Imported Nationalism

The carte-de-visite at the birth of the Mexican nation

Jesse Lerner

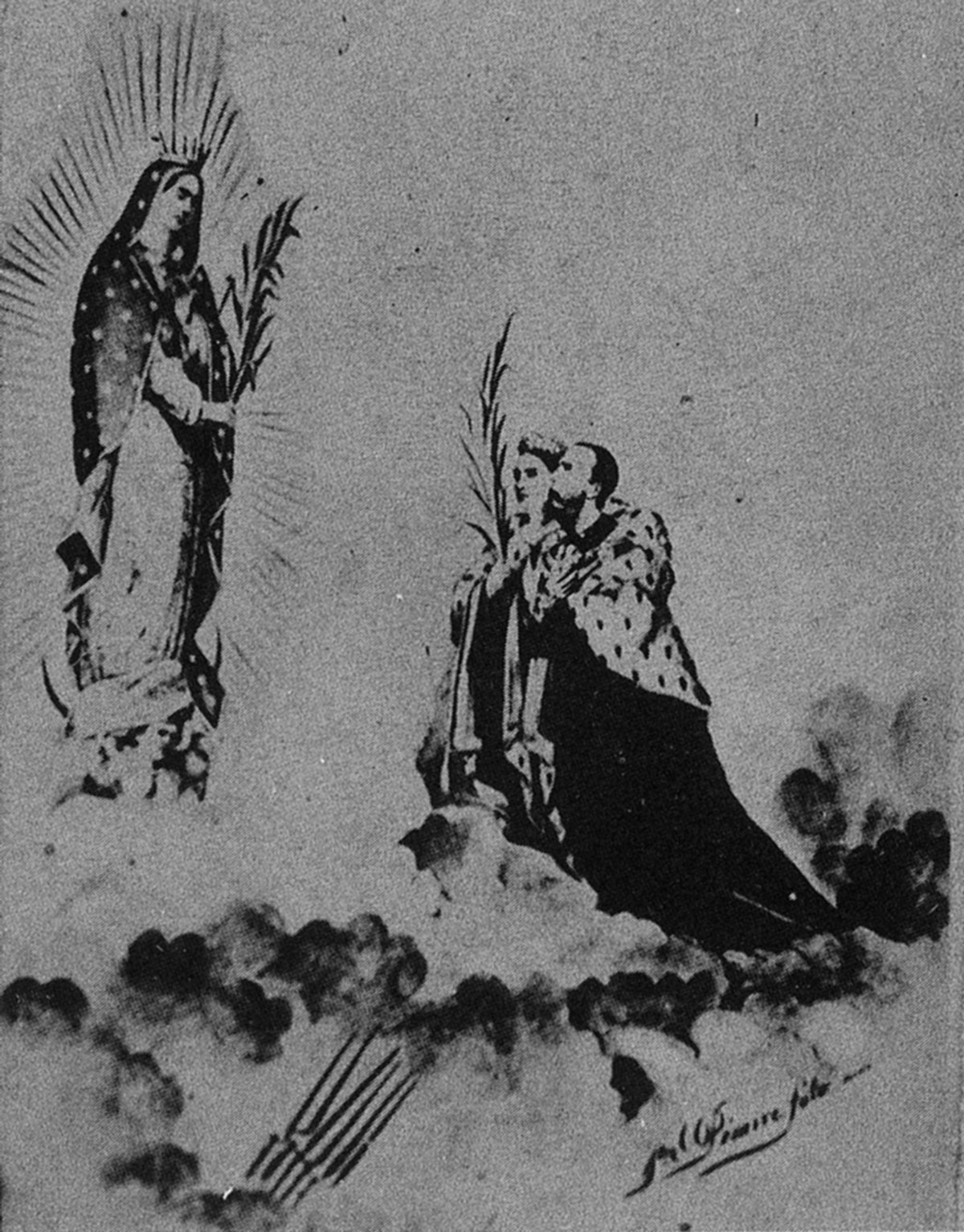

Hovering somewhere between lithography and photography, between nationalism and Europhilia, between supernatural apparition and historical fact, the nineteenth-century carte-de-visite titled Our Lady of Guadalupe appearing to the Emperor and Empress in the Clouds above the Cerro de las Campanas, is a minor curiosity in the history of Mexican photography, a peculiar artifact of the French Intervention (1862–1867). Much acclaim has been showered upon the modernist Mexican photography from the period of the post-Revolution cultural Renaissance—both the work done there by international visitors such as Edward Weston and Paul Strand as well as national artists. Their accomplishments are not at all diminished by the acknowledgement that much of the nationalistic iconography for which these Revolutionary artists are known was firmly in place by the end of the nineteenth century, developed by photographers who have received little praise. The earliest photography in Mexico reveals little that is distinctive. Practiced by and for Europeans, or elites of European descent, it is largely derivative of photography elsewhere, and virtually indistinguishable from the output of studios in Europe or the United States. For this reason, they might be understood not as “Mexican photography” so much as “photography done in Mexico.” The carte-de-visite plays a critical role in the development of a distinctively national photography. Ironically it is the French Intervention, the failed and pathetic dream of reactionaries who imagined imported European royalty was the key to Mexico’s prosperity, which did much to the definition of a uniquely Mexican style.

Though photography had been practiced in Mexico ever since the French made public Daguerre’s invention in 1839,[1] the carte-de-visite was the process that gave Mexican photography its first real mass distribution. The technique was invented by Louis Dodero in 1851, but it was André Adolphe Disdéri who patented the process in Paris in 1854, and went on to become its best-known practitioner. The carte-de-visite utilized a single wet plate negative to produce (typically) eight identical images. The resulting images were printed on light-sensitive paper, separated, and affixed to a slightly larger piece