Strategic Arborealism

Hidden in plain sight

Jonathan Allen

During his childhood visits to the Habsburg palace of Schönbrunn in Vienna, the young Franz Ferdinand would no doubt have explored the fantastical rooms created in 1769 by the Bohemian baroque painter Johann Wenzel Bergl for the aging sovereign Maria Theresa of Austria. Within the four interlocking garden chambers of the palace of his uncle—the Austro-Hungarian emperor Franz Joseph—elaborate trompe l’oeil landscapes and themed faience wood-burning stoves bear witness to Habsburg cultural voracity and exotic tastes. One of the stoves takes the form of a gilded tree, a lumpen mandrake-like structure perched on leafy feet and curling upward toward a loop of branches within whose twiggy embrace a bird feeds its nested young. Perhaps the future heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne warmed his hands on Bergl’s tree, charmed by its sentimental depiction of vulnerable youth, and ignorant of the labor of servants stoking the hearth from behind with logs via a network of service corridors hidden within the palace walls. Had Franz Joseph laid his hand on the same tree in late July 1914—after his nephew’s assassination in Sarajevo—when his signed ultimatum to Serbia would precipitate World War I, his palm would have met cold terracotta. Midsummer in Vienna can be uncomfortably hot, and the palace’s heating would not have been in use.

The contrast between the palatial luxury of Schönbrunn and the rooms of the Cliffe Hydro Hotel in the North Devon coastal town of Ilfracombe could not be greater. Yet here on 30 November 1918, just a few weeks following the armistice between the Allies and Germany, the convalescing British artist and camoufleur Leon Underwood (1890–1975) could be found sketching the image of an equally fanciful tree, and reflecting upon the machinations of the war that had been sanctioned by Franz Joseph four years previously.

Underwood’s drawing accompanied a letter to Alfred Yockney, a former Art Journal editor who acted as the artist’s liaison with the newly founded Imperial War Museum. The sketch entitled “Erection of a Camouflage Tree in support line Trenches—the hurry before dawn” proposed a painting later commissioned by the museum and completed in September 1919. The artist’s choice of subject—the hollow armor-plated trees erected covertly on the battlefields of northern Europe as observation posts, or “OPs”—documents a unique development in the history of military technology. The canvas shows nine soldiers undertaking various fabricating tasks while a uniformed officer stands surveying the rising morning light. On closer examination, the faces and musculature of each soldier (apart from one) closely resemble one another, an apparent duplication resulting from Underwood’s thrifty re-conscription of his brother and fellow combatant, Horace, to pose for each figure. Underwood’s letter to Yockney ends with a dreadful pun, recommending the planned canvas as representative of pioneering work in the war’s “more technical branches.”

At the outbreak of World War I, military camouflage was a fledgling art.[1] The incentive for its development came mainly from above: the urgent need to protect ground forces from the new threat of aerial attack and reconnaissance. The acknowledged moving spirit within this emerging field was the Parisian portrait painter Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola (1871–1950) who established history’s first military camouflage unit at Amiens in February 1915. Here Scévola took charge of a motley team comprising mainly scene painters, set designers, and artists, all of whom worked alongside military regulars. A British camouflage unit along the same lines soon followed under the charge of Captain Francis Wyatt with the assistance of Solomon J. Solomon, a fifty-four-year-old academic painter given the temporary military rank of lieutenant colonel and tasked with assembling a team of similarly diverse creative professionals. Solomon went on to direct the camouflage training school created temporarily during the war within a fenced-off section of Kensington Gardens, London, while the “Special Works Park” (the covert name adopted by the British Camouflage Section) was established at Wimereux, France, in March 1916.

