The 1994 Northridge earthquake cracked the façade of Robert Stacy-Judd’s Masonic Temple (built in 1951) in the San Fernando Valley in California. The structural damage that the Mayan Revival–style building suffered was so severe that the temple was deemed unsafe and the lodge was closed. For a time then, the building was an authentic Neo-Mayan ruin.[1] The spectacle of these Mayan Revival ruins, not those of the ancient Yucatecan Maya, brings to mind the nineteenth-century engravings used to illustrate travel writings, such as Frederick Catherwood’s celebrated images for John Lloyd Stephens’s Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan (1841) and Incidents of Travel in Yucatan (1843), which had originally inspired Stacy-Judd. Like Catherwood’s engravings, the North Hollywood Masonic Lodge, and other structures in this particular revival style, attempt to stake a claim to the distant Mayan past. By doing so, they aim to naturalize a specific relationship between the present and the past, an ideologically charged turf-staking to which architecture and archaeology both lend themselves particularly well. Given the broad history of the uses of Mesoamerican antiquities and references to legitimize governments, to evoke worlds of ancient mysticism, and to forge hemispheric bonds, Stacy-Judd stands out as a particularly idiosyncratic figure. The multiple contradictions of Stacy-Judd’s life and roles—an Englishman in search of an “All-American” architectural style, and an importer of Mayan styles to the Yucatán, their place of origin—all point to the complexities of a life which reveals much about Pan-Americanism, appropriation, and the diverse contemporary uses of architectural styles lifted from Ancient America.[2]

Robert Stacy-Judd (1884–1975) came to learn of Mayan architecture through Catherwood’s etchings. Having made this discovery, he abandoned his youthful flirtations with other “exotic” architectural styles: ancient Egypt (Electric Picture Palace, Isle of Wight, 1910–1912; Beni-Hasan Theater, Store, and Office Building, Arcadia, CA, 1923–1924), Tudor England (Elks Home, Williston, North Dakota, 1914–1915), and the Islamic Middle East (in his designs for a 1916 auto show in North Dakota).[3] The ancient Maya, as evoked by his Aztec Hotel, were not a phase for Stacy-Judd, but a lifelong fascination. He filtered his perceptions of the ancient Maya through esoteric ideas about the spiritual power of the ruins. Unlike other more formalist and modernist appropriations of the pre-Columbian past, such as those by Frank Lloyd Wright, Stacy-Judd’s buildings reveal a sensibility that is more theatrical than architectural. Stacy-Judd saw in the Maya the mawkish story of a lost Eden, enlivened by royalty and pomp, which he dramatized in colorful costumes, flamboyant architecture, romantic poetry, and speculative literature. His greatest triumph was the Aztec Hotel (Monrovia, CA, 1924–1925), which achieved overwhelming popular success, and earned praise in publications ranging from the New York Times to the trade magazines American Architect and the Hotel Monthly. It was the Aztec Hotel that launched Stacy-Judd’s career as a promoter, explorer, and chronicler of the ancient Maya.

Stacy-Judd did not confine his professional activities to architecture. He published poetry and speculative rants, filmed a travelogue, lectured, and recorded radio broadcasts on archeological topics. He even designed and patented the “Hul-Che Atlatl Throwing Stick,” which he claimed was derived from ancient Mayan prototypes. As an archeologist, Stacy-Judd’s contributions are negligible. At a time when the wild armchair speculations of Victorian anthropology were fast becoming outmoded, he brought to the table a poorly synthesized stew of ideas borrowed from Ignatius Donnelly, James Churchward, and Alice and Augustus Le Plongeon. But Stacy-Judd’s peculiar genius lay in his flare for showmanship, not in his scholarship. He found his place in Southern California, hobnobbing and frolicking with the Hollywood crowd. Bette Davis turned to him to satiate her curiosity about the Maya. He even proposed a feature-length fiction film set at Chichén Itzá called The Scarlet Empress for which he labored in his later years on costumes and sets. Without the opportunity to produce this technicolor melodrama, without commissions for anything other than prosaic San Fernando Valley ranch houses, in the 1940s and 1950s Stacy-Judd’s imagination ran wild at the drafting board. He conjured up a number of fantastic, never-completed projects, such as the proto-Epcot Center village of Native American reinterpretations called the “Enchanted Boundary.” None of his later projects ever garnered the high praise which the Aztec Hotel won for him. How was it that this Monrovia hotel captured the imagination of so many? The 1925 Aztec Hotel embodies the enormous vogue for things Mexican, and represents a turning point in the history of the Mayan Revival Style in the United States, distinct from both the more imperial era which it followed and the “Good Neighbor” phase, which coincided with World War II.

