The Art of Movement

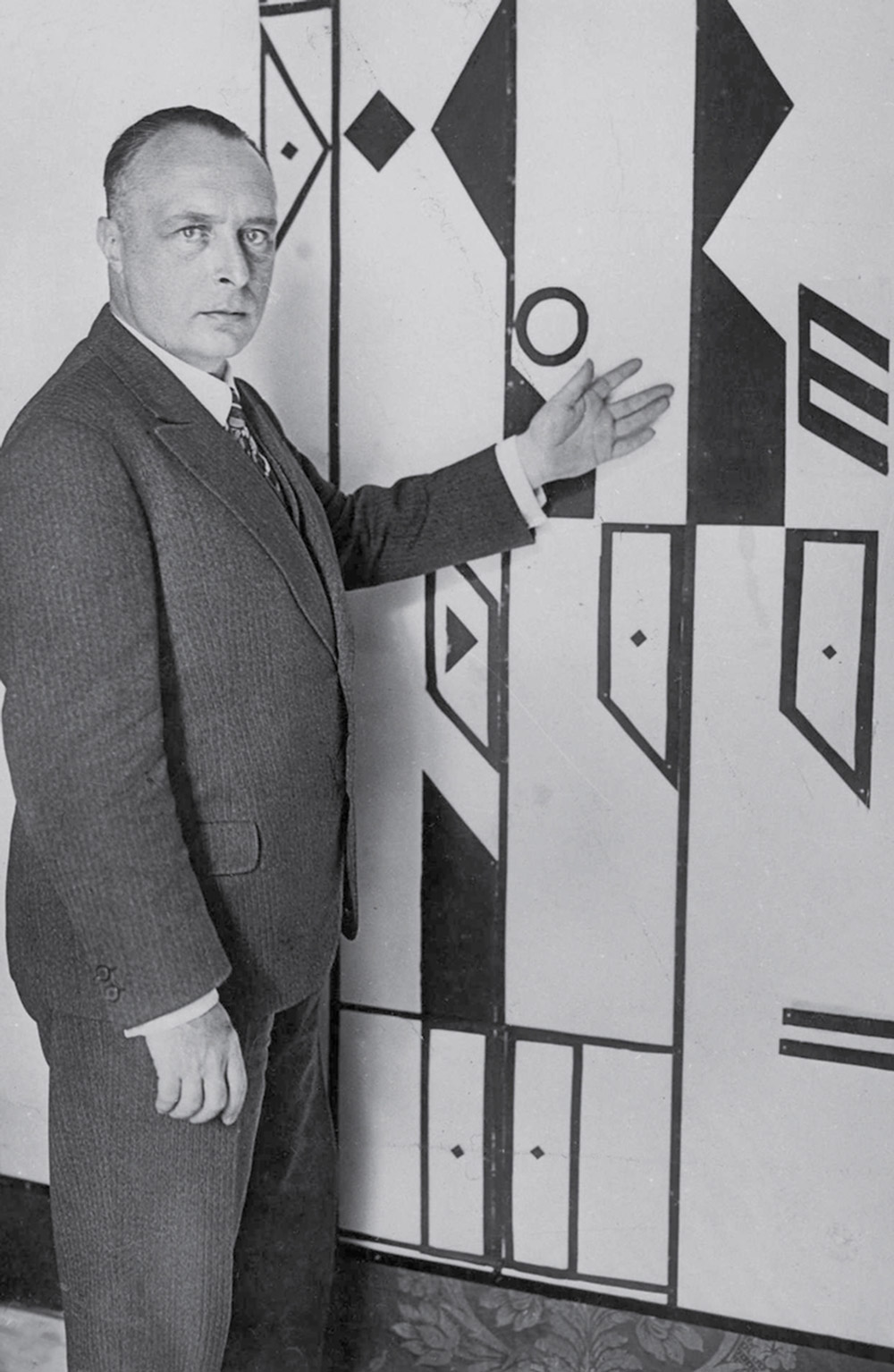

The kinetographic charms of Rudolf von Laban

Christopher Turner

In May 1926, when the choreographer Rudolf von Laban came to America on an ethnographic mission to record Native American dances, a reporter accosted him before he had even stepped ashore. As Laban recounts in his autobiography, the journalist performed a wild tap dance on deck, proffered his starched cuff to the European dance artist, and said, “Can you write that down?” Laban—who had pioneered a new grammar of movement called Kinetography, or script-dance—scribbled a few dance notation signs on the man’s sleeve. The hyperbolic headline announcing Laban’s arrival read: “A New Way to Success. Mr. L. Teaches How to Write Down Dances. You Can Earn Millions With This.” One entrepreneur, tempted by that prospect, tracked Laban down at his hotel and offered him a fabulous amount of money to teach the Charleston and other dances by correspondence course. Laban spurned the get-rich-quick scheme: he did not want to be a part of what he dismissed as “robot-culture.”