The contrasting worlds of professional soldiery and artistic production generated logistical conflicts as well as definitional issues. As Lieutenant Colonel George Henry Addison noted in an official postwar compilation of the activities of the British Royal Engineers, “The word Camouflage, associated as it is with dead horses, or pantomime, and savouring therefore of mystery and special technique, led, often unconsciously, to the adoption of an apathetic or non-serious attitude towards camoufleurs. However, the word has arrived with every appearance of making a long stay.”[2] The word camouflage derives from the French verb camoufler, meaning to veil or disguise, or, according to historian Guy Hartcup, “to make up for the stage.” Addison’s reference to “dead horses” may relate to the infamous Trojan horse, but is more likely a reference to an early French observation post which took the form of what appeared (to the enemy) to be the corpse of a horse but was in fact a dummy containing a human observer within its hollow body. Elsewhere, Addison records other vaudevillian details, as can be seen from an instruction label attached to a mass-produced portable machine gun screen that warns its user: “There is no magic in this cover. You must use local material, such as grass, weeds, twigs, earth, rubbish, as the case may be, or else you’ll be SPOTTED easily.”[3] Camouflage units would remain active throughout World War I across the Western Front, with both artists and military authorities gradually shaping this new language of contingent guile.

Camouflaged OP trees evolved specifically as a response to the static nature of fighting on the Western Front and to its resulting denuded landscapes, depicted by artists such as Paul Nash and C. R. W. Newinson. As soldiers sheltered in trenches below ground level, strategists on both sides realized that the legions of blast-shattered trees above might be repurposed for strategic ends.[4] Trees beyond the range of fire were commonly used as sites for telescopic observation, but a hollowed-out, armored-plated structure located directly on the front line might permit the scrutiny of enemy positions at critically close range. The production of covert observation trees seems to have been some of the earliest work carried out by Scévola’s Service de Camouflage, with the first recorded example installed near Lihons in May 1915.[5] The first British OP tree was bolted into position near Bridge 4 on the canal north of Ypres on 11 March 1916, with its design, construction, and installation overseen by Solomon himself. This example distinguished itself by royal association since its outer bark was sourced from a willow in Windsor Great Park with the personal permission of King George V.[6] Prior to this regal artifice, British observers had had some field experience using French OPs, one example of which can seen in a painting by Major Tom Alban at the Royal Engineers Museum in Gillingham, Kent. Alban’s watercolor shows a tree originally installed in January 1916 on the edges of Gommecourt Wood near the village of Hebuterne. By March 1919, however, the structure was a ruin, its bark vestments discarded and decomposing in a newly liberated meadow rapidly re-colonizing under the spring light. The postbellum quietude of this scene could not be more different to the mudded nocturnal urgency of Solomon’s pastel drawing Our First O.P. Tree (1917), in which Royal Engineers can be seen struggling to raise Solomon’s hefty tree by hand under the cover of darkness while the artist shines a torch at its base to locate its securing bolts.[7]

