Inventory / The Tokens

Orphaned at the Foundling Hospital

Christopher Turner

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

When the London Foundling Hospital, established “for the maintenance and education of exposed and deserted young children,” opened on 25 March 1741, a crowd of women with their unwanted babies queued outside. At 8 o’clock in the evening, to preserve the anonymity of these guests, the porter put out the lights over the entrance and let the ladies in one by one. The first thirty women whose offspring were deemed healthy enough were relieved of their swaddled bundles.

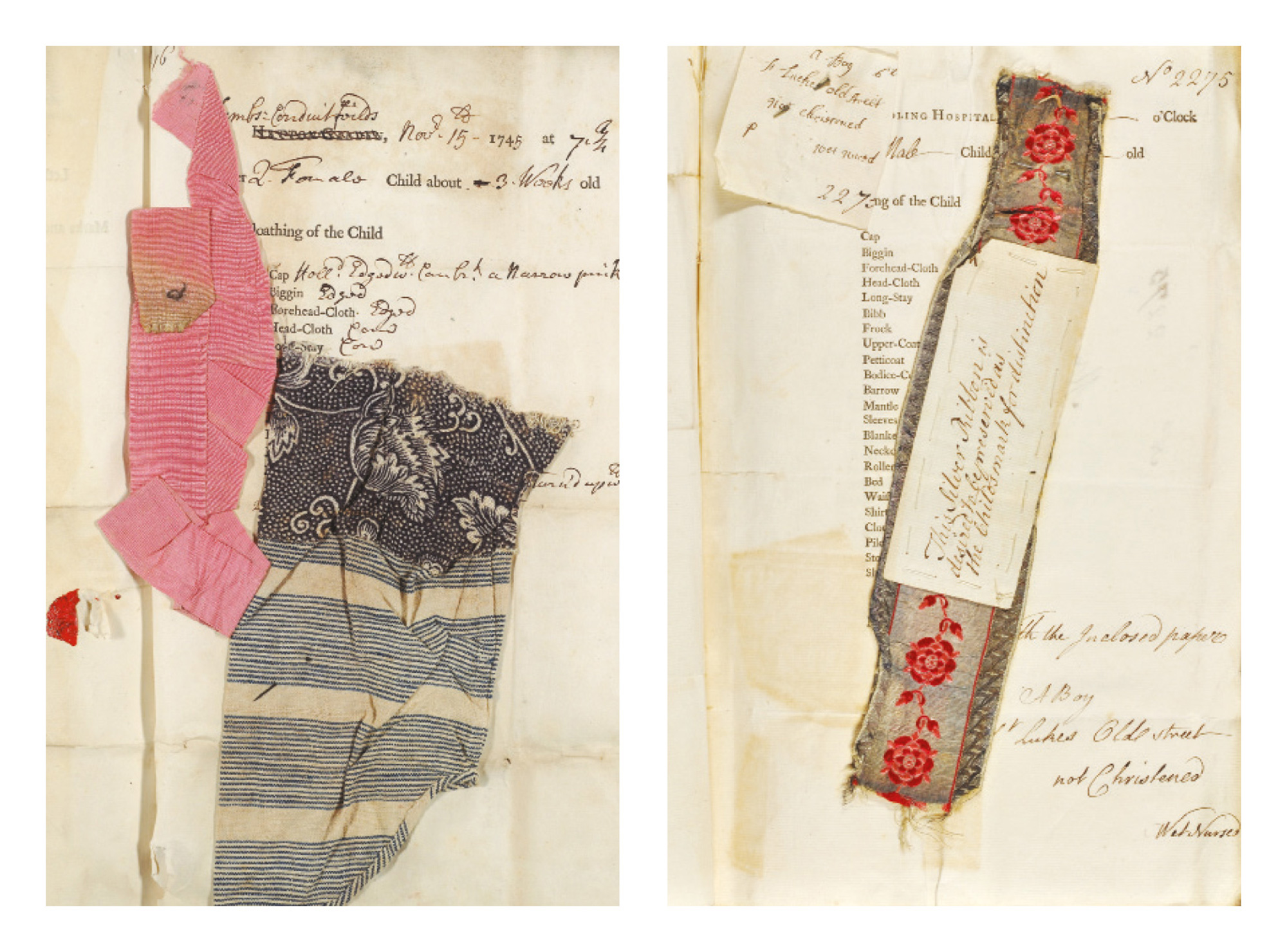

Each baby was numbered and a registration form, or “billet,” listing its sex, age, and what it was wearing was completed; their admittance number was then stamped on a lead tag and placed around their necks. The orphans (all aged two months or less) were baptized and renamed, and were then sent to wet-nurses outside the city with whom they stayed until they were five. Infant mortality rates were high in eighteenth-century London: of this initial intake of infants, many of whom “appeared as if Stupefied with Opiate, and some of them almost starved,” several died within days, and twenty-three within the first few months. Wet-nurses were given a generous annual bonus for keeping their charges alive.

The following year, to prevent “disorderly scenes” and to ensure fairness, a lottery system was introduced. In the hospital’s grand Court Room, watched by the wealthy society ladies and their husbands who governed and funded the charitable institution (including William Hogarth and George Frideric Handel), those bringing children were invited to pick a ball from a bag. If they selected a black ball, they were escorted immediately from the premises; a white ball meant that the child was admitted, on the condition that they passed a medical examination; a red ball meant that if any of those offered a place failed this exam, the child had another chance at the lottery. Annual admission never exceeded two hundred, and three-quarters were turned away. By 1756, 1,500 children had been welcomed. Two-thirds of those died.

That year, the government extended financial help to the hospital on the condition that all children were accepted. During “the great reception,” as it was known, infants could be left in a basket at the hospital gates. Annual admissions exploded and fifteen thousand infants, from all over England and Wales, were admitted during the four years of the scheme. When the government program was discontinued after accusations that it encouraged vice and illegitimacy, children were admitted by written petition only in letters that usually named the mother. In rare cases, anonymity was guaranteed (for the illegitimate children of the upper classes) with a donation of one hundred pounds.