Inventory / Blind Sight

The secret signs of the cataract surgeon

Christopher Turner

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

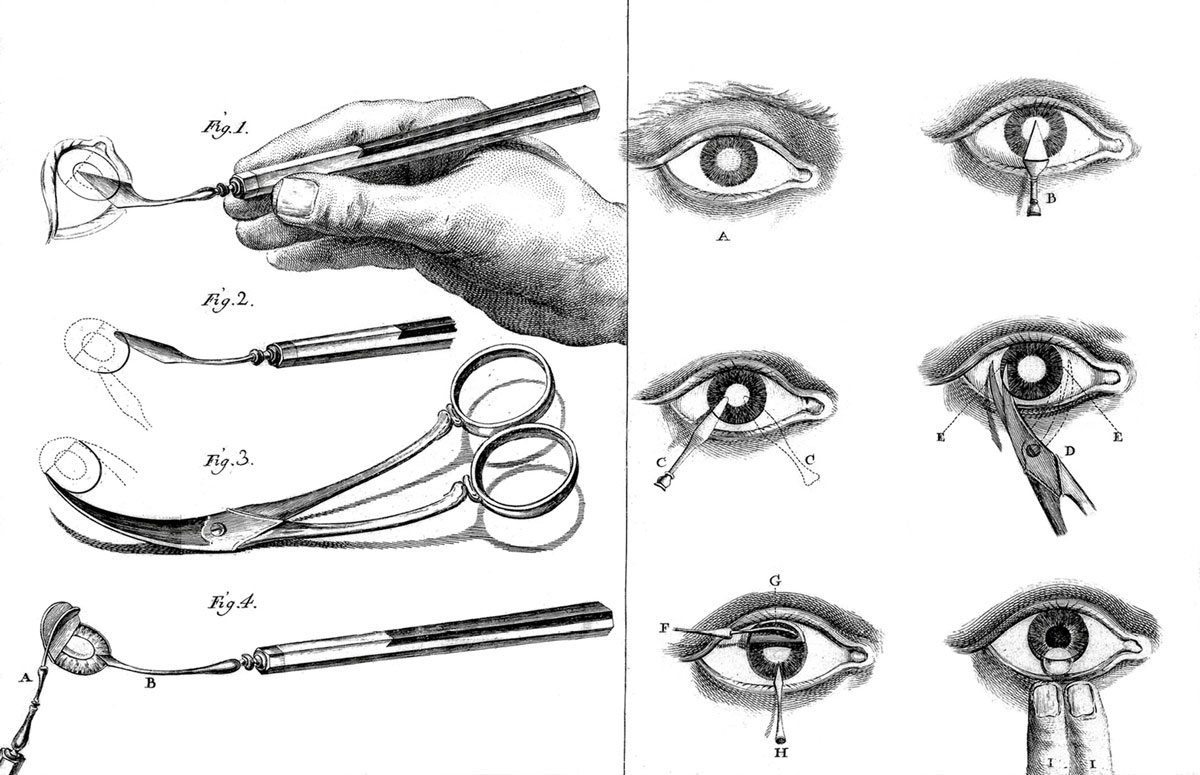

On 8 April 1747, Monsieur Garion, a blind wigmaker, sat on a stool in nervous anticipation. A man standing behind him held his head steady, one hand firmly under Garion’s chin, the other peeling back the upper lid of his eye. Surgeon Jacques Daviel sat in front of them on a slightly higher chair and held down Garion’s lower lid. Steadying his elbow on his knee, Daviel brought a sharp triangular-shaped knife up to the wigmaker’s clouded eye and, without anaesthetic, pierced the cornea. Using another curved cutting knife and convex scissors, this wound was opened to create and lift a half-moon-shaped flap. A sharp needle was applied directly to the lens; any adhesions between it and the iris were severed with a blunt spatula. As fluid flowed out of the eye, gentle pressure was applied to the lower lid to help dislodge and remove the patient’s cataract.