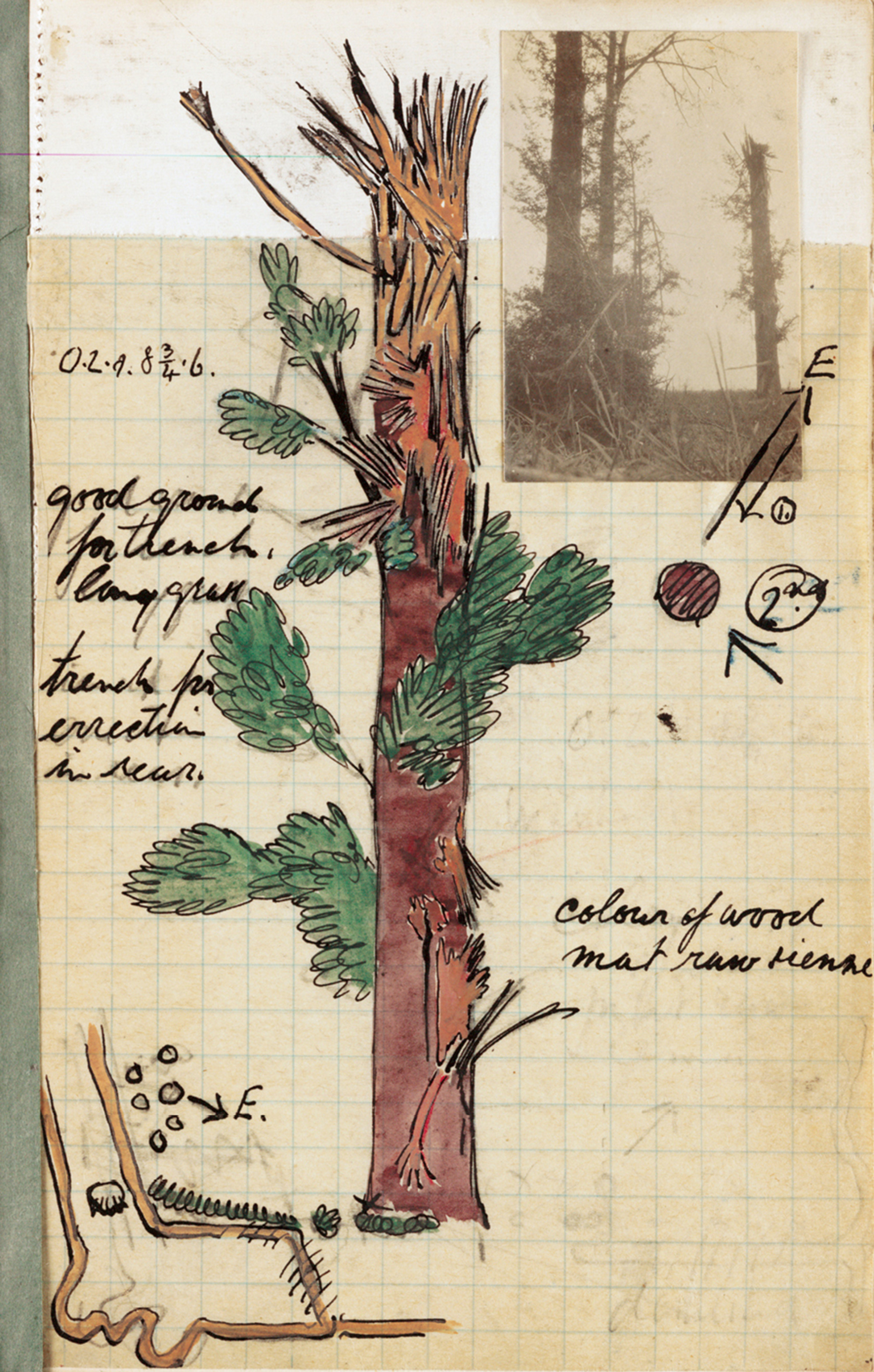

To avoid detection, OP trees had to be indistinguishable from the specimens they were intended to replace, requiring a meticulous process of sculptural mimesis and covert installation. This process began on the page. Once the position of a particular tree had been identified as strategically advantageous, an accurate record of the enemy viewpoint upon it was required, and to capture this hidden elevation, camouflage officers such as Leon Underwood were expected to crawl into no-man’s land at dawn, turn around, and sketch, sometimes just yards from enemy lines. Underwood’s wartime notebook at the Imperial War Museum is filled with such drawings, each annotated with measurements and visual minutiae that could only have been observed through such hazardous proximity—the blast angles of broken branches, variations in bark coloration, and the embedded positions of stray bullets. Many of the artist’s sketches seem to have been glued into his notebook from another source with their latterly applied black ink clarifying pencil lines that were perhaps originally drawn at great speed and considerable personal risk. Like those of his friend and fellow camoufleur, the French Cubist painter André Mare, whose similar notebooks can be found in the Abbaye d’Ardenne in Caen, Underwood’s tender autopsies resuscitate their subjects almost one hundred years after their fatally damaged bodies vanished beneath the mud.

