Parking Plots

Thinking sociologically about the valet booth

David Levine

Although there are probably as many open-air parking lots in America as there are parking garages, the attention lavished on the latter by architects, theorists, and urbanists means that the humbler structures which anchor our open-air lots—parking, or “valet” booths—are often overlooked.

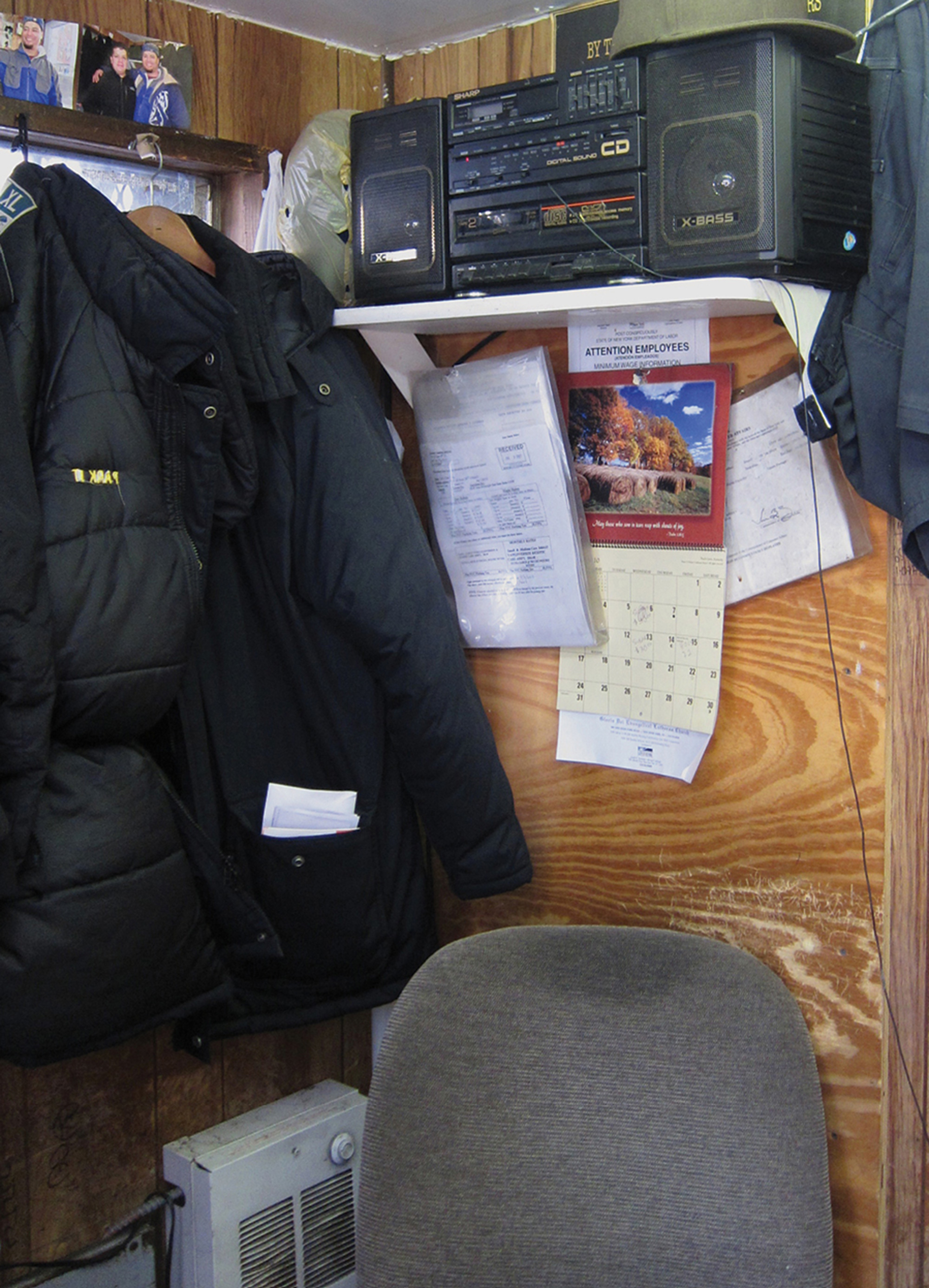

As a workplace, the valet booth, like its brethren the toll booth and the guard booth, is at once snug and anonymous. Like the guard booth, the valet booth must both shelter its occupants and discomfit them enough to ensure that they actually go outside, where the real work takes place. Unlike the sentry booth, however, the valet booth requires no physical rectitude from those employed to inhabit it; and unlike the toll booth, the valet booth never appears in multiples. Squatting alone on a huge asphalt lawn, its occupant half-visible through the window on a chair or stool, the valet booth resembles nothing so much as a little home.

