The Virgin Doesn’t Care Why You Fall

Ex-votos and the imagery of salvation

James Oles

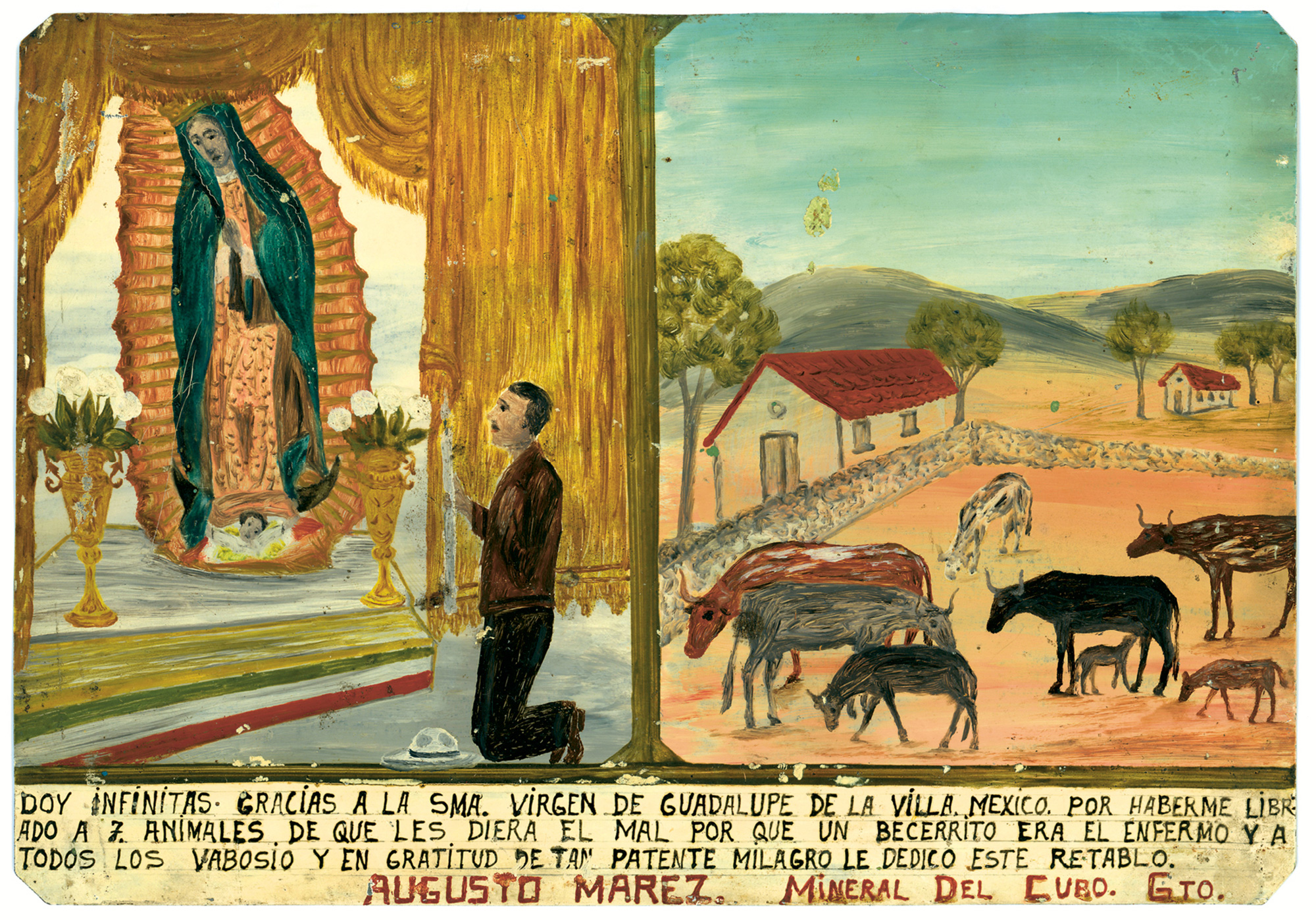

Ever since the first Cro-Magnon hunter carved a hunk of ivory into the shape of a mastodon in thanks for a delicious steak, images have commemorated humans’ gratitude to divine forces. In the modern Catholic world, votive objects fall into two rather distinct categories. Charms and amulets—in the shape of hearts or cows or trucks or even plots of land, and made of metal or wax or wood—record individual prayers, and thus anticipate successful resolution (recovery from illness or getting that horse you dreamed of). Ex-votos, which are more elaborate and historical in that they are not generic offerings but show instead particular events, are explicit demonstrations that your prayers were answered. As their Latin name indicates, they commemorate vows made at a critical moment—from the sickbed, aboard a foundering ship, at the moment of electrocution: get me through this and I will show everyone that I survived thanks to your divine intervention. The dead don’t commission ex-votos.