of cardboard. The albumen paper was made from egg whites mixed with salt and applied to the paper, which was then immersed in silver nitrate. The resultant chemical reaction produced light-sensitive silver chloride. The albumen negative, which employed glass plates treated with the identical mixture of egg whites and silver halide, was also used during the early 1850s, but the superior wet collodion process soon superseded this. Prices varied according to dimensions, which ranged from the standard size of about 2 1/2 by 4 inches to the larger “cabinet” (about 4 by 6 1/2 inches), “boudoir” (about 5 by 8 1/2 inches), or “imperial” (about 7 by 9 1/2 inches) sizes. While the earlier daguerreotypes and ambrotypes were accessible to few other than the small Europeanized elite (and foreign invaders, like the North American soldiers of occupation, who posed in front a painted cloth backdrop of the Castillo of Chapultepec in the Mexico City studios of Charles S. Betts and Antonio L. Cosmes de Cosío), the reduced price of the cartes-de-visite made photography accessible to the popular classes.

The uses of this technique were diverse. Portraiture was most important, produced in studios modeled on Matthew Brady’s highly successful New York City gallery. Unlike the one-of-a-kind daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, the inexpensive cards could be distributed among friends and admirers as keepsakes. Francisco Javier Castaño’s biography of the artist Jacobo Gálvez credits the painter with introducing photography to Guadalajara in 1853, when Gálvez returned from his studies in Europe with a “paper daguerreotype” camera. Shortly after this the itinerant photographer Amado Palma announced his presence in Guadalajara with fliers printed with the following text, which gives a good sense of his business:

Amado Palma has the honor of announcing to the respectable public that he has just returned from the United States, and that he has brought with him, for the practice of his profession, German, French and North American mechanisms, all the apparatuses necessary to make portraits or views, with colors or without, and offers—to those gentlemen who would like to try them—portraits which are better than those that they have seen and equal to the most successful ones made recently in Europe, and for the reasonable price of four pesos, with a standard frame.[2]

