Class Struggle, Inc.: An Interview with Bertell Ollman

The rise and fall of a Marxist board game

Bertell Ollman and Sina Najafi

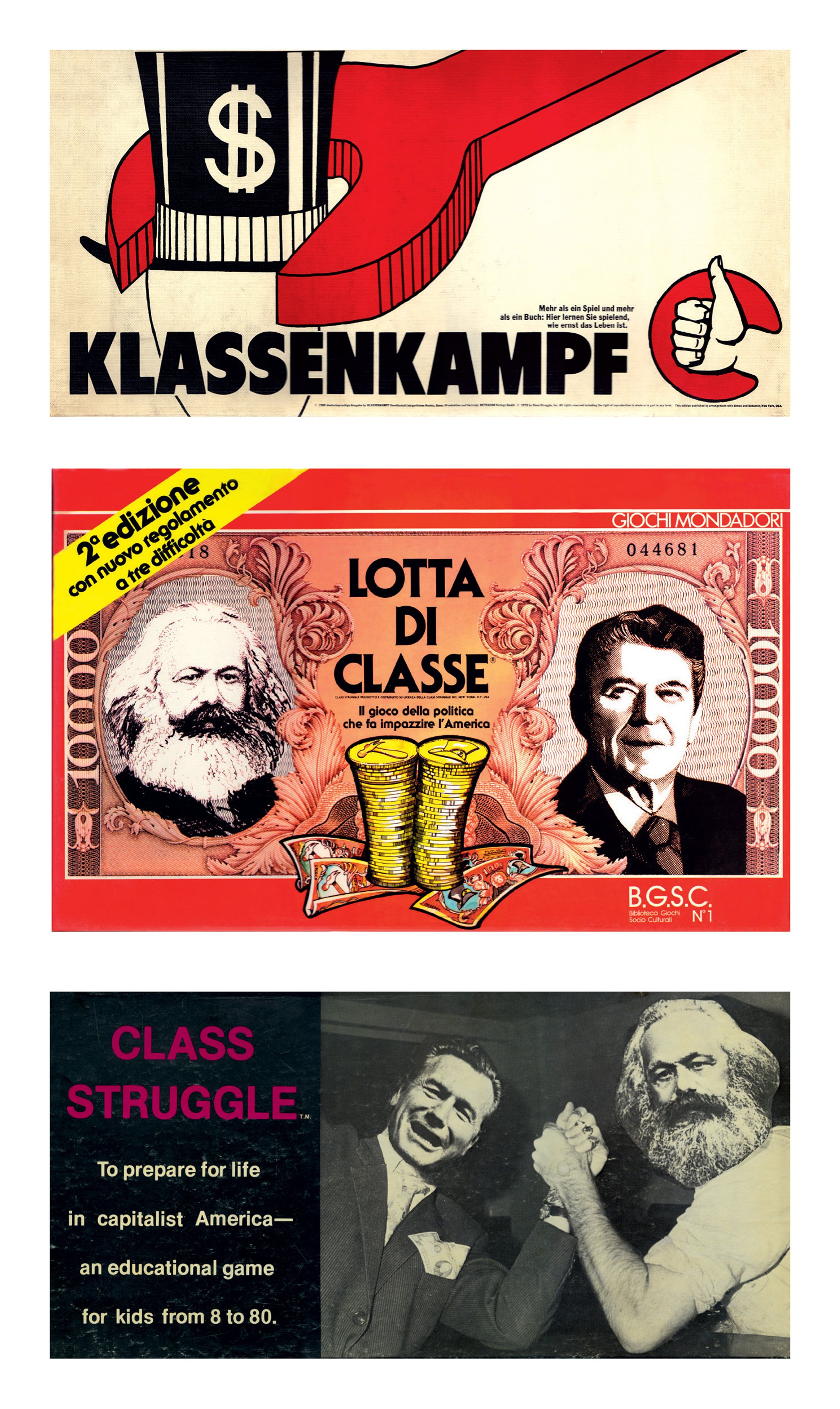

In 1978, Bertell Ollman, a professor of politics at New York University, decided to form a small company to produce and sell Class Struggle, the only socialist game ever mass-produced in the US. Class Struggle was received with tremendous fanfare by the press, both conservative and radical; almost 100,000 copies of the game were sold in the US alone, and Italian, German, French, and Spanish editions of the game quickly followed. Despite the healthy sales figures, the company struggled to make ends meet, and after a few years, the game was sold to Avalon Hill, which continued to produce it until 1993. Class Struggle, Inc.—which Ollman had set up with several friends—was dissolved in 1983.

Author of numerous books on Marxism, Ollman has also written Ballbuster?: True Confessions of a Marxist Businessman, which provides an account of his time running a company whose sole product sold almost quarter a million copies worldwide but managed to lose $15,000. Sina Najafi met with Ollman to talk to him about the game and its history.

Cabinet: Your game was released in 1978, but I know you had been thinking about it for years before that. Can you talk a little about your own formation, and how you came to think about inventing a game like this?

Bertell Ollman: Ever since I became a socialist—which happened in my undergraduate years at the University of Wisconsin in the 1950s—I have been interested in two things. One was trying to understand more about how society really works and how it could be changed in a way that, as a socialist, I thought would be better. But I was also always looking for ways to help others understand what I was coming to understand. Teaching and pedagogy were important to me and how I lived my life, and I thought of Class Struggle as a way to teach my views to people who don’t want to sit in my lectures but don’t mind playing games.

Were you a fan of board games?

I certainly played board games and my share of Monopoly, but I played sports more. When I came to New York in 1967, one of my good friends was Sol Yurick, the novelist. Sol and I spent time talking about what kinds of games were out there, and what kinds of lessons people, particularly younger people, learn from these games. I didn’t know yet how few games became successful compared to the number that appear