Colors / Hooker’s Green

Botanical verisimilitude

David Frankel

“Colors” is a column in which a writer responds to a specific color assigned by the editors of Cabinet.

It’s not easy being green and having to spend each day the color of the leaves, William Hooker must have thought—or at least, if his powers of sympathy never led him to imagine being the color of the leaves, he certainly pondered the difficulty of trying to paint it. A London artist of the early nineteenth century, Hooker, like his Belgian counterpart Pierre-Joseph Redouté, was the master of a particular specialty, the minute description of individual specimens of flora. Where Redouté’s reputation rests on flowers, though, and particularly on roses, Hooker painted fruit. That meant showing their leaves, for which he is said to have concocted a sort of base color by mixing Prussian blue and a yellow called gamboge. Though differently arrived at today (apparently phthalo green and isoindolinone yellow are one set of ingredients), the green that resulted—Hooker’s green—is still made and marketed by that name, and is valued by landscape artists as a shade that they can lighten, darken, or otherwise play with as needed to render natural-looking foliage.

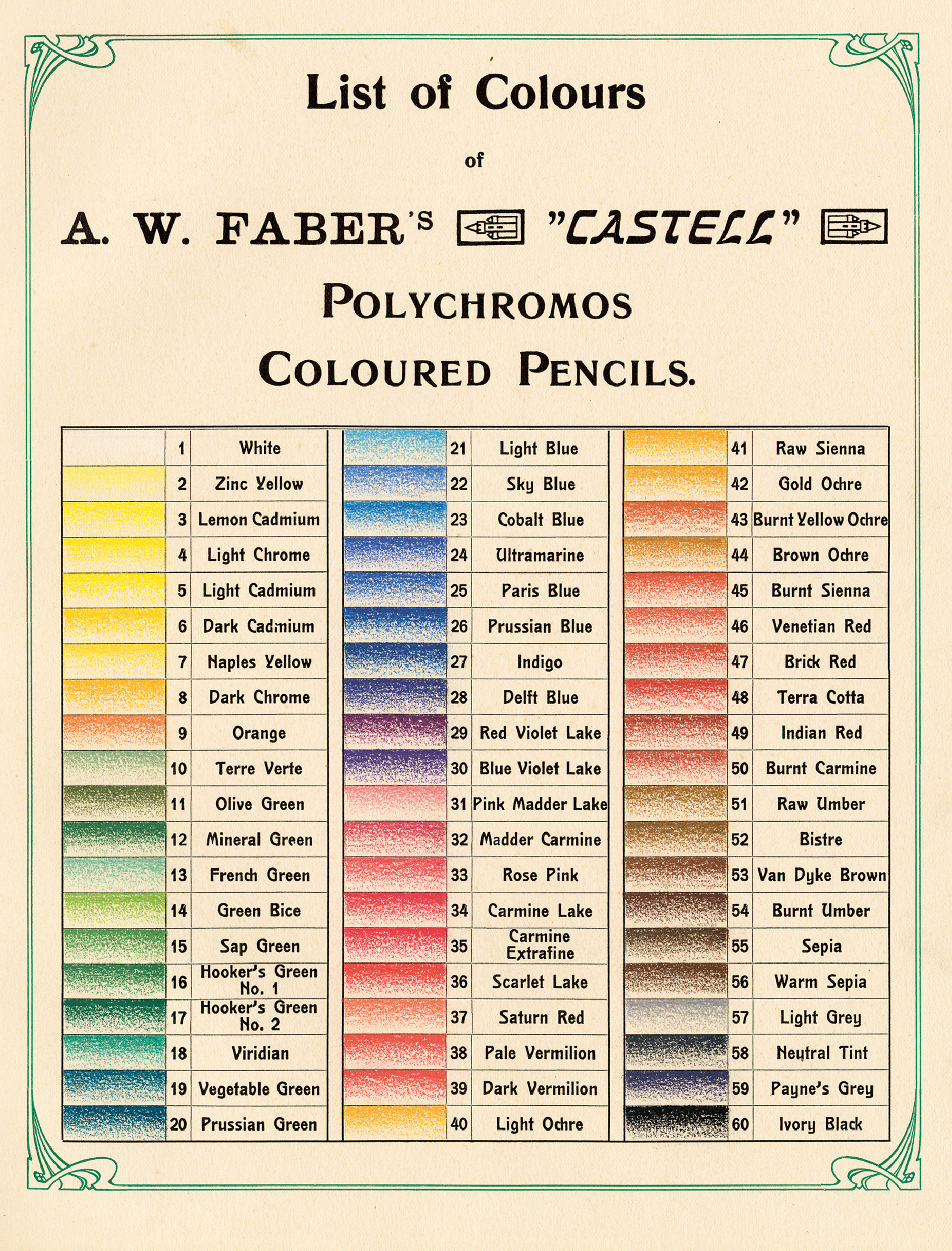

How many shades of green are there? Touring Ireland in 1959, Johnny Cash found forty in that country alone, and wrote a song to that effect, though it was probably some Barry Fitzgerald–type he met in a pub who gave him the number. There are actually far more than forty, of course, enough for Hooker to find mixing them a chore, and his green is an early example of standardization, a formula to be reproduced again and again. There are many such greens, each tied to a particular position on the scale between yellow and blue: forest green, hunter green, kelly green, Lincoln green, and a long list more, not to mention differently named colors like olive and teal.

Painters once proudly ground their own pigments. Indeed, the grinding and mixing of pigments was a kind of art in itself, “endowed with alchemical powers and jealously protected as a secret knowledge,” as Thierry de Duve writes in “The Readymade and the Tube of Paint,” a terrific Artforum essay of 1986. In a discussion of Marcel Duchamp, de Duve describes artists’ passage from arduously acquiring proficiency in grinding their own colors to simply purchasing premixed tubes of paint, commercially manufactured, packaged, and sold. In the late eighteenth century, when Hooker was growing up, new production and packaging technologies for paints began to emerge, first for watercolors, a few decades later for oils. Much of the painting of the later 1800s depended on these packaged paints. In de Duve’s argument, Duchamp acutely saw that this art relied on a ready-made, manufactured commodity, and that it was therefore in some way a readymade itself. “A tube of paint,” Duchamp once said, “ … is not made by the artist; it is made by the manufacturer that makes paints. So the painter really is making a readymade.” Even when the artist mixes colors from different tubes to arrive at a color of his or her own devising, “it’s still a mixing of two readymades.” In this view, the modern painter is not so much creating something as choosing among commodities, just as Duchamp famously chose a bicycle wheel and a snow shovel and in doing so defined them as art.