Later, in the 1860s, the city had permanent photo studios, the shops of Justo Ibarra and Octavio de la Mora. De la Mora, active in Guadalajara from 1865 to 1888, made remarkable wet collodion portraits set in an imaginary world created by painted backdrops and props. Fountains, gardens, waterfalls, and landscapes spotted with castles or temples suggested a simulacrum of distant elegance. Plaster columns and false balustrades supplemented the illusion. De la Mora is credited with introducing to Mexico the use of explosions of magnesium powder for illumination.[3] He later relocated to Mexico City, where he ran a successful portrait studio and worked as a photographer for the National Museum. In addition to taking portraits of their customers, photographers sold to the public the likenesses of well-known individuals. These studio operators did not necessarily have to have access to these celebrities in order to sell their portraits, because cartes-de-visite could also be made by re-photographing an existing image, not necessarily a photograph, and then printing from this copy negative. In Mexico, one of the most popular carte-de-visite images was a portrait by Antioco Cruces and Luis Campa of the liberal president, Benito Juárez, that sold more than twenty thousand copies. His rival Maximilian appeared on similar cards. Collectors often assembled their cartes-de-visite in albums, in which they could place images of themselves, family, and friends alongside portraits of national or world leaders. In addition to individual images, studios offered sets of thematically related series of images. Examples of these include an early sequence of cards representing the already numerous succession of leaders of Mexico since independence. Since there were no photographs of many of these politicians, photographers shot copy negatives of lithographs and printed from these. Another genre produced for mass consumption by entrepreneurial photographers was the series known as tipos mexicanos, or Mexican types. These were representations of a variety of working-class tradesmen and Indian groups, and continued the conventions established by a number of earlier efforts in visual anthropology. In the years 1851–1855, Edouard Pingret, a French illustrator, produced a series of watercolors on the theme of tipos mexicanos. In contrast to portraiture, in these cases the basis for recording a person is not individuality but rather typicality, their representative quality.

The first photographer to market images of tipos mexicanos was probably François Aubert.[4] Aubert was a Frenchman who had come to Mexico in 1854. He learned photography from Jules Amiel in Mexico City and bought Amiel’s studio in 1864. In addition to his series of tipos mexicanos, he made the most complete photographic record of Maximilian’s term in Mexico, as well as numerous studio portraits. He left Mexico shortly after the intervention in 1869. Several other studios offered cartes-de-visite of these folkloric archetypes, but by far the most successful, both artistically and commercially, were those of Antioco Cruces and Luis Campa. They created a series of depicting a variety of Mexican laborers: the water carrier, the baker, the candlestick maker, and so on. As with Pingret’s illustrations, many of the “types” which Cruces and Campa selected (like the tlachiquero or pulque maker, who gathers the sap of the maguey plant to be fermented into a mild alcoholic beverage—later the object of Eisenstein’s primitivist homoerotic gaze in his unedited footage from Hacienda Tetlapayac) emphasize the exotic nature of Mexico for foreign customers. Figures representing different types of peddlers posed with props in front of studio recreations of the settings appropriate to their work. The balance between the artifice of the studio and documentary concerns implicitly yields an elegant tension. Unlike Mexican studio portraits of the era, which typically evoke a world of wealth markers of bourgeois elegance—pilasters draped in cloth, a garden or flowery archway visible in the background—the accoutrements of the studio were used to add ersatz ethnographic authenticity. The images are suggestive of a collaborative process between the model and the photographer. The tipos mexicanos of Cruces and Campa formed part of the nation’s official image of itself, and Mexico displayed these at their pavilion at the 1876 World’s Exposition in Philadelphia.[5] Significantly, they anticipate the folkloric types celebrated by the muralists more than half a century later.

