The Architecture of Psychoanalysis

The consulting rooms of Ernst Freud

Volker M. Welter

Anyone seeking psychoanalysis in Berlin during the 1920s had to choose between a private practitioner and a clinic. A search might have started with a visit to Karl Abraham, who practiced in the city’s Grunewald neighborhood until his death in 1925, and continued in a wide, circular sweep through the western parts of the city, meeting along the way Hans and Jeanne Lampl in Dahlem, Sandor Radó in Schmargendorf, Max Eitingon in Tiergarten, and, back in Grunewald, René A. Spitz. If these consultations were unsuccessful, there was still the Poliklinik für Psychoanalytische Behandlung nervöser Krankheiten on Potsdamer Strasse and, after 1928, in new premises on Wichmannstrasse, both in the Tiergarten district. Or, for a longer stay, Ernst Simmel had opened the psychoanalytical clinic Sanatorium Schloss Tegel in 1927. Possibly unbeknownst to our hypothetical patient, the search would have taken him through a sequence of modern psychoanalytic interiors designed by Ernst L. Freud (1892–1970), the youngest son of Sigmund Freud and a successful domestic architect in Weimar-era Berlin after 1920 and in London after 1933.

From the late nineteenth century onward, the name Freud had gradually become identified with psychoanalysis, but in the 1920s, at least in Berlin, the name was also synonymous with the creation of the earliest documented architect-designed psychoanalytic consulting rooms. Intellectually, Sigmund Freud’s conception of psychoanalysis has long been recognized as a major contribution to Western modernity. Architecturally, however, his consulting room and adjacent study at Berggasse 19 in Vienna illustrated all that his progressive contemporaries, such as Arts and Crafts architects and hygiene reformers, believed was wrong with late nineteenth-century domestic interiors. Cramped with furniture and filled with antiquities, statues, books, oriental rugs, artworks, and aromatic cigar smoke, the rooms were sensuously rich and offered plenty of opportunities for one’s thoughts and gaze to sojourn, but also for unhygienic dust to settle.

Compared to his father’s quarters, consulting rooms designed by Ernst Freud were free from visual clutter, abundant artwork, decorative figurines, and oriental rugs—a visual clarity that, however, was perhaps not unique to the architect. For example, in the mid-1920s the Santa Barbara psychoanalyst Pryns Hopkins described the London consulting room of Ernest Jones as “large, but unlike that of his mentor, Freud, it was nearly bare of furniture and gloomy.”[1] At first glance, the rooms by Freud appear as if he had deliberately sought to separate himself architecturally from his father’s legacy. He conceived couches with clear geometrical lines, experimented with their position within the rooms, developed purpose-made chairs for the psychoanalysts, and combined these pieces with, perhaps, an engraving or two of the founder of psychoanalysis, a writing desk with a chair, a net curtain, and a potted plant. Judging from the few surviving black-and-white photographs, Ernst Freud’s psychoanalytic rooms come across as almost inconspicuous modern designs, delineating an interior that obviously aimed to impress itself as little as possible on the patient’s mind. Yet on further inspection, the consulting rooms show that despite all the stylistic differences, Freud had studied closely the setting of his father’s consulting room and adapted those elements that the elder Freud had identified as essential for the psychoanalytic space.

Concurrent with contemporary psychoanalytic practice, the younger Freud conceived two types of consulting rooms. One was for private practices, usually located within or attached to the psychoanalyst’s home. This set-up followed the tradition established by his father. The other was for the emerging professional setting of psychoanalytic clinics, where rooms were used by several psychoanalysts. Six designs by Freud for private consulting rooms and four designs for clinic settings in Berlin and London are known to us. None of the private rooms can be reconstructed in its entirety from images and drawings. In most cases, photographs either do not exist or have not survived, and Freud’s drawings of the arrangement of consultation couches are usually so minimally inscribed with details such as names of clients, locations, and dates that they provide little guidance.

On 14 February 1920, the world’s first polyclinic for the psychoanalytic treatment of nervous diseases opened at Potsdamer Strasse 29 (today no. 74) in Berlin. Located just to the south of the Landwehrkanal, the polyclinic was slightly inconvenient for visitors, who had to make their way up to the fourth floor. Regardless, Eitingon and Abraham were satisfied with the premises. Both men spoke highly of Freud’s interior design for the institution, which was, incidentally, within walking distance of the architect’s home at Regentenstrasse 11 on the other side of the canal. Eitingon had financed the enterprise and as part of his support for Freud, the latter was asked to refurbish the interior. Two months before the clinic opened, Eitingon commented in a letter to Sigmund Freud that his son was helping “us very thoroughly with the furnishing of the polyclinic, he designed the furniture for us, found good craftsmen, and is supervising all the work.”[2] Four weeks after the opening, Abraham reported to the elder Freud that “Ernst ... has won lasting recognition for himself with his design for the polyclinic, which is admired by everyone.”[3] And a visitor described the clinic in 1926 in the pages of the Psychoanalytic Review as comprising “four rooms ... located on the fourth floor of an unassuming apartment house near the centre of Berlin” with each room “furnished only with a simple cane couch, a chair and table.”[4] Photographs seem not to have survived, if any were ever taken, nor do we have any information about the color scheme.

