Bombweed

Blooms amid the ruins

Brian Dillon

Early in May of 1941, the English novelist and essayist Rose Macaulay travelled to the Hampshire village of Liss to oversee domestic arrangements following the death of her sister Margaret. On the 13th of May, she returned to London, where since the start of the war she had worked part-time as a voluntary ambulance driver and had lived in a flat at Luxborough House in Marylebone, in the city’s West End. Macaulay must have known—though the details were no doubt unclear—that three days earlier the city had suffered what is commonly agreed to have been the worst night of bombing of the Blitz. Several prominent buildings had been hit, including the British Museum, the Houses of Parliament, and Waterloo Station, but the night is chiefly remembered for the scale of destruction: 1,486 Londoners killed and eleven thousand houses destroyed. When Macaulay arrived in Marylebone, she found that she had lost everything.

“Forgive this dislocated scrawl,” she wrote to a friend, Daniel George. “I came up last night … to find Lux[borough] House no more—bombed and burned out of existence, and nothing saved. I am bookless, homeless, sans everything but my eyes to weep with. ... I have no O[xford] D[ictionary] … no nothing. ... It would have been less trouble to have been bombed myself.” More than anything, it was the loss of her library that tormented and changed Macaulay; her writing slowed, and she did not complete another novel for almost a decade. In 1949, in a radio talk for the BBC, she said: “I am still haunted and troubled by ghosts, and I can still smell those acrid drifts of smouldering ashes that once were live books.” But something had happened in the meantime to Macaulay’s already cynical and wry sensibility; she had become a connoisseur of the very destruction that had greeted her in 1941. In 1953, she would publish Pleasure of Ruins, her classic study of the history of ruin aesthetics, where she pictures for the reader a bombed-out house in which “the stairway climbs up and up, undaunted, to the roofless summit where it meets the sky.”[1]

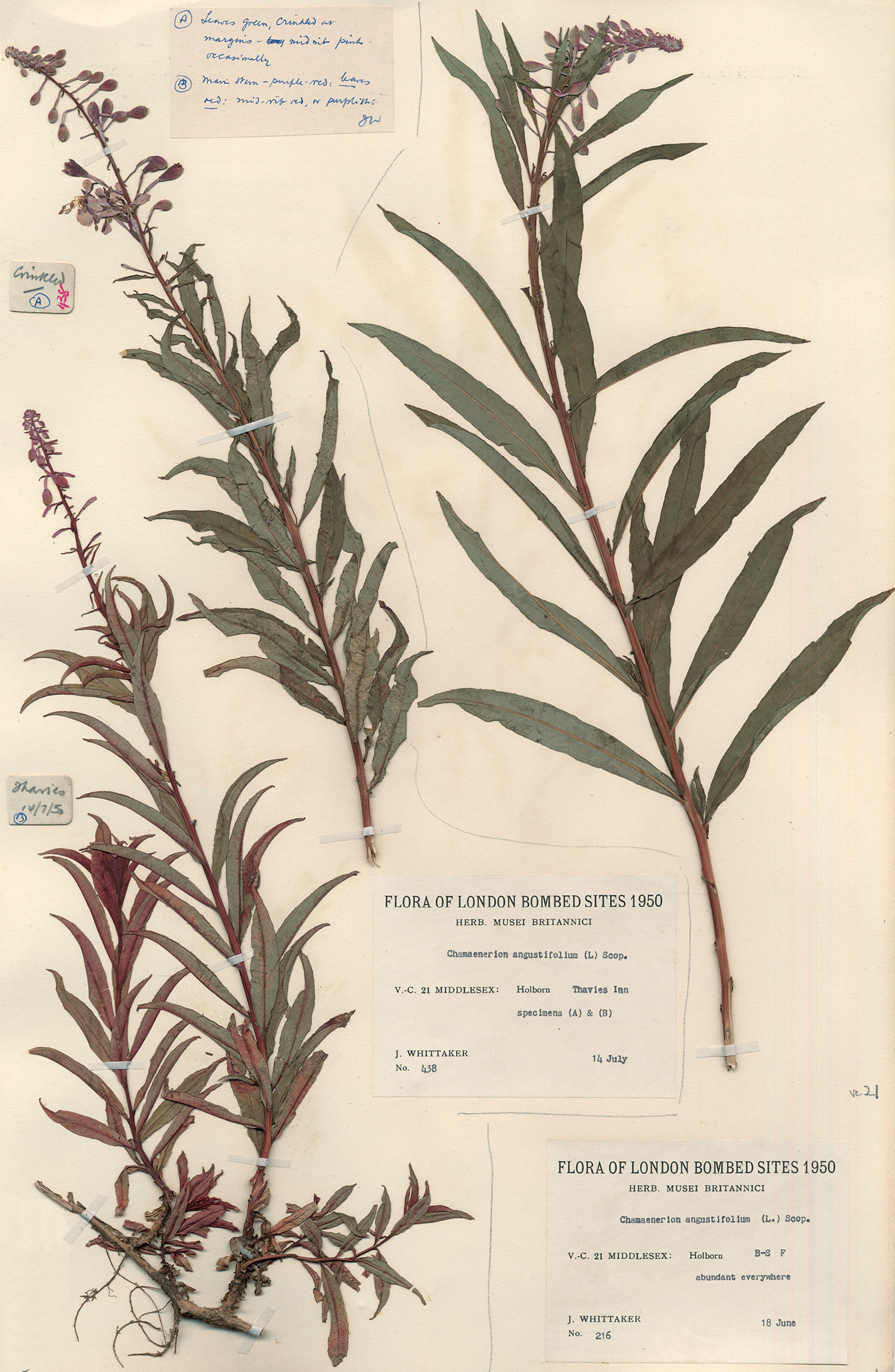

According to her friend and fellow novelist Penelope Fitzgerald, Macaulay’s ruin lust was first expressed during excursions among the debris and flora of the bombed city. Fitzgerald recalled “the alarming experience of scrambling after her that summer … and keeping her spare form just in sight as she shinned undaunted down a crater, or leaned, waving, through the smashed glass of some perilous window.”[2] London had become a fearful playground for an imagination already in thrall to T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, with its imagery of a city and culture in fragments, streams of the living dead crossing London Bridge, and new life springing weirdly from the cold earth. Macaulay paid close attention to the plants that appeared in the ruins during the first summer after the Blitz: chickweed, fennel, vetch, bramble, bindweed, thorn-apple, and thistle, among many others. But there was one species that seems especially to have haunted her, as it did other Londoners and visitors to the city: a plant that hazed the ruins in purple flowers and drifting white seed heads in the years that followed, becoming so familiar to the city’s inhabitants that, not knowing its rural name, they called it “bombweed.”