Free-for-All

A. S. Neill and Summerhill

Christopher Turner

I first visited Summerhill, the “free” school founded by A. S. Neill in 1921, when I was an anthropology student. I asked whether I could stay for a while as a participant-observer and was offered a large tepee as my temporary residence. I liked the idea of living in it, a tepee being a suitably ironic home for a backyard anthropologist. However, everything at Summerhill—where lessons are voluntary and the pupils invent their own laws—is put to a public vote, and the children decided they wanted to keep the tepee for themselves.

So for the entire summer of 1993 I lived in bed-and-breakfast accommodation in Leiston, a market town in Suffolk, England. All the other guests worked for Sizewell B, Leiston’s only other attraction; every piece of crockery and all the towels and cutlery were stamped with the nuclear power station’s logo, unwanted gifts offered to people who worked there. The owner of the bed and breakfast had been given a free sweater after a random Geiger counter inspection had determined that his own, hung out on the clothesline, harbored dangerously elevated levels of radiation.

Summerhill occupies a large, austere Victorian building on the outskirts of the small town; at the time, its worn grounds were dotted with portacabins, which served as makeshift classrooms, and shabby, overgrown caravans in which some of the teachers lived. The place had a curiously temporary feel, with the character of a friendly squat or a traveler encampment rather than a boarding school. About seventy pupils, aged five to eighteen, lived there; their parents paid nine thousand pounds a year for the privilege. Just before I arrived, a notorious documentary had portrayed the students behaving with Lord of the Flies–like abandon; in the film, two pupils were married in a mock ceremony and a group was shown hunting down a rabbit and beheading it with a machete.

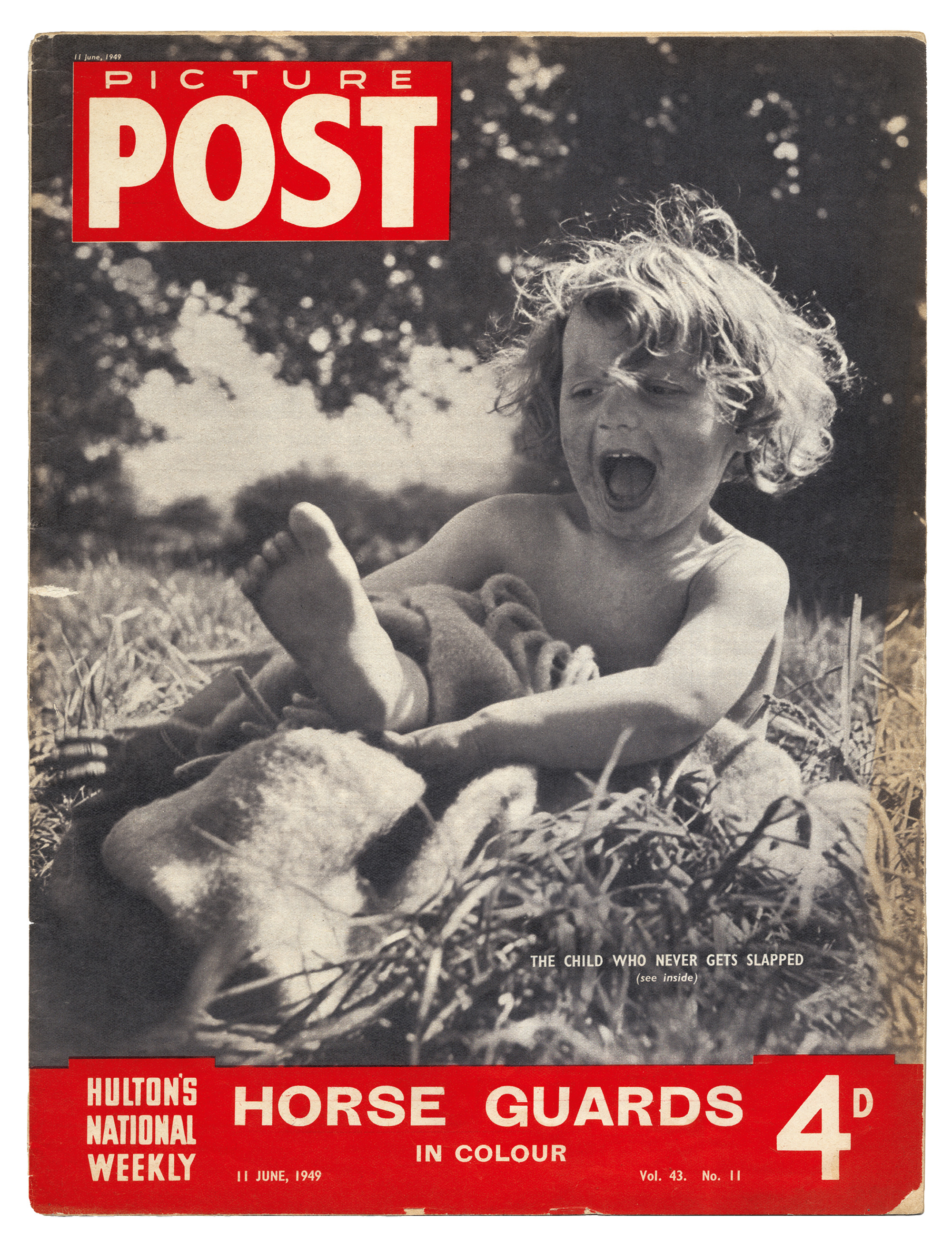

Neill, a curmudgeonly and idealistic Scot, believed that Summerhill offered children a sanctuary from the moral contamination of the world. “We set out to make a school in which we should allow children freedom to be themselves,” Neill wrote. “In order to do this we had to renounce all discipline, all direction, all suggestion, all moral training, all religious instruction.” In twenty books crammed with big-hearted anecdotes he propagated his pedagogical philosophy: “Summerhill is possibly the happiest school in the world,” he claimed. “Hate breeds hate, and love breeds love.” He had a Rousseau-like faith in the intrinsic goodness of the child. The school’s motto continues to be: “Giving children back their childhood.”