A remarkably rich record of cartes-de-visite images documents the French Intervention in Mexico (1862–1867), the unfortunate brainchild of the emperor Napoleon III. Mexico’s economic hardships had led President Benito Juárez to suspend payments on foreign debts, and the creditor nations—Spain, France and England—moved on Veracruz in an effort to coerce repayment. Although his allies backed down, Napoleon III pushed on, coveting Mexico’s natural wealth and hoping to prevent the United States from gaining sole control of New World resources. Despite a temporary setback in the battle of Cinco de Mayo (1862), the French forces took Puebla after a long siege. Juárez evacuated Mexico City in June of 1863 and General Bazaine took the capital city. With the support of Mexican conservatives, monarchy replaced republican government, and the Franco-Austrian alliance was secured. The Archduke Maximilian of Hapsburg, temporarily stateless after Austria ceded control of Lombardy, accepted the crown, and in May of 1864 arrived in Veracruz with his young wife Carlota. In June they entered Mexico City, and set up residence in Chapultepec Castle. Maximilian’s soldiers managed to chase the Juarista forces far into the north and defeated Porfirio Díaz in Oaxaca, but they never fully controlled the entire country. Completed in March 1867, the withdrawal of the French troops, in deference to the supposed sovereignty of Maximilian’s rule and motivated by events in Europe,[6] marked the beginning of the emperor’s end. The victory of Juárez’s allies, the Union forces in the North American Civil War, threatened to bring a powerful new player onto the scene. Juarista forces drove the emperor out of Mexico City to Querétaro, where he was captured on 15 May 1867. A court martial sentenced him to death, and on 19 June, Maximilian, along with his two loyal generals, Tomás Mejía and Miguel Miramón, were executed on the Cerro de las Campanas overlooking the city.

The French intervention was extensively documented by photographers, both foreign and Mexican. The visiting North American Andrew Burgess created an important record of the war. Burgess had been part of Matthew Brady’s team of photographers, working at the extremely successful New York studio and photographing the Civil War in the United States. Burgess had been in Guadalajara on 4 January 1864, when the French troops took the city from Juárez, and perhaps it was he who took the photograph from gates of the city of Guadalajara of the French troops entering the city. Burgess also took the emperor’s portrait. The photographic studios, like those of Auguste Péraire, Valleto and Company, and Martínez and Co., produced hundreds of copies of a carte-de-visite of the Emperor. Maximilian also had his own court photographer, Julio María y Campo, who was housed in the emperor’s Chapultepec castle. Politically inept, the emperor’s central preoccupation was not waging war with soldiers, but rather with appearances. The carte-de-visite images of this era record a complex, reciprocal process, by which the Emperor and his wife try to become more Mexican, while at least some Mexicans look to the royal couple for cues on how to be more European. On one hand, one sees poses assumed by Carlota in front of the camera studiously replicated in the studio by her privileged female subjects. Conversely, the Imperial court made a conscious effort to surround itself with and to embrace distinctively local elements. Maximilian commissioned portraits of the heroes of Independence from Spain, thus positioning himself as heir to the struggles of 1812. The imperial couple hired Faustino Galicia Chimalpopoca to act as their Náhuatl (Aztec) translator, and Carlota visited the remote Mayan ruins of Uxmal. There are no photographs of Carlota’s visit, but one carte-de-visite shows Francisco Boban, the court archeologist, surrounded by a cabinet of curiosities full of pre-Columbian artifacts, one of the first realizations in Mexico of the political efficacy of this particular invented tradition. The last photograph taken of Maximilian before his execution shows him sporting an oversized, broad brimmed hat like those favored by the Mexican cowboy. Hand-written on a copy of this carte-de-visite at the National History Museum is the caption that makes the symbolism explicit: Maximiliano (charro).[7] It was the European royalty that discovered the nationalist potential later tapped by movie stars like Jorge Negrete and Tito Guízar.