on the market. But the ones we knew anything about were all business-oriented games, Monopoly being the best known though by no means the worst in terms of the lessons being taught. At least Monopoly never openly extolled the negative human qualities that it fostered. It was around that time, however, that a game called Lie, Cheat, and Steal came out. That was actually the name of a game! And there was a game called Counterstrike that boasted on its cover that “it brings out the worst instincts in you, from avarice to downright treachery.”

It seemed like businesses were simply supplying what could sell on the market, but was the market really that lopsided in terms of what it was calling for? I came to doubt that, especially when I learned about the history of games, because business-oriented board games were not at the center of the industry until some time after World War II. Board games are very old—they first made their appearance in ancient Sumer over 4,000 years ago—but by the late eighteenth century, a host of new board games became available that were unabashedly didactic. The games taught history, math, and so on, and, quite soon, also moral behavior. America’s entry into the board-game derby came toward the middle of the nineteenth century with Mansions of Happiness, where you try to land on squares called “Justice” and “Piety,” and avoid squares called “Immodesty,” “Cruelty,” “Ingratitude,” etc. And there were other games like this, like the Game of Christian Endeavor, where players are rewarded for niceties like “Taking flowers to the sick” and “Stopping man from beating horse.” It wasn’t until the Depression, and especially with the appearance of Monopoly, that business values began to replace Christian values as the core message of the industry.

As socialists, Sol and I were interested in finding the socialist alternatives. There just had to be games that used the inequalities of our society to criticize greed rather than exacerbate it. There were socialist books; there must be socialist games! I found one game that was mildly critical of the status quo and that was Anti-Monopoly from 1973. In this game, true to the world we live in, monopolies exist at the start, and—less true or possible, I’m afraid—players representing antitrust attorneys move around the board and break them up. It is a liberal game, focusing on the size of power concentrations rather than on the question of who holds power.

Did you look for examples in Soviet bloc?

