For the Simple Reason Is

Vigilance as a fugue state

Brian Dillon

It is getting on toward autumn, and this is what she must do with her day. Up early, switch off the alarm, unbolt the doors, and out into the garden in slippers, dressing gown, overcoat. Low sun on her flat dusty curls as she passes along the back of the house, and against the windows, which are shuttered still inside, behind the net curtains. The birds mad at this hour. Starlings. The young ones from the spring, reared and grown, little hooligans now. She has got a bag of seed out of the shed. From here the feeder looks like a small, startled red man, hung from that second stretch of clothesline she had one of the boys put up this time last year. It’s empty now, the feeder, light and swinging in the breeze.

Is that why she stops? Because it oughtn’t to be empty already? No, that’s why she’s up and in the garden. Is it then some detail of the surrounding scene—a pair of breeze-blocks tucked into shadow, some irregularity of the fence beyond, the almost leafless tree above—that sends her bustling back inside for her camera? Those roses, perhaps, over on the right there: oddly headless, not a single withered bloom. What has she seen? She has the camera in both hands, but she’s stiff as always on her left-hand side and it’s still askew when she takes the shot.

What exactly am I supposed to be looking at?

For at least forty years and very likely more, my father’s sister maintained a feud with her next-door neighbors (both sides) that slowly came to dominate her life, a quarrel from which it seemed to us—the rest of her family—she drew a malign sort of energy and out of which, despite the best efforts of all, she could not finally be extricated.

She had inherited the problem—I almost wrote project—from her parents, who moved into the redbrick suburban Dublin house with their three children (then in teens and twenties) in the late 1940s. Who knows how it all began. My grandfather was a bully and a snob, a former soldier and police sergeant with a greatly inflated sense of his moral and social standing. Some measure of his character may be gleaned from the fact that when he retired early from the police in the 1950s, he got a job as a debt collector—but a debt collector for a chain of toy stores. Imagine the old bastard cycling up your street one fine spring morning, his saddlebag full of confiscated gifts: the spirit of Christmas repossessed. My guess is a man of his sort easily took offense at some small infringement of a boundary: a hedge trimmed too far in his direction, a woodpile carelessly edging into his garden, something of that sort. Maybe his children rolled their eyes at the sight of Daddy in the garden at dusk, his Hitchcock silhouette tapering to a pair of bicycle clips, pointing and shouting at the hedge.

Things must have escalated when he gave up work completely, and his natural officiousness was circumscribed by illness and immobility. By the late 1970s, when I was old enough to notice, he spoke of little else on our Sunday afternoon visits. They—here he would jerk a thumb in either direction—had invariably committed some fresh misdeed, frequently involving their moving by a few inches a section of the rusting cordon of corrugated iron with which he was gradually surrounding his property. He could hear them on the other side, he said, cursing at him all day long. My father and another sister had escaped, hopped the fence, married and emigrated respectively. But this aunt, then single and middle-aged, was trapped inside the precincts of her now widowed father’s monomaniac rage. As his health failed, she seemed to elect herself heir to all his spite and fear, and even went to work on her own distinct campaign against life in the south Dublin suburbs, detailing in countless letters of complaint to businesses and institutions the almost daily slights and derelictions she suffered at the hands of bus drivers, shop assistants, priests, and policemen who failed to help in the matter of the neighbors.

Of course I should like to know what she and her father were really afraid of. To the neighbors and obnoxious local functionaries was added a list of wild youth: teddy boys, corner boys, cider boys, gurriers. Kids from the local housing scheme. Whether any of them posed a threat is moot. The source of all this anxiety and animus was rather, I think, their mere proximity: a sense that having installed himself in what looked in the 1940s like lower-middle-class security, my grandfather had not come far enough. Fenced away and pensioned off, he still could not stop the down-at-heel city—that is, the recent past—from leaning drunkenly on his privet hedge, or scattering sweet wrappers on his lawn.

My aunt’s case was different, and worse. Her name was Vera—quite a name for a lifelong fantasist. In my first memories of her, she is fat, loud, vulgar, not always unhappy. She still had a job then, having worked it seems all the sweets counters at all the cinemas in town. She liked to say that as a girl she’d been beautiful, and might have become a model. Packed off in her teens to the care of an uncle in Birmingham, she gorged on clothes and makeup and a temporary freedom. It might have been this unruliness that got her sent home again, where tuberculosis stole what remained of her youth. I can’t say how long she spent at the sanatorium but the disease, or rather its violent remedy, took away a lung too (the left) so that for the rest of her life she listed visibly to one side.

With her relatively minor debility, I suppose, came a great and lasting shame, or disgust—she could never grow fat enough to fill that hole in her side or disguise where her body had been breached. Her prospects, in the old-fashioned sense, must have faded. In a matter of months, perhaps a year or two, she had been positioned as the daughter who would not get away, but stay at home to be looked after and in time do the looking after. She became an energetic hypochondriac, ever vigilant for a sign that her body was under attack once more. The battle with the neighbors was merely an extension of the vulnerability she already lived with, lived through—a feeling that all her borders, intimate or domestic, were ruinously porous, subject any moment to undignified invasion.

