Leftovers / The Incorruptibles

Tales from the crypts

Jeffrey Kastner

“Leftovers” is a column that investigates the cultural significance of detritus.

It was the morning of 22 November 1599 and a crush of faithful was pouring into the Trastevere neighborhood of Rome. Their destination was a church not far from the Ponte Cestio, the ancient bridge connecting the Isola Tiberina to the right bank of the city’s winding river. Originally constructed in the fifth century, the Basilica of Santa Cecilia was on that day to be the site of a most sacred ceremony, one presided over by forty-two cardinals, the diplomatic representatives of France, Venice, and Savoy, and Pope Clement VIII himself. So great was the crowd of worshippers that the area was closed to vehicular traffic; as the day went on, the Pontifical Swiss Guard had to be called in to keep order in and around the church.[1]

Catholic tradition recounts that the namesake of the church, Saint Cecilia, had probably been born sometime in the second century into a wealthy, senatorial Roman family. Raised as a Christian, she was married off to a pagan nobleman named Valerianus, but on her wedding night she informed the groom that she was already betrothed to an angel and therefore could not submit to his husbandly advances. Valerianus was eventually swayed by his bride’s faith and converted to Christianity, as did his brother. The two brothers were soon executed for their beliefs, and Cecilia was condemned to death as well, first by suffocation in her overheated bathroom and, then, when that failed, by beheading. Yet when the executioner struck her neck three times with his sword—the maximum number of blows allowed by Roman law—Cecilia did not die. Instead she lingered, mortally wounded but still conscious, on the floor of her bath for three days, disposing her goods to the poor and requesting of her fellow believers that her home be later dedicated as a church. (She also, according to some versions of the legend, spent that time singing hymns of praise to God—she is today the patron saint of musicians.)

Santa Cecilia was supposedly constructed on the site of the martyr’s home in Trastevere, and when Pope Paschal I located her body in a nearby catacomb in the early part of the ninth century, he moved it there and placed it beneath the high altar during work on the building he was overseeing. It was on that site during a subsequent renovation of the basilica that her body was again rediscovered—more than seven hundred years later, on 20 October 1599—by Paolo Emilio Sfondrato, a cardinal who was then the priest of the church. According to the lore surrounding Cecilia, however, it was not simply the fact of her remains being located that caused the prelate to announce the find to Pope Clement VIII, who promptly proclaimed that they be displayed in public for a month before their reinterment on that November day. Indeed, it was asserted that the virgin’s uncorrupted body was miraculously found in the exact position in which she was supposed to have died, bloodstained cloths at her feet, the wound in the flesh of her neck still visible.[2] Her supposed disposition was recorded for posterity in one of the era’s most celebrated sculptures: a marble figure made by Stefano Maderno, which still lies today in a niche in front of the church’s black marble altar. The artist’s contemporaneous inscription, etched in Latin into a round slab set in the church floor, echoes the claim that has come down through history: that Saint Cecilia’s holiness was such that she had managed to elude the fated way of all flesh: “Behold the body of the most holy virgin Cecilia, whom I myself saw lying incorrupt in the tomb. I have in this marble expressed for you the same saint in the very same posture.”[3]

• • •

Despite the longstanding ecclesiastical traditions around the relationship of bodily incorruption and sanctity, the phenomenon of naturally well-preserved ancient cadavers is hardly confined to the realm of Christian belief. Examples abound in contemporary scientific literature: Tollund Man, for example, an Iron Age corpse found with a rope around its neck in a Danish peat bog in 1950, was so unchanged by time that investigators initially believed the 2,500-year-old body was a recent murder victim, while so-called Lady Dai, a nobleman’s wife who died around the time of Christ, had been sufficiently unaffected by two millennia in the ground that when she was disinterred from a family tomb during an archeological dig in China’s Hunan Province in the early 1970s, doctors were able to perform a full physical examination on her, finding both the remnants of her last meal in her stomach and Type A blood in her veins.[4] Accounts of incorrupt secular bodies similarly feature in the broader social and cultural imagination. The discovery of the perfectly preserved body of a young woman in a tomb along the Appian Way in 1485, for example—widely believed at the time to be Tulliola, the daughter of the first-century BCE Roman statesman and orator Cicero—was, according to scholar Leonard Barkan, “leaving aside matters of obvious and immediate political significance … the most fully documented event to take place in Rome during the fifteenth century.”[5]