Earlier efforts to revive Ancient Mayan building styles in the United States coincided with and embodied the spirit of a period of hemispheric expansion. Following the territorial enlargement resulting from the US-Mexican and Spanish-American Wars, North Americans flocked to exhibitions where they could see something of these recent, distant acquisitions. These included displays of human specimens, antiquities, and plaster casts of archeological curiosities. P. T. Barnum was apparently responsible for a hoax which toured the US and Europe, a pair of microcephalics billed as “descendants and specimens of the sacerdotal cast (now nearly extinct) of the Ancient Aztec founders of the ruined temples of that country, described by John L. Stephens Esq., and other travelers.”[4] Barnum was not the only one hoping to capitalize on the success of Incidents. In late nineteenth-century New York, the Globe Museum, the Orrin Brothers, and the Nichols Aztec Fair all exhibited “the last descendants” of this ancient race.[5] This designation predicted the imminent demise of the Indian, recasting colonialism as preordained fate. The framing rhetoric positioned pre-Cortesian America as a heritage without living heirs and available to be claimed. In the 1893 Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, Edward Thompson’s archeological casts included a life-sized copy of the arch at Labna. Standing guard by the arch was Desire Charnay’s cast of a Mayan Indian, frozen in time like a fossilized human being. These displays embody the climate of westward expansion and Manifest Destiny that shaped early American anthropology. Thompson, who bought the ruins of Chichén-Itzá and smuggled gold and jade from its cenote (sacred well), and Augustus Le Plongeon, who harnessed a dozen of his Mayan laborers to the stone Chac Mol in an aborted attempt to drag the object to Philadelphia, exemplify this acquisitive age. The removal of archeological loot went hand in hand with the search for raw materials, new markets, and land. The 1823 Monroe Doctrine set the tenor for an American foreign policy premised on the belief that the hemisphere belonged to the US. The replicas of Mayan ruins that constitute the origins of the revival style served as part of the symbolic turf-staking which buttressed this imperialist notion.[6]

In contrast, by the late 1930s, the building of Mayan Revival structures in the US had gained an altogether different political urgency. The repeated US invasions of Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico in the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had made Latin America suspicious and hostile to the colossus to the North. Wary of this ill-will, the Good Neighbor Policy of the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations championed policies of mutual respect, cooperation, and non-intervention. The growing threat of fascism in Europe heightened the need for hemispheric unity. Unlike the earlier unilateral appropriations, the exhibitions and recreations of ancient Mesoamerica in the US in the 1930s and 1940s were typically collaborative efforts in which both the US and Mexican governments participated.[7] Of this era, art historian Holly Barnet-Sanchez writes that “the United States government was not only seeking a rapprochement with all of Latin America but was also pursuing this policy within a clearly defined language of shared histories and cultures. Thus, by 1933 ‘the Other’ had in effect become one of ‘us.’”[8]

Architecture offered an ideal vehicle for this diplomatic move. Following the direction anticipated by the “Aztec Garden” of the Pan-American Union building (Albert Kelsey and Paul P. Cret, Washington, DC, 1910), Mayan Revival architecture made public declarations of a common American heritage. San Diego’s former Federal Building (Richard Requa, 1935), a bit of Uxmal in Balboa Park, and Mérida’s Parque de las Americas (Manuel Amábilis, 1946) where stelae naming the states of the Americas proclaim the shared Mayan ancestry of nations including Canada, Uruguay, and Cuba, all embody this phenomenon. Neither diplomatic offering nor colonial proclamation of ownership, the Aztec Hotel represents a transitional moment in US Neo-Mayanism, poised between the expansionism of the previous century and the diplomatic necessities of the Good Neighbor era.