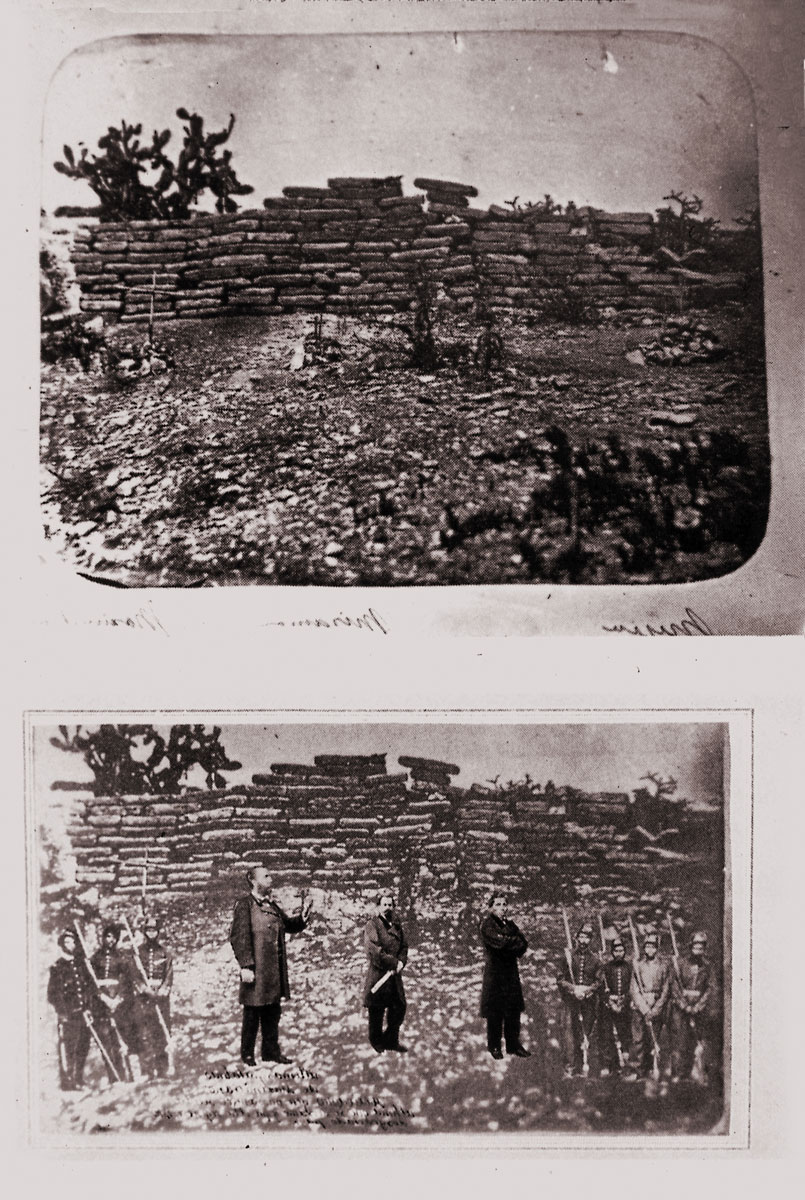

By the 1860s the photographic documentation of world events had become a standard practice, and the tragic appeal of Maximilian and Carlota’s ill-fated Empire made this an ideal subject for market-oriented vendors of cartes-de-visite. An unusually thorough documentation of the execution of Maximilian was photographed by François Aubert, and later widely distributed as cartes-de-visite by Disdéri, Auguste Péraire, the Viennese studios of Auguste Klein and von Jägermayer, Aubert himself, and other photographers. Aubert did not photograph the actual execution, and may not even have been present, but he did record portraits of the three victims, the adobe wall against which the three were shot, the emperor’s clothing after the execution, the embalmed emperor in a glass-covered casket (his eyesockets stuffed with glass eyes borrowed from a statue of the Virgen de los Remedios), and at least two images of the execution squad, one at attention and one at ease.[8]