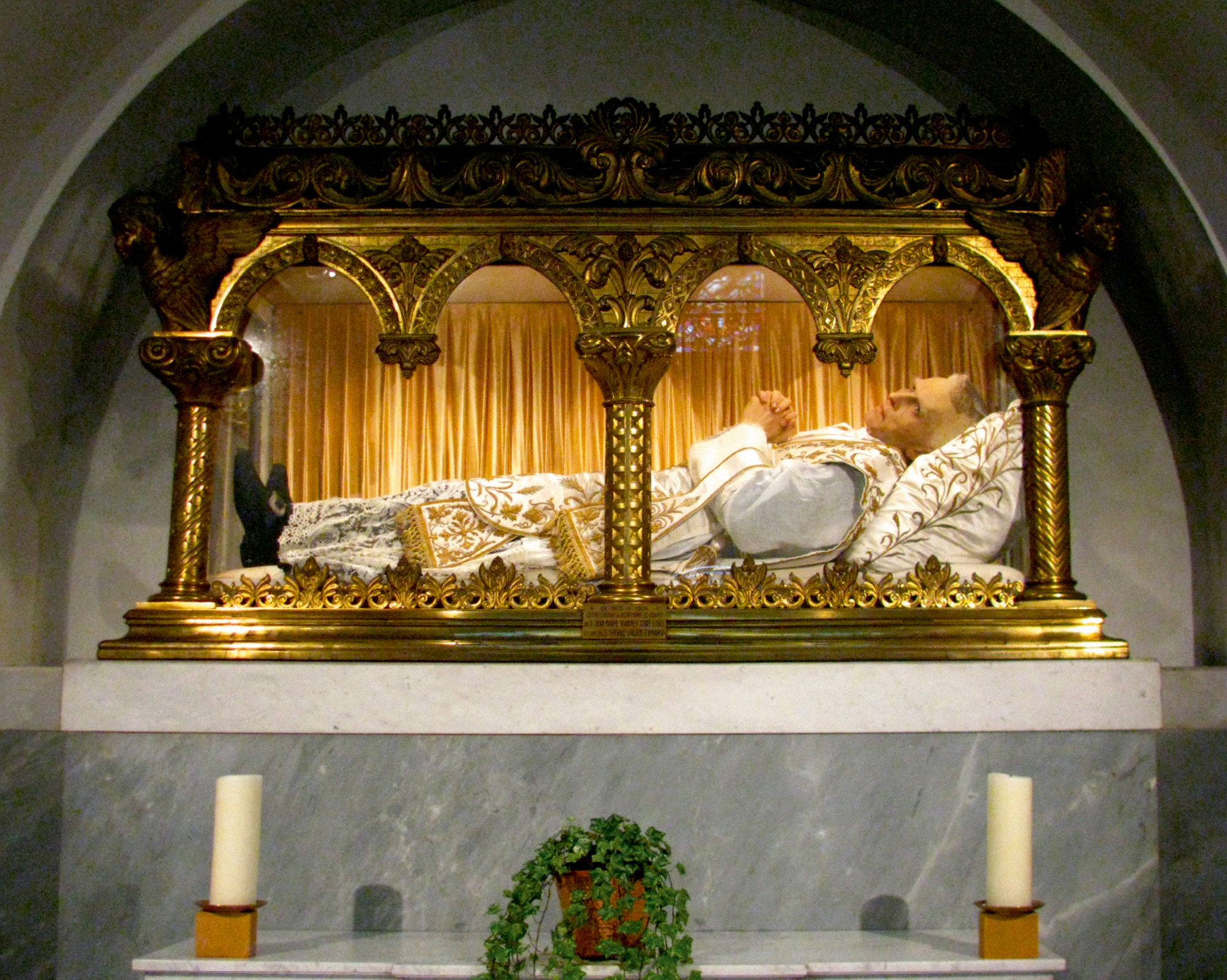

Yet it is within the Catholic Church that physical incorruption has been most closely linked to metaphysical beliefs. Exhumation for the purposes of identification and the recovery of relics has long been a fundamental step in the official process of the church’s election of saints. Indeed, as recently as 2007, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints—the Vatican body responsible for overseeing the processes of canonization—published a document titled “Sanctorum Mater: Instruction for Conducting Diocesan or Eparchial Inquiries in the Causes of Saints,” which detailed contemporary procedures related to the “canonical recognition of mortal remains,” namely the disinterment and examination of candidates for sainthood.[6] The identification and confirmation of miracles performed by these potential saints has been part and parcel of the investigatory process through the centuries, and though as time has passed the church has whittled away the kinds of mystical occurrences that qualify one for sainthood, the image of the body that resists decay—a terrestrial instantiation of the spiritual life everlasting promised by Christian salvation—has remained a potent object of fascination and veneration.

