Colors / Gold

Pop’s magic suit

Michael Bracewell

“Colors” is a column in which a writer responds to a specific color assigned by the editors of Cabinet.

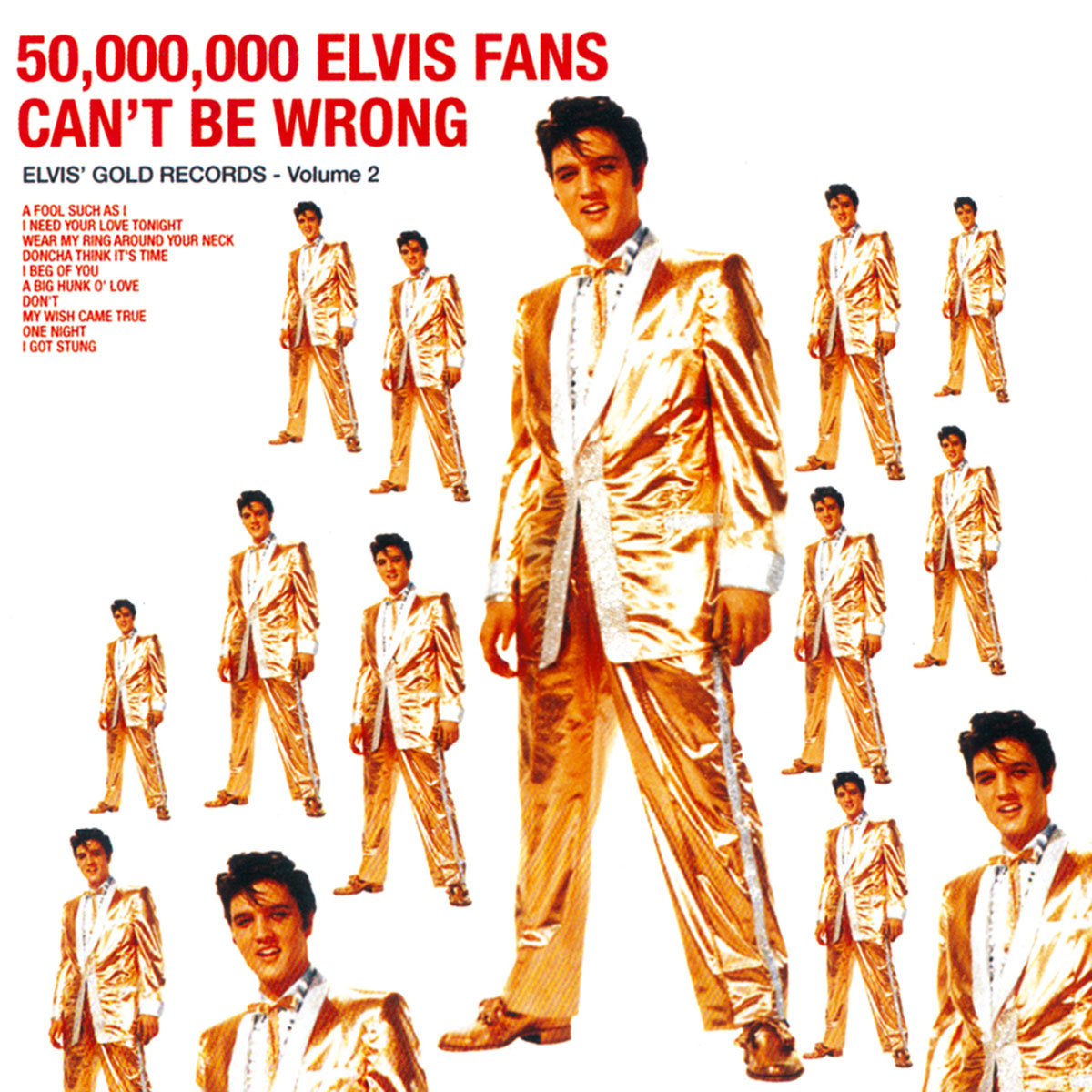

Elvis stands with his feet spaced widely apart, his shoulders dropped, his arms hanging loosely. There is good-humored self-consciousness in the young King’s demeanor, but what renders him regal, by way of the most immediate signifier on offer, is his suit (and bow-tie) of pure shining gold. By common assent, Elvis’s reign is undisputed, and the gold suit—it looks as shiny as kitchen foil—is the garment that transforms him from commoner to monarch. The effect is more vaudevillian, almost clown-like, than rock-and-roll cool, but such is the iconic image on the cover of Presley’s 50,000,000 Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong, released in 1959—just three years after his breakthrough single “Heartbreak Hotel” dominated the charts on both sides of the Atlantic—and in doing so arguably marked the beginning of the pop age as we know it.