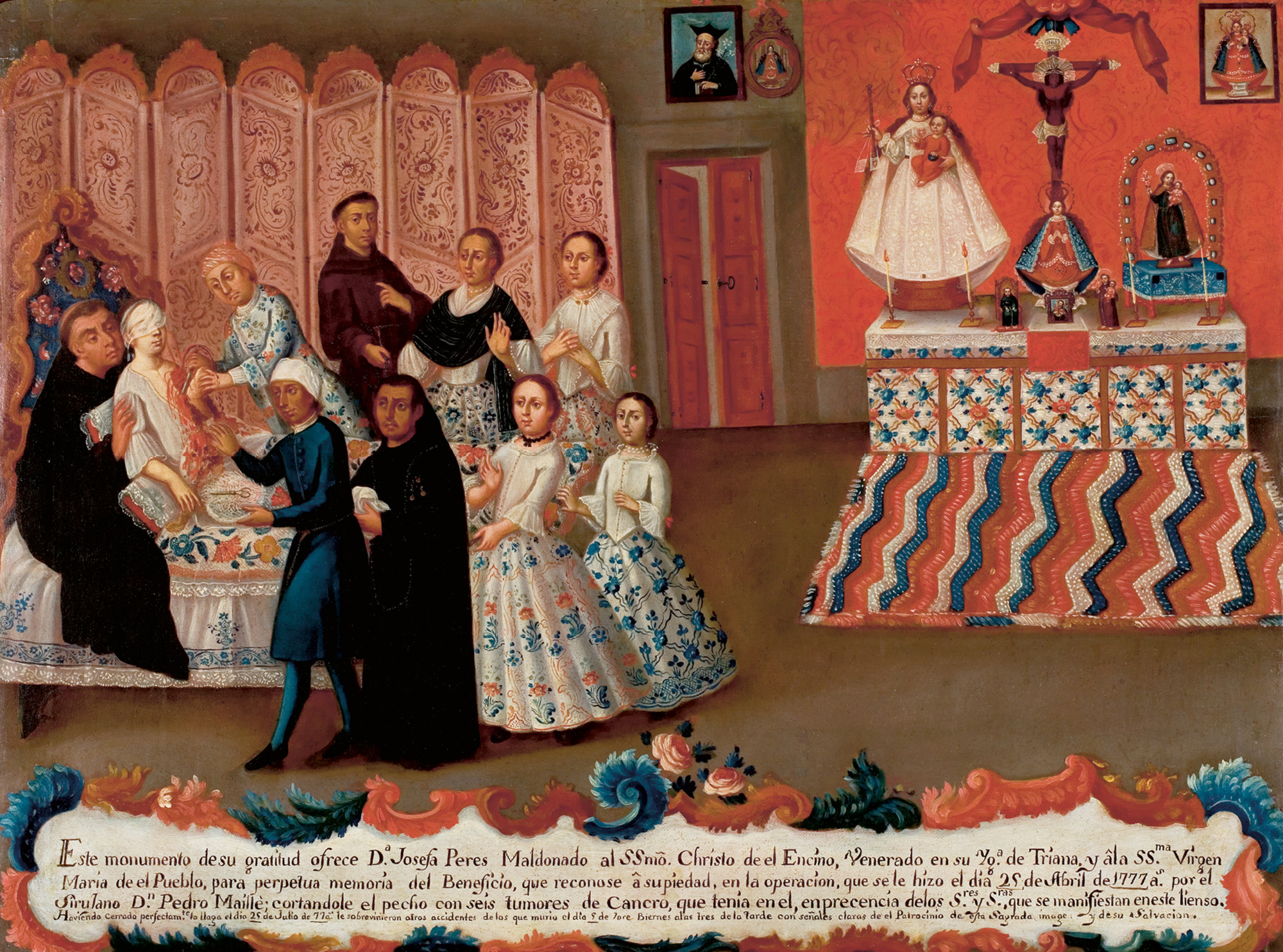

Although often depicting scenes of the greatest intimacy (the embarrassment of falling off your steed; having your left breast surgically removed), and today decontextualized in books or collectors’ homes, ex-votos were originally intended for display in the church, as public proof of the miraculous powers of a specific image, of a specific representation of Jesus, the Virgin Mary, or a saint understood to be an effective intercessor with God himself. Collaged together, they repeated the same story: this icon works. Although their historical roots are numerous (the Victory of Samothrace was an ex-voto of sorts), visual testimonials of salvation from death flourished during the Counter-Reformation. As public offerings, they contradicted the private devotion of Protestantism; as demonstrations of the power of prayer to change the course of human events, they denied the trap of predestination. And they played an instructive and pedagogical role: like later melodramas and reality shows, they moved audiences to tears with stories anyone could relate to. They also encouraged dropping more coins into the adjacent collection box: this icon pays.

With some exceptions, as the pictorial genre solidified across Catholic Europe and the Americas in the seventeenth century, artists followed a standard compositional format. A narrative scene, with or without architectural or landscape elements, is sandwiched between a cartouche below and the divine image above, which is usually floating in the clouds, but is sometimes—perhaps in an attempt to rationalize mystery—shown as a devotional object placed on an altar or wall. Some ex-votos are rather austere: in an early example now in the Louvre, French painter Philippe de Champaigne depicts two praying nuns to commemorate his daughter’s recovery from paralysis in 1662; in others, kneeling figures pray to the image in a nondescript space, and the text says only that some “favor was received.” But those that touch us most show the illnesses and accidents, fears and tragedies, of the time: they depict events from daily life that were not daily occurrences but were nevertheless rarely recorded in histories or journals, that wouldn’t have even been worth mentioning in newspapers until they began catering to the morbid obsessions of readers.