Old Growth

The lost landscape of James Pierce’s Pratt Farm

James Trainor

Meanwhile the mind, from pleasure less,

Withdraws into its happiness;

The mind, that ocean where each kind

Does straight its own resemblance find,

Yet it creates, transcending these,

Far other worlds, and other seas;

Annihilating all that’s made

To a green thought in a green shade.

—Andrew Marvell, “The Garden,” ca. 1668[1]

Retracing my steps, I drove back down another road named French Settlement which dead-ended in nothing more settled than a bog while checking with OCD regularity the simple directions I had found online (back in the city they had seemed almost annoyingly exact, allowing little room for adventure or mystery or the thrill of discovery, but now they revealed themselves as blithely notional and almost glib, written by someone who’d clearly never been there and never would be). This was beginning to have all the trappings of creeping failure. It had already been a trip of near-misses—a narrowly averted moose collision on a dusky highway, a tire blowout at the crest of a remote mountain pass—and now, after a significant detour, my search for a long-lost Land Art site was threatening to become a pilgrimage to absolutely nowhere. Earlier in the day, at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture twenty miles away, I had mentioned my quest to find the legendary site, anticipating amusing field trip anecdotes and critical opinionating from the artists-in-residence for whom Pratt Farm must surely have been an obligatory stop on any grand tour of local art offerings. After some polite, quizzical nodding of heads, it became clear that no one, not even the school’s director, had ever heard of the place, or its creator, artist James Pierce. That should have been a warning sign that something had gone awry, that Pierce and Pratt Farm had failed to garner a place on the canonical list of Land Art destinations.

Even without the looming threat of violent death, life never got much easier in the area. Around the turn of the century, Pratt Farm was sold along with many surrounding farmsteads to a charismatic proselytizing reformer named G. W. Hinckley. Possessed of copious reserves of missionary zeal, Hinckley set about applying his singular vision of saving the lost children of the Kennebec—the abandoned, orphaned, abused, or neglected sons of destitute farmers, timber men, and wrung-out paper mill workers. Hinckley envisioned a network of linked farms up and down the river, where the young sons of Maine would be given their first and maybe last shot at mastering an agrarian trade from which they could make a dignified living. For several years the project advanced and grew, and Hinckley launched into constructing brick school buildings and sturdy churches and retrofitting existing farms with a sort of Boy Scout ethos and quasi-military organizational discipline. From the 1900s through the 1920s, Hinckley fervently wrote popular tracts and books in which notions of cooperative labor, home, and fraternal belonging and purpose were lauded. He rattled off books with titles like Some Boys I Know, A Long Trip at Home, Some Homes, and Chore Doing, which all celebrated with religious vigor the laborious dignity of sweeping, hauling, chopping, milking, and scrubbing. His lectures promoting this model for other troubled American communities seemed to describe an impossibly beneficent communitarian mini-empire of children situated at the heart of an unloved, overlooked land. (This vast invisible inland never had its painters or poets, never had a Marsden Hartley or Winslow Homer or E. B. White to elegize its atmosphere of loss).

Hinckley’s wholesome utopian project, or Progressive Era delusion, was soon scuttled by the Great Depression, which hit the enterprise hard, prompting the divestiture of land and farmsteads and an implosion of the mission. Many of the children went back into orphanages, state institutions, or foster homes across the country. Pratt Farm, like most of the other land on the east bank of the Kennebec, was sold off—in this case to a Brooklyn banker and his family for a summer home: The Pierces.

Only near the end of his essay does Pierce allow himself to get fleetingly poetic, writing that the maze is “a womb, but it is also a Hell-mouth” and imagining that “those who follow the meanders of the Pratt Farm maze are performing, in essence, a 17th-century dance. They are the incarnation of a Baroque idea, retracing ‘a green thought in a green shade.’”[3] And only as if in passing does Pierce allow himself to divulge the fact that the maze was not the only thing that had cropped up in the meadows at Pratt Farm. Without much fanfare or need for explanation, he describes the maze as the latest “folly” in a “group of earthworks” that, at the time of writing, included what he called a Triangular Redoubt (1971) and a Circular Redoubt (1972)—two berm-like fortification structures, with surrounding trenches bristling with dozens of sharp wooden stakes—and other unspecified works. Taken together, these works formed what Pierce called a “garden of history,” gesturing toward the eighteenth-century emblematic or allegorical gardens that inspired him.

