What Is There to Be Learned from Kitsch?

Walter Benjamin and the “furnished man”

Brigid Doherty

For art historian Gustav Pazaurek, kitsch provided an object lesson in bad taste and a fitting subject with which to demonstrate the cultural function of the museum of applied arts as an institution of public education in early twentieth-century Germany. While serving as director of the Landesgewerbe Museum in Stuttgart in 1909, Pazaurek installed an exhibition of “Errors of Taste in the Applied Arts” that drew large numbers of visitors and significant interest from the German as well as the international press. By 1919, when Pazaurek published the third edition of his guide to the ongoing “Errors of Taste” exhibition, he could cite enthusiastic press coverage from Budapest to Boston to Buenos Aires, as well as several exhibitions elsewhere in Europe that were modeled on the Stuttgart installation.

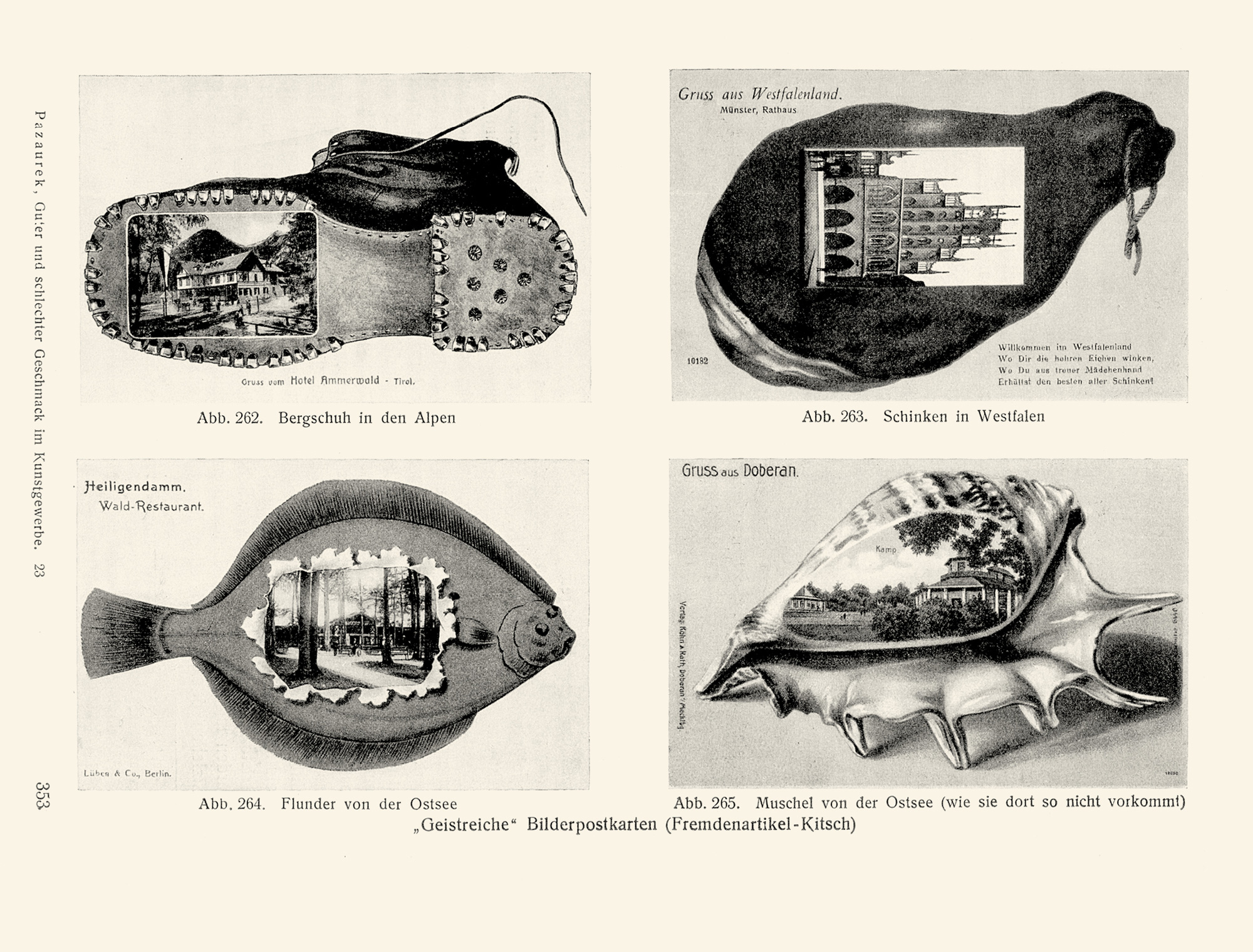

The final chapter of Pazaurek’s 1912 book Good and Bad Taste in the Applied Arts, a comprehensive discursive counterpart to the museum exhibition in Stuttgart, is called simply “Kitsch.” Having introduced kitsch as the “shadow side of the tremendous development of large-scale industry in the nineteenth century,” Pazaurek goes on to provide a catalogue of early twentieth-century kitsch, from patriotic Hurrakitsch and religious Devotionalienkitsch to the Reklamekitsch of advertising and the Aktualitätskitsch of contemporary events, as well as the ever-present Geschenkkitsch, the last a category of things to be purchased for obligatory gift giving in honor of occasions great and small. Among the many objects of Geschenkkitsch whose ubiquity Pazaurek laments are the novelty picture postcards mailed by friends or relatives who will soon return from their travels bearing yet more gifts of souvenir kitsch in other forms. Kitsch, as Pazaurek saw it, had emerged in the period following German unification not only as an embodiment of bad design and cultural decline but as a medium, indeed an agent, of the debasement of communication.

Pazaurek’s didactic curatorial campaign against bad taste was connected both to the promulgation of reform in industrial design and architecture by the Deutscher Werkbund and to efforts to educate a broad middle-class public undertaken by organizations including the Dürerbund, whose founder, Ferdinand Avenarius, edited Der Kunstwart. This mass-circulation journal shared Pazaurek’s aim of alerting the German middle-class to the dangers of bad taste while cultivating wider understanding of the merits of good design and high-quality industrial manufacturing. Following Pazaurek’s lead, Der Kunstwart established an archive of “abominations” in home furnishings and a traveling photographic exhibition on the same topic.