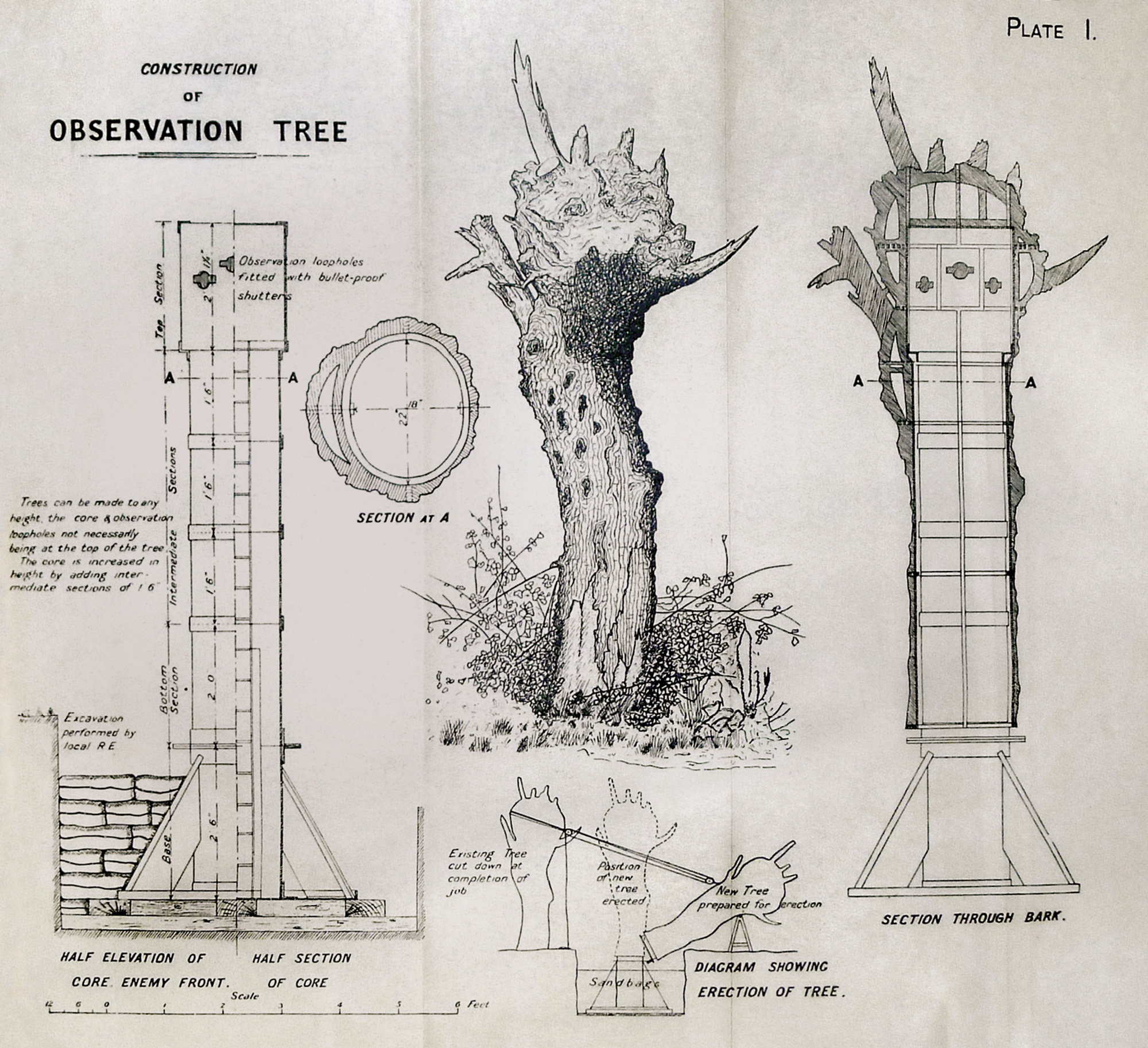

In his description of the next stage of production, Underwood’s letters make reference to “large scale drawings [used] in constructing a replica in colours & form of the original tree.” Addison makes tantalizing reference to the construction of small plaster models “finished in every respect, to enable the copy to be made in the workshops at the Base without the actual presence of the reconnoitring officer.”[8] Although none of these drawings or models appears to have survived, one can imagine their importance as transitional objects between the reconnaissance sketches generated by officers such as Underwood and the towering structures that would eventually be spirited to the front line. One photograph depicts an interior where three uniformed British Royal Engineers stand dwarfed alongside a half-assembled OP tree with two crowns of fictitious blast-shattered wood awaiting completion and final positioning, along with whatever additional branches and encrustations might be required to match the structure with its soon-to-be-felled twin on the front. Although the precise location of this photograph cannot be confirmed, the tree’s pinned, hammered-steel sheeting and bolted upright T’s suggest (by comparing it to Addison’s report) that the photograph depicts the group visiting a French factory before July 1916. After this date, the Special Works Park began to assemble trees using a different system based on the sixty uniform armor-plated steel tubes ordered from Messrs. Roneo of Holborn, London, and around which all subsequent British OP trees were grafted.[9]