Like P. T. Barnum’s failure to distinguish between the Aztecs of Central Mexico and the Mayan ruins described in Stephens’s account, the appellation “Aztec” for a building which is based on the peninsular “Mayan” style represents a conflation of two very distinct regions and cultures of Mexico. The hotel’s designation was not so much a misnomer as a concession to a North American public that may not have read Stephens’s 1841 account. The ruins of Maya in Central America, Yucatán, and Chiapas were less well known to the North American public than those of the Aztecs of the Central Valley.[9] However, that was changing. The 1920s represents a high watermark for the North American fascination with Mexican culture.[10] That was the decade when modernist dancer Ted Shawn toured middle America with Francisco Cornejo’s costumes and Martha Graham’s performance in Xochil, a pre-Cortesian dance. Battery company executive and amateur Mayanist Theodore A. Willard published his mannered archeological fiction, Bride of the Rain God: Princess of Chichén Itzá and The City of the Sacred Well. Stacy-Judd’s tour-de-force coincides with the inauguration of the Carnegie Institution’s Chichén-Itzá excavations (1923–1933), popularized in periodicals like National Geographic.[11] Ann Axtel and Earl Morris published popular autobiographical accounts of their work with the Carnegie project. In 1923 the Yucatecan governor Felipe Carrillo Puerto opened a road connecting Chichén to the outside world. As we shall see, Carrillo Puerto’s motives for championing this Revolutionary Mayan revival differed from those of the Carnegie, but in practice their agendas coincided. But of all these Jazz Age visions of the ancient Maya, none was more delirious than that of Stacy-Judd. His Aztec Hotel opened to a United States primed for pre-Columbian spectacle.

The hype that developed around the Aztec Hotel (a good deal of which was instigated by Stacy-Judd himself) celebrated it as “the only building in the United States that is 100% American.”[12] Turning to autochthonous sources was a frequent strategy for North Americans in search of an authentic, non-European identity. Often this search called for face paints, secret rituals, and the taking of indigenous appellations. Posing in profile, as in a Mayan bas-relief, Robert Stacy-Judd displays for the camera his Mayan headdress and robes. By dressing himself as a Mayan lord, the English expatriate engaged in a venerable American tradition of “playing Indian” that dates back to colonial times, if not earlier. Blackface and redface were old American strategies that served diverse functions.[13] Sometimes a disguise for rebellions that protested misrule, often a part of celebrations and ceremonies, and always an assertion of whiteness, this practice predates the Boston Tea Party.[14] Much like the rebellious Boston colonials, Stacy-Judd donned his Indian robes to cut the umbilical cord to Europe. He joined members of the Improved Order of the Redmen, the New Confederacy of the Iroquois, and the Boy Scouts’ “Order of the Arrow” in a 100 percent American search for authenticity and rootedness through an aboriginal disguise.

Stacy-Judd’s cross-cultural transvestism was much more than a single evening’s act of symbolic rebellion. Building private houses and public buildings throughout the United States in the Neo-Mayan style, Stacy-Judd always took his appropriation of the indigenous a step further. Stacy-Judd’s was a double appropriation of alterity, paraphrasing, in a single structure, the Mexican and the Native American. Paradoxically, subsequent to the genocide, Native Americans became arguably that group whose names, likenesses, aesthetics, foods, dances, bodies, etc. were appropriated more often than any other ethnic group in the Americas. Within architecture, however, the appropriation of Native American forms was unusual in 1924, though precedents had been set by movie theaters (the Aztec Theater, Eagle Pass, Texas, 1915), at World’s Fairs (the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the 1915 Panama California International Exposition in San Diego) and by a few private homes.[15] By evoking autochthonous America, the Aztec Hotel anticipated the later Pueblo Deco style popular in the 1930s. Stacy-Judd’s own Soboba Hot Springs Hotel and Indian Village (San Jacinto, 1924–1927), with its Pima and Yuma cottages, a cocktail of Pueblo, Maricopa, and Hopi styles, probably represents the apogee of this short-lived architectural trend.[16] Appropriations of colonial Mexican architectural styles were more common. At the time Stacy-Judd designed the Aztec Hotel, the Mission Revival was at its apex in Southern California. Later he produced buildings like the Neil Monroe House (Sherwood Forest, CA, 1929), with eclectic blends of Mission and Mayan elements. While Stacy-Judd’s Aztec Hotel was not the first architectural appropriation of Ancient Mexico, the reference was unusual enough for him to make that claim.