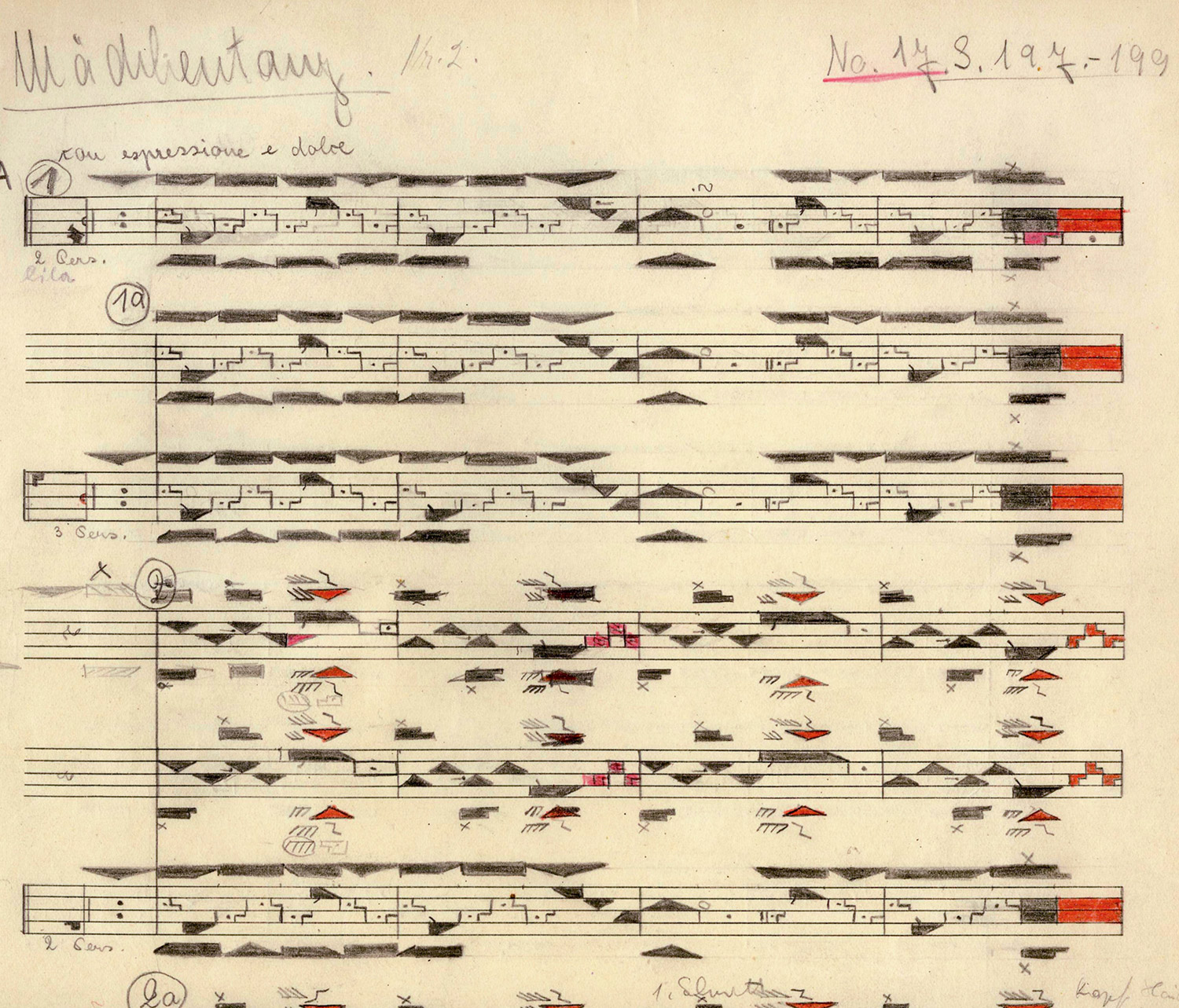

To the untrained eye, Kinetography looks esoteric and occult, but to the few who can read it the complex strips of hieroglyphs allow them to recreate dances much as their original choreographers imagined them. Dance notation was invented in seventeenth-century France to score court dances and classical ballet, but it recorded only formal footsteps and by Laban’s time it was largely forgotten. Laban’s dream was to create a “universally applicable” notation that could capture the frenzy and nuance of modern dance, and he developed a system of 1,421 abstract symbols to record the dancer’s every movement in space, as well as the energy level and timing with which they were made. He hoped that his code would elevate dance to its rightful place in the hierarchy of arts, “alongside literature and music,” and that one day everyone would be able to read it fluently.

