A Minor History Of / Useful Corpses

Not all bodies molder in the grave

Joshua Foer

“A Minor History Of,” a column by Joshua Foer, investigates an overlooked cultural phenomenon using a timeline.

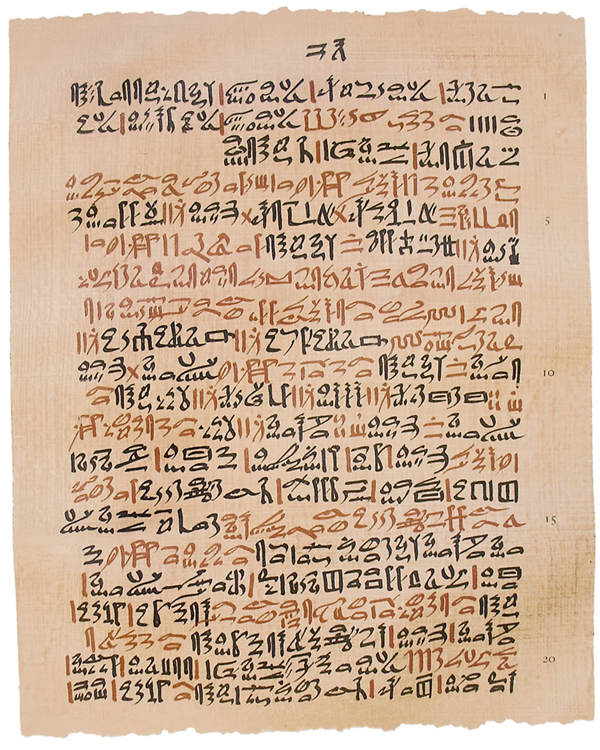

1550 BC

The Ebers papyrus, one of the two oldest medical texts to survive from ancient Egypt, offers the earliest prescription of “corpse medicine” to treat an ailment. For certain diseases of the eye, the text recommends an ointment made from brains of the recently deceased. The tradition of using extracts from the dead to cure the living will remain common in western medicine until the eighteenth century. In treating bruises, for example, the renowned sixteenth-century French surgeon Ambroise Paré proclaims ground-up mummy to be “the very first and last medicine of almost all our practitioners.”

4th century

The twin saints Cosmas and Damian saw off the gangrenous leg of a dying Roman deacon and replace it with that of a recently deceased Ethiopian gladiator. Even more miraculous than this earliest trans-racial organ transplant is the fact that it was supposedly performed by two resurrected saints who had been beheaded nearly a hundred years earlier. It will be sixteen centuries before the next successful cadaverous organ transplant takes place.

1330

The itinerant Friar Odoric of Pordenone returns to Europe with one of the earliest accounts of Tibetan bone artifacts. He relates how priests would quarter a human corpse and feed it to vultures, before fashioning the skull into a drinking cup for family members. Other Tibetan artifacts made of human bones include drums, trumpets, and beaded aprons, all of which are meant to serve as memento mori, or reminders of life’s impermanence.

1586

The English merchant-traveler John Sanderson, visiting catacombs outside of Cairo, reports on the origins of the bituminous umber pigment that came to be known as “mummy brown.” He describes how he grabbed at a collection of embalmed cadavers and “broke off all parts of the bodies … and brought home divers heads, hands, arms and feete”—weighing more than six hundred pounds—which were then sold to European colormen, who ground them up into paint pigment. Though popular among the pre-Raphaelites, mummy brown falls into disuse by the end of the nineteenth century as the supply of mummies runs dry.

1597

A Chinese materia medica describes a “human mummy confection” sold as a topical and oral medication in the bazaars of twelfth-century Arabia. Though mummies are a common ingredient in medieval European apothecaries, the reported concoction seems so gruesome as to almost certainly be apocryphal: “In Arabia there are men 70 to 80 years old who are willing to give their bodies to save others. The subject does not eat food, he only bathes and partakes of honey. After a month he excretes honey (the urine and feces are entirely honey) and death follows. His fellow men place him in a stone coffin full of honey in which he macerates. The date is put upon the coffin giving the year and month. After a hundred years the seals are removed. A confection is formed which is used for the treatment of broken and wounded limbs. A small amount taken internally will immediately cure the complaint.”