Stacy-Judd’s Aztec Hotel was built in the context of a generalized taste for architectural exoticism that flourished in Southern California in the 1920s. It is linked not only to the Mission Revival in its regionalist evocation of an exalted history, but also to the other whimsical references to the exotic in the region, such as Mann’s Chinese Theater (Hollywood, 1927) or the Samson Tire Works (1929, today the Citadel outlet mall). Often, the dialogue with the emerging cinema industry is pronounced, either in the building’s function as movie palace or in references to distant locales, like the Babylonia of D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) or the Mexico-Tenochtitlan of Cecil B. De Mille’s The Woman Who God Forgot (1917). Related too is the rise of the whimsical roadside vernacular architecture that Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour named “duck,” in recognition of a Long Island diner shaped like (and specializing in roast) duck.[17] Contemporaneous Southern California structures such as the Brown Derby (1926), the Tamale (1928), and Tijuana’s Sombrero (1928) share a playful sense of building as symbol. Yet in spite of the relationships between the Aztec Hotel and these other examples of quirky, exoticized, and movie-set architecture, Stacy-Judd found in the Maya more than simply a revival style. The deeper resonances of the image of Stacy-Judd in Mayan costume evoke the ritual life of those millions of middle-class American males involved in secret societies and fraternal organizations.

Especially in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Freemasons, the Knights of Pythias, the Odd Fellows, and hundreds of smaller groups offered ritual, conviviality, fellowship, and entertainment to citizens in a society where social roles were in flux.[18] Members of these groups might impersonate Druids, Romans, or Native Americans in elaborate secret rites. One such group was the Mayan Temple and Alliance of American Aborigines of Brooklyn, New York, founded by Harold Davis Emerson, PhD, DD, in 1928.[19] This temple, “similar to Masonry,”[20] offered ritual, dance, and classes on hieroglyphic writing to its members. Here was a natural constituency for the Mayan Revival style. Though the Mayan Temple never had sufficient resources to commission their own building, they describe their quarters:

The Mayan Temple has now been completely redecorated. Through the courtesy of Chief Lynx and Brother Richard Bolanz, picture-writing and beautiful murals adorn the walls and ceilings. On the frieze in Indian picture-writing is the story of the Mayan Temple. Above it on the ceiling is the Mayan seal and the various clan totems. … On the west wall is a reproduction of a Mayan ruined city buried in the jungle.[21]

Their newsletter provides an overview of the concerns of the Brooklyn Maya. News briefs report on the Carnegie Institution excavations and the evidence of ancient Mayan use of the telegraph. Mayan astrology is employed to predict the future of Roosevelt’s New Deal initiatives. Frequently, articles dispel negative perceptions of the Indian as savage, backward, prone to practice human sacrifice, or violent. Credited or not, much of their account of the Maya is derived from the Le Plongeons.

For Masons and related groups, architecture was a subject of paramount importance. The Masonic quest for architectural perfection, embodied by the lost design of the Temple of Solomon, probably originates in their roots as Medieval British stone hewers. This interest often led the Mason to paraphrase the ancient Egyptian monuments, sometimes on an ambitious scale.[22] But followers of Augustus Le Plongeon, who argued the Egyptian mysteries originated with the peninsular Maya, turned to Native American architecture. Not surprisingly then, many of the major patrons of Mayan Revival buildings are Masonic Lodges, theosophical groups, and other occult confederations. Robert Stacy-Judd found a like-minded patron in the founder of the Philosophical Research Society, Manly Palmer Hall. Here the Mayan Revival style embodied not Manifest Destiny, but a supernatural destiny made manifest.

Southern California is only one of the places where Stacy-Judd sought to promote his Mayan Revival. The Stacy-Judd archive includes proposed projects in Mexico City, Iztapalapa, and Guatemala City. If the Mayan Revival in Monrovia evoked the exoticism of distant pyramids, in Mexico the style took on completely different meanings. Encouraged by the success of the Aztec Hotel, Stacy-Judd set off to Yucatán to see the original models and to promote his designs. In Mérida he was invited to the office of the state governor, as he describes the visit in his travelogue:

My reason for visiting the Yucatan, primarily, was to further my efforts in creating an all-American architecture and its allied arts. … For one whole hour the interview lasted. All things considered, the situation was extraordinary. I had been given to understand the Yucatecan to be indifferent to the potential wealth of his country, namely, the Mayan ruins. I was amazed to learn that, quite the contrary, he is vitally interested.

After I had finally answered numerous inquiries regarding my adventures in Yucatan up to that time, the Governor asked to see my watercolor studies of Mayan adaptations. And when we finally parted, he said in his cordial manner, “Don’t forget, Señor, our country is yours.”