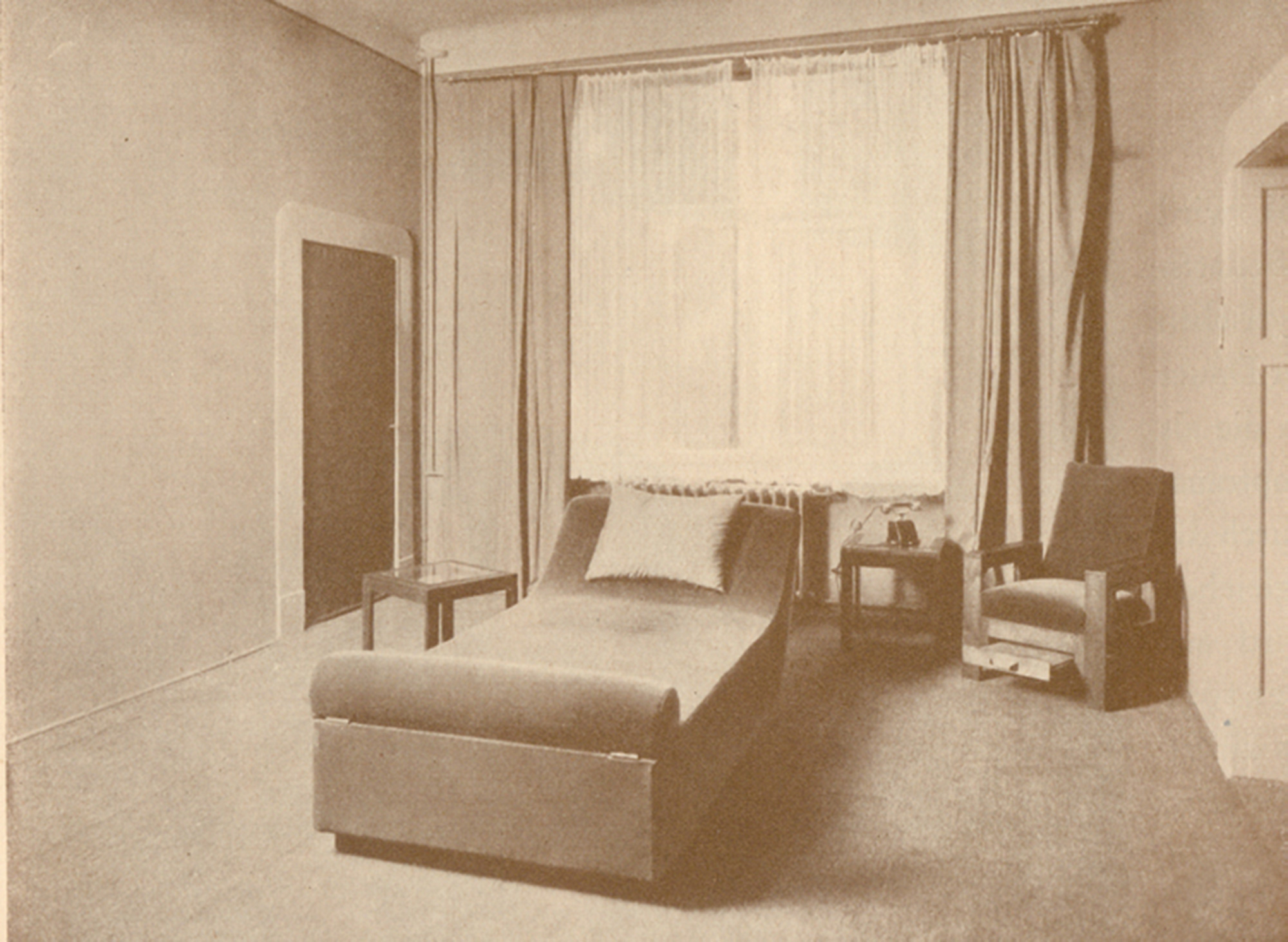

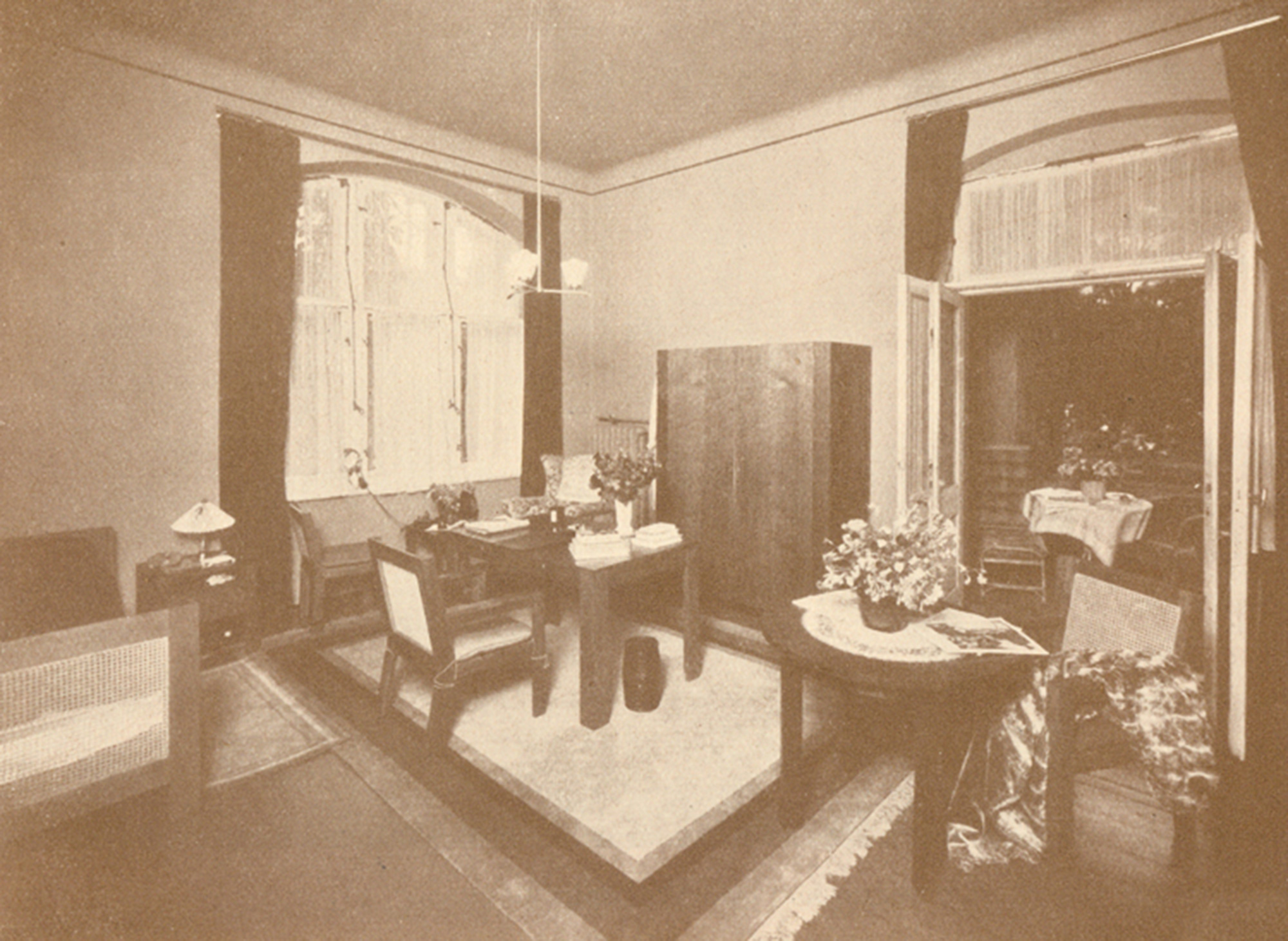

In autumn 1928, Freud was asked to design a second interior for the polyclinic when it moved to new premises at Wichmannstrasse 10. When the polyclinic celebrated its tenth anniversary in 1930, it published a Festschrift illustrated with photographs of some of Freud’s interiors. One of the images shows a treatment room; its polished wooden floor is not covered by a rug and the walls seem to be simple painted plaster. Next to a window with a net curtain sit a small desk and a bentwood chair placed at a forty-five-degree angle in the corner of the room. The chair has curved armrests and a circular seat and appears to be the Thonet B3 model derived from a design by Otto Wagner for the Postal Savings Bank in Vienna. To the left, a plant is just visible; to the right, in front of a door behind a dark curtain stands an upholstered chair turned slightly towards the viewer. Next to it, parallel to the wall, is a couch with the upholstered headrest closest to the chair. A small photograph of Sigmund Freud hangs to the left of the dark curtain, almost above the desk.

Another photograph gives a glimpse into the consulting room for the doctor on duty, a large space with a bow window facing the street. A cupboard with glass doors in the upper half and wooden doors below takes up the left wall. Near the bow window, four chairs surround a small table. To the right stands the analyst’s chair, followed by the couch placed parallel to the wall and partially hidden from view by a projecting pillar. The chair and couch are of the same type as those in the smaller treatment room. A picture hangs above the couch and three others are above the cupboard; the central image is an engraving of Sigmund Freud after a 1926 portrait by Ferdinand Schmutzer.

The setting of couch and chair in the consulting rooms of the polyclinic closely followed Sigmund Freud’s instructions about their placement with respect to each other as set out in the 1913 essay “On Beginning the Treatment.” Portraits of Freud were, of course, a new addition to the ensemble, a practice also seen in the photographs Edmund Engelman took of Anna Freud’s Berggasse 19 consulting room in 1938. These portraits gained additional visual importance due to the otherwise uncluttered and orderly appearance of the rooms. With the exemption of a conference table in a third room, Ernst Freud used mass-produced, modern bentwood chairs and light fittings. The latter added a distinctly modernist, if not to say avant-garde, note to the interiors because the architect chose a PH-lamp by the Danish designer Poul Henningsen.