1722

Dutch explorer Jacob Rogeveen stumbles upon Easter Island while cruising the southeastern Pacific. Living on an island that is almost entirely deforested and lacking in large mammals, the Polynesian inhabitants there make their fishing hooks out of the most readily available material: the bones of their fellow islanders.

1808

The practice of making cups and bowls out of human skulls goes back at least as far as the ancient Scythians, who were reported by Herodotus to drink from the craniums of their enemies. After fashioning his own goblet out of a skull unearthed on his estate, Lord Byron pens a poem to inscribe upon it. His verse ends: “Our heads such sad effects produce / Redeem’d from worms and wasting clay, / This chance is theirs, to be of use.”

1832

After widespread public outcry over a rash of grave robberies, Britain passes the Anatomy Act, making it legal for doctors and medical students to dissect unclaimed cadavers. Prior to the act’s passage, English “resurrectionists” practice a host of devious methods to snatch fresh bodies during the night. None, though, surpass the infamous Burke and Hare, serial murderers who deliver seventeen fresh corpses between 1827 and 1828 to the Edinburgh Medical College for dissection.

1832

When the philosopher Jeremy Bentham dies, he leaves a will with specific instructions pertaining to the “disposal and preservation of the several parts of my bodily frame.” His skeleton is to be “clad in one of the suits of black occasionally worn by me” and seated upright on a chair, under a placard reading “Auto-Icon.” Bentham suggests that his corpse might then be able to preside over regular meetings of his utilitarian followers. For ten years prior to his death, Bentham purportedly carries in his pocket a pair of glass eyes that are to be embedded into his embalmed head. Here, however, Bentham’s plan goes awry. His face is grossly disfigured in the process of preserving it, and a substitute wax replacement has to be created. The real embalmed head is placed on the floor between Bentham’s legs, where it resides until 1975, when it is kidnapped by a group of students demanding £100 for charity. The university pays £10, and the head of the great moral philosopher is returned.

