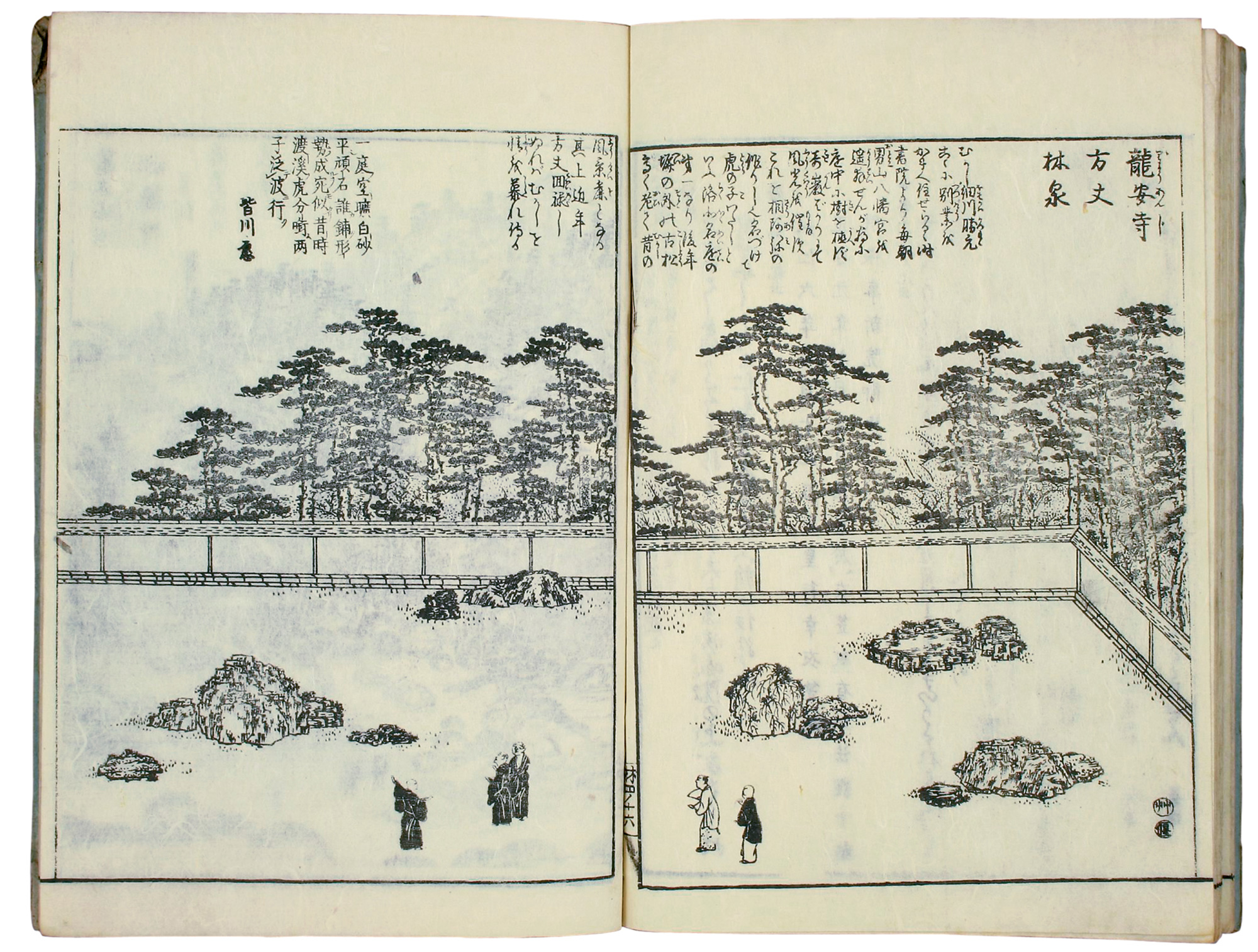

Dry Mountain Water

Afloat on a sea of stones

Allen S. Weiss

The unequivocal focus of the Zen garden is stones. We find stones with stones, stones on stones, stones representing mountains, stones crushed to gravel, and often just single exceptional stones that all by themselves constitute a landscape. In Chinese and Japanese cosmology—be it Taoist, Buddhist, or Shinto—stones are not mere inanimate objects, but rather concentrations of cosmic and telluric energy (ch’i) flowing in different patterns throughout the universe. Zen master Dogen insisted that pebbles are sentient beings that participate in Buddha’s nature, and such age-old theories of panpsychism have recently been reconsidered on the subatomic level by contemporary science. One theory suggests that “the rock’s innards ‘see’ the entire universe by means of the gravitational and electromagnetic signals it is continuously receiving,” and further proposes that “if you are poetically inclined, you might think of the rock as a purely contemplative being.”[1] In short, agency is distributed everywhere in the universe.

The Chinese love of rocks may even be surpassed by that of the Japanese, who have declared certain famous stones to be national treasures. One of the classics of Japanese landscape art, the priest Zōen’s fifteenth-century Illustrations for Designing Mountain, Water, and Hillside Field Landscapes, enumerates 57 types of rocks, reduced from the 361 of Chinese tradition, and from the thousands in certain Indian manuscripts. Rocks are categorized into types according to structure, function (scenic and sensory effects), and symbolism (Taoist, Shinto, Confucian, Buddhist): side rocks, lying rocks, wave-repelling rocks, water-cutting rocks, stepping stones, shadow-facing stones, ducks’ abode rocks, hovering mist rocks, human form rocks, mirror rocks, reverence rocks, demon rocks, vengeful-spirit rocks, taboo rocks, triadic Buddhist waterfall rocks, etc.[2] Specific rocks may symbolize mountains, both mythological and real, most often Mount Fuji. Rocks may represent other natural objects as well, like the waterfall rocks (taki-ishi) common in Zen gardens, so named because their vertical surface patterns suggest cascading water. Notable rocks are often given names, such as Twofold World Rocks, Rock of the Spirit Kings, or Dragon’s Abode Rock.

Bernard Rudofsky makes a good point (his sarcasm notwithstanding) in claiming that “maybe we ought to envy the imaginative powers of a people who can distinguish rocks by 138 names (if only two sexes); that will court and covet rocks of special appeal, kidnap them, wrap them in silks and brocades like the most precious of sweethearts, and carry them in triumphal procession to their new abode.”[3] He is obviously referring to a specific moment in Japanese history when Nobunaga, a powerful warlord, had a rock garden created for the last Ashikaga shogun at one of his palaces in Kyoto. Regarding the transfer of a particular rock from one garden to another: “Nobunaga had the rock wrapped in silk, decorated with flowers, and brought it to the garden with the music of flute and drums, and the chanting of the laborers.”[4] At the other extreme are, according to Zōen’s Illustrations, the “unnamed,” “worthless,” or “discarded” rocks, ones that do not have the specific characteristics that warrant names, but that are nevertheless essential in the composition of the garden, whether to enhance the naturalness of the formal composition, to create dynamic balance, or to highlight a more prominent stone.