All that Glitters

The martial moment of Israeli New Year’s cards

James Trainor

Allenby Street in Tel Aviv is about as unrepentantly seedy, loud, and ungentrified a major boulevard as you are likely to find in the fabled Bauhausian White City. It has stubbornly sidestepped the upscaling of the city and continues to cloak its former quasi-grandeur behind veils of wafting soot and obstinate rows of diesel-choked ficus and eucalyptus trees. If it is cheap jewelry, polyester wedding garb, questionable electronics, or third-rate Judaica that you need, this is the place to visit. And in the weeks before Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, it is where the many shoebox newsagents and stationers drag their racks of Shana Tova (literally “good year”) greeting cards out onto the street—some new, some less so, the majority belonging to a more distant past, the amount of indeterminate grime and grit on them inviting casual forensic analysis of relative age and undesirability. Taken in sum, they are evidence of overoptimistic wholesale buyers who never imagined that the once-pervasive tradition of exchanging New Year’s cards might wither and all but perish.

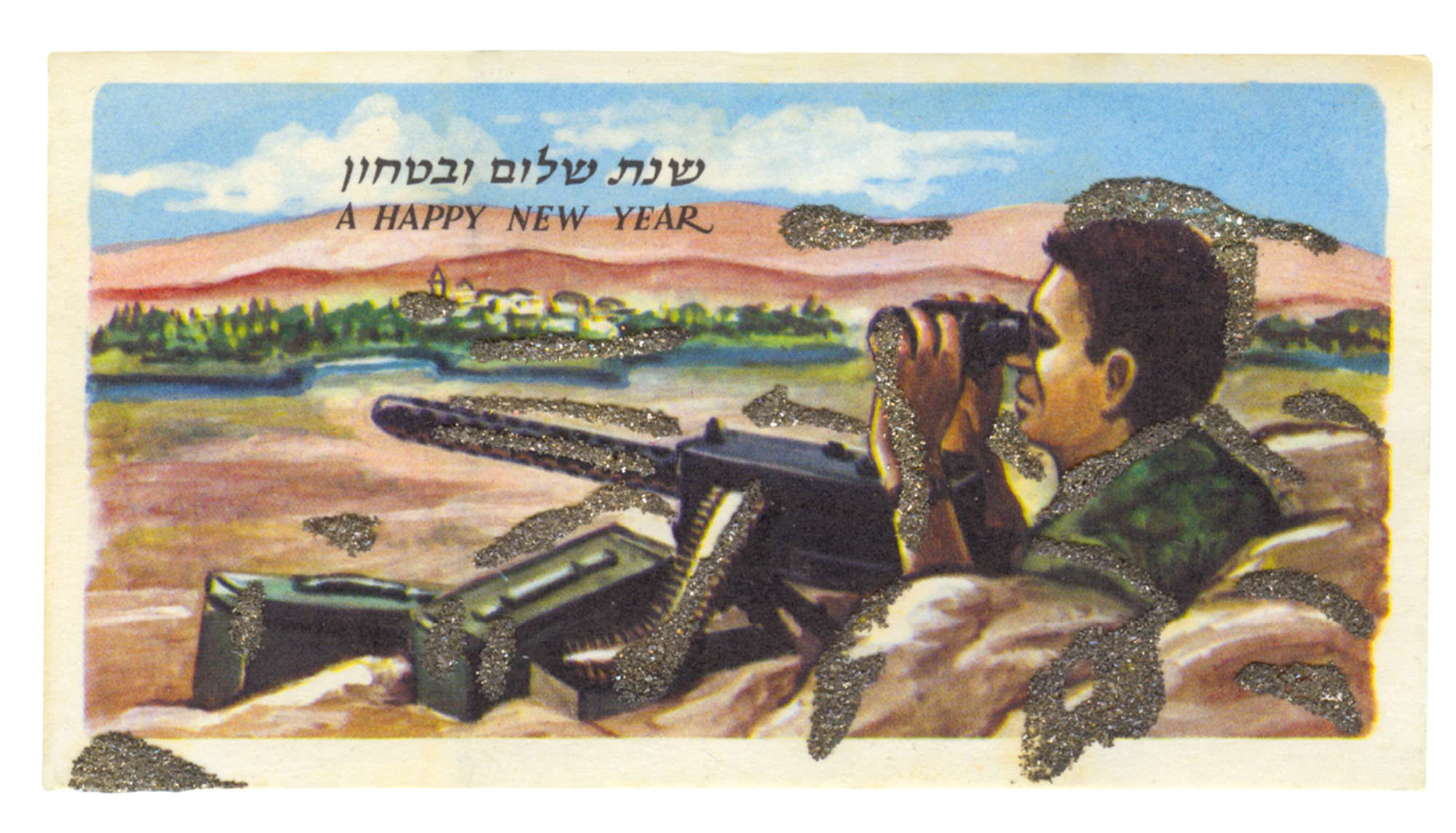

It was here one September, on my first visit to Tel Aviv, that I found myself in a forlorn open-air mix-and-match museum of indecipherable, incompatible iconographies. There was the reassuringly stereotypical visual smorgasbord of shofars, Talmuds, doves, fruit-laden cornucopia, and tanned youths performing folk dances in quasi-biblical garb. There were also the obligatory depictions of Theodor Herzl (the nineteenth-century father of Zionism), always using the same iconic photograph of him gazing out over the Rhine in Basel incongruously transferred into various scenes as needed, such that he could be summoned to greet the arrival of a 1950s ocean liner at Haifa or to oversee a new electricity plant. And everything festooned with gold and silver glitter, hastily applied by hand in order to add festive glamour to each scene.