Laban, born in 1879 in Bratislava (then a city in the Austro-Hungarian Empire), dropped out of military school to become a painter and moved to Munich at the age of twenty-eight to study choreography. In 1913, he migrated to Switzerland, where he set up an experimental dance school attached to Monte Verità, a picturesque vegetarian sanatorium on a hill near the Alpine village of Ascona that offered “light and air baths” and other nature cures. In his book Mountain of Truth, the historian Martin Green describes Ascona, on the northern shore of Lake Maggiore, as “a nature-cure resort; an artist’s quarter; an international centre of anarchism; a source of Dada; [and] the home of Modern Dance.” Carl Jung, Otto Gross, D. H. Lawrence, H. G. Wells, Herman Hesse, Isadora Duncan, Magnus Hirschfeld, and Franz Kafka spent time there, along with a nonconformist crowd of back-to-nature types, nudists, pacifists, feminists, and libertine philosophers.

Laban, the rebellious, charismatic son of a general, described the “dance-farm” he established there as his “little kingdom”; he would summon his followers each morning by sounding a gong, and they would garden, cook, weave, and make their own clothes, costumes, and sandals. In Empire of Ecstasy: Nudity and Movement in German Body Culture, 1910–1935, the historian of dance Karl Toepfer writes of the radical, frenzied style called Ausdruckstanz that Laban and his group pioneered: “German dance equated the liberated body not with an enhanced power to signify a wide range of emotions but with the power to signify and/or experience a single, great, supreme emotion: ecstasy. The basis for a free and modern identity lay in that most difficult to feel of all emotions.” Ecstasy was seen as a tool to shatter bourgeois conventions, to return the alienated, mechanized modern subject back into harmony with the body, nature, and the unconscious rhythm of life.

There are photographs of Laban dancing in the meadows by Lake Maggiore, surrounded by an Alpine amphitheater: he is a skipping satyr who beats a drum as an ecstatic commune of loosely clad and naked women writhe and leap around him in festive celebration. He was, wrote one of the few men in the bacchanalian troupe, “an alluring Pied Piper, above all a man for women, whose fates he wove into his round dances, insidiously and yet conciliatory.” One of Laban’s dances depicted Ishtar descending to Hades. At each gate of hell, the goddess of love, war, and sex would shed another item of clothing—“the crown of pride, the cloak of hypocrisy, the scepter of violence, the necklace of vanity, the veil of selfishness, the girdle of cowardice”—until she stood naked, shorn of all vanity and egoism, and was welcomed from the other side by a gang of similarly nude and purified souls.

The dionysian aesthetic of modern German dance was heavily influenced by Nietzsche (who Isadora Duncan dubbed “the first dancing philosopher”) and intimately linked to sexual freedom. “It was during this period that [Laban] perfected his strategy of insuring the legacy of his pedagogic ideas by cultivating powerful erotic-physical relations with his female students,” Toepfer writes of the free love that was espoused at Ascona. “He formed a kind of harem of devoted women, demonstrating that Ausdruckstanz involved the construction of a mysterious personality with an almost hypnotic control over the dynamic liberated body.” Though Laban was married to Maya Lenares, an opera singer with whom he had five children, at least two other of his many lovers at Ascona also had children by him.

Mary Wigman, the dancer and choreographer who was Laban’s most famous disciple (and lover), first met her mentor at the Alpine spa in this cult-like atmosphere: “I never quite understood how Laban did it, but he worked miracles on the seriously sick ones,” she recalled, describing an incident when the mesmeric Laban cured a wheelchair-bound woman just by dancing with her. “He was a very good-looking man and, if he wanted to, could be irresistible. But it could not possibly have been his personal charm alone, nor could it have been his easy approach to human nature in general. There must have been something else, a quality even unknown to himself, a super sense of knowledge about the healing powers of movement, which enabled him to help where others had failed.”

It was at Ascona that Laban first experimented with dance notation, which he finessed following World War I—after the Ascona group had disbanded—at the dance school he set up in Hamburg in 1920. In “Choreographie” (1926), his laboratory notebook of that process, Laban documents the fifteen systems he tried. The final one, which borrowed from cuneiform tablets, was an almost utopian alphabet that gave structure to its inventor’s anarchic and communitarian idealism (Anne Hutchinson’s Labanotation from 1954 offers the best key to the cipher). Laban wanted, he wrote to a friend in 1920, “first to give Dance and the Dancer their proper value as Art and the Artist, and second to enforce the influence of dance education on the warped psyche of our time.”