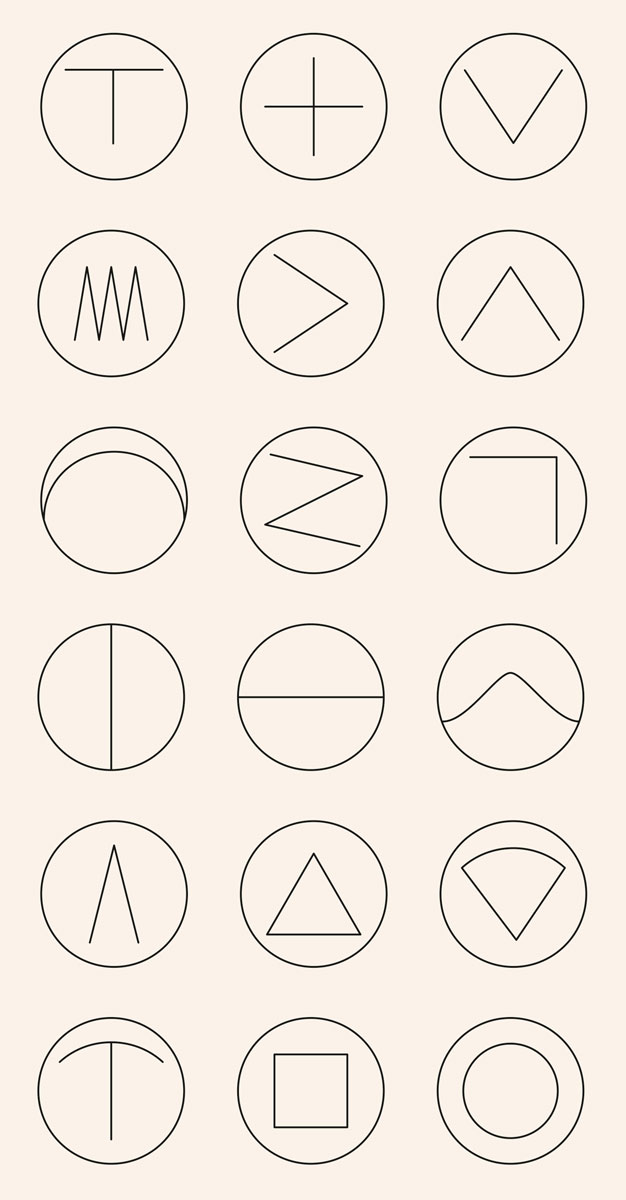

This was the first extracapsular cataract extraction operation on record. It was a seemingly miraculous procedure: when his bandages were removed after a week of bed rest, Garion could see again. Over the next forty years, Daviel performed 206 such operations, 182 of which he claimed were successful—impressive odds for the time. After he explained his method to the Académie Royale de Chirurgie in 1753, other surgeons followed suit. Over the next century, hundreds of different medical knives were designed to try to create smoother incisions, which would speed healing and minimalize the chance of infection. Surgeons developed their own signature cuts, and ophthalmology illustrations show a variety of these marks, scarred onto the cornea like runic signs or the Utopian alphabet invented by Thomas More. In one example, the doctors’ surnames and the date of each procedure are inscribed below a circle containing their patented triangle, zigzag, anchor, square, cross, circle, or V and T slit. Together they form a secret language of eyes.

Eighteenth-century philosophers were fascinated by blindness—Locke, Leibniz, La Mettrie, Diderot, and Voltaire were all interested in the intellectual problems thrown up by the new science, or art, of cataract surgery. The blind man restored to sight became a paradigmatic figure in Enlightenment thinking. “To rediscover the permanent truth of this bright, distant, open naivety of the gaze” was, according to Michel Foucault, one of the “great mythical experiences on which the philosophy of the eighteenth century had wished to base its beginning.”

In 1688 the Irish scientist and politician William Molyneux, whose wife lost her sight in the first year of their marriage, posed a question to John Locke: would a man born blind, who has learned to distinguish objects by touch, be able to distinguish a globe and a cube by sight alone if he were ever cured? After Locke wrote about it in 1690 in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, philosophers grappled with what came to be known as the Molyneux problem. However, it was only in 1728, when the London surgeon William Cheselden operated on a thirteen-year-old boy, removing the cataracts that had made him blind soon after birth, that Molyneux’s thought experiment could be practically tested.