The most ambitious endeavor of the fledgling psychoanalytic movement in Berlin was, however, the Sanatorium Schloss Tegel, which opened on 11 April 1927. It was the brainchild of Ernst Simmel, who had first used psychoanalytical principles while treating soldiers for battlefield neuroses during World War I. The clinic was born out of his interest in stationary treatment, which was designed to remove the patient from his daily life. It was located within the grounds of the Humboldt-Schloss, also known as Schloss Tegel. In 1906, a private medical clinic, Kurhaus Schloss Tegel, had been established on the site. It offered medical treatments, physical therapy, and psychological advice, especially for chronic illnesses and nervous diseases. Kurhaus Schloss Tegel was a new, four-story sprawling compound, whose many towers, turrets, balconies, bow and oriel windows, and partially exposed timberwork evoked romanticized notions of medieval Germany. Nearby outbuildings with water basins and surrounding gardens allowed the patients to take in both the waters and fresh air while performing healthy gymnastics.

Initially, Simmel had contemplated purchasing the building—to which end Freud surveyed it, concluding that refurbishment and modernization would require significant expenditure.[5] Instead, Simmel rented it, and the changes Freud made to the décor can be gleaned from an inventory that was drawn up when the sanatorium collapsed financially in the aftermath of the economic crisis of autumn 1929. The Berlin department store N. Israel, a specialist supplier to hospitals and hotels, built from Freud’s designs twenty-five daybeds, twenty-four cupboards, and twenty-two bedsteads, night stands, writing desks, and shelves. Three treatment rooms were equipped with couches, chairs, and small tables with glass tops, again made according to designs by Ernst Freud. Other furniture was for a villa for Simmel and the medical staff—communal dining rooms, lounge, waiting rooms, and office spaces. A Citroën car completed the inventory.

A promotional brochure for the sanatorium was illustrated with Freud’s interiors, in particular those of a single bedroom, a double bedroom, and a treatment room. The two private rooms show fully developed Freudian interiors, even though they were located in an institutional rather than a domestic setting. The floors are linoleum, covered partially by geometric-patterned rugs. All furniture is made from wood, with cane used occasionally, and is composed of clear-cut geometric forms. Remarkable is the emphasis the accompanying text places on the different colors of the rooms and the straight, geometrical forms of the furniture; both are considered to contribute to the healing process. The therapeutic process was considered to be furthered by designing the private rooms to simulate domestic spaces that thrive on activity—such as living rooms, studies, and home offices—rather than settings, such as bedrooms, typically associated with passive forms of relaxation.

The treatment room, by contrast, is much more serene. The most prominent feature is the couch that stands freely in the center with a small side-table adjacent to its headrest. Sigmund and Anna Freud both positioned their couches next to a wall in their respective consulting rooms. Ernst would adopt this placement when he designed the second Berlin polyclinic; the precise arrangements in the original location are not known. But in the Tegel sanatorium, the couch was put in a much more exposed position in the center of the room.

Too few images of contemporary consulting rooms exist to decide if this position was new or widely accepted. In 1938, when the British architect Christopher Nicholson designed a consulting room for Rosemary (Molly) Pritchard, he proposed a comparable location for the couch.[6] Pritchard’s couch was placed diagonally in front of a fireplace with the head end oriented toward a free-standing, curved screen that prevented views of the couch from the door. The position of the couch had in fact been theorized in the English context by psychoanalyst John Rickman. During the 1940s, when training students, Rickman used a small model of a couch and paper strips symbolizing the walls of the consulting room in order to discuss different options for where to place the couch.[7] As late as the 1950s, setting the couch in a free-standing position was referred to as a “break with tradition.”[8]

The consulting room in the Tegel sanatorium also changed the spatial relationship between patient and psychoanalyst by repositioning the latter’s chair. The chairs of Sigmund Freud, Anna Freud, and of the second Berlin polyclinic were positioned next to the head end of the couches. In the two Viennese consulting rooms, the chairs stood immediately behind the head end of the couches and, because they were oriented perpendicularly to the latter, the patients were outside the direct field of vision of the psychoanalyst and vice versa. The setting in the second polyclinic likewise placed the psychoanalyst behind the patients, but now rotated thirty degrees toward them; although turned more toward the couch, the patient was still not in the analyst’s direct line of sight. In Simmel’s sanatorium, the chair is placed at a similar angle to the couch but in the corner behind it, and thus much further away from it. Accordingly, a patient was now within full view of the psychoanalyst. Nicholson’s design goes even further by putting the chair in the corner diagonally opposite the couch, though the resulting wide field of vision from the chair is somewhat interrupted by the curve of the screen. These were apparently isolated, little-known experiments with the spatial setting of psychoanalysis. Trygve Braatøy’s 1954 handbook Fundamentals of Psychoanalytic Technique recommends placing the chair away from the couch and at a 120-degree angle to it in order to ensure both aural and visual contact with a patient; fellow psychoanalysts reacted to this proposal fearing “a revolution or complete turnabout of their position.”[9]