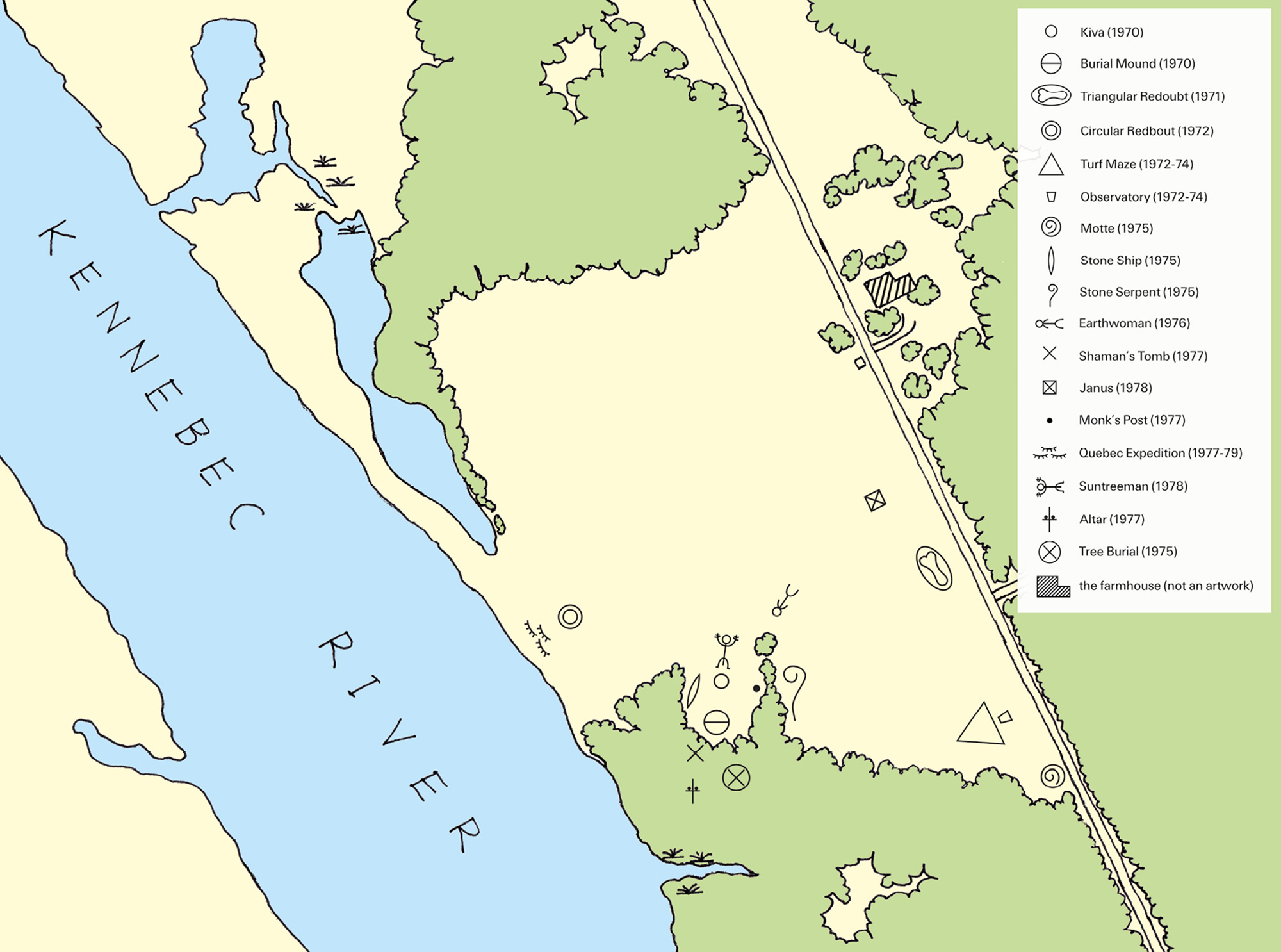

And that was that: his first and last public statement on the subject, even though Pierce had in fact been busy—very busy. He worked the land at Pratt Farm like no one else ever had. Starting in 1970, Pierce began moving the earth around on the seventeen acres of his family’s fallow farmland, meadows, and peripheral woodlands. Unlike Robert Smithson, who that same year began hiring local Mormon contractors to use bulldozers, backhoes, and other heavy equipment to start plowing basalt and gravel out into the shallow Great Salt Lake, Pierce worked alone. Traversing the uneven terrain with the aid of an old Volkswagen minibus that he loaded with earth, stone, logs, and other raw materials, he labored every day from dawn to dusk, according to the neighboring farmer who watched him work. He did this each summer for a dozen years; during the cold months he taught art history at the University of Kentucky in Lexington. Surveying the breadth and scope of his collection of “follies”—there would be twenty in all by the time he was done—his art practice was sweatier, messier, and more maniacally focused on a rustic reformulation of the landscape than his curt cerebral statement about allegorical gardens in the three-page spread of Art International would suggest. He began by excavating a minimalist “kiva” structure near the center of the property in July of 1970—a subterranean pit nine feet across and roughly fifteen feet deep formed in poured concrete with two curving ramps descending to a sunken floor. The next summer, just south of the Kiva, he built a large Burial Mound (based on the ancient funereal hills of the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys, it would be, Pierce asserted, his future earthen tomb), and at the same time began work on his two massive redoubts, the Turf Maze, and a wedge-shaped Observatory of rammed earth for viewing the labyrinth. Forms, structures, and objects quickly proliferated, springing up as Pierce worked his way single-handedly across the farm with Johnny Appleseed élan, scattering historical associations and pan-cultural archetypal allusions everywhere he went.

In 1975, Pierce constructed Motte, a Tower of Babel-like spiral hill eight feet high and twenty in diameter on a low ridge, as well as an arrangement of standing stones outlining the form of a Norse longboat aligned toward the North Star, and another describing a coiled serpent. The same summer, he balanced a massive hollowed-out tree trunk on a pile of boulders in reference to one Bronze Age tradition of open-air burial practices and later evoked another by hoisting a sarcophagus onto