We did. They were very hard to find and the only two I remember was a Soviet one called A Race to the Moon, which was about how the Russians were racing the Americans to the moon. This was presented as a socialist game, though I couldn’t see anything particularly socialist about a race to the moon! And in Hungary, there was a game that some considered socialist called Dacha, in which you collected furniture for your country dacha! I didn’t see that as socialist, either.

I discovered quite late in my research one board game that came very close to what I was looking for. I learned from Ralph Anspach, the inventor of Anti-Monopoly, that Monopoly itself had begun as a critique of the very system that it’s done so much to promote. The official history of Monopoly is that an unemployed Philadelphia worker named Charles Darrow invented the game in 1933 and sold it to Parker Brothers. Anspach’s research shows that the real inventor of Monopoly was a woman called Elizabeth Magie, a Quaker follower of the Single Tax economist Henry George. She invented the game in 1903 and called it the Landlord Game. She had a good introduction that attacked the landlord and she had labeled the different squares with names that suggested where she was coming from. So, for example, there was the Soakum Lighting Company, Lord Blueblood’s Estate, and so on. A 1925 version of her game, by now called Monopoly, had an introduction that said: “Monopoly is designed to show the evil resulting from the institution of private property.” But the actual mechanics of the game moved in the opposite direction. She had created every player as equal; they all got the same amount of money; they all moved toward winning the game by building as much property on what they owned; and if you drove the others to bankruptcy, you won.

How did this story of a game like Landlord—one that was meant to critique the social order, but that ended up, with a few cosmetic changes, being repackaged as the Monopoly we know now—affect the way you developed your game?

The frightening story of the metamorphosis of the Landlord’s Game into Monopoly gave new urgency to our question: What was a socialist game, anyway? Maybe there were no socialist games because it’s impossible to have one. After all, for a game to be fun to play—and no one would invent a game unless it were fun—you’d have to give everyone more or less the same chance to win. In our view, the deck was stacked, so maybe that made it impossible to invent a game that was true to what socialists believe, one in which all the players have an equal chance to win. Maybe that was the problem.

So we started thinking more about the mechanics of gaming. What kind of mechanics would make it possible to make a game that presented socialist views of our society? Finally I hit on the idea: what if the players in the game were not individuals but classes? In my favorite socialist novel, The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, Robert Tressell has his working-class hero adopt such a ploy in a charade he plays with his fellow workers to explain the labor theory of value. I had restaged this scene many times in my NYU classes.