Elvis’s gold suit, for all its swagger, somehow lacks sex appeal. Glancing quickly, you might think that the King was wearing a rather extravagant pair of pajamas. It is a garment clearly descended from the ceremonial dinner suits worn by dance band musicians and theatrical entertainers—although Elvis’s pride in being an “entertainer” would remain one of his most endearing qualities. (Later, when fat, imperial, and high on kung fu, Elvis would be asked at a press conference what he thought about US involvement in Vietnam. “Ah’m sorry suh,” he mumbled back, “but ah’m jus’ an entertainer.”) Back in 1959, however, the totality of the suit’s gold, its sheer slab-like shimmer—more TV game show than Versailles—asserted a pop Americana update of Shakespeare’s oft-quoted comment on style and kingship: “My presence, like a robe pontifical, ne’er seen but wonder’d at.”

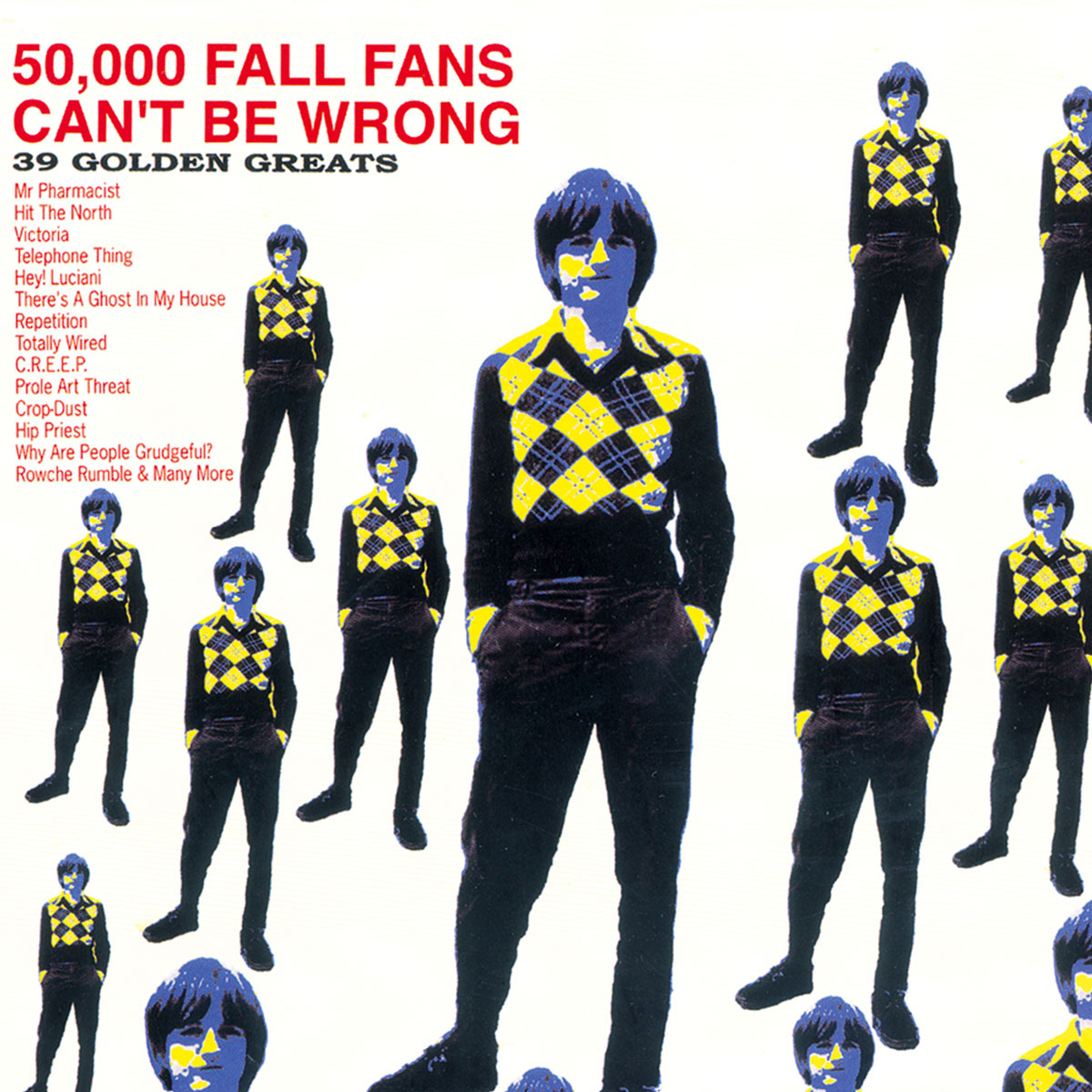

For 50,000,000 Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong, Presley was suited in gold by the wonderfully named Nudie Cohn—whose own story, as the King’s tailor, reads like a glamorously American reclamation of a European fairy tale. Nudie had arrived in New York in the 1940s, and started a business making “undergarments for showgirls”—an occupation which one somehow imagines being Groucho Marx’s dream job. “Nudies for the Ladies” was a fair success, but it was only later, after a country singer called Tex Williams bought Nudie a sewing machine from the proceeds of an auctioned horse, that “Nudies Rodeo Tailors” was born in North Hollywood to provide rhinestones and fringes to the aristocracy of American music. (Some forty-five years after Cohn created Elvis’s look for his 1959 album, Mark E. Smith—ever pop’s republican—would be found on the cover of 50,000 Fall Fans Can’t Be Wrong with the kingly gold suit replaced by sweater and jeans.)