rough-hewn posts nestled between pine and birch trees near the edge of a clearing (Shaman’s Tomb, 1977). The latter shared sacral space with a stone-and-wood Altar (1977), which resembled a votive cruciform Neolithic phallus, and the equally priapic Monk’s Post (1977), an obscure nod to a Mongolian wayside marker that acted as both a male fertility symbol and a talismanic object warding off demons.

Evoking darker histories much closer to home, down by the sloping banks of the river and overlooked by the bundt-shaped Circular Redoubt, was Quebec Expedition (1977–1979), the abstracted outlines of three bateaux incised into the hillside and visible from the water. The work elegized another quixotic enterprise that played itself out along this same stretch of river: the ill-fated 1775 covert expedition by revolutionary American forces to invade Canada via a wilderness route up the Kennebec and seize Quebec City from the British. In what reads in contemporary officers’ journals like a jaunty camping adventure devolving into an eighteenth-century version of Apocalypse Now, the journey ended in backcountry misery, misadventure, and death, with hundreds of lost troops dragging themselves over mountains and river rapids that weren’t supposed to be there, succumbing not to bullets (no one ever got to see combat) but instead to drowning, exposure, labyrinthine bogs, disease, starvation, and even a few woefully unlucky deaths from falling trees.

Back out in the central expanse of rolling meadow was Suntreeman (1978), a splayed pictographic sod relief figure with branching limbs, head, and torso doing double-duty as fire pits and Neolithic altars. Upstaging Suntreeman just to the northeast was his Edenic counterpart, the focal point of the farm: Earthwoman (1976). A mammoth fertility goddess if ever there was one—prone, wide-hipped, with generously mounded buttocks, fecund in every sense—in winter she would lie fallow, close-cropped in her tawny turf hide, but she was oriented such that, on the morning of the summer solstice, the sun would rise precisely between her legs and symbolically ensure not only her own fertility (she would soon be covered with spring wildflowers and grow a shaggy mane of wild grass) but also that of the surrounding landscape of which she was a part. Pierce later constructed an earthen pyramidal form several yards to the east of her, Janus (1978), the tip of which contained a ceramic aperture intended to better focus the rays of the sun and strike the cleft between her buttocks every midsummer morning (although whether this homespun light-beam device actually performed as intended remains somewhat dubious).