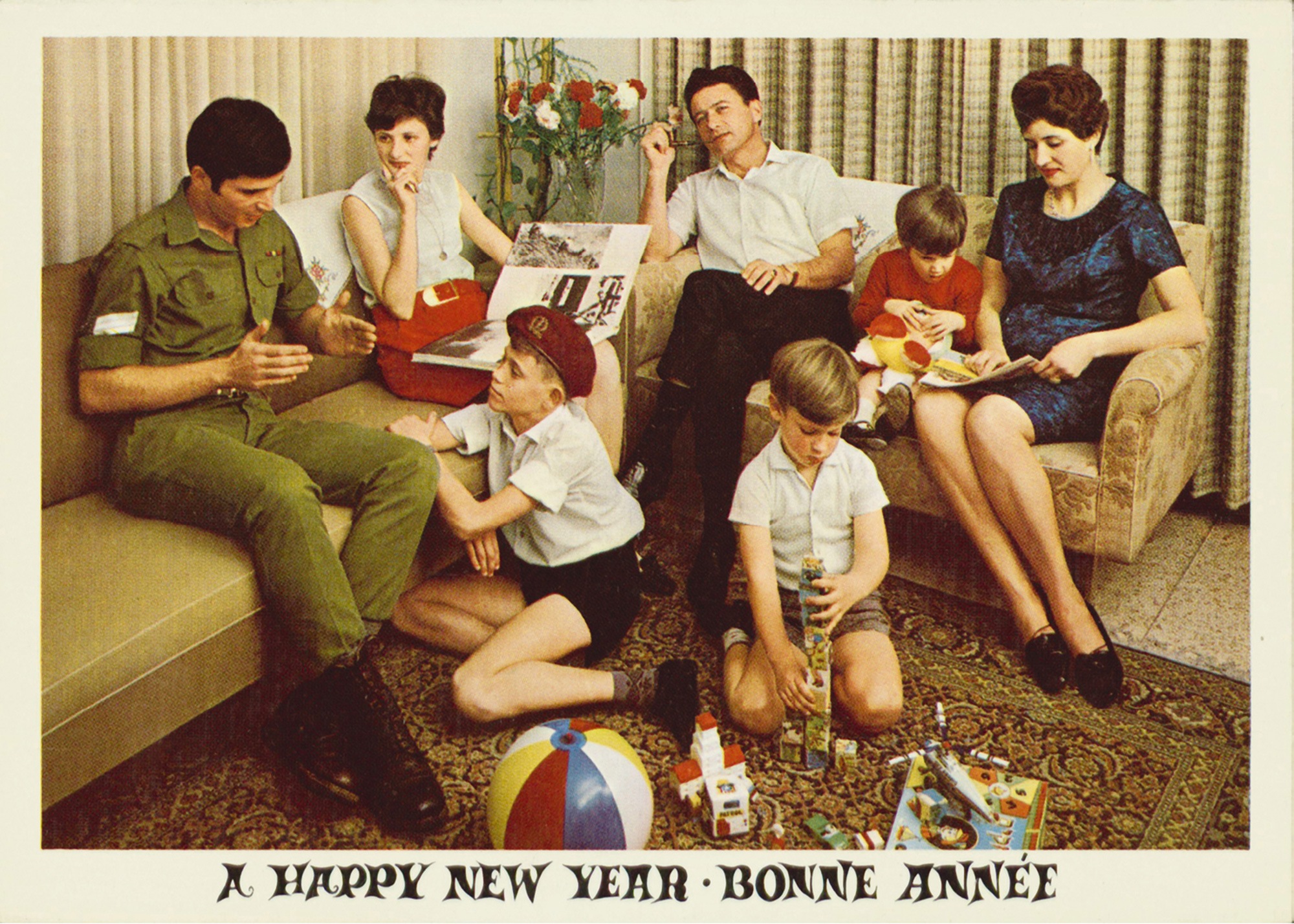

So far, so good. But alongside these more predictable motifs, all captioned in Hebrew with the occasional “Happy New Year” or “Bonne Année” printed beneath, were crudely painted images of burning tanks and dive-bombing planes, helmeted men lobbing hand grenades at invisible foes and smartly uniformed ranks of handsome men and women marching beneath ancient buildings.

More familiar with the pictorial conventions of North American greeting cards, I had never before encountered images of implied carnage, collective aggression, and ebullient military spectacle as a way to convey fond wishes to loved ones. Certain that the Hebrew captions held some answers, I scooped up as many cards as I could and began asking friends for translations.