A Dry Black Veil

The hovering horror of the plague-cloud

Brian Dillon

By the last decades of the nineteenth century, an obscuring perplex of ideas regarding dust hung above the inhabitants of the European city like overlapping clouds, variously threatening or inspiring with the weight of knowledge, quantity of filth, or degree of infection they contained. London, especially—having only lately escaped a mid-century cholera season that had devastated parts of the inner city—seemed to exist in a miasmic haze of dirt, disease, and curiously aestheticized industrial pollution. As early as 1661, in the pages of his Fumifugium: Or, The Inconvenience of the Aer and Smoake of London Dissipated, the diarist and polymath John Evelyn had complained that citizens breathed “nothing but an impure and thick Mist, accompanied by a fuliginous and filthy vapour,” which concoction scoured their lungs and disordered the entire body, so that coughs, catarrhs, and consumption raged more in London alone than in the whole of the rest of the world. The poison fug was partly attributable to domestic fires, but Evelyn blames brewers, dyers, lime-burners, and salt- and soap-boilers for the most noxious emanations:

Whilst these are belching forth from their sooty jaws, the City of London resembles the face rather of Mount Aetna, the Court of Vulcan, Stromboli, or the Suburbs of Hell, than an Assembly of Rational Creatures, and the imperial seat of our incomparable Monarch. For when in all other places the Aer is most Serene and Pure, it is here Ecclipsed with such a Cloud of Sulphure, as the Sun itself, which gives day to all the World besides, is hardly able to penetrate and impart it here; and the weary Traveller, at many Miles distance, sooner smells, than sees the City to which he repairs.[1]

On arriving in London, avers Evelyn, the visitor in question would discover that a “sooty Crust or Fur” had settled on the city: a veil of dust that was at once obscure and “acrimonious,” “superinduced” on all surfaces and viciously at work undermining the substance of iron, stone, and silver—even sullying the gleam of gold. In the centuries that followed, London became increasingly identified—to the point of a caricature that remained tenacious even after the implementation of the Clean Air Act of 1956—with the particulate soup that passed for a breathable medium among its encrusted streets and dust-heaped squares.

This was the city that the Victorians inherited: layered with the soot of countless coal fires, dusted with the deposits of industry, smeared everywhere with traces of the human and animal feces that fouled the air in dry weather and the feet of pedestrians in wet. (The diversion of this waste into the Thames early in the century was certainly an improvement on the piling up of ordure in streets or cellars, pending its removal by dust-men, but it had the unfortunate consequence of raising a fearsome stench along the river in mid-summer; the Great Stink of June 1858, which caused vomiting among railway passengers at London Bridge station, is just the most notorious instance.) Perhaps even more than the effects of breathing such an atmosphere in public, the Victorian bourgeoisie feared the insinuation of dust into the domestic interior, where it was transmuted from a threat to civic health into the marker of a household in disarray. This is among the more curious fates of dust in modernity: in the public sphere it signifies the depredations of industrial innovation or rising population on buildings and bodies, while in the private realm it continues to denote one’s very lack of modernity, to point to an archaic or shameful inheritance, to signify lassitude or decay. The most vivid (if that is the word) example of the dust-laden domestic setting in the nineteenth century is the phantasmagoria of rot conjured by Charles Dickens in the eleventh chapter of Great Expectations. Entering for the first time the house of the decrepit and reclusive Miss Havisham, Pip eventually reaches her strangely frozen sanctum, a memorial chamber at the center of which sits a long-decayed wedding cake:

It was spacious, and I dare say has once been handsome, but every discernible thing in it was covered with dust and mould, and dropping to pieces. The most prominent object was a long table with a tablecloth spread on it, as if a feast had been in preparation when the house and the clocks all stopped together. An epergne or centre-piece of some kind was in the middle of this cloth; it was so heavily overburdened with cobwebs that its form was quite indistinguishable; and, as I looked along the yellow expanse out of which I remember its seeming to grow, like a fungus, I saw speckled-legged spiders with blotchy bodies running home to it, and running out from it, as if some circumstance of the greatest public importance had just transpired in the spider community.[2]

Dust is here expressly an adjunct to a certain domesticated Gothicism, but the passage can be read too as an example of the fate that might await any comfortable Victorian interior if it were allowed to languish undusted. This is the reading of the overstuffed and intricate nineteenth-century home advanced by Le Corbusier in 1923 in his Vers une Architecture; the comparative emptiness of the Modernist dwelling is designed to discourage the accumulation of dust, and among the architect’s advice to readers concerning air, light, and vacant walls and floors is the instruction to “demand a vacuum cleaner.”[3] For Modernism, to escape the nineteenth century is in part to escape the depredations of dust and the constant intimate attention that it demands to the surfaces and artifacts of the domestic sphere.