Overlooking this beehive of procreative energy was a towering, broad-limbed white pine Pierce called the Tree of Life, a lone survivor of an earlier forest spared in the sheep-farming days, which became the axial mooring around which the garden’s menagerie swirled. The ribaldry of Pierce’s raunchy landscape design recalls the lewd emblematic gardens at West Wycombe, England, designed by the late-eighteenth-century nobleman, politician, and libertine, Sir Francis Dashwood. His expansive estate became the scandalous pleasure grounds of the notorious confraternity of ruling class rakes known as the Hell-Fire Club, where Dashwood would stage ever more elaborate forms of hyper-sexualized hijinks, erotic parodies of liturgical rites, and fancy-dress deflowerings. The gardens included a Temple to Venus with a suggestively labial portal, an artificial hill crammed with dozens of erotic classical statues, and imaginative arrangements of shrubbery, flower beds, mounds, and scatological water features designed to suggest various aspects of female anatomy.[4] Pierce’s bawdy forms appear almost tame and encyclopedically ethnographic in contrast, but the intermingled undercurrent of tumescent ripeness—of earthiness, fertility, and death embedded in cycles of agrarian growth and decay—speaks to the same power of symbolic place-making characteristic of Romantic garden design. In this, he had more in common with his English contemporary Ian Hamilton Finlay, an equally outsider intellect working at the unfashionable fringes of Land Art more preoccupied with landscape as a punctuated conversation with the past than as a substance to be ruptured, as artists like Michael Heizer were busy doing.

By the same token, Earthwoman—with its echoes of Ana Mendieta’s earth goddesses, the feminist cosmological alignments and sightlines of Nancy Holt and Mary Miss, and more than a dollop of Jungian symbology, New Age pagan ritualism, and Lucy Lippard’s contemporary pre-history thrown in—couldn’t have been an artwork more in tune with the sensibility of its particular post-1960s moment. Throughout his sprawling yard-sale of a history garden, there were plenty of correlations with what other artists were doing elsewhere—if anyone had chosen to puzzle them out, or if Pierce had cared more for the attentions of the art world. But no one did, and Pierce kept his own company.

And it pretty much stopped there. As Beardsley, who began his 1979 article by describing Pierce as something of “an anomaly”[6] now admits, “Pierce was a historicist, in that he believed that history has continuities into the conditions of the present. He saw himself as part of the narrative or emblematic garden tradition. Historicizing of the sort that Pierce did was out of intellectual fashion in the 1960s and 1970s. He was certainly aware of what was going on around him, but I don’t think he felt any particular affinities with other Land Artists and never cultivated any contact with them. … Nobody knew what to make of him, so they just didn’t react. In the art world there was no interest in him. There was a deep well of indifference that this ever existed.”[7] Despite Beardsley’s repeated attempts to embed it in the flow of art history, Pratt Farm remained a blank spot on the map. For everyone except those who lived near it.

Larry Sexton came to Maine with his family in 1979 to work for the Maine Bureau of Children’s Special Needs and practice family crisis counseling and suicide prevention. After living in a scattered archipelago of lost little towns like East Corinth and Solon, Sexton came across the Pratt farmhouse, dilapidated and vandalized after sitting vacant for nearly a decade, bought it, fixed it up, and moved in with his family in 1990. It was then that he became aware of the warren of earthworks hidden on the Pratt farmland across the road, which was still owned by Pierce.[8] By the late 1980s, it was already covered with high thickets of bramble and fast-growing pine and poplar saplings. Sexton began clearing brush, removing new trees and cutting back stubborn weeds in his spare time. Over time, making his way through the undergrowth with the aid of an antique tractor and hand tools, he restored the land to a semblance of its former state, keeping some sections more cleared than others. In the process, he became the permanent interim caretaker and default curator of the garden of history. He came to be deeply fond of the earthworks and the man who made them. This act of voluntary reclamation did not make him popular. In fact, Sexton soon discovered that many locals had been quite happy to see the last of Pierce when he moved away in 1982 and to watch his earthworks seemingly disappear.