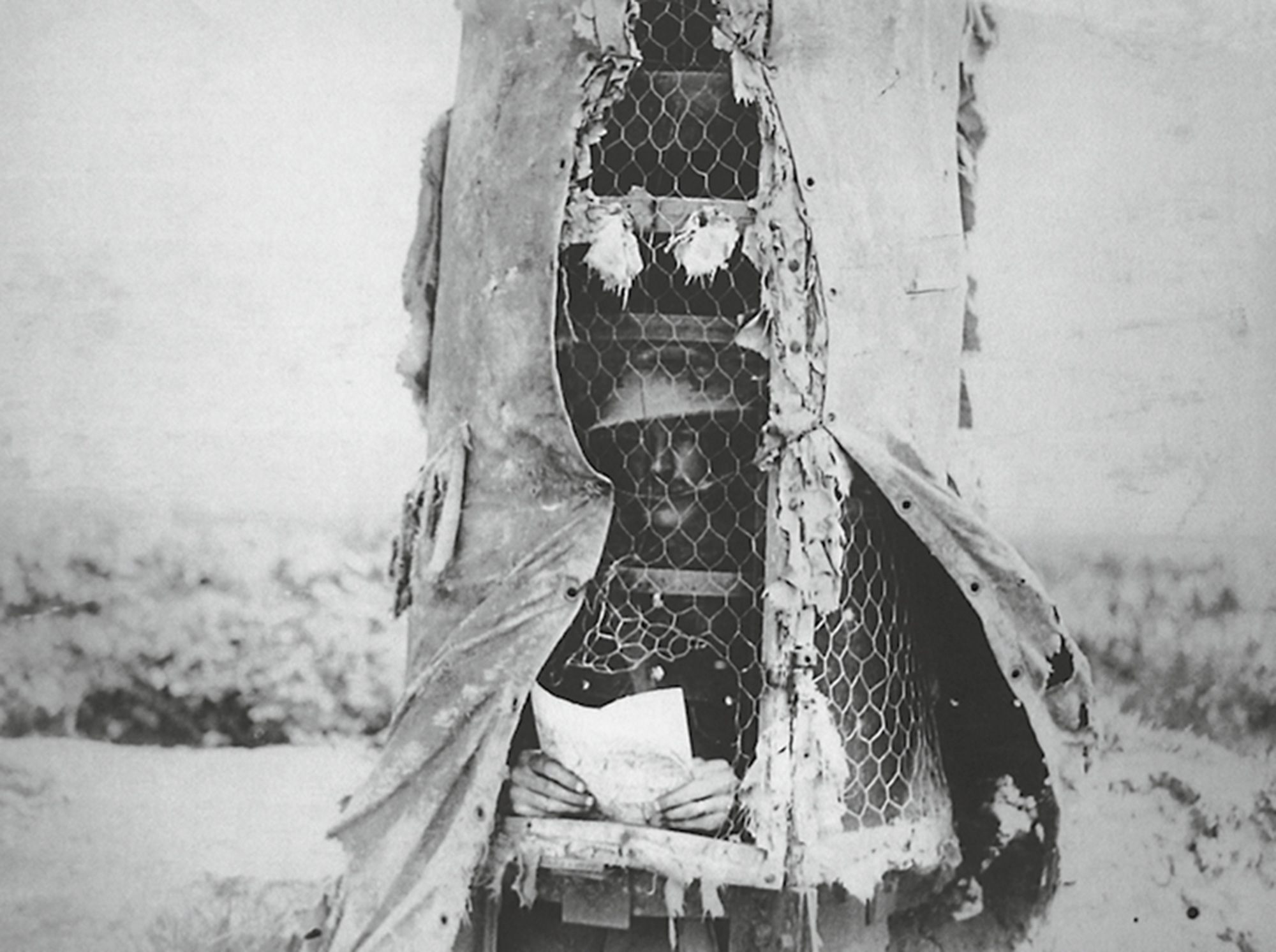

Records differ regarding the fabrication of the naturalistic cladding for these metal cores, with variations perhaps bearing witness to evolving techniques during the war, the various levels of verisimilitude required for specific contexts, and even the skills and tastes of individual artificers. Some reports state that “external appearances [were] faithfully copied in suitable material (thin sheet iron or reinforced plaster),” while other photographs show eyeleted painted canvas laced with twists of ragged camouflage material and pulled taut over a chicken-wire sub-frame.[10] Whatever the techniques involved, it seems reasonable to assume that those within the Special Works Park with scenographic expertise, such as stage designer L. D. Symington or scenery painter Roland Harker, to name just two, were now called upon to complete the tree’s illusionistic detailing. For these West End theater professionals, the creation of fictitious arbors might have felt strangely familiar, and it is tempting to speculate whether workshop conversations ever turned to Birnam Wood, the “moving grove” in Shakespeare’s Macbeth and probably the most celebrated use of strategic arborealism in history. Perhaps Underwood was influenced in some way by this group of displaced thespians, for while recuperating a few years later in Ilfracombe and considering his painting for the Imperial War Museum, he spontaneously penned a ballet, entitled Rickets, a production later danced by an amateur company, according to his biographer Christopher Neve, at Barnstaple Theatre in Devon.

On completion, the tree would be dismantled, loaded onto a truck, and driven to the front to be met by what Underwood describes as a “camping party”—a dedicated team of Royal Engineer sappers. The artist’s painting now provides a clear record of the installation process, especially when read alongside the engineering schematics that appear in Addison’s report in 1926. In both visual documents, for example, one can discern the hollow circular steel base, against the top edge of which the re-assembled tree would pivot, then to be hauled up from wooden trestles using a system of ropes, one of which can be seen dangling directly to the right of Underwood’s upright tree. The sandbags being filled by the two kneeling figures to the right side of the painting would provide ballast around the steel base to prevent the rootless tree from toppling. One of these figures might be a commemorative portrait of Solomon J. Solomon, whose features in profile closely resemble a self-portrait by the artist in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Underwood describes the final steps in his correspondence to Yockney: “The first