• • •

This vision of the recent past as already shrouded in dust acquires, in the works of a more dialectically or perversely inclined Modernism, the lineaments of the fantastic or of an oddly eroticized appreciation of decay. In the section of the Arcades Project entitled “Boredom, Eternal Return,” Walter Benjamin briefly refers to the role of dust in the nineteenth-century interior, a substance at once magical and mundane: “Plush as dust collector. Mystery of dustmotes playing in the sunlight. Dust and the ‘best room.’ ... Other arrangements to stir up dust: the trains of dresses.”[4] In the decaying Paris arcades—the furred arteries of the modern city—dust both occludes and outlines the once-novel commodity and its slow desuetude. For Marcel Proust, too, dust was simultaneously to be feared (in the form of the lime-tree pollen that brought on his asthma, or the choking fumes of the coal fire in his bedroom) and welcomed for the physical and aesthetic veil it cast about him as he wrote; Proust lived his last decade in a cloud of medicinal powders, propped up among material remnants of his past—photographs, books, and furniture—that he refused to allow his servants to dust. And a few years after Proust’s death, in the pages of his journal Documents, Georges Bataille pointed out that the dominion of dust in legend and reality had not yet been properly acknowledged:

Dust, Bataille suggests, may one day gain the upper hand over domestic servants; he pictures a city in which dust has triumphed, “invading the immense ruins of abandoned buildings, deserted dockyards.” In fact, Bataille hints in a fragment entitled “Débâcle,” we may already be living in this grotesque and desiccated dustscape.

• • •

Against the deprecation of dust in the late nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth, an alternative body of scientific and aesthetic knowledge sought to convince of its potential for purity, beauty, and beneficence. In his 1898 essay “The Importance of Dust: A Source of Beauty,” the British naturalist and explorer Alfred Russel Wallace deplored the disease-bearing dust produced by continued reliance on horses for transport and by the coal fires that were still burning at the end of the century, but celebrated for their beauty and utility the atmospheric phenomena that derived from dust:

We find that the much-abused and all-pervading dust, which, when too freely produced, deteriorates our climate and brings us dirt, discomfort, and even disease, is, nevertheless, under natural conditions, an essential portion of the economy of nature. It gives us much of the beauty of natural scenery as due to varying atmospheric effects of sky, and cloud, and sunset tints, and thus renders life more enjoyable; while, as an essential condition of diffused daylight and of moderate rainfalls combined with a dry atmosphere, it appears to be absolutely necessary for our existence upon the earth, perhaps even for the very development of terrestrial, as opposed to aquatic life.[6]

The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa produced such a volume of dust that dramatic and ravishing sunsets followed around the world for up to three years, noted Wallace, for whom the small and “despised” things had in the course of the century revealed themselves as essential adjuncts to the civilization in whose toxic and palling effects they also partake.

Wallace’s scientific appreciation of the ambiguous utility of dust was mirrored in the aesthetic field by certain texts of John Ruskin, perhaps the nineteenth century’s most refined (but also anxious) connoisseur of the cloudy, the gaseous, the particulate, and the friable. With respect to dust, a seam of conventional disparagement runs through Ruskin’s massive oeuvre; in particular, the choking and tarnishing effects of industry and the railroads are frequent themes in his writings. But there are at least two other approaches to dust in Ruskin’s work, both of them visionary, prophetic, attuned to the utopian and apocalyptic possibilities that inhere in earth and air. The first emerges in The Ethics of the Dust, published in 1866 and subtitled “Ten Lectures to Little Housewives on the Elements of Crystallization.” The “housewives” were pupils at Winnington Hall, a girls’ school in Cheshire where, Ruskin reports in his preface, he had actually supervised the lessons in crystallography that make up most of the book. (A good deal of this curious volume is devoted to the author’s spreading of crystals on baize-covered tables and his whimsical efforts to get his prepubescent and teenage audience to form the shapes of various crystals with their own bodies on the grass of the school’s playground.) As Ruskin’s title suggests, the dialogues posit a morality born of the material and metaphorical potential of the earth itself, a deep tendency in the ground beneath our feet (however degraded) toward purity and integrity, and a parallel refinement, as of the crystallization of base matter, in the human heart. Regarding “the lowly framework of the dust,” Ruskin writes:

There seems to be a continual effort to raise itself into a higher state; and a measured gain, through the fierce revulsion and slow renewal of the earth’s frame, in beauty, and order, and permanence. The soft white sediments of the sea draw themselves, in process of time, into smoothed knots of sphered symmetry; burdened and strained under increase of pressure, they pass into a nascent marble. ... The dark drift of the inland river, or stagnant slime of inland pool and lake, divides, or resolves itself as it dries, into layers of its several elements; slowly purifying each by the patient withdrawal of it from the anarchy of the mass in which it was mingled.[7]

The morally inspiring process of crystallization may even occur, notes Ruskin, in “the mud or slime of a damp over-trodden path, in the outskirts of a manufacturing town.” Clay, brick dust, soot, sand, and water: these substances contain the germs of precious stones, porcelain, and the elaborate integrity of snow and ice crystals. Under great pressure and over great tracts of time, they are transmuted into things of fantastic delicacy and strength—Ruskin’s girlish audience is invited to emulate this exalting tendency of dust.

• • •

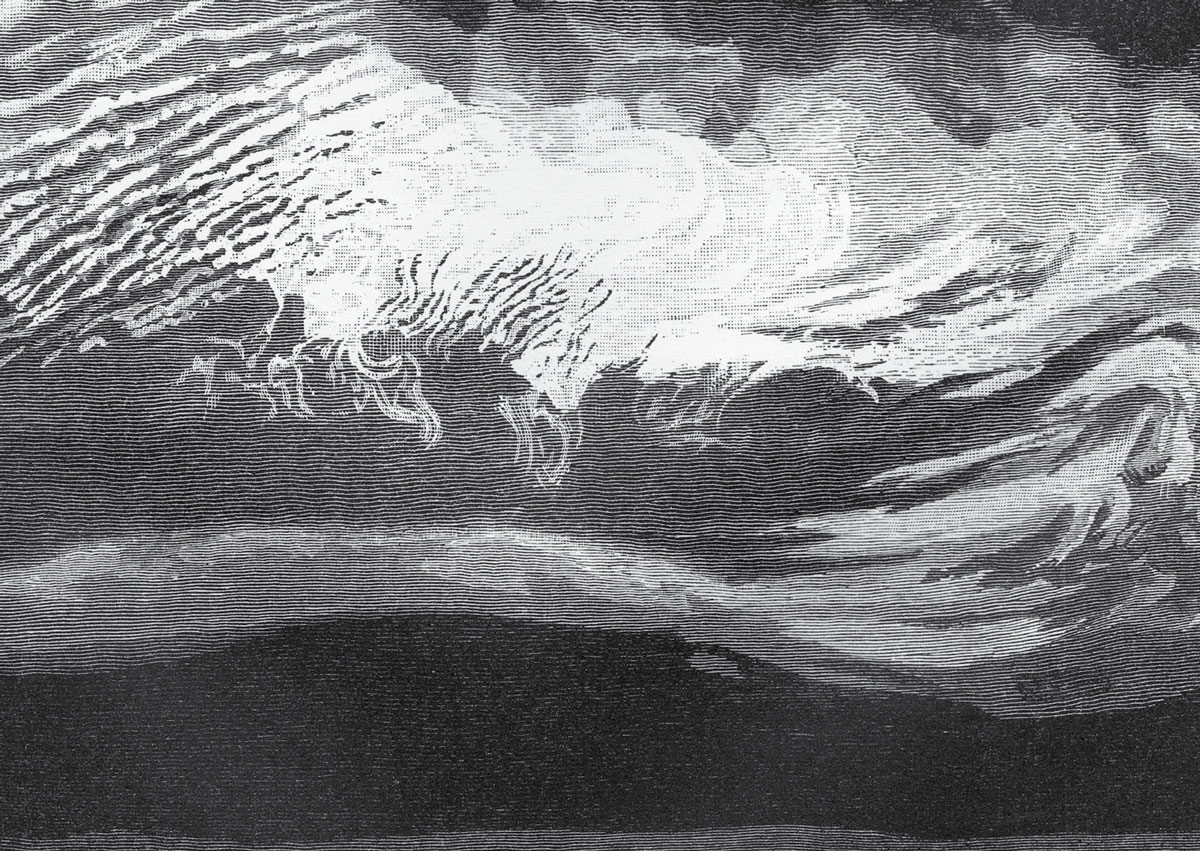

Ruskin had already revealed his ambiguous attitude to base particles in visible profusion in the pages of his Modern Painters, where he variously regrets a tendency towards cloudiness in modern landscape painting and approves indistinction as an aesthetic value: “EXCELLENCE OF THE HIGHEST KIND, WITHOUT OBSCURITY, CANNOT EXIST.” But it was in his late lectures on “The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century,” delivered at the London Institution on the 4th and 11th of February 1884, that he finally tried to face down the modern demon of dust. The first lecture purports to provide its audience with what Ruskin calls an “absolutely true” account of a phenomenon he claims to have been observing for almost twenty years. Something has changed, he writes, in the weather of northern and Mediterranean Europe during that period. A new kind of cloud has appeared: a “plague-cloud,” invariably heralded by a vicious, intermittent wind that seems to blow from all directions at once:

This wind is the plague-wind of the eighth decade of the nineteenth century; a period which will assuredly be recognized in future meteorological history as one of the phenomena hitherto unrecorded in the courses of nature, and characterized pre-eminently by the almost ceaseless action of this calamitous wind.[8]

Neither the cloud nor the ghastly wind that presages its arrival were formerly known to science or poetry; nowhere in the “traditions of air” do Shakespeare, Dante, or Wordsworth speak of the hovering horror that appears to have been recorded for the first time in Ruskin’s own diary, where he kept a sedulous record of its brooding visitations. The cloud is “a dry black veil” that no ray of sunlight can pierce. Ruskin quotes a diary entry from the early 1870s:

It looks partly as if it were made of poisonous smoke; very possibly it may be: there are at least two hundred furnace chimneys in a square of two miles on either side of me. But mere smoke would not blow to and fro in that wild way. It looks more to me as if it were made of dead men’s souls—such of them as are not yet gone where they have to go, and may be flitting hither and thither, doubting, themselves, of the fittest place for them. You know, if there are such things as souls, and if ever any of them haunt places where they have been hurt, there must be many above us, just now, displeased enough! [9]

This last fretful company of ghosts might be a remnant, Ruskin conjectures, of the dead of the Franco-Prussian war, their spirits adrift and troubling the skies from Sicily to the north of England. Its effect on the author himself is to render him also somewhat spectral, an anxious witness who watches the sky and subsequently feels himself dispersed among his own fragmentary diary entries.

This grotesque and opaque effluvium, Victorian successor to the miasma that appalled John Evelyn, is for Ruskin a real meteorological phenomenon; his second lecture is for the most part a defense of the first against the disbelieving and even mocking reactions of the press. But we ought surely to read too in Ruskin’s anguished account of the way the cloud has overcome him in recent years an image of history that contends with Benjamin’s more celebrated motif of the “angel of history.” Like Benjamin, Ruskin sees the rubbish of the world accumulating about him; but where Benjamin’s angel looks dolefully at its feet, the Victorian prophet looks to the sky, because he knows that the atmospheric and historical catastrophe will emerge, like a swirl of dust, out of the air itself.

- John Evelyn, Fumifugium: Or, the Inconvenience of the Aer and Smoake of London Dissipated (London: National Society for Clean Air, 1961), p. 18.

- Charles Dickens, Great Expectations (London: Penguin, 2003), p. 84.

- Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture, trans. Frederick Etchells (New York: Dover, 1986), p. 123.

- Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, ed. Rolf Tiedemann, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999), p. 103.

- Georges Bataille, “Dust,” in Encyclopaedia Acephalica, ed. Alastair Brotchie, trans. Iain White (London: Atlas Press, 1995), pp. 42–43.

- Alfred Russel Wallace, The Wonderful Century (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1899) p. 85.

- John Ruskin, The Ethics of the Dust (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1916), p. 191.

- John Ruskin, “The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century,” in Selected Writings, ed. Dinah Birch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 268–269.

- Ibid., p. 270.

Brian Dillon is UK editor of Cabinet and AHRC Research Fellow in the Creative and Performing Arts at the University of Kent. The US edition of his book Tormented Hope: Nine Hypochondriac Lives (Penguin, 2009) will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux as The Hypochondriacs in spring 2010. A novella, Sanctuary, will be published by Sternberg Press later in the year. He is the author of a memoir, In the Dark Room (Penguin, 2005) and a regular contributor to the Guardian, the London Review of Books, Frieze, Tate etc., and the Wire.