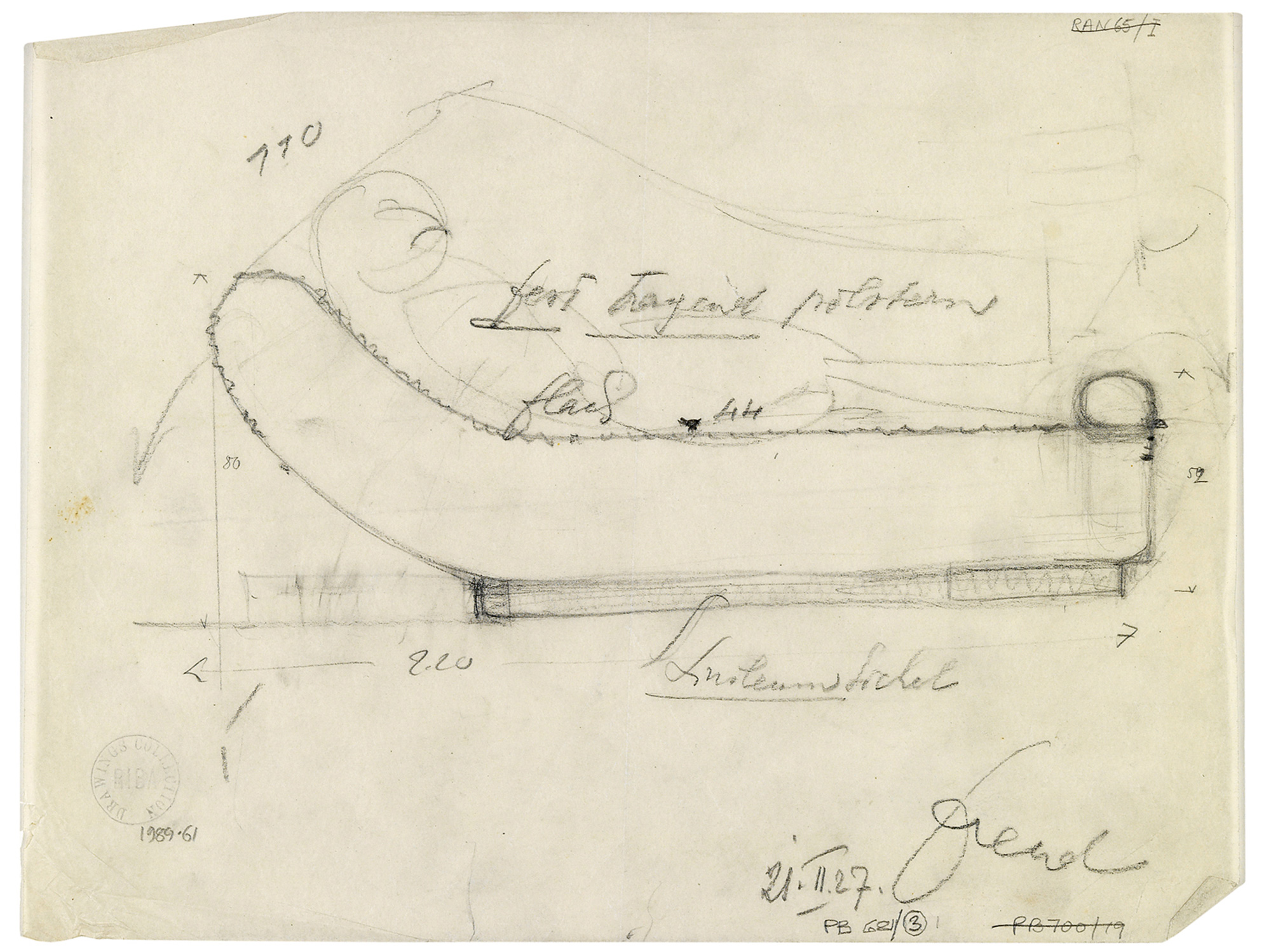

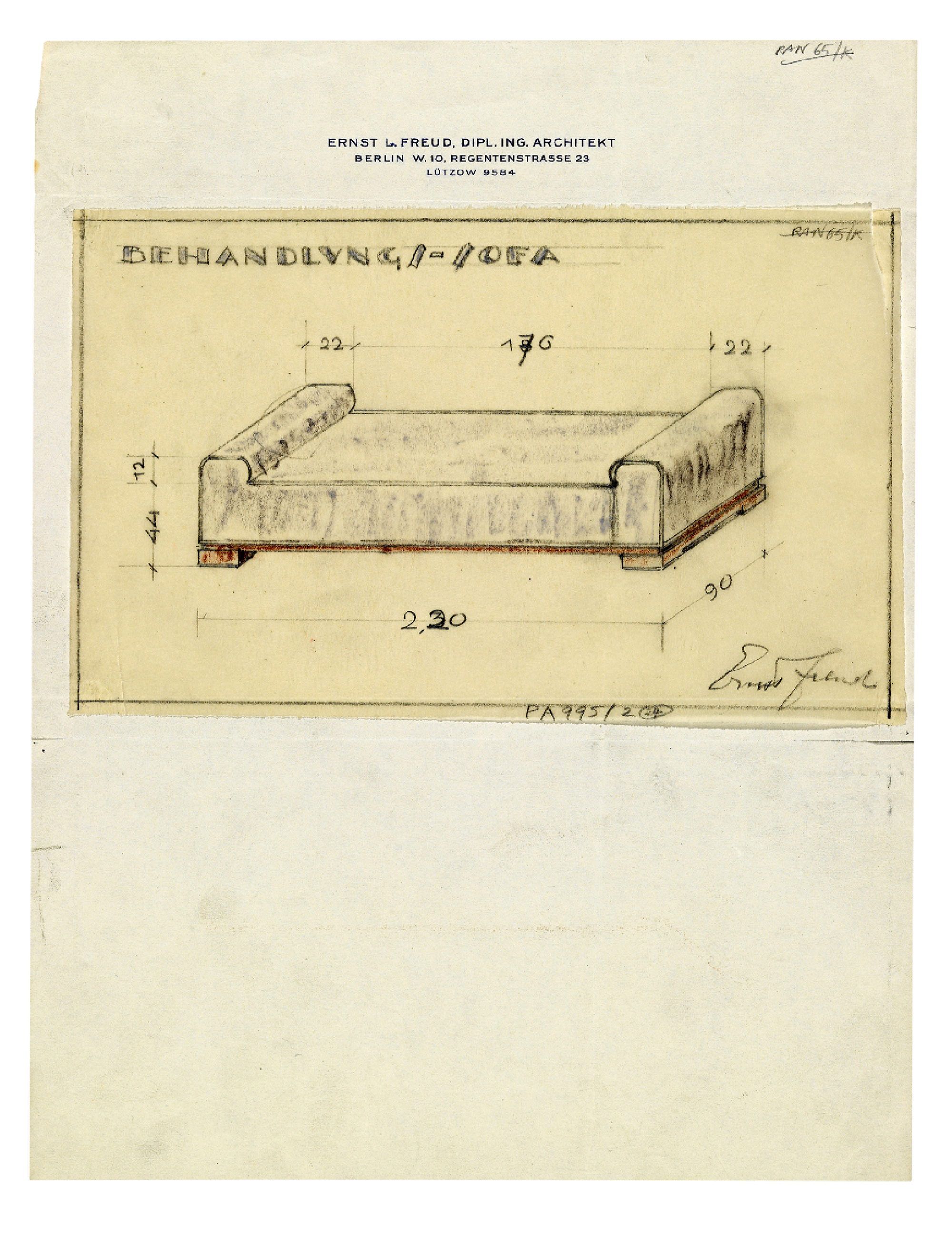

The couch Freud designed for Tegel sanatorium followed the Viennese original while modernizing and abstracting it. It was 220 centimeters long, 52 centimeters tall at the foot end, and 80 centimeters tall at the other. The head end bent steeply upwards, recalling the very high head end of the original couch in Vienna. Two hinges underneath a cylindrical footrest indicate that the vertical end board could be lifted, perhaps to access storage space. Freud’s drawing of the couch does not indicate colors and material other than that the base was to be covered with linoleum. A bulky chair, another Freud design, accompanied the couch. Two square frames made from wood form the sides and armrests of the chair with a thickly cushioned seat in between. The upholstered backrest inclines slightly backwards. Underneath the seat, a pullout footrest recalls a similar feature in the basket chairs that were (and still are) popular at German beaches along the Baltic Sea. Freud would have been familiar with such chairs as he owned a holiday home on the island of Hiddensee.

The setting in the Tegel sanatorium is the only one known to us in which Freud designed a couch and a chair that were made-to-measure for psychoanalysis. Neither piece of furniture has survived, even though we know that another type of couch from the sanatorium made its way to England when its owner, Eva Rosenfeld, a Berlin-born psychoanalyst who had worked at Tegel, fled Germany. When Simmel’s sanatorium folded in late 1931, Rosenfeld received a couch in lieu of her final salary. It was, however, not the treatment couch depicted in the photographs, but a daybed used in the sanatorium, which, once in England, was put to use as a consulting couch. Covered in green rep, it was flat and rectangular, remarkably like the consulting couches Freud designed for settings other than Tegel.[10] In fact, Tegel aside, his drawings for couches—whether for therapeutic or domestic settings—usually showed low, rectangular pieces of furniture with cylindrical armrests at one or both ends. Depending on the intended use, the drawings were simply labeled “couch” or “treatment couch,” thus illustrating a pragmatism that allowed his designs to do double-duty in varied environments.