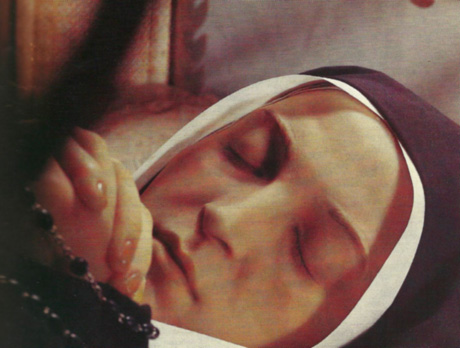

A quick internet search for “incorruptibles” will yield literally thousands of hits with images and accounts of saints and other holy figures whose bodies continue to be venerated for their unsusceptibility to the ravages of time. While a number of churches and shrines continue to promote their hosting of holy bodies, many of the online sites tend to be homemade affairs, and these frequently trace their information back to The Incorrutpibles, a book written in 1977 by Joan Carroll Cruz, a Louisiana housewife and author.[7] Published under the imprimatur of the Archbishop of New Orleans, Cruz’s thoroughgoing study collects the stories of 102 different cases of holy incorruptibility, beginning with Saint Cecilia, who Cruz calls the first saint “whose body experiences the phenomena of incorruption,” and continuing on through saints more famous (Edward the Confessor; Teresa of Avila; Bernadette Soubirous, whose childhood visions of the Virgin Mary turned Lourdes into a worldwide site of pilgrimage) and less, up until the turn of the twentieth century. Though it acknowledges the traditions of embalming and the variety of natural phenomena that might cause the body to decay in unusual ways—environmental factors like temperature, humidity, and soil or water conditions, as well as saponification, a rare condition caused by the formation of adipocere, a waxy substance produced by the breakdown of body fat, which preserves the cadaver’s features with uncanny fidelity—Cruz’s book is very much the work of a true believer and frequently elides contradictions in historical accounts.[8]

A slightly more dispassionate source of information on incorruptibles—and a primary source for Cruz—is The Physical Phenomena of Mysticism, by the Jesuit scholar Herbert Thurston.[9] Relying on numerous original documents, Thurston’s book ranges over the gamut of miraculous wonders from the history of the Catholic Church—from levitation, stigmata, and telekinesis to more obscure marvels including “human salamanders” (those impervious to extreme heat or fire), curious instances of bodily elongation and other ecstatic changes of shape, and holy men and women able to live without eating. It also devotes an extended chapter to incorruption. The nearly forty pages Thurston expends on the phenomenon are peppered with editorial observations that suggest his tendencies, even within a context of deep faith, toward objectivity, even going so far as to write early on in his study: “Of course it must be recognized throughout in dealing with this subject that cases of a remarkable and seemingly unaccountable preservation of human remains are sufficiently common to make it rather difficult to decide in any individual instance that the absence of corruption is due to anything more than mere coincidence.”[10] More intriguing still are Thurston’s gentle attempts to decouple incorruptibility from great sanctity. “There is also the fact,” he observes, “that the occurrence of the phenomenon is extremely arbitrary, and, to judge by human standards, inconsistent. So far as the available evidence allows us to speak positively, there is every reason to believe that this special privilege of incorruption was not accorded to some of the greatest saints who have glorified the Church in the course of the last eight centuries.”[11] In Thurston, an anthropological impulse does not overwhelm his faith but instead supplements and enriches it—he is interested not simply in advocating or debunking miraculous wonders, but rather placing them within a context in which belief in certain hard-to-believe things is its own kind of mystical phenomenon.

• • •

Cardinal Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini—later elected Pope Benedict XIV, he is often called “the Enlightenment Pope” for his attention to scientific method; he was for two decades prior to his elevation to the papacy the Vatican’s official promotor fidei, or “promoter of the faith,” the so-called devil’s advocate charged with debunking claims made on behalf of candidates for sainthood—considered incorruptibility a sufficiently important indicator of sanctity that in his influential 1730 text “On the Beatification and Canonization of Saints,” he devoted several chapters to the question.[12] Asserting that, in most cases, incorruptibility could be explained in terms of natural causes, Lambertini urged the application of medical science to the question of incorruptibility.