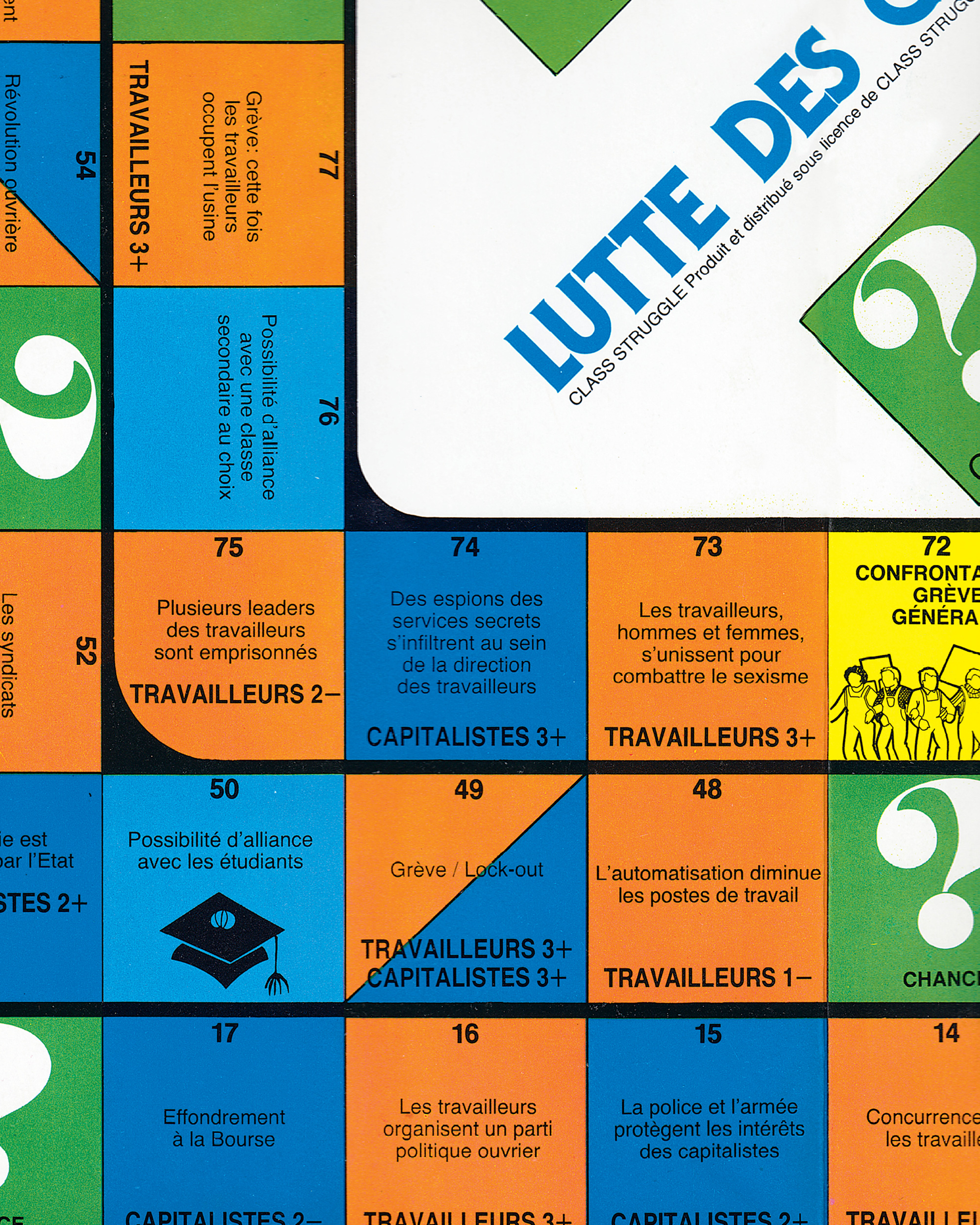

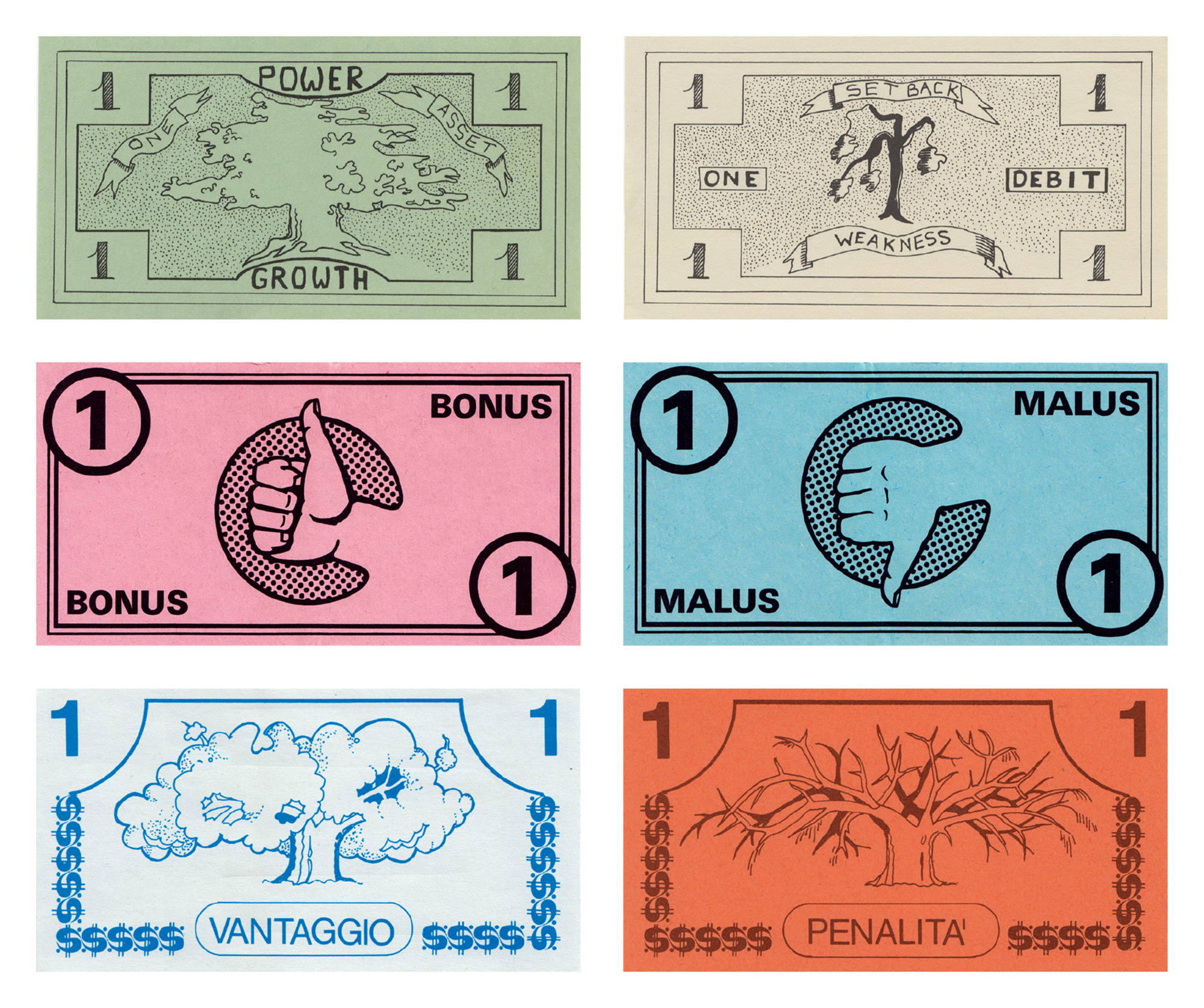

Would it work in the game? The two main players would represent the capitalists and the workers, and they could be roughly equal in power. Of course the sources of their powers had to be very different and one could talk about the advantages and disadvantages each class has in the ongoing struggle to promote its own interests in a zero-sum game. Would it be possible to look into the variety of conditions that are good or bad for either class and to make those into the material that the classes are trying to collect in order to win the class struggle? The high points of the struggle could then be broken down into steps or stages. The earliest stage could be an election; a middle stage, a general strike; and a final stage, a revolution. In this way, Class Struggle started to come together.

Of course, we spent a lot of time trying to make it more interesting in terms of not having it all depend on chance, but also on strategies of various sorts. And so we started to think of minor classes and class alliances, which would increase the power of one or the other of the two major classes in their confrontations. I tried to work my ideas about socialism into the chance cards and into the game rules, so that everything in the game came to reflect some truth about how capitalism really works.

I did make a few compromises in how I understand capitalism. For example, students are not a class. I needed four minor classes that people knew about. “Small business” was easy; “Professionals” was easy; “Farmers” was easy. But students belong to the class that their parents are in, and then they join the economy and belong to a class based on what they end up doing. I felt very uncomfortable using them, but I realized that most of the people playing would be students and this was a way to connect to them. But if as a political theorist, I were to look at this game, made by someone else, I would in fact criticize the terrible mistake they made in treating students as a class. The second mistake I made is that I played up too much the ability of the minor classes to decide what alliances to go into. In reality, the pressure on them to align themselves with the capitalists is usually very strong.

Why did you do this?