opportunity offered by low visibility or, failing that, the cover of night was taken to haul up and bolt down the ‘Camouflage Tree’ [and] cut down and bury the original.” A large crosscut saw on the left of the painting stands poised to facilitate this final act of concealment. Underwood’s scene is unfolding in daylight because his painting recollects a particular installation when “the distance to the enemy’s position was great enough to obviate the more stringent precautions against detection that were employed in other cases … The trees erected in the Lines of Defence were done but not without exception, in the day time.” Yockney’s aesthetic directives may also have played a part in Underwood’s choice of daylight: “For style I would like you to bear in mind the necessity of propaganda, and for this reason the design should be within the grasp of the public rather than a purely aesthetic composition.”[11] Underwood had been known to embellish his military fieldwork with modernist flourishes in the style of F. T. Marinetti and Wyndham Lewis, and perhaps Yockney also had in mind Solomon’s lugubrious pastel of the same subject of two years earlier. Underwood’s response was a canvas blocked out in bold contoured color that evokes socialist realist tableaux with their unfolding narrative readability, didactic themes of solidarity through struggle, and celebration of heroic stripped-down bodies wresting nature’s latent potential for instrumental ends.

Despite its regal cladding, Solomon’s first observation tree near Ypres proved an almost unmitigated failure due to its poor strategic positioning, limited height (at just eight feet tall), and restrictive internal width. According to Addison, the tree was “too small to admit any but a most determined and enthusiastic man … On the whole it can not be said that O.P. trees proved a great success.”[12] The lack of observer comfort seems to have been one determining factor in the ineffectiveness of this experimental technology. Productive covert observation can require long stints of concentrated immobility, and so the physical and psychological well-being of the observer becomes a crucial design consideration. OP tree observers might be perched for hours on a tiny metal platform within a highly restrictive space—an oven in summer and refrigerator in winter—from which they viewed the field through bulletproof shutters with restricted sightlines, talking notes or making sketches under low artificial light. This homuncular existence might have been supplemented from time to time by the unhappy spectacle of machine-gun fire tearing through the bodies of friends on the battlefield below, horrors from which the observer was himself, almost certainly guiltily, insulated.