He naively hoped that in the risqué movement-choruses and festivals he choreographed, spectators and participants would be swept up in the dionysian joy of movement, and that corrupt civilization would be regenerated by pagan festivity. One left-wing critic, Hansjürgen Wille, criticized Laban for his “perverted eroticism, pseudo-religious ecstasy, and pedagogical magic, compounded into a doctrine of salvation-through-dance.”

In 1927, while performing the fitting role of Don Juan, Laban had an accident that ended his dancing career prematurely. In the final scene, during which he was supposed to be ripped to shreds by the spirits of hell, he was hurled into the air by the tumult of dancers and crashed to the ground, shattering his leg. “For a dancer to lose his mobility is the same as for a painter to lose his eyesight or a musician to go deaf,” Laban wrote in his 1935 autobiography, A Life for Dance. “Now, more than ever, the value and blessing of notated dance became really clear to me and I began to devote myself with redoubled zest to consolidating and notating my works.”

Now that he was disabled, Kinetography allowed him to dance instead in his mind. In 1928, Laban established the German Society for Written Dance and began to organize dance congresses and publish books on movement theory, establishing himself as the leading authority on dance in Germany. In 1930, he was appointed head of the Prussian State Theaters in Berlin, which were incorporated three years later into Goebbels’s Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda. Laban was required to purge the theaters of all Jewish performers, and he jettisoned his earlier radicalism in the pursuit of grand Nazi spectacle, immersing himself in the choreography of large-scale festivals and pageants for the new regime. His autobiography shows how much his celebration of communitas and nature-worship and his casual racism, mistrust of modern art, and hatred of the corrupt city shared with Hitler’s nationalist ideology.

Laban choreographed a piece for the 1936 Berlin Olympics, “Of the Warm Wind and the New Joy,” that used one thousand dancers to set Nietzsche’s philosophy to music, but he was fired after Goebbels attended the dress rehearsal. “Loosely based on Nietzsche, a shoddy and artificial thing,” wrote Goebbels in his diary. “It is all so intellectual. I don’t like it.” The German cult of the body, of which dance formed a crucial part, is now indelibly associated with Nazi propaganda advancing ideas of Aryan health and superiority. However, it is important to remember that until the Nazis came to power, body culture was just as closely associated with left-wing groups, who saw dance and nude calisthenics as a radical, liberating force. The individualistic aspect of expressionist dance, even in Laban’s attempted collaboration with the Nazi regime, jarred with the militaristic, synchronized routines choreographed by another dancer, Leni Riefenstahl, for her film of the 1936 games.

In 1937, out of favor and expressing his disgust with Nazi philistinism, Laban fled to France and then England, where he found refuge at Dartington Hall, a progressive school in Devon. He spent the last twenty years of his life in England, setting up the Art of Movement Studio in Manchester and refining his movement theories. His methods found an unexpected application in industry, where they were used in management training and to improve efficiency on the factory floor. There are still several Laban schools around the world and, though Kinetography has not become the universal tool that Laban had hoped, hundreds of dances are kept on file in repositories such as the New York Dance Notation Bureau, where the initiated spend up to a year transcribing a single performance into Laban’s special code. The ecstasy of movement Laban embodied is transformed into its apparent opposite: an abstract geometry of carefully ordered shapes.

Martin Green, Mountain of Truth: The Counterculture Begins—Ascona, 1900–1920 (Hanover, NH and London: University Press of New England, 1986)

Dagmar Herzog, ed., Sexuality and German Fascism (New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2005)

Ann Hutchinson, Labanotation: The System of Analyzing and Recording Movement (New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1954)

Lilian Karina & Marion Kant, Hitler’s Dancers: German Modern Dance and the Third Reich, trans. Jonathan Steinberg (New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2003)

Rudolf von Laban, A Life for Dance: Reminiscences, trans. Lisa Ullmann (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Books, 1975)

Vera Maletic, Body, Space, Expression: The Development of Rudolf Laban’s Movement and Dance Concepts (New York, Berlin & Amsterdam: Mouton de Gruyter, 1987)

Susan Manning, Ecstasy and the Demon: The Dances of Mary Wigman (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2006)

Valerie Monthland Preston-Dunlop, Rudolf Laban: An Extraordinary Life (London: Dance Books, 1998)

Karl Toepfer, Empire of Ecstasy: Nudity and Movement in German Body Culture, 1910–1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997)

Christopher Turner is an editor of Cabinet. His book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came To America, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.