… Glancing back as I left the “Building of the People,” my eye caught sight of an oil painting standing on an easel in the open foyer. It was an oil painting of the late General Carrillo, Governor of Yucatan. He it was who commenced this structure, intending it to be his residence—but alas! he was murdered in 1924, while in office.[23]

Stacy-Judd’s assumption that the modern Yucatecans were “indifferent” to the ruins echoes the writings of other European and North American travelers, including Stephens’s own Incidents. These accounts consistently attempted to separate the ancient Maya and their spectacular cities from their contemporary descendants. Stephens had lamented “that so beautiful a country should be in such miserable hands.” Though he rejected the wilder diffusionist theories that circulated widely at the time, he nonetheless believed that “no remnant of this race [of architects] hangs round the ruins.”[24] Stacy-Judd learned that this indifference was a self-serving misperception, propagated by writers like Stephens.[25] Upon his arrival in Mérida, Stacy-Judd discovered that the contemporary Yucatecans were so “vitally interested” in their past that they had arrived at their own very different Mayan Revival style independently of him. The “Building of the People” (La Casa del Pueblo), where the described appointment took place, is in the Mayan Revival style. Though the building, designed by the Mexican architect Angel Balchini, was completed in 1928, the fact that Stacy-Judd mentions that the project was initiated by Carrillo Puerto (governor 1923–1924) suggests he was aware that the building was almost exactly contemporary with his Aztec Hotel.[26] Stacy-Judd’s strange silence here not only protects his claims as the first to revive the architecture of the ancient Maya, but also elides his own position as an importer of Mayan architecture to its place of origin.

The Yucatecan version of the Mayan Revival arguably predated the Mexican Revolution, but it was under the auspices of the Revolution that it flourished.[27] As such, it was part of a larger political and social program, one which consciously used culture as a means to elevate the subaltern.[28] In the Yucatán, the Revolution came not as an organic uprising from below, but as an imported phenomenon.[29] The principal leaders, Salvador Alvarado and Felipe Carrillo Puerto, were in some ways like caudillos [strongmen], a Leninist vanguard intent on jump-starting a radical social movement among the indigenous majority still emerging from an oppressive system of debt-peonage bordering on slavery. Monuments and public buildings were an important part of their program to stir pride in the glorious Mayan past. In spite of the massive immigration of Mexicans to Southern California in the 1920s, accelerated by the push of Mexican domestic upheavals and the pull of labor shortages in the US, the Aztec Hotel only addresses an Anglo public. If Stacy-Judd’s use of ancient Mayan motifs in Monrovia and elsewhere in Southern California are examples of a cultural appropriation of a geographically and historically distant Eden, in Mérida his project takes on an entirely different character, that of a repatriation, albeit one highly transformed. During his stay in the Yucatán, Stacy-Judd came to know the Revolutionary socialist state’s version of the Mayan Revival. He was overwhelmed:

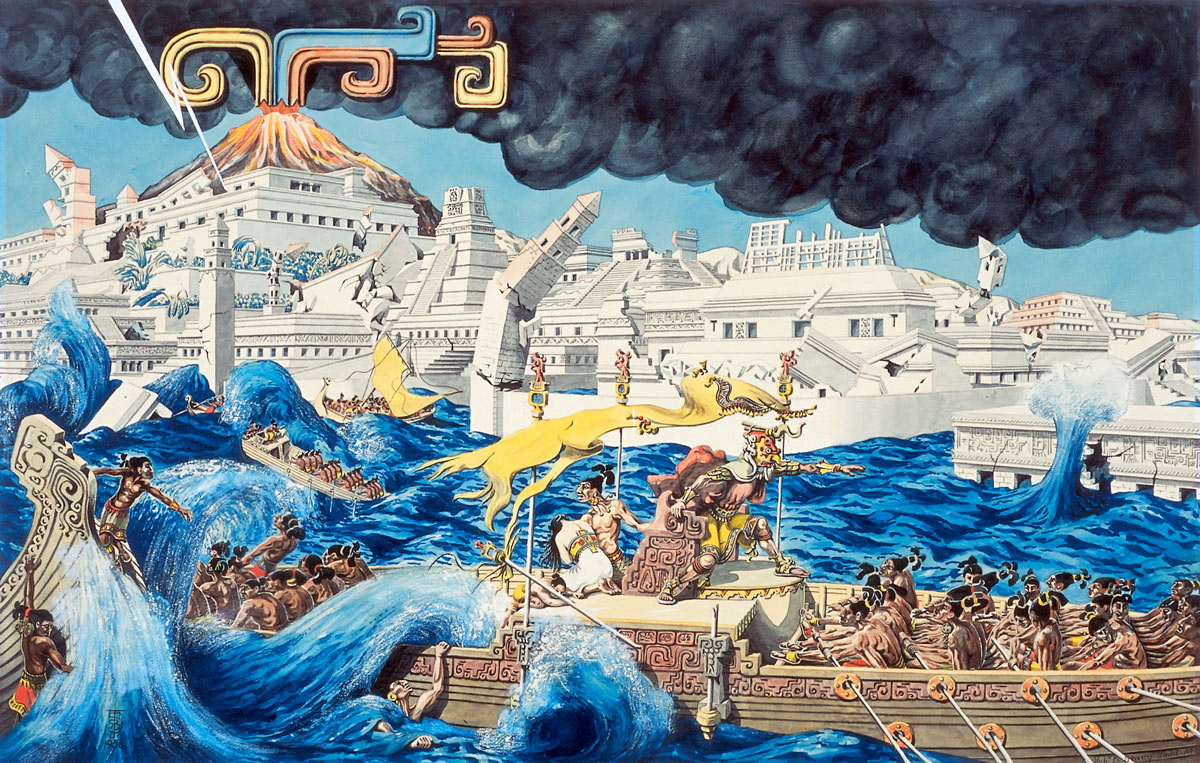

There is plenty of evidence that the Yucatecan is awakening to an appreciation of the civilization whose extraordinary works lie buried in the jungle-growth fastness of his country. As one instance, the latest opera of Señor Luis Rosado Vega, Yucatan’s favorite composer, was Mayan, and the night of its premiere production in Mérida was of red-letter importance. …

The story told of the Nahuatl introduction among the Mayas of human sacrifice, and centered around the custom of presenting a beautiful virgin as bride to Yum Chac, the Rain God, in times of extreme drought, the scene of action was, of course, the now famous Sacred Well at Chichen-Itza. …

The costume designs were accurate as to classical style and presented a gorgeous appearance. They were by far the outstanding features of the performance and more clearly exemplified the true ancient Maya than did either the music of the settings. No New York stage fantasy ever surpassed in costuming the beauty and striking colorfulness expressed in these cleverly conceived and artistic creations.[30]

Unlike those North American visitors who came as leftist pilgrims, Stacy-Judd took no notice of the radical social experiment underway.[31] What drew him was the costume drama of the Mayan opera. Today the visitor to the Aztec Hotel cannot help but notice its state of disrepair. Richard Requa’s Federal Building in San Diego (1935) has been converted into the Sports Hall of Fame, but the decorative Mayan trim is crumbling off the sides. While many of the ruins that inspired these structures have been restored and found a second life as tourist attractions, the Mayan Revival buildings have all too often fallen toward ruin.[32] In an age of NAFTA and the militarized border, the ambitions of westward and southward national expansion and the ideals of Pan-American unity that inspired these buildings are anachronistic. Fifty years after New York “stole the idea of modern art,”[33] when globalization is often taken to mean Americanization, the search for an “authentic American style” or for an architecture which is “100 percent American” seems a dated preoccupation. Today’s Mayan Revival buildings are more likely to be amusement park attractions, located in places as distant as Catalonia or the Bahamas, than monuments to inter-American understanding and cooperation. Yet in spite of the perceived irrelevance or datedness of the ideas that spurred on this revival style, the work of Stacy-Judd anticipates the postmodern turn in architecture. His collision of distinct styles and geographically distant citations in unrealized projects like The Streets of All Nations (1938), with its Russian, Hindu, French, and (inevitably) pre-Columbian units, remind contemporary viewers of theme park architecture. The jumble of the Philosophical Research Society’s quotations anticipates Frank Gehry’s Aerospace Museum (Los Angeles, 1984). Distant from the pared down modernist primitivism of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum, Stacy-Judd’s is an alternate path that looks to both the past and the future.

Jesse Lerner lives in Los Angeles, where he writes, teaches, and makes documentary films. He is an editor-at-large at Cabinet.