I had to have something that would involve wheeling and dealing, and allow different players to think about strategies. As a Marxist political theorist, I am uncomfortable about the whole thing with alliances in the game.

How did friends and colleagues, especially others on the left, react to the idea that you were going to produce a game like this?

There were a number of friends who thought that class struggle is too serious a matter to be made into a board game, that the game trivialized the suffering that people undergo as a result of class struggle. They were not doubting my commitment, but they thought that it was a terrible mistake. I was a bit shocked by this.

If you were to do a new edition of the game, do you feel that there are things that you would do differently? Are there things that you would update, for example, to take into account all the changes between the late 1970s and today?

That’s a good question. My wife, who was a part of the discussions from the beginning, thinks that if the game were to be updated, I’d have to bring in an awful lot that has happened, not just in America, but globally—things like globalization, the role of financial capital, maybe even some of the wars that have occurred since. My answer is, No.

Let me explain why. One of the most important and least understood features of Marx’s analysis of capitalism is that it takes place on a few overlapping levels of generality. We all have characteristics that make us distinctive as unique individuals. This is what allows me to say hello to you on the street, to recognize you. We also have other characteristics that distinguish us from other kinds of animals and give us our human identity. Let’s give these numbers. We’ll call our unique qualities—everything specific that gets people to recognize you—level 1. On the other hand, we’ll call what allows us to recognize every human being as a human being, compared to every other animal, level 5. In between those two is level 3, which focuses on the qualities that we all possess because we live in a capitalist world, which divides us all up into the classes peculiar to capitalism and gives each of us special interests and functions depending on the class to which we belong. These are completely separate from our qualities as unique individuals and our character as members of the human species.

Your question has to do with level 2, which brings into focus the characteristics that accrue to us, but also to all our activities and products, because we live in a specific stage of capitalism, which is now the stage of financial capital. There have always been some kind of banks and debt, but now the financial sector has come to dominate the capitalist class, and that has created special conditions and problems for capitalism. Most of Marx’s writing is about level 3; it’s about those characteristics, conditions, and relations that are distinctive of capitalism as an era ranging from roughly 1500 or so to the present. His main purpose is to analyze what he calls the laws of capitalist development, which doesn’t mean that there are not all sorts of ways for individuals to make differences and make certain choices. But these laws establish the main the alternatives between which people have to choose; you can never choose what’s not there to be chosen. These laws also play an important role in socializing people to want the kinds of things they do.

But of course you also have to recognize that each stage has certain important differences. What has changed is the most recent stage of capitalism, the modern version of capitalism, bringing us globalization and all sorts of technological achievements, and the difference that they have made in our culture and in our lives. Obviously, these were not around when Marx was writing, but the basic structures of capitalism, of capitalism in general, of level 3, remain the same. It’s important not to sacrifice one of these levels of generality for the other, or to confuse them with each other, before we set out—as we must eventually—to analyze their relations. I never thought that I could put what I have just tried to explain to you into the game. Instead, what I tried to do in the game is emphasize the more general characteristics of capitalism, which is what Marx himself did, because it is what is most important, so that there is not much in the game that is distinctive of either Marx’s version of modern capitalism or our own.

If you emphasize too much the content of the current stage, the role of financial capital, for example, there is a danger that this opens the door for a reformist approach to politics, which imagines that if we just change the role of banks, somehow everything will be fine. We’ll go back to the good old days of industrial capitalism where the industrial moguls made the key decisions.

Can you talk a little about the economics of the game itself? I was very surprised to read that, in some sense, the game was most successful in Italy, where it sold 95,000 copies—the same number as in the US, but in a much smaller country. Do you think certain countries were more receptive to the game than others?

