically sinking. “Help, Bill! Help!” the un-cool letter from Peru cries out. To which Bill coolly responds from London (in a surprisingly short time) that the way out is the cut-up method and remembering that “‘Nothing is true. Everything is permitted.’ Last words of Hassan Sabbah. The Old Man of the Mountain.”

But what does “made-up”—as in not real but made-up letters—mean for the writer, the cutter-upper, the drug-taker, or the shaman administering yagé, if reality itself is conceived of as really made up? Isn’t “reality” what these writers love to tease? And on the other hand, don’t real letters provide the voice and intimacy, casualness and realness, that the fiction writer thrives upon?

The yagé letters (like Benjamin’s letters to Gretel Adorno and Jula Cohn, which use the form to compose ethnographic sketches) owe something vital to Burroughs’s real letters to Ginsberg from Mexico, Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. As any ethnographer has to admit, the letter form offers powerful advantages in making the strange less strange, thereby turning attention to the strangeness of the known. Burroughs himself insisted elsewhere that the task of the writer is to make readers aware of what they already knew without being aware of it.

In contrast to Benjamin’s drug experiences, the body and death are strikingly present in The Yage Letters. Yet it was Benjamin who was to die in Port Bou, probably by his own hand. It was Benjamin who often contemplated suicide, that “old friend” with whom he was to take a glass of wine in Nice for his fortieth birthday, the same birthday for which he wrote about the Ibizan sun to Jula Cohn.

As with Benjamin’s images of Arabs and Ethiopian hands in his hashish memories, there is in Burroughs “orientalism” galore, conducive to, or at least mixed in with, violent bodily transformations. “Blue flashes passed in front of my eyes,” wrote Burroughs to Ginsberg regarding his first effective yagé trip. “The hut took on an archaic far-Pacific look with Easter Island heads,” while the shaman’s assistant was sneaking around to kill him. Hit by nausea, he rushed to the door but could barely walk. He had no coordination. His feet were like blocks of wood. He vomited violently and then felt numb as if covered with layers of cotton. “Larval beings passed before my eyes in a blue haze, each one giving an obscene, mocking, squawk. … I must have vomited six times. I was on all fours convulsed with spasms of nausea. I could hear retching and groaning as if I was someone else.” On a later trip, he reports to Ginsberg that his body changed into that of a Negress “complete with all female facilities. … Now I am a Negro fucking a Negress.” (This did not make it into The Yage Letters.)

Ginsberg strikes a different note, closer to what I understand to be Benjamin’s “profane illumination,” where he actually celebrates the biting of mosquitoes and the horror of uncontrollable vomiting that yagé induces. At first irritated, he later accepts being bitten as it enables him to feel his body extending into the universe. Along with the barking of dogs and the croaking of frogs, the whine of the mosquitoes becomes part of the song of the Great Being, announcing that Ginsberg, too, will have to become a mosquito as meanwhile the universe vomits itself out.

In his last “letter” from the field to Ginsberg, Burroughs has gotten on top of things and found the necessary concepts—“space-time travel” and “the composite city,” along with yagé-inspired fragmentation, all of which, like money in the bank, shall serve him in his highly original but repetitive writings until the end of his long life. Dated 10 July 1953, this three-and-a-half-page letter pretty much gets it all down, including the last paragraph where he evokes a “place where the unknown past and the emergent future meet in a vibrating soundless hum. Larval entities waiting for a live one.”

This vibrating, soundless hum made me think back to Benjamin’s philosophy of history in which he wrote that “the tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘state of emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule. We must attain to a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight.” The more poetic Burroughs puts the tension of the state of emergency in another mode, that of the vibrating soundless hum.

Both Benjamin and Burroughs wrote from this “state of emergency,” yet as far as I know, Burroughs never read a word of Benjamin. In fact, it would be hard to imagine two more dissimilar people, the one so cultured and polite, so quintessentially European, the other an irascible, sarcastic, hip, and quintessentially American bad boy. But then both WB’s dressed in suits and were massively curious about drugs, mysticism, revolution, film, and cut-up as a method for producing literature no less than for writing history. And then there was color, in which they reveled. Barely a page in Burroughs is not saturated in color, which for Benjamin was what took the child into the image, exactly where Burroughs wanted to be. There was so much they seem to have agreed upon.

Yet it makes you laugh and roll your eyes to think of them having a conversation, perhaps on one of Burroughs’s “color walks” starting off from the Beat Hotel in Paris in the early 1960s. I can see them both now, Benjamin and Burroughs, momentarily stilled, half-way between black-and-white and color in those photographs in my imagination taken by the likes of Giselle Freund and Man Ray. Whoa! The hourglass has not yet run out. Jean Selz has turned up just as we are saying goodbye. For yes, I am there too! I can see myself with an idiotic grin as time and memory pull me this way and that through the different color slides. Such a pleasure to be here with them as they emerge from my pages that, like illustrations in a child’s book, draw me into the scene I depict.

Now Selz has our attention. It is getting dark. The day is fading, as is Benjamin. Time is running out. Selz wants us to remember his friend from Ibiza. He wants us to remember Benjamin’s prose as that truly unique medium, he says, in which poetry and the science of history merge as the truth of the world. What medium is that? I ask. Is it hashish? Is it opium? Is it yagé?

But it is getting dark. There is no reply.

As Benjamin disappears into twilight and Burroughs wanders back to the Beat Hotel, Selz answers my question indirectly, saying that of all the people he knew, Benjamin was perhaps the only one who gave him the impression that there does indeed exist a depth of thought where historic and scientific facts coexist with their poetic counterparts, where “poetry is no longer simply a form of literary thought, but reveals itself as an expression of the truth that illuminates the most intimate correspondences between man and the world.” I like to think that Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs would, as they say, dig that.

Michael Taussig is the author of numerous books, including Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing (University of Chicago Press, 1987); The Nervous System (Routledge, 1992); Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses (Routledge, 1993); Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative (Stanford University Press, 1999); Law in a Lawless Land (The New Press, 2003); and My Cocaine Museum (University of Chicago Press, 2004). He is a professor of anthropology at Columbia University.