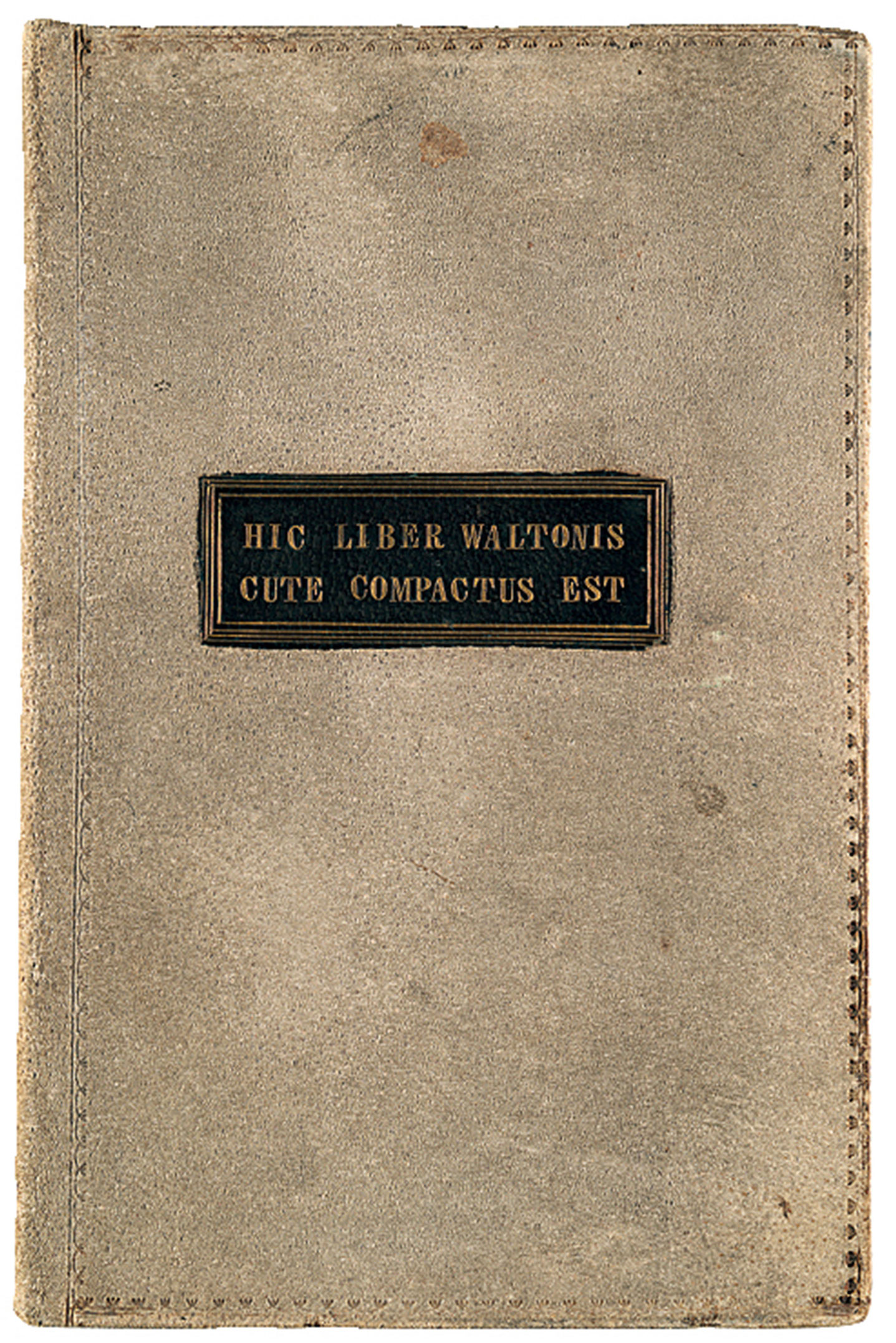

1837

Anthropodermic bibliopegy, or the practice of binding books in human skin, dates back to at least the seventeenth century. Among the most extraordinary examples of this art is a book titled Narrative of the life of James Allen, alias George Walton, alias Jonas Pierce, alias James H. York, alias Burley Grove, the highwayman. Being his death-bed confession, to the warden of the Massachusetts state prison. Walton had always insisted that he was the “master of his own skin,” and upon his execution requests that his memoirs documenting his life of crime and perdition be bound in his own epiderm. Inscribed on the cover are the words “HIC LIBER WALTONIS CUTE COMPACTUS EST”—“This Book by Walton Bound in His Own Skin.” Walton asks that two copies be made. One is to be given to the doctor who attended to him in prison, the other to John Fenno, a survivor of one of Walton’s highway assaults whose courage under fire Walton had particularly admired.

1855

With newspapers proliferating rapidly, the American paper industry is hit by a major shortage of its primary raw material—rags. Dr. Isaiah Deck, a New York geologist and explorer, proposes a remedy in a paper titled “On a Supply of Paper Material from the Mummy Pits of Egypt,” published in the Transactions of the American Institute of the City of New York. Deck calculates that if what he estimates to be the roughly five hundred million human mummies of Egypt were to be disinterred, their linen wrappings could meet America’s paper demands for fourteen years until a more suitable source is identified. To this day, it remains a matter of continuing controversy among historians of papermaking whether Deck’s advice was ever followed.

1870

The Sedlec Ossuary, located in the small town of Kutna Hora in the Czech Republic, was built in the fourteenth century on the grounds of a noted cemetery in order to store the bones of roughly forty thousand people killed by the plague and in various religious wars. At first, the bones were simply stacked inside the church. But in 1870, a local woodcarver named Frantisek Rint is charged with bringing order to the chaos. Rather than simply rearranging the bones, he uses them to redecorate the walls of the church. His pièce de résistance is a large chandelier hanging in the center of the chapel, which contains every bone in the human body. Rint’s signature, in bone, adorns one of the walls.