No, it’s all about distribution. Why did the game sell well in Italy? Because it was put out by Mondadori. They were not only one of the biggest publishers in Italy, but they also had the largest chain of bookstores. For some reason, the CEO got interested in the game, and they had it in all the bookstores. You could not avoid seeing it in Italy. Mondadori were also associated with a range of bourgeois newspapers, which all had stories about the game, as did all the radical newspapers. When I traveled to Italy for a press conference for the launch of the game, they had a big hall there with a hundred journalists from all over Italy.

Of course, people at the time thought I was making millions of dollars. That was because they looked at the hundreds of press clippings from all over the world, almost all positive and from some of the biggest, most conservative papers. But the truth is that we were always on the verge of bankruptcy.

Your book Ballbuster? describes some of the effects—both funny and terrifying—that trying to run a small business had on you and your relations with your friends and business partners. It was harrowing to read your daily struggle just to survive. What made you want to write a book after the company folded and you’d moved on?

I kept notes during the whole thing, and I thought I had an interesting story not only about the history of the game, but also about small businesses and what happens even to radicals when they run a small company. It was also a very honest autobiography. I could see what was happening to me. I was grinding my teeth at night; I couldn’t get the game and all its problems out of my head. And it was affecting my relations with everyone around me, including friends and family. I didn’t think like a businessman, but I was forced to act like a businessman, and more and more, that role became me. It never completely became me otherwise I could not have gotten out, but I could see it was taking over.

None of us thought we’d get rich, but all of us were committed to making the game work, because if you think about the game as a book in disguise—a book that you read by picking up chance cards and reading the rules—then this book on socialism was read by more people than practically any other book on socialism that’s been published in the United States.

One of the strangest never-made films of all time must be the one you discuss in the book, where Warner Brothers bought your story to try and make into a Hollywood film. Can you explain how that came about?

In March 1979, the New York Times published an op-ed article of mine that they entitled “A Marxist Turned Capitalist Finds Bottom Line Too Low.” In it, I sketched how going into business had affected my health, sleep, food, family, friends, and conversation, and expressed sympathy for others caught up in the capitalist role. My conclusion was that a society that was no longer dominated by the search for profits could not help but benefit capitalists, as human beings, as well as workers.

The next day I got a call a call from a movie producer called Louis Allen, who had produced Fahrenheit 451 and Lord of the Flies. He said that there had never been a movie about a Marxist game inventor, or a Marxist businessman for that matter. I was skeptical but, after a lot of discussion with friends, I ended up agreeing to sell them my story.

When I finally got a copy of the script in January 1981, it was such a shock to see what they turned the story into, but I was in no legal position to do anything about it. The script was about a Marxist professor called Marcel Gabrilov who invents a board game called Class Struggle. The business goes gangbusters from the start—capitalists all have a great sense of humor. Everybody loves the game, especially the games buyer at Bloomingdale’s, who also falls in love with Marcel. The real class struggle in the script is between working-class Marcel and uppity Miss Bloomingdale’s. It was a soft-core romance. Marcel’s politics are mush, He is also a sexist, and his friends are all idiots. The language was full of clichés. Need I go on?

Luckily, the film was finally canned. Looking back at the adventure as a whole, what are your thoughts now? Do you regret doing it?

My direct involvement in producing and selling the game lasted about three years, but the effects of the whole experience took much longer to wear off. I could probably have written one or two more books—which I like to think could have been important—if I had not done the game. In the final analysis, as a scholar, I think I paid a price. But as a political activist and as a promoter of socialist ideas, I like to think I helped raise, if only a little bit, the consciousness of many young people to the possibility and desirability of a socialist future, and, in highlighting the idea of class struggle, helped them see the road to get there.

Bertell Ollman is a professor of politics at New York University. In addition to creating the board game Class Struggle, he has written and edited numerous books, including Alienation: Marx’s Conception of Man in Capitalist Society (Cambridge University Press, 1971), How to Take an Exam ... and Remake the World (Black Rose Books, 2001), and Dance of the Dialectic: Steps in Marx’s Method (University of Illinois Press, 2003).

Sina Najafi is editor-in-chief at Cabinet.