Aubert’s images were rephotographed, printed and sold by other photographers as cartes-de-visite, but never as deliriously as in a constructed photograph produced from Aubert’s images by Adrien Cordiglia. Using the photograph of the execution site as a background, he superimposed the firing squad, divided into two halves and placed in the lower corners, and the three victims. The images of the victims are themselves constructions, assembled from headshots placed on borrowed bodies. Beneath Maximilian his last words are written in by hand: “Mexicans, may my blood be the last that is shed and may it revive this unhappy country.” The figure of the emperor appears larger than the two generals or the members of the firing squad, as if to emphasize his relative importance. In one sense, this unusual image seeks to construct the decisive photograph that Aubert never took, the actual execution itself, with the executioners and victims placed together at the site of the event. But more than simply attempting to reconstruct the execution scene, Cordiglia’s composite draws on other pictorial traditions and hints at an unexplored potential of the medium. Other artists, especially lithographers, were free to invent their vision of this scene, and later Edouard Manet painted three versions, based on prints and on these photographs.[9] Contemporary prints commemorating the same event combined several scenarios into a single image, such as an anonymous Italian lithograph of the same year that integrates a portrait of the Emperor with scenes of “the departure from Miramare,” “the arrival in the capital city,” and “the betrayal.” Many of these circulated as cartes-de-visite reproductions.

Less than three decades after its introduction, Mexican photography was a surprisingly mature medium with distinctly national characteristics. Long before the modernists of the 1920s, photographers turned their attention to the indigenous faces and traditions, the characteristic landscapes, and the iconic national symbols in ways that sometimes anticipate the Post-Revolutionary Renaissance. Like the image of the apparition of the dark Virgin before the Austrian royalty, Mexican photographic practice in the nineteenth century was a mixture of imported and autochthonous elements. The juxtaposition of the imported archduke and Mexico’s patron saint is not an inappropriate one. Maximilian had commissioned an oil of the Virgen de Guadelupe from Joaquín Ramírez, one of Mexico’s leading academic painters. Though the Royal Guadalupana ascension is perhaps technically awkward, it embodies a series of revealing contradictions, and like many of the images of these early photographers, in all their hybrid complexities, achieves a rare beauty.

- On 3 December 1839, three and a half months after Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, Isidore Niépce, and François Arago gave the first public demonstration of the daguerreotype before the French Academy of Sciences, the printer Louis Prélier landed in Veracruz with two daguerreotype cameras that he had purchased in Paris. News of the daguerreotype had already arrived in Mexico. Prior to revealing the details of the photographic procedure in August 1839, Daguerre made public the news of his discovery, as early as January of the same year, and displayed sample images. A Mexico City newspaper, El Diario del Gobierno de la Republica Mexicana, gave the first account of the daguerreotype in Mexico on 5 June 1839.

- Quoted in El que mueve, no sale! Fotógrafos ambulantes (México D.F.: Museo nacional de culturas populares, 1989), pp. 32-33.

- La Bandera de Jalisco, vol. 1, no. 28 (6 June 1888), p. 4.

- Philippe Roussin, “Photographing the Second Discovery of America,” in Mexico Through Foreign Eyes (New York: W.W. Norton, 1993), p. 97.

- Olivier Debrosie, “Fotografía: verdad y belleza: notas sobre la historia de fotografía en México,” México en el Arte, no. 23 (Fall 1989), p. 7.

- The Prussian defeat of Austria made Napoleon’s alliance considerably less valuable, and the mounting cost of the entire effort made it unpopular in France.

- Mexican cowboy celebrated in the national cinema of the Golden Age.

- Even decades after the execution of Maximilian, the execution site continued to be a point of interest, and in the early 20th century photographers such as François Miret and C. B. Waite documented and sold views of the chapel later erected on the spot.

- Juliet Wilson-Bareau, Manet, the Execution of Maximilian: Painting, Politics and Censorship (London: National Gallery, 1992).

Jesse Lerner is the director of the new experimental documentary film The American Egypt. He teaches media studies at the Claremont Colleges. Lerner is an editor-at-large at Cabinet.