1881

After escaping from a jail in Rawlins, Wyoming, convicted murderer and train robber George Manuse, aka Big Nose George, is hanged from a telegraph pole by a lynch mob. In order to conduct a dubious study of the criminal brain, a local doctor named John Osborne takes possession of Big Nose George’s body. After examining the cerebral matter, he cuts off large swaths of the criminal’s skin and has them sent to a Denver tanner to be made into a pair of shoes and a medicine bag for himself. Osborne wears the skin shoes often, including on the afternoon in 1893 when he is inaugurated as Wyoming’s second governor. (Photo Scott Burgan)

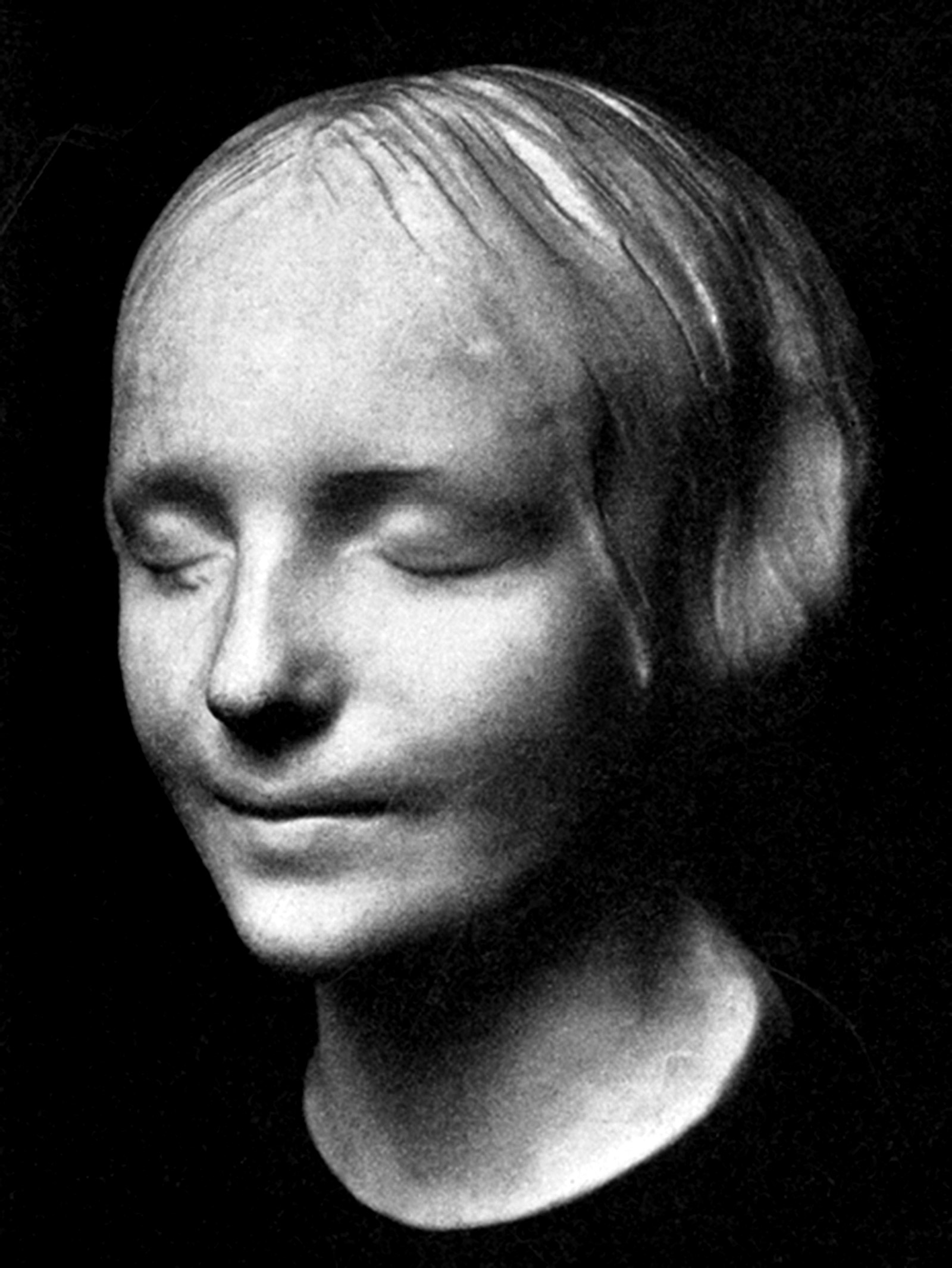

1900

The body of an unidentified young woman, an apparent suicide, is pulled from the river Seine. Enchanted by the mysterious corpse’s beauty, a morgue worker makes a plaster cast of the woman’s face. Copies of this “drowned Mona Lisa,” as Camus would later describe her, soon proliferate across Paris, appearing first in the city’s salons and finally as a character in its literature. Nabokov later writes a poem titled “L’Inconnue de la Seine,” Rilke mentions her in his only novel, Man Ray photographs the mask, and a character in Louis Aragon’s novel Aurélien tries to resurrect her. In The Savage God: A Study of Suicide, Al Alvarez writes, “I am told that a whole generation of German girls modeled their looks on her … the Inconnue became the erotic ideal of the period, as Bardot was for the 1950s.” In 1958, when the creators of Rescue Annie, the first popular CPR dummy, need to put a face on their mannequin, they chose the Inconnue as their model, making her lips perhaps the most kissed of all time.

1945