During the dozen or so years Pierce spent creating and tending Pratt Farm, an undercurrent of whispered rumors, a sense of “fear and consternation” as Sexton diplomatically put it, had circulated concerning what was really happening out there on the farm, what odd sacraments those suspicious monuments and forms were actually being used for, what it all meant.[9] Mistrust and superstitious lore—always lurking beneath the surface in this land which still felt the tug of a frontier terror of “savages,” as well as a primeval fear of the mysteries of the forests—was compounded by the clearly sexual and thanatological landmarks beckoning from Pierce’s landscape. It was pagan; it was anti-Christian; it was corrupting the local youth; it was pornographic; it was satanic; it was committing the unpardonable sin of letting good farmland lie undeveloped; it was a place of secret nocturnal rituals and rites, the scene of black-robed Druidical human sacrifice (usually babies); it was the remnants of an ancient meeting place of witches and voodoo practicing slaves, pre-dating (in some variants) Pierce himself, but in which he was somehow implicated as a sort of dark heretical officiate. When a local kid went missing, it was deemed more narratively compelling that she had been sacrificed in “the Pit” (as some locals called the uncovered Kiva) than that she had just stepped onto some Greyhound bus without saying goodbye.

Persons unknown would occasionally deposit such large items of refuse as refrigerators, tires, and oil drums on the property under cover of night, forgoing the expense of municipal dump fees while expressing their disdain for the place. The slow burn of small-town superstition and latent hostility about his motives (at worst), or the stiff indifference and pointed lack of appreciation for what he had made (at best) eventually convinced Pierce that his work at Pratt Farm was done. He moved away and made it clear to those friends he confided in that he wouldn’t mind if it all went to ground. Which it did, quickly.

Years later, Sexton, who never actually met Pierce but developed a periodic long-distance telephone dialogue with the artist, would seek out his curmudgeonly consent to preserve as much of the site as he could. Playing the sedate, mediating therapist to the prickly artist, Sexton understood better than most the deep recesses of trouble marking the lives of the people in the area and tried to mitigate Pierce’s lingering bitterness about their attitudes, making the case that the intensity of antipathy spoke to the plain fact that locals actually believed the earthworks meant something, that they tapped into some profound symbolic aquifer of unease. Rumor was one way of owning their disconcertingly primal power, of making sense of unaccountable things existing in their midst.

Beardsley, now a professor of landscape architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and director of Garden and Landscape Studies at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC, thinks that hostility wasn’t the driving force in halting work at Pratt Farm and drawing Pierce away from the area. Characterizing him as “a pretty cerebral guy,” Beardsley recently recalled that Pierce had told him in the 1970s about the formative influence of Christopher Hussey’s The Picturesque: Studies in a Point of View (1927) on his way of looking at landscape and the evolution of Western cultural perceptions, interpretations, and manipulations of it. According to Beardsley, “doing Pratt Farm, although clearly it was about being in that landscape and it was very spatial and visual, it was also about the circulation of ideas. I was surprised that Pierce didn’t think that the legacy was in the place itself but in its publication as an idea, but it may have been a theoretical and polemical exercise for him. Like writing a book. And at some point you finish the book and walk away.”[10]