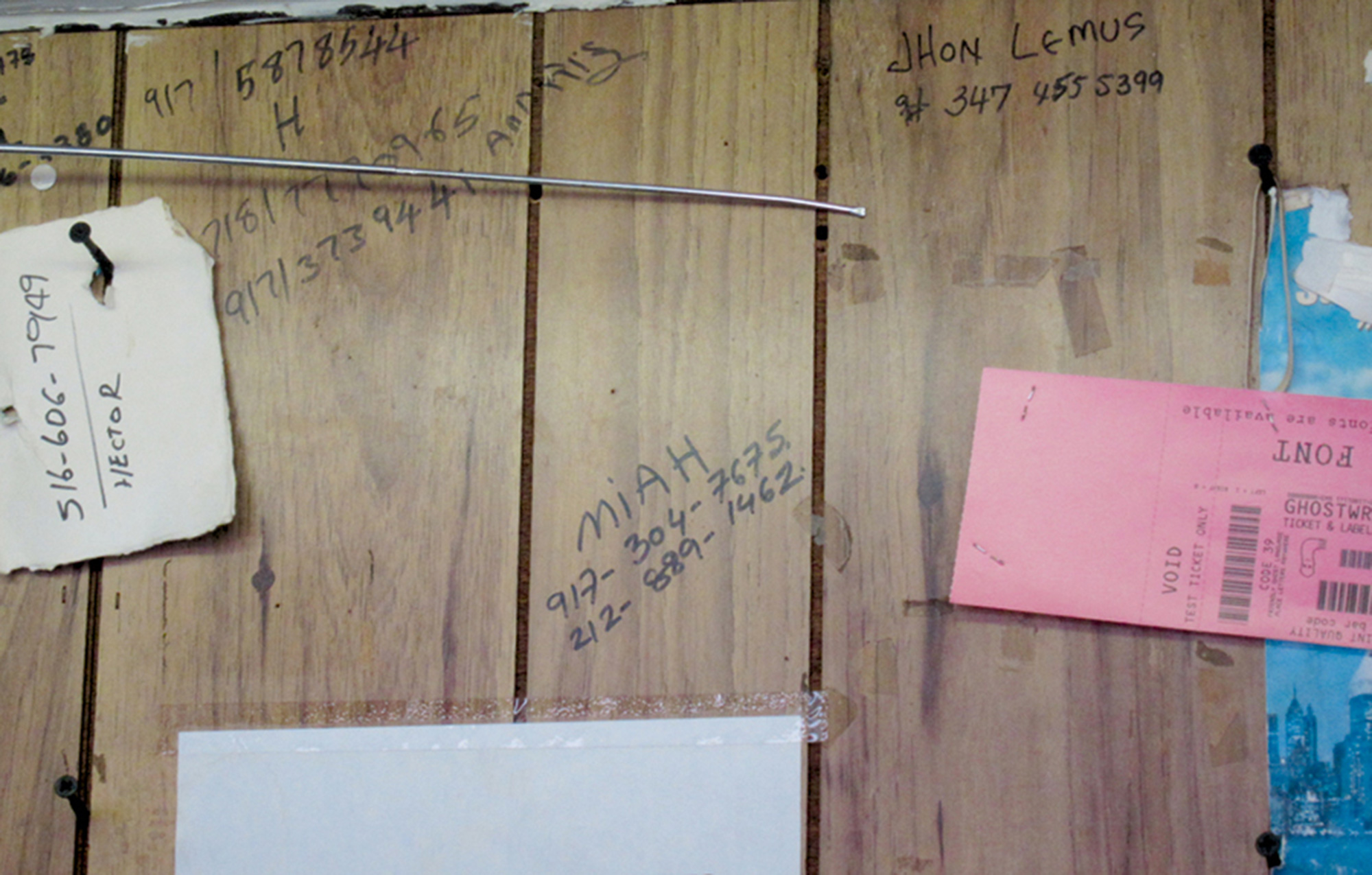

Or at least it did, from the 1970s to the early 2000s, when the valet booth was most frequently a repurposed guard booth. Already appropriated, the booth would inevitably be subjected to further minor alterations by its employees: Christmas lights hung around the windows, Pirelli calendars pinned to the walls, inscrutable graffiti scribbled everywhere. By some unspoken agreement, however, many New York City parking firms have adopted Central Parking’s black, white, and yellow color scheme for their booths, thereby lending some measure of harmony to the welter of architectural styles and interior designs.

And in the past few years, the larger parking corporations, such as Edison and Alliance, have begun to replace their random array of ramshackle booths with a more uniform and specialized set of structures, in part to accommodate more complex and efficient computer systems. Though these are undoubtedly warmer, more secure, and more spacious, one can’t help feeling that something human scaled has been lost. But this is just nostalgia, made all the more pernicious by the fact that most employees seem to prefer the new booths, which are obviously more comfortable.

David Levine is an artist who lives in Berlin and New York. His installation Habit was recently exhibited at MASS MoCA, North Adams, Massachusetts, and an artist’s book entitled Rothko Levine Stamos Reis Lloyd et al. will be published by One Star Press in 2012.