Among the many heinous crimes of which Ilse Koch, wife of the Commandant of Buchenwald, stands accused is having fashioned lampshades out of the tattooed skin of Jewish victims. When American troops liberate Buchenwald, they photograph a table containing grisly artifacts taken out of the Koch home, including one such skin lamp and a pair of shrunken heads. Until her death by hanging in 1967, Koch maintains that her lampshades were made of animal leather.

1957

After the disappearance of a local hardware store owner, police in Plainfield, Wisconsin, enter the home of Ed Gein and find his farmhouse filled with artifacts made from human body parts: chairs upholstered in human skin, skullcap soup bowls, a table with shinbone legs, a belt made from nipples, and a shirt stitched together from female chests. The legendary psychopath admits to having dug up the bodies of women who resembled his mother and worn their tanned skin as part of a transvestite ritual.

1973

After discovering a mysterious amputated toe in his newly purchased cabin, Captain Dick Stevenson of Dawson City, Yukon invents the Sour Toe Cocktail, an alcoholic beverage garnished with the pickled appendage. The rules of the Downtown Hotel, where the Sour Toe Cocktail is regularly served, state: “You can drink it fast, you can drink it slow, but the lips have gotta touch the toe.” After having seasoned 725 beverages, the original toe is accidentally swallowed by a drunken miner in 1980.

2001

LifeGem becomes the first company to use a high-pressure carbon press to create a synthetic diamond from the cremated remains of a person.

2002

Upon his death, Ed Headrick, inventor of the Frisbee, has his cremated remains molded into Frisbees. Proceeds from the sale of “Steady Ed’s Memorial Discs” go towards the building of a national Frisbee museum in California.