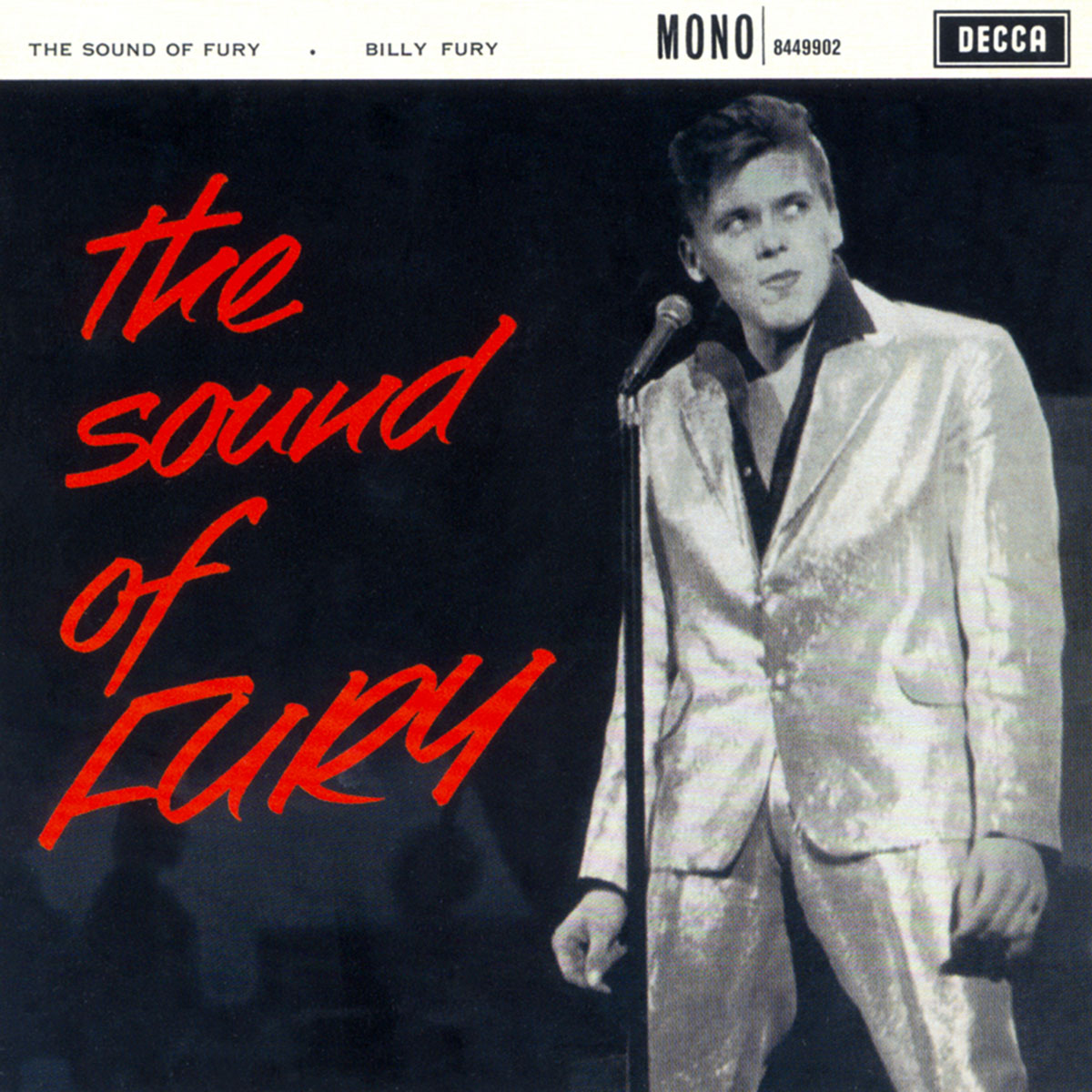

In terms of myth, Nudie Cohn’s gold suit for Elvis can be seen as the beginning of a lineage—the creation of a mantle to pass down, and the inauguration of gold as an archetypal aspect of pop iconography. Fast-forward a year and cross the Atlantic to Liverpool, where Billy Fury—“The Elvis of Birkenhead”—has just recorded his signature album, The Sound of Fury. Released in 1960 on the Decca label (they who would turn down the Beatles) and destined (unfairly) to reach only number eighteen on the UK Top Twenty, The Sound of Fury remains distinguished as a great British Beat album mostly by way of its cover artwork. Now it’s Fury wearing a (or “the”) gold suit—this time with a black shirt—and somehow he looks cooler and sharper than the King himself. It is as though the gold suit has lost the stiffness of its newness, becoming worn-in and slick. It has also become strangely Anglicized—less brash and loud—even though the entire universe it celebrates is primarily black American.

Combine the stage name Billy Fury with the ceremonial pop mantle of the gold suit and you have a virtually pure pop statement—up there with Johnny’s leather jacket in The Wild Ones or Johnny Ray’s hearing-aid or Lord Byron’s club foot. Gold—oft reputed, like diamonds, to curse those who crave it—is both an alchemical substance (that which has been refined, leaving behind the dross) and capable of conducting a current, a useful capacity in a medium which, to quote Patti Smith, is the (un)natural consequence of “Art + Electricity.” But might pop’s gold suit be haunted—fable-like, bestowing fame, wealth, and glamour in exchange for long life, and even soul? (British artist Linder’s recent performance work and film, The Dark Town Cake Walk: Celebrated from the House of FAME (2010), enacts this exchange, delivering on cue the archetype of the Star—clad in gold lamé—who is placed in sacrificial configuration with the archetype of the Witch; Linder’s point being the relationship between glamour and magic.)

