Mediating Time

Clocking in to the TV

Amelie Hastie

This contribution to Cabinet’s “24 Hours” issue was completed in Amherst, Massachusetts, in 22 hours, 10 minutes.

Continuous and continual, the media day fragments.

—Henri Lefebvre[1]

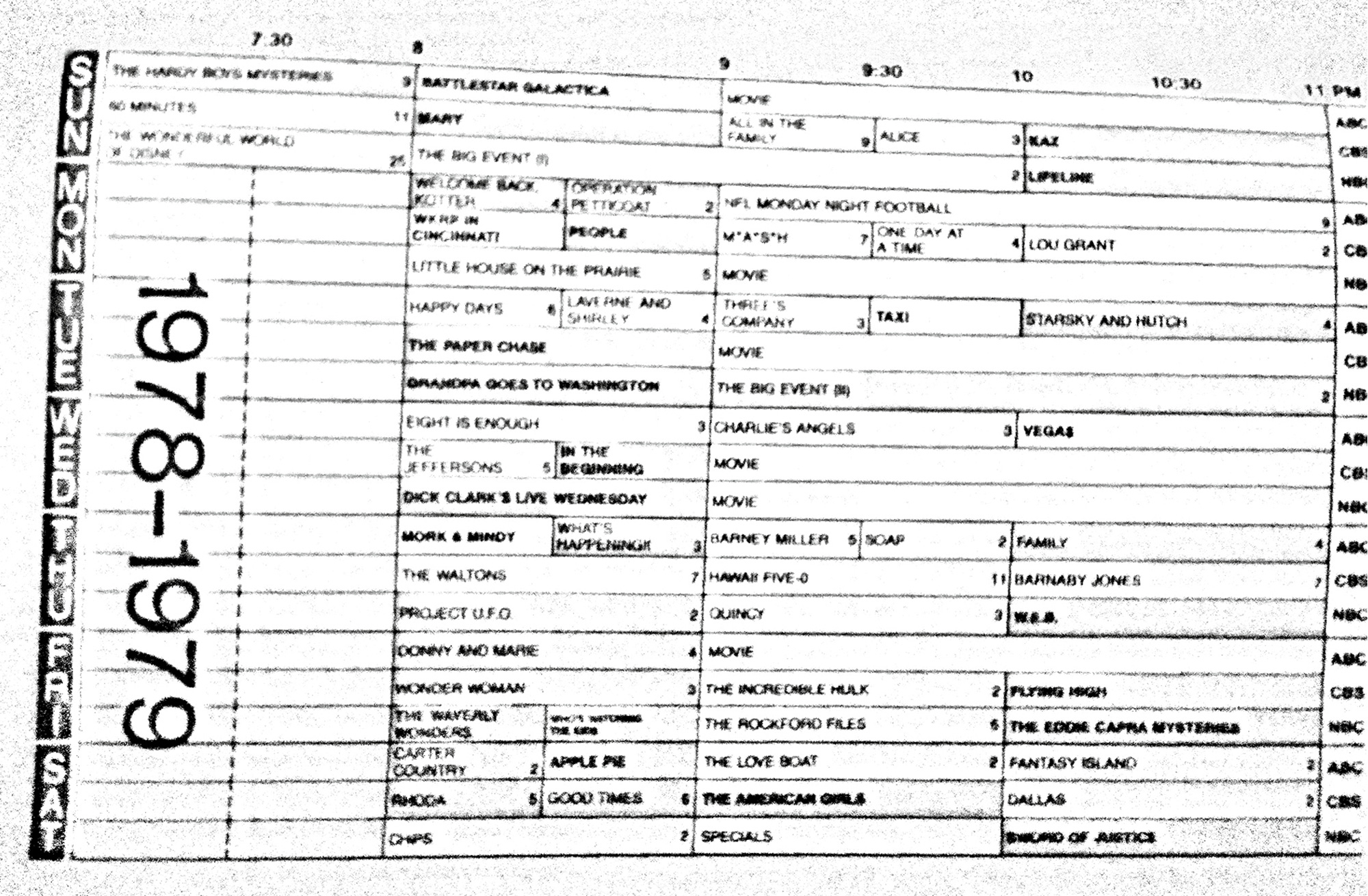

I was a TV kid. Not like Mike Teevee in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. I didn’t identify with or as television characters, and I didn’t speak only about my knowledge of television (in fact, I found it a little mortifying when I heard kids perform such monologues before class started—admitting, basically, that they spent every evening at five o’clock watching reruns of Adam 12). But I certainly told time by television: whether via Saturday morning cartoons, weekday afternoon game shows like Match Game ’75, or the Tuesday night fare of The Muppet Show, Happy Days, and Laverne and Shirley. By high school, it was daytime soaps—at least in the off-season of track and cross-country—which told me not just what time it was (2 pm for General Hospital, 3 pm for All My Children), but also what day it was (very little happened on Tuesdays, whereas Fridays, of course, had cliff-hangers). Television was a means of both managing time and passing time for me, as it was and is for so many viewers.

Television also produced in me a sense of anticipation and expectation. I remember quite clearly, in my brief heady days as a rocker chick, driving across town with the guys to our friend’s house with cable television, and therefore MTV, waiting, sometimes fruitlessly, for an Iron Maiden video before going back home across the river. A little lovestruck—not for the band, but for the boy with cable—I didn’t want the video to play. Instilled in me, perhaps, was a desire for something else. Of course this sort of experience of mediated anticipation wasn’t unique to me. This sensation and sensibility is designed by the very organization of US broadcast television. Split into fragments, as Lefebvre acknowledges, television invites us to wait for the commercial to end, the narrative to begin again; we anticipate not just a particular kind of action or knowledge but also that series which follows the one we are currently watching. And at the end of every prime-time episode, we anticipate another to come a week later. Of course, that particular form of mediated time doesn’t find its origins in television but in other serial forms, such as nineteenth-century novels, fragmented in magazines to keep the readers buying for the next installment. Given this history, we might say mass media has perfected a rhythm of waiting in its consumers and its citizens.