The physical discomfort and potentially disturbed inner life of the OP tree observer would have been of less interest to those further up the strategic hierarchy than the relative usefulness of the information gleaned from such observation positions. Many British OPs also failed in this regard because, as Addison notes, the “trees selected did not always give observation that was absolutely vital and which could not be obtained from somewhere else.” Furthermore, blame could not be “laid to the account of reconnoitring officers, who neither knew the front, nor the artillery needs.”[13] More effective observation information could often be gathered by mobile and responsive observers on the ground such as Paul Maze, Adrian Hill, and Sydney Jones, who, as historian and artist Paul Gough notes, were just the latest in a long tradition of artists whose reconnaissance drawing and panoramas enabled a more complete “calibrating of the battlefield.”[14] The description of terrain at far larger scales increased in accuracy throughout the war following the impact of aerial photography on mapmaking. Another historian and artist, Peter Chasseaud, has assembled definitive histories of these augmented cartographies and, reflecting on the landscapes of Paul Nash, notes that the “cartographers of the field survey companies provided an altogether more objective, if not unpoetic, map of the same landscape.”[15] Information drawn from OP trees would have contributed, therefore, in some small way to an overall refinement and harmonization of represented space within the theater of war during World War I. Given that German OP trees were discovered dotted across the Western Front following the Allied victory, it seems that the same endeavor took place on both sides of the trenches, and it is not inconceivable, therefore, that observers, cartographers, and even artists like Nash inadvertently absorbed enemy OP trees within their various visual records of the front.

Read cartographically, Addison’s schematic diagrams and Underwood’s letters together reveal that the landscape depicted in the painting Erecting a Camouflage Tree must have been a view looking westward, toward Allied occupied territory and, more importantly for Underwood, toward home. The artist’s subsequent oeuvre following the war was informed in large part by his travels in Iceland, Mexico, and elsewhere, excursions which filled the canvases on his studio walls in London with arcadian vistas, exotic plant life, and the kind of creaturely vitality that can be found in Bergl’s rooms in Vienna. Yet Underwood’s wartime notebook holds one final surprise. Glued inside its front cover, a photographic portrait shows the artist wearing a trench coat and standard-issue Brodie helmet, and standing beside a fellow officer. His gloved right hand carries what appears to be a white stick, and on the same hand, held out in the manner of a falconer, perches a bird.[16] But this creature is not the kind of aristocratic raptor that would have been found within Schönbrunn’s famous royal menagerie, nor one of the vividly plumed genera of his trip to Mexico. Instead, it’s a bird altogether more appropriate as a companion for a cunning practitioner of the arts of Special Works Park—perhaps even its avian mascot—a creature known worldwide for its intelligence and productive deceptiveness, as well as its beauty. And that bird? The common Eurasian magpie.

- One of the earliest documented examples of systematic military camouflage involved the deliberate planting of trees on the British south coast to hide ordnance from the threat of artillery attack from vessels at sea. A memorandum from Andrew Clarke, Inspector General of Fortifications, reads: “H.R.H the F.M. Commanding-in-chief directs the immediate attention of C.R.E’s to the desirability, in a large number of cases, of planting suitable trees, shrubs and plants on existing works of defence … The objects to be obtained are various:- 1. A mask outside a work hiding guns from fire to which they are unable to reply … 2. The concealment of the general features of a work or battery … 3. An obstacle to attack.” This directive outlines some of the optical theories of camouflage later developed by Abbott H. Thayer. See “Memorandum for Commanding Royal Engineers” from the War Office on 30 April 1884, The Royal Engineers Journal, vol. 14 (London: Spottiswoode & Co., 1884); Tim Newark and Jonathan Miller, Camouflage (London: Thames & Hudson, 2007); and Hanna Rose Shell, Hide and Seek: Camouflage, Photography, and the Media of Reconnaissance (New York: Zone Books, 2012).