Cheselden, working before Daviel’s pioneering surgery, used a method known as “couching” to push the opaque lens from the line of vision with a special needle. This method had been practiced, with minimal success, since antiquity. The lens, rather than the retina, was thought to be the vehicle of sight and the cataract (from cataracta, Latin for waterfall) a coagulated obstruction between it and the pupil. Though physicians misunderstood the role of the lens in vision, by working the hardened, or “ripe,” cataract away from the pupil with a sharp point, pushing it to the back of the eye or breaking it into pieces, vision could be restored.

The Cheselden boy’s “conversion” to sight (attended by a local minister) was described in almost biblical terms: “When the patient first received the dawn of light there appeared such ecstasy in his action that he seemed ready to swoon away in the surprise of joy and wonder,” wrote one witness to the patient’s Damascus moment. In the sensory confusion of first sight, the boy had no spatial sense and “thought all objects whatever touch’d his eyes.” Molyneux’s problem was therefore answered in the negative—the boy couldn’t distinguish a cube and sphere without testing them first with his hands (he had to learn to see)—but the debate still raged. Was the boy asked leading questions? Had he been given time to recover from the operation? Was he intelligent enough?

Surgeons were keen to replicate Cheselden’s success and contribute to this philosophical discussion. However, eye surgery, with its promise of dramatic cures, remained a controversial field. Operations were often performed by itinerant barber surgeons, rogue oculists who would travel across Europe and as far as Russia and Persia, performing these dangerous procedures before large audiences in the central squares of towns. One such quack doctor, John Taylor, who had in fact been trained by Cheselden at St. Thomas’s Hospital in London, would arrive in a carriage painted with pictures of eyeballs and the motto: “Qui dat videre dat viver” (He who gives sight, gives life).

Taylor treated people from all social strata, and claimed to have cured emperors, popes, and kings (including George II). It was lucrative work: if people couldn’t pay his exorbitant fees, he accepted valuables, such as gold fob watches, instead. He distributed handbills that lauded him as “Chevalier” and “Ophthalmiater Royal” and used flamboyant, occult techniques, such as administering eye drops created from the blood of slaughtered pigeons. The French surgeon Pierre Guérin described how Taylor would bind his patients’ couched eyes with gauze that included egg white, baked apple, or salt, and sometimes a coin: “He would exalt; he would proclaim a miracle; he plugged the eye with firm recommendation not to uncover it until after five or six days, and he left on the fourth, after having exploited the victims of his bad faith.”

In 1750, Taylor operated on the sixty-six-year-old Johann Sebastian Bach in Leipzig. On this occasion, Taylor was still around when the composer’s bandages were removed a week later. Having failed to restore his sight, Taylor operated on Bach’s eyes a second time and administered mercury treatment and bleeding. Rendered completely blind, and in terrible pain, Bach died a few months after his surgery from a post-operative infection. Eight years later, Taylor operated on George Frideric Handel in London with similar lack of success. Handel, who had already undergone several couching operations, spent the last decade of his life in darkness. He would cry as he listened to the aria from his oratorio, Samson (1741): “Total eclipse: no sun, no moon, all dark amidst the blaze of noon.”

Jacques Daviel’s newly invented technique, which might have saved Handel’s vision, gave some much needed legitimacy to eye surgery and remained the predominant technique until the 1950s, when ophthalmologists began inserting artificial lenses into the eye; now technological developments and prosthetics such as laser surgery, retinal simulators, and touch-sight devices offer new hope to the long-term blind. While a few charlatan cataract cutters replaced them, couching quacks like Taylor went out of business in the late eighteenth century. Taylor died in obscurity; with poetic justice, and like his many victims, he also died blind. Samuel Johnson liked to cite his career as a cautionary tale, an example of “how far impudence may carry ignorance.”

Christopher Turner is an editor of Cabinet. His book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came To America, will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the US and by HarperCollins in the UK in June 2011.