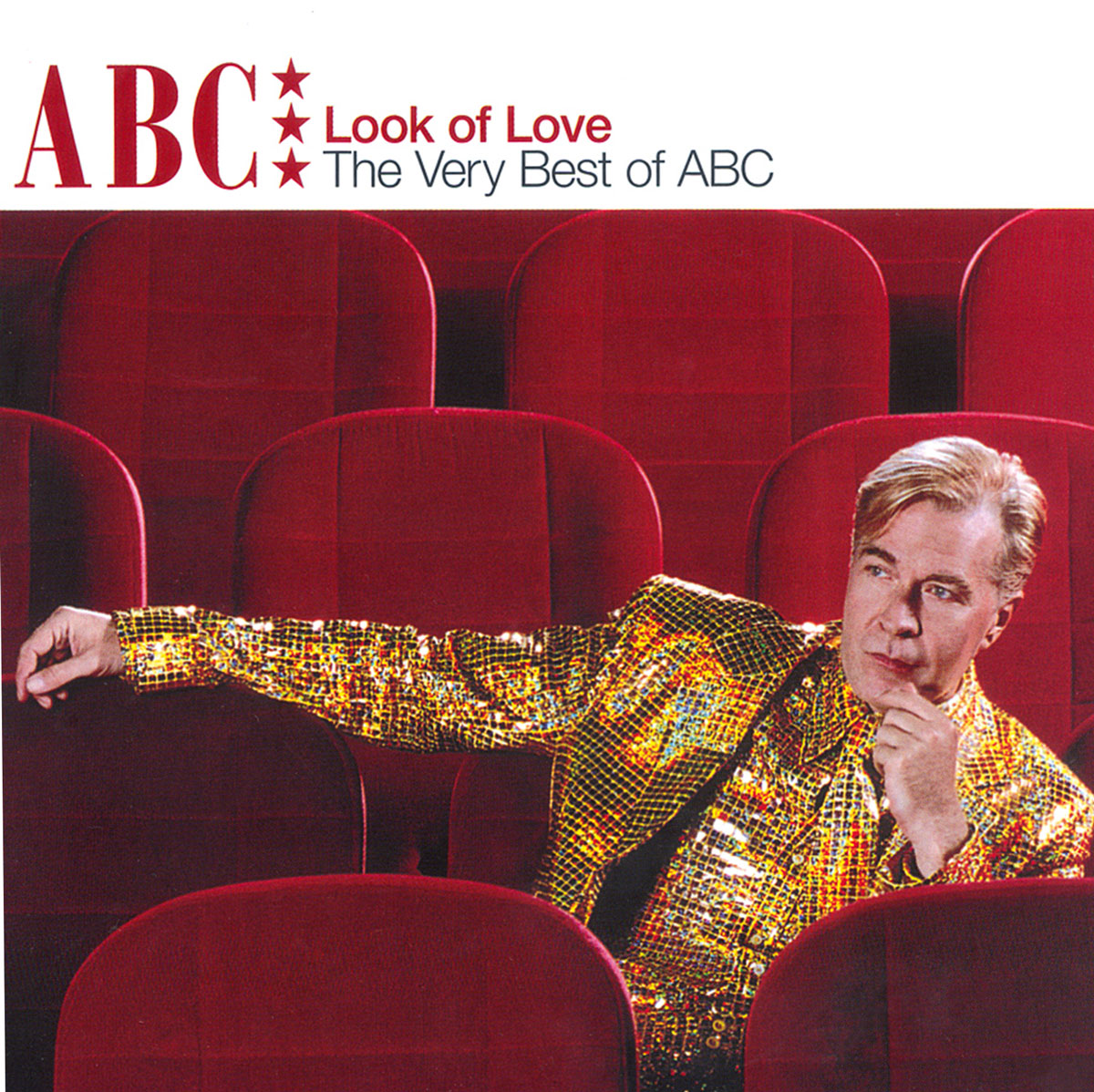

And so: Elvis dead of heart failure by 1977; likewise, tragically, Billy Fury by 1983—the year New Romanticism morphed into the soundtrack of Yuppie dreams of la vie deluxe by way of Spandau Ballet’s UK number two hit, “Gold,” with its exhortation to “always believe in your soul.” (Meanwhile, if you go to Liverpool’s great Anglican cathedral, pop fans, you’ll discover in the choir there a simple oak lectern with the name “BILLY FURY” inscribed in gold—a conflation of faiths that is hard to resist, remake, or remodel.) With his usual acuity, British style analyst Peter York would subsequently note the manner in which the trajectory of New Romanticism would keep in perfect step with the rise of Thatcherite ideology—“Gold,” in all its triumphalism, was the perfect song for the new generation of venture capitalists with smooth jaws, clean arteries, and fat pens.

But the gold suit—untamed—dances down the decades. In 1973, for example, we find the young Malcolm McDowell starring in O Lucky Man!, Lindsay Anderson’s relentlessly cynical update of A Pilgrim’s Progress. The suit is fitted for him by a fellow resident in a seedy hotel, who appears to be as much an agent of destiny or emissary of fate as the Hotel Manager in Benjamin Britten’s operatic version of Death in Venice. McDowell wears the suit as though it were Arthurian armor—or as though it shared, with profound irony, a mid-Victorian, Anglo-Christian interpretation of Arthurian virtues. But still it cannot protect him. We see him plunging through Arcadian English countryside, soon to blunder into a horrific “research facility.”

The magical aspect of glamour is unsurprisingly volatile, and pop’s gold suit, even as it appears to empower and enshrine, also seems to bring with it the sin of hubris (“insolent pride towards the gods,”) that seldom goes unpunished by the vagaries of mortality. Marc Bolan, Malcolm McLaren, and Morrissey will all triumph on pop’s stage in shining gold—yet each has (or had) more than a nodding acquaintance with the shadow. In this, we might look upon pop’s golden raiment as articulating, with a precision that is almost too neat, the dynamics of classic myth: ambition, triumph, irony, and tragedy. So always believe in your soul.

Michael Bracewell is a writer based in London. Recent books include new editions of his novel The Conclave (Secker & Warburg, 1991/Capuchin Classics, 2010) and England Is Mine (Flamingo, 1997/Faber Finds, 2010).