In 1933, after Ernst Freud had fled to London, Melanie Klein asked him to refurbish her house and consulting room in St. John’s Wood. Freud divided an L-shaped drawing room into a smaller waiting room and a consulting-cum-living room. The latter was furnished with bulky armchairs, a sofa, various Freud-designed tables, and a couch that, again, was quite similar to ones he had designed for private homes in Berlin. The couch stood next to the single armchair visible at the right edge of a photograph of the room (as is still the case, analysts were often reluctant to have their couches photographed, which might explain the way in which the framing of the image omits this crucial piece of furniture). Some time before she passed away, Klein gave the chair and the couch to the American psychoanalyst Donald Meltzer, who had come to London in 1954 and who was still using both pieces when I interviewed him in Oxford in 2002. The couch had two wooden armrests inset with a double layer of cane. It was upholstered with pale green, narrowly striped rep; the original fabric still covered the couch in 2002. Cylindrical cushions from the same material could be used as back support if the couch was placed alongside a wall. The fate of both pieces after Meltzer passed away in 2004 is unknown.[11]

In London, Freud could finally also design a consulting room for his father. In 1923, in his architectural youth, Freud had longed to reorganize Berggasse 19 along more functional principles, a wish that at the time had provoked a sharp rebuttal from Anna Freud. Fifteen years later, as a mature architect Freud suddenly not only had the opportunity but the responsibility to create a new home for his parents, including the last consulting room his father would ever use.