According to the Vatican, the Church’s teachings on beatification and canonization have “remained substantially unchanged” since the time of Lambertini’s writings,[13] though it is only in the last several decades that it has actively turned to scientific technology in its consideration of saintly bodies. As Heather Pringle recounts in her book The Mummy Congress; Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead, the Congregation of Saints began in the mid-1980s to employ “pathologists, chemists, and radiologists” to examine “the bodies of ancient men and women interred in church reliquaries.”[14] These scientists found that in many celebrated cases of supposed incorruptibility, the venerated bodies had in fact been surreptitiously, and often rather ingeniously, embalmed using methods brought to Europe by early Middle Eastern Christians well-versed in traditional Egyptian preservation techniques or interred in locations and ways that worked to promote natural modes of mummification. One suspects such discoveries will do little to alter the conviction of those who see in incorruptibles evidence of the miraculous effects of sanctity and the bodying forth of the principle of everlasting life—faith, after all, is the “substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” And perhaps, too, things seen in a way for which there is little evidence. These bodies may not be corporeally eternal, but the belief that finds in them wonders beyond rational explanation is, it would seem, perpetual.

- See Ludwig Freiherr von Pastor, The History of the Popes from the Close of the Middle Ages, vol. 24, ed. and trans. Ralph Francis Kerr (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd., 1933), pp. 520–527. Available at archive.org/stream. The sixteenth-century discovery, veneration, and reinterment of St. Cecilia’s remains are treated at some length in von Pastor’s history, which remains a standard reference on the papacy. Originally published in German in sixteen volumes beginning in the 1880s, the book’s richly detailed descriptions of historical events were drawn, according to the English-language edition, “from the secret archives of the Vatican and other original sources.”

- According to von Pastor, the distinguished Christian archeologist and Oratorian scholar Antonio Bosio expressed the opinion that Cecilia was indeed found in the same position she was in at the time of her death, with her face turned away, though little else can be found in the contemporary record to confirm this observation. Von Pastor also reports that, according to Cardinal Baronius—who the ailing Pope Clement sent in his stead to make the initial examination of the body—the pontiff refused to allow any further examination of the saint’s remains. See von Pastor, The History of the Popes, pp. 521–522.

- Given the unavailability of the body for investigation, it is perhaps Maderno’s inscription, more than anything else, that supplied “historical” evidence of her incorruption.

- See Eti Bonn-Muller, “China’s Sleeping Beauty,” archive.archaeology.org, and Julie Rauer, “The Last Feast of Lady Dai,” asianart.com/articles/ladydai/index.html.

- Leonard Barkan, Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), p. 56–57. Barkan quotes a contemporary letter written by a cleric who claimed that “although the girl has certainly been dead fifteen hundred years, she appeared to have been laid to rest that very day. The thick masses of hair, collected on the top of the head in the old style, seemed to have been combed then and there. The eyelids could be opened and shut; the ears and the nose were so well preserved that, after being bent to one side or the other, they instantly resumed their original shape. By pressing the flesh of the cheeks the color would disappear as in a living body. The tongue could be seen through the pink lips; the articulations of the hands and feet still retained their elasticity.”

- See vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/csaints/documents. Despite its rather dry bureaucratic language, the document is extraordinary for the way it manages to hold in deadpan tension marvels of faith and the administrative minutiae of modernity—see, for example, Articles 107–113, which enumerate procedures for deposing witnesses regarding instances of miraculous healing, including the proper use of tape recorders and computers in taking such testimony.

- Joan Carroll Cruz, The Incorruptibles (Charlotte, NC: TAN Books & Publishers, 1977).

- Indeed, the serene visage and delicately clasped hands of St. Bernadette Soubirous, who appears on the cover of Cruz’s book, turn out to be wax replicas created by the celebrated Parisian mannequin-maker Pierre Imans in the 1920s. Most images of the saint focus on these persuasive yet obviously artificial augmentations.

- Herbert Thurston, The Physical Phenomena of Mysticism (London: Burns Oates, 1952).

- Ibid., p. 238.

- Ibid., p. 240.

- See Fernando Vidal, “Extraordinary Bodies and the Physicotheological Imagination,” p. 17, note 53. Available at mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/Preprints/P188.PDF.

- See “New Procedures in the Rite of Beatification,” sec. I, part 2 (2005). Available at vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/csaints/documents.

- See Heather Pringle, “The Incorruptibles,” Discover, vol. 22, no. 6 (1 June 2001). Available at www.web.archive.org.

Jeffrey Kastner is senior editor of Cabinet.