One day Sexton’s ancient tractor blew a gasket and couldn’t be fixed. What’s more, his practice took him further and further afield, and maintenance of the landscape stopped. A year elapsed. Nature seized on the hesitation and by next summer, the land was softly covered in undergrowth. After two or three years, the trees had begun to rapidly regenerate and reclaim everything from the farmhouse to the river’s edge. By 2009, a new young forest had reestablished its hold on the land, making it a challenge to visualize anything else having ever been there. But it was. Under the nettles and poison ivy and impassable swales filled with blackberry, behind the thick young birch groves, Suntreeman, Earthwoman, the Janus pyramid, and a host of other follies lay dormant and moldering. Asked if he could help guide a still-hopeful pilgrim into the dense bush and lead him Virgil-like to the major hidden landmarks or even to the gates of Hell, Sexton politely, somewhat melancholically, demurred, admitting to a nagging feeling of personal responsibility for the wildness that had replaced Pierce’s masterwork: “I lost the thread. It slowly slipped away from me, because growth is inevitable and it is constant.”[13] He preferred to stay on his side of the road and tend to his vegetable garden, but gave hints as to where to penetrate the brush and navigate the undifferentiated greenness, warning against Lyme disease and briar patches and the copious ticks and black flies. I did locate the spiral Motte, next to River Road, overtopped with ivy and long wild grasses but still discernably Brueghel-esque in its homespun ziggurat way. Picking my way down through the slopes in the presumed direction of the river, I followed what looked like old forking footpaths that fizzled out into deer tracks or dead-ended in low tangles of thorn bushes. Every now and again, a loamy form or a curiously out-of-place stone would present itself, suggesting a disguised vestige of some human artifice rather than yet another random element of raw nature. But at a certain point the nagging suspicion that everything looks intentional or constructed the harder you look at it began to present itself, even the patterns and arrangements of parts that natural processes throw up in endless combinations with absolute indifference.

Reading the unreadable is tiring. Just as I was about to find the way back to the road, discouraged by deer ticks and stinging nettles, a ragged clearing opened up to the south and there, at the far end, rose the undeniably constructed form of a dome-shaped hill. It was Burial Mound, where Pierce had planned to spend eternity but which would remain unoccupied forever. Retreating to the car, I decided to return the following summer, better equipped to make a thorough forensic survey of the site—to map and document what the death of Land Art looks like when nobody is around to debate the whys and wherefores of decay versus preservation, to chronicle whatever was left before it was all swallowed up.

Pierce had concluded his 1976 essay by musing about the distant future of the garden, imagining that the maze, which served as “a tapis vert, a mandorla, a paradise garden, a wilderness, a sundial, a leaf and snow catcher,” would one day “eventually be covered over and sealed within the earth itself. It may lie there for a very long time.”[14] Entropy he expected. The wilderness, he knew from experience, would lie in wait. But he likely didn’t foresee that the land would be intentionally flayed clean. (If the act of erasure seems callous, consider the fact that most of the ancient Great Circle and Octagon site in Newark, Ohio, was leased by that state to a country club to became convenient landscape features in an eighteen-hole golf course). Today, up on the Kennebec, only Motte still stands, saved by its close proximity to the road and a gradient too sleep to make plowing efficient. On a cool morning in September 2012, in time-honored tradition, two old moldy mattresses lay heaped at the foot of the little hill in offering. Despite the forlorn incongruous sight of a “Posted—No Trespassing” sign staked into the beleaguered monument’s flank by the new owners, someone had seemed compelled to appease whatever remaining gods and demons still resided at Pratt Farm. It appears that “the deep well of indifference” always has room for more trash to be dropped down into it. Meanwhile, the corn, swaying in the late summer breeze, was ripe and high and ready for harvesting.

- The date for the poem is disputed. Some scholars date it to 1651–1652. Thanks to Nigel Smith for his guidance.

- James Pierce, “The Pratt Farm Turf Maze,” Art International, vol. 20, no. 4–5 (April–May 1976), pp. 25–27.

- Ibid.

- Stephanie Ross. What Gardens Mean (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998), pp. 69–70.

- The phrase “garden of the history of gardens of history” is Beardsley’s. John Beardsley, in telephone conversation with the author, 17 September 2012.

- John Beardsley, “James Pierce and the Picturesque Landscape,” Art International vol. 23, no. 8 (November–December 1979), p. 6.

- John Beardsley, in telephone conversation with the author, 17 September 2012.

- According to Sexton, to the best of his knowledge Pierce only visited his land once between 1990 and his death in 2010. The two men missed each other on that occasion.

- Larry Sexton, in conversation with the author at Pratt Farm, 1 September 2012.

- Beardsley, telephone conversation.

- Sexton, conversation.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Pierce, “Pratt Farm Turf Maze,” p. 27.

James Trainor writes about contemporary culture. His work has appeared in Artforum, Frieze, Art in America, Border Crossings, Metropolis, Programma, and other periodicals. He lives in New York City.