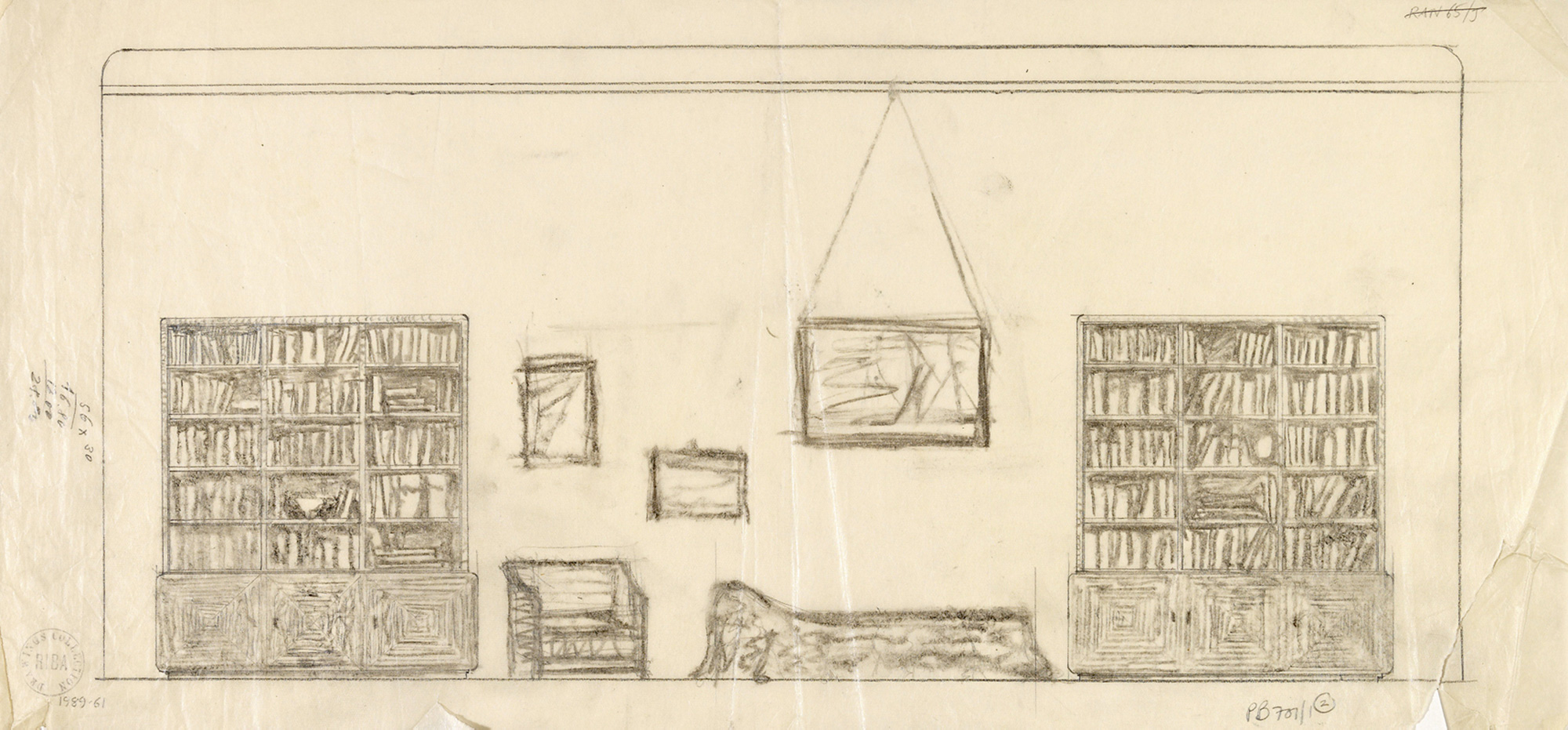

A few months after their arrival in exile in London in 1938, Sigmund and Martha Freud moved into their last home, located at 20 Maresfield Gardens in Hampstead. By then, the house had been extensively remodeled; one goal was to recreate the interior of Sigmund Freud’s Viennese study and consulting room, which together with the couch and the adjacent chair, had come to symbolize both psychoanalysis and the life of its founder. Any accurate and detailed recreation of the spatial arrangements of the Viennese rooms in London was impossible as the study and consulting room were now combined into a single space. Initially, Ernst bracketed the couch with bookshelves, assuming a surviving sketch that shows a couch with a tall head end was indeed for his father’s London home. The rescue, however, of many personal possessions, furniture, and Sigmund’s beloved collection of antique statues and stone carvings provided a sufficient number of familiar objects to recreate the atmosphere and the visual impression of the Viennese rooms. Along one wall, Ernst provided a floor-to-ceiling bookshelf that accommodated the books the older Freud had valued enough to have shipped to London. Integrated into the new shelf were two Biedermeier display cabinets that in Vienna had held parts of the antiquities collection. More antiquities were placed on a rustic table in front of the shelf and in other display cabinets distributed throughout the room. Against another wall, the couch was placed with the armchair standing perpendicular to the head end. Above the couch, some of Sigmund’s art prints were hung, and behind it a rug covered the wall. In front of the couch was a desk and a chair, the latter of which had been designed in 1930 by Felix Augenfeld—Ernst’s friend from their days as architecture students in Vienna—as a gift from Anna Freud to her father.

The ensemble was reminiscent of that in Vienna, yet it was not an accurate recreation. For example, the Abu Simbel print that hung above the couch in Vienna was now above a fireplace. The room appeared as if it had been recreated from memory by arranging the most important objects close to where they had been placed in the Vienna rooms. Considering that the couch and chair form the essential site of psychoanalysis, the London consulting room-cum-study is an example of the transferability of this intimate spatial setting into different architectural spaces.

At the same time, the orderly hand of Ernst Freud was visible in small design adjustments like, for example, the near-symmetric integration of the display cases into the bookshelf or the lightly toned walls that made smaller groupings of furniture and objects stand out much more than in the darker spaces of the Berggasse apartment. These clusters created deliberate reference points of familiar objects in the still unfamiliar surroundings of the new home—both in the sense of a Zuhause, the physical setting in a house, and a Heimat in London and England. Sigmund Freud was aware of these subtle, but fundamental changes in the display of his art collection. In a letter to fellow analyst Jeanne Lampl de Groot—written on 8 October 1938, only days after moving into his new home—Freud commented that his collection of statues and antiquities were now more visible than they had been before. He continued that his collection was no longer a living one, for he could no longer add new pieces to it.[12] Thus close to the end of his life, it was his collection of antiquities that was more on the analyst’s mind than the setting of couch and chair, the symbols of his profession, or even their architectural surroundings. What might appear to be neglect of his son’s work could be interpreted, however, as an indirect compliment of Ernst Freud, who had strived throughout his professional life to practice architecture that would not impose itself on his clients; quite comparable to his father’s role in the psychoanalytic process.

The author wishes to thank Berghahn Books for their kind permission to draw on material from his book Ernst L. Freud, Architect: The Case of the Modern Bourgeois Home (Oxford & New York, 2012).

- Pryns Hopkins, Both Hands before the Fire (Penobscot, ME: Traversity Press, 1962), p. 94.

- Michael Schröter, ed., Sigmund Freud, Max Eitingon, Briefwechsel 1906–1939 (Tübingen: Edition Diskord, 2004), vol. 1, letter 161E. My translation.

- Ernst Falzeder, ed., The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Karl Abraham 1907–1925, trans. Caroline Schwarzacher (London: Karnac, 2002), letter 317A.

- Clarence Paul Oberndorf, “The Berlin Psychoanalytic Policlinic,” The Psychoanalytic Review, vol. 13 (1926), p. 318.

- All the following details are from documents in the private archive of Schloss Tegel, Berlin.

- Neil Bingham, Christopher Nicholson (London: Academy Editions, 1996), p. 72; Jack Pritchard, View from a Long Chair: The Memoirs of Jack Pritchard (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984), p. 114.

- Pearl King, ed., No Ordinary Psychoanalyst: The Exceptional Contributions of John Rickman (London: Karnac, 2003), p. 61.

- Joseph D. Lichtenberg, “Forty-five Years of Psychoanalytic Experiences on, behind, and without the Couch,” Psychoanalytic Inquiry, vol. 15, no. 3 (1995), p. 284.

- Trygve Braatøy, Fundamentals of Psychoanalytic Technique (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1954), p. 111.

- The couch was described in a letter to the author from Victor Ross, son of Eva Rosenfeld, dated 30 July 2002.

- Attempts to contact the Donald Meltzer Psychoanalytic Atelier (www.psa-atelier.org) and the Donald Meltzer Development Fund have been unsuccessful.

- SF/K to N, box 17, Sigmund Freud Museum, London.

Volker M. Welter teaches architectural history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is the author of Biopolis: Patrick Geddes and the City of Life (MIT Press, 2002) and of Ernst L. Freud, Architect: The Case of the Modern Bourgeois Home (Berghahn Books, 2012). His current book project, titled “Tremaine Houses: Patronage of Mid-Twentieth-Century Modern Architecture in the US,” focuses on American bourgeois domestic architecture.