- George Henry Addison, The Work of the R.E. in the European War, 1914–18 Miscellaneous (Chatham: W. & J. Mackay & Co. Ltd., 1926), p. 112.

- Ibid., p. 133.

- In addition to the forty-five OP trees erected by the British Royal Engineers during World War I, a number of “periscope trees” were also constructed. An existing tree was replaced with an armor-plated duplicate within which a sophisticated periscope system had been installed. The periscope would be manned via a subterranean tunnel system, allowing “indirect observation” of enemy positions. Another common strategic use of trees in the same context involved the removal or relocation of living specimens in order to confuse the targeting systems of enemy artillery and machine guns (i.e., to disrupt the datum points and zero lines entered into a battery’s “artillery board”).

- In Camouflage: A History of Concealment and Deception in War (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1979), military historian Guy Hartcup notes that French OP tree observers were connected by telephone to command positions in the trenches behind them.

- Nicholas Rankin, Churchill’s Wizards: The British Genius for Deception, 1914–1945 (London: Faber & Faber, 2008) On pages 81–82, Rankin examines the relevant written correspondence regarding Solomon’s sequestration of quantities of royal bark.

- Solomon’s pastel Our First O.P. Tree (1917) was exhibited at the Royal Academy in October 1919 as part of the “Exhibition of Works by Camoufleur Artist with Examples of Camouflage.” Both Leon Underwood and Tom Alban presented work, although neither exhibited their already completed paintings of camouflage OP trees, despite, in Underwood’s case, a clear desire to do so, as recorded in a letter to Yockney on 9 September 1919.

- Addison, The Work of the R.E., p. 121.

- A tiny photograph glued into Underwood’s notebook almost certainly shows Solomon J. Solomon’s first OP tree (with its recognizable bulbous pollarded crown) being assembled at the British camouflage factory at Wimereux. Solomon designed the tree as an optical illusion whereby, if viewed from the front, the tree would appear far too small to conceal a human body.

- History of the Corps of the Royal Engineers, vol. 5 (Chatham: The Institution of the Royal Engineers, 1955), p. 487.

- All material quoted within this text relating to correspondence between Leon Underwood and Alfred Yockney can be found in file ART/WA2/03/029 at the Imperial War Museum, London. The idiosyncrasies of language and syntax of these original sources have been left intact.

- Addison, The Work of the R.E., p. 122.

- Ibid., p. 123.

- Paul Gough, A Terrible Beauty: War, Art and Imagination, 1914–1918 (Bristol: Sansom & Co., 2009). Gough notes that observation drawing is still often used on the contemporary technologized battlefield. He interviewed Captain Tim Henry, Forward Observation Officer with 266 (GVA) Battery, 7th Royal Horse Artillery, who described the usefulness of observation drawing, especially when technology breaks down, as “fag packet gunnery.” Gough re-describes the latter as “impromptu, rudimentary, but effective.” See pages 89–90. In a different context, a contemporary example of the value of direct observation can be found in the work of the UK anti-nuclear collective NukeWatch. Activist Juliet McBride has climbed the same oak tree for twenty years to observe and monitor the departure of convoys containing nuclear warheads from AWE Burghfield. The convoys travel for hundreds of miles using the public UK road system, often obstructed by NukeWatch’s activities.

- Peter Chasseaud, Topography of Armageddon: A British Trench Map Atlas of the Western Front, 1914–18 (Lewes: Map Books 1991), p. 7, and Artillery’s Astrologers: A History of British Survey and Mapping on the Western Front, 1914–1918 (Lewes: Map Books, 1999). This article owes a debt of gratitude to Chasseaud, who introduced the author to Lieutenant Colonel George Henry Addison’s Royal Engineers’ report.

- These combined iconographical attributes—a magpie and a white stick—are associated with Saint Oda, a thirteenth-century saint who, following her miraculous recovery from blindness, found herself constantly disturbed by chattering magpies as she prayed in and around the villages of the Netherlands and Belgium. The birds eventually led her to a forest clearing, where now be can be found the village of Sint-Oedenrode.

Jonathan Allen is a visual artist and writer, and currently a researcher in the Hall of Records at the Centre for Useless Splendour, Kingston University, London. For more information, see jonathanallen.info.