Forensic Machinery

Not so patently obvious

Alain Pottage

The idea of electrical telegraphy first took shape somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic, on a packet ship sailing from Le Havre to New York in October 1832. In the course of the six-week crossing (packet ships were made to be robust rather than fast), conversation between the passengers aboard the Sully turned to the properties of electricity and electromagnetism. A Boston chemist, Dr. Charles T. Jackson, introduced the topic with an account of recent experiments in the transmission of electricity, notably a demonstration given by Charles Pouillet in Paris, in which “an electrical spark passed instantaneously, without any perceptible loss of time, four hundred times around the great lecture hall of the Sorbonne.”

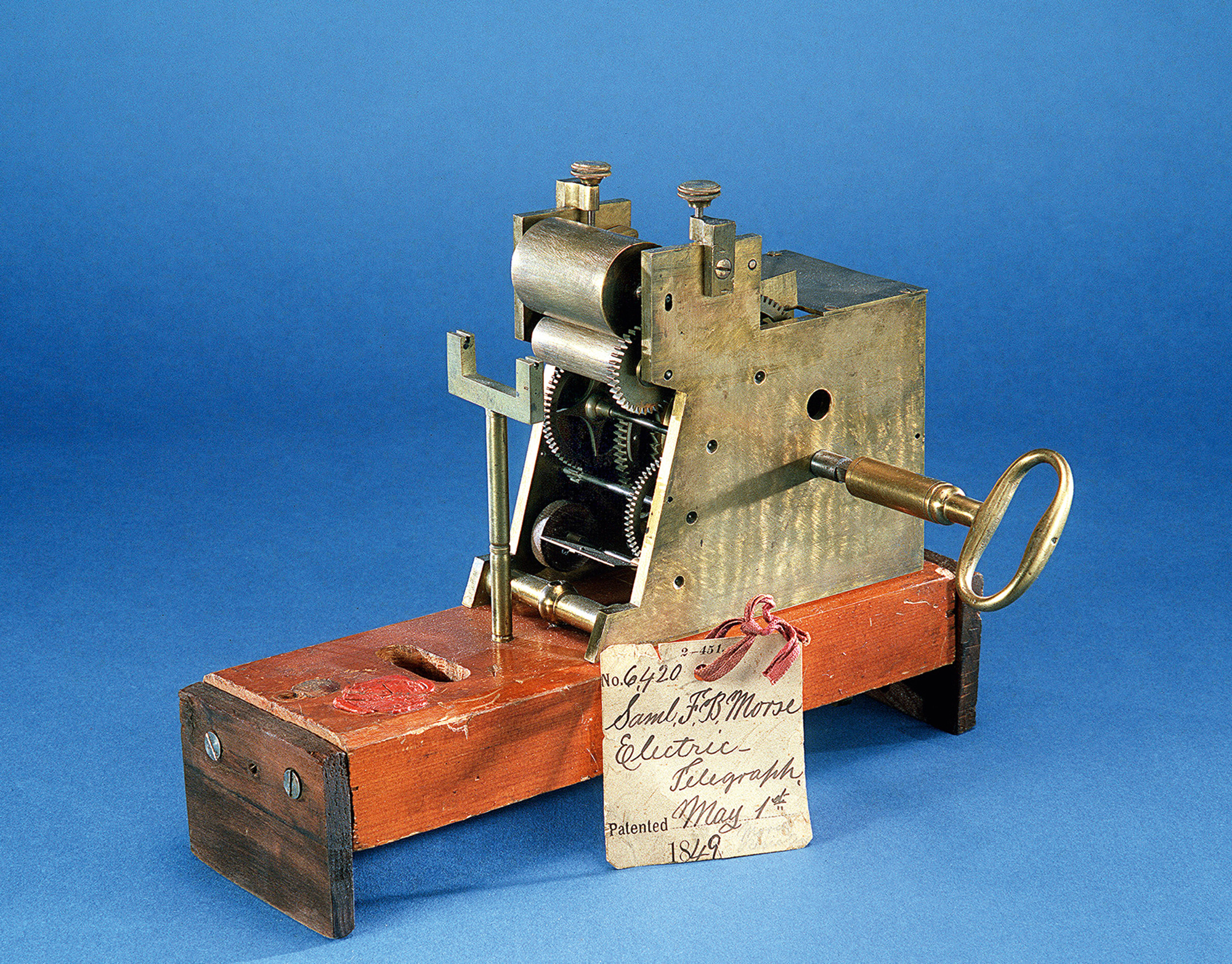

According to the received version of events, Jackson’s report awakened a “dormant inspiration” in the mind of Samuel Morse, who observed to his fellow travelers that it should be possible “to transmit intelligence instantaneously by electricity.”[1] Morse then set about making notes and sketches outlining the rudiments of the system that he patented in 1840. He canvassed the use of insulated wires to transmit signals, suggested that electromagnets might translate electrical current into mechanical action, proposed the use of a continuous paper strip to record transmissions, and formulated a code that turned dots and dashes into numbers and then letters (the alphabetical structure of Morse code was actually an invention of Morse’s collaborator, Alfred Vail).

Our theme is forensics, so we already know that this story of invention had two sides. According to Dr. Jackson, his presentation of Pouillet’s experiment had prompted a passenger to observe that it would be a good thing if news could be sent “in this rapid manner,” and that Morse’s only response was to ask, “Why can’t we?” In a letter written to Morse in 1837, Jackson claimed that he had given Morse the basic idea of telegraphic communication, and that in the course of the voyage the two had co-operated in working out the premises that Morse later claimed as his own work.[2] Ultimately, in a case brought by Morse against his business competitors years later, the Supreme Court decided that he was the “first and original” inventor of the telegraph. It reached that conclusion on the basis of arguments that drew stories such as this myth of origin into the peculiar forensic medium of a working model. As in other nineteenth-century patent cases, evidential and jurisprudential arguments were expressed in the articulations of a mechanical model. In forensic settings, the social complexities of invention were translated into a rhetorical medium that was as much mechanical as linguistic.