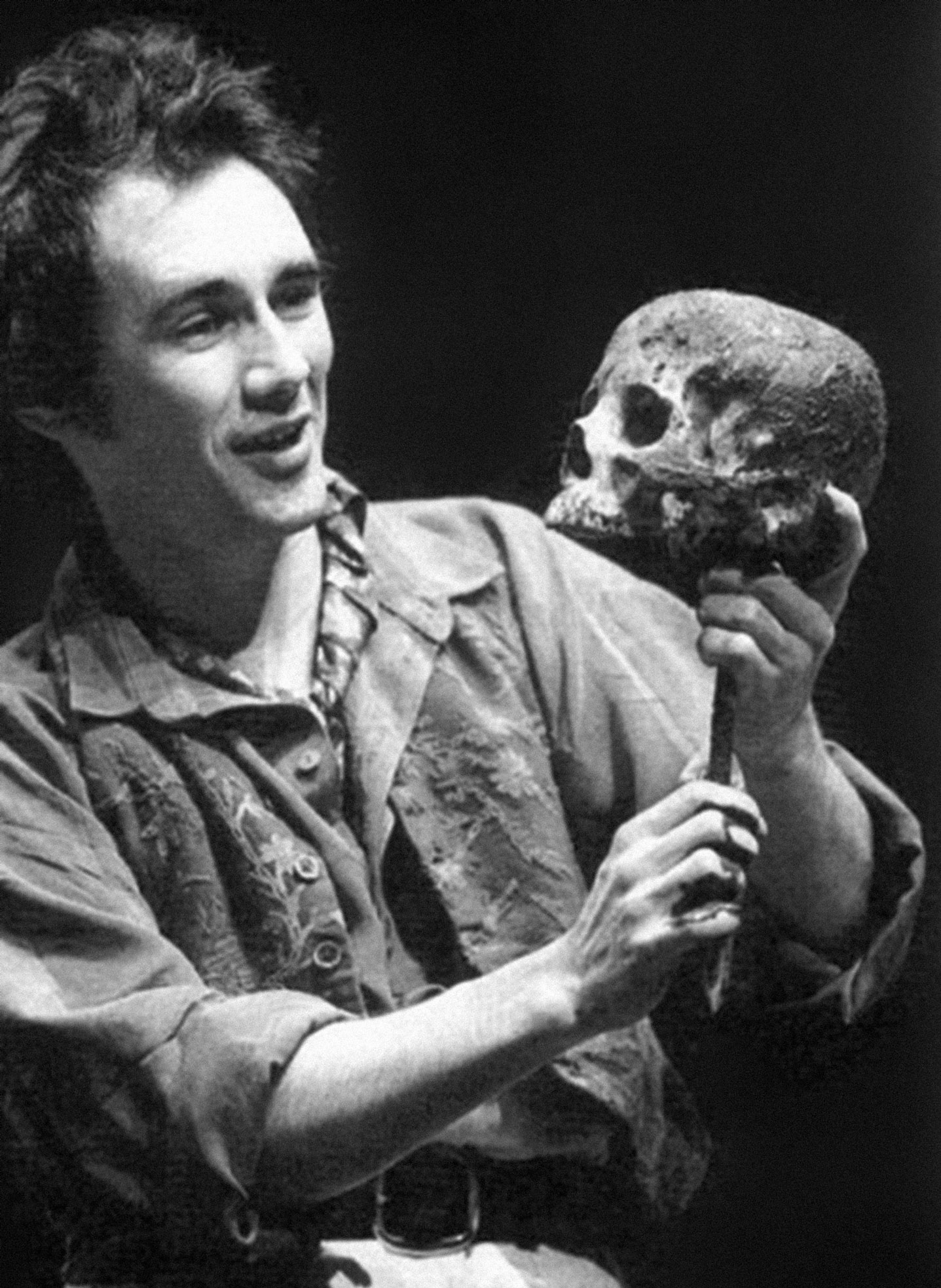

2008

When the acclaimed pianist André Tchaikovsky dies of cancer in 1982, he wills his skull to the Royal Shakespeare Company, hoping that he might someday play the role of Yorick in the company’s production of Hamlet. Twenty-six years later, his wish is fulfilled during a four-month run of the play, though the RSC eventually replaces Tchaikovsky after deeming his skull “too distracting” to the audience.

Joshua Foer is a freelance science writer. He is working on a book about the art and science of memory, forthcoming from Penguin.