Her personality slowly curdled; she became an impossible person. By the time I knew Vera, her residual boisterousness was being swamped by simple aggression and what is called, or was then called, self-pity. At home we learned, my two brothers and I, to laugh at her behind her back, treat her as a comic grotesque without a whit of self-awareness. Vera at the front door on Christmas Day: Do you know what it is, I couldn’t look at a turkey. Vera some hours later, stuffed with turkey and belching freely, ruing her destroyed innards. Vera half-cut and flummoxed in front of the TV: Who’s that? He’s got terrible old looking, that fella. But also: phoning night and day to say they were at it again. Who? Head-the-ball next door and his slut. Summoning her brother in the small hours to observe by flashlight her trampled flowerbeds, a hole in the hedge, the newly rakish angle of a corrugated sheet she had straightened in the daytime. Marshaling her evidence. Making scenes, demanding action, growing angry when my father refused to use his contacts in the civil service to ensure that something was done. Years later, we discovered she had written to a relative among the judiciary in London—the late Sir Brian Dillon, as it happens—and received a bemused, polite, and firmly negative reply.

There was a favorite phrase of hers. For the simple reason is. She meant for the simple reason that—or more simply, because. She spoke it hard and slow, as if you were the stubborn, deluded, mistaken one. She could not sit in her garden, she said, for the simple reason is they’re out there all the time. Something must be done, for the simple reason is these nerves will take no more. But she would not move house after her father died, for the simple reason is you don’t know who you’d end up living beside. Sometimes she’d stop before she got to the thing itself, letting this phrase hang in the air, as if to say: can you not see what the simple reason is? To us, the phrase was grammatically redundant, overused, and idiotic. For her, it was the solid, painful expression of self-evidence.

While I was growing up, it seemed increasingly that she mediated a world bristling with insult and disappointment through things, through gadgets. Enough stuff to build a barricade. Vera was the first person I knew to own a cassette recorder, a VCR, a color television. In the mid-1980s, she bought a huge Hitachi ghetto blaster, hardly used it, then passed it on to us. When she upgraded her TV, we got the cast-off, practically new. She never gifted us a camera, so her collection grew, perhaps in hope she’d one day take a pleasing or even competent snapshot. I can see her now with her big white plastic Polaroid OneStep, standing in the sun by an urn full of hydrangeas, growing hot and furious that none of her efforts to frame and fix the world came out looking the way she planned.

After she died, we found she’d kept all her cameras. I cannot swear to the model she used to take these photographs in the last decade of her life—it was perhaps a little Canon point-and-shoot she bought in the 1980s. I have in my possession sixty-one of these pictures, plus a few negatives, but I left handfuls more behind when I helped clear out her home. She has photographed the house and environs from numerous angles, paying close attention to all the borders of her property, all points of possible exit and entry, the places where she might be overlooked. Here are the fat hedges that flank the back garden, held up in places by long wooden props where, like her, they have leaned heavily to one side. Views from inside the back door at night, where the camera’s flash has hit the jade-green frame but not the scene outside. Blurred or otherwise botched images of door handles, window sills, opaque expanses of curtain. An almost abstract arrangement of shadows and edges in concrete, metal, and soft wood: somebody, she thinks, has been inside her new garden shed. Snapshots where the flash has bounced off the sitting-room window and swallowed whatever, or whoever, she was trying to catch outside—erased her own reflection too.

She married in her fifties, but her husband died a decade later. (Her brother gone in the meantime, his wife also.) Still, she was not alone—though the boys, her nephews, did not seem to understand what she put up with, day upon day. She needed proof, something to show them when they came round—the younger two anyway—to trim her hedges and mow the lawn. She was, after all, the daughter of a policeman, the granddaughter too; it was not beyond her to amass the evidence. It was simply a question of vigilance and speed, recording it all before it was washed away or overgrown. That was the problem: always later, when she pointed in the garden, people saw nothing. And so with her camera she surveyed the frontiers of the place where to her surprise she still found herself. Those borders seemed lately to have moved inside the house, in among her pictures and ornaments and the patterns of her carpets, closer than ever before.

I last saw her about five years before she died. Ten years before that, she’d dramatically disowned me. From now on I’ve only the two nephews, do you hear me? On visits home to Ireland, I resisted getting drawn into seeing her again. Her age and frailty did not move me. I had learned certain facts about her, about her dealings with my mother while she was sick and even dying, about her attitude to my brothers and me, that convinced me she was not merely troublesome, old, and afraid but actually wicked, a monster of jealousy and self-regard. Others among the family (my brothers, and my mother’s sisters) took pity, found the patience to listen now and then to her tirades, tried to get her to see someone. I thought I was the only one who had seen through her, divined her essential viciousness, which I regarded, I suppose, with the same frustration and certainty with which she regarded her neighbors. Except, of course, that I could turn away.

When at last I relented and went to see her I was quite prepared for the monologue, the blame, the fantasies, the sanctimonious memories of Daddy, whom she must have hated above all. I knew she had lately driven her sister, who’d come back on a visit after thirty years in New Zealand, out of the house for having, so she claimed, gone in search of her will—but also for the crime of treading too heavily on the stair carpet. I knew she was now genuinely ill with diabetes and more, but entirely resistant to the suggestion she might have psychological problems. She was consumed in her late seventies by the idea that somebody—it was not even clear she meant the neighbors anymore—was regularly invading her property and cutting her roses. One day, my younger brother watched her bustle into the garden and snip half a dozen blooms herself, then march back in the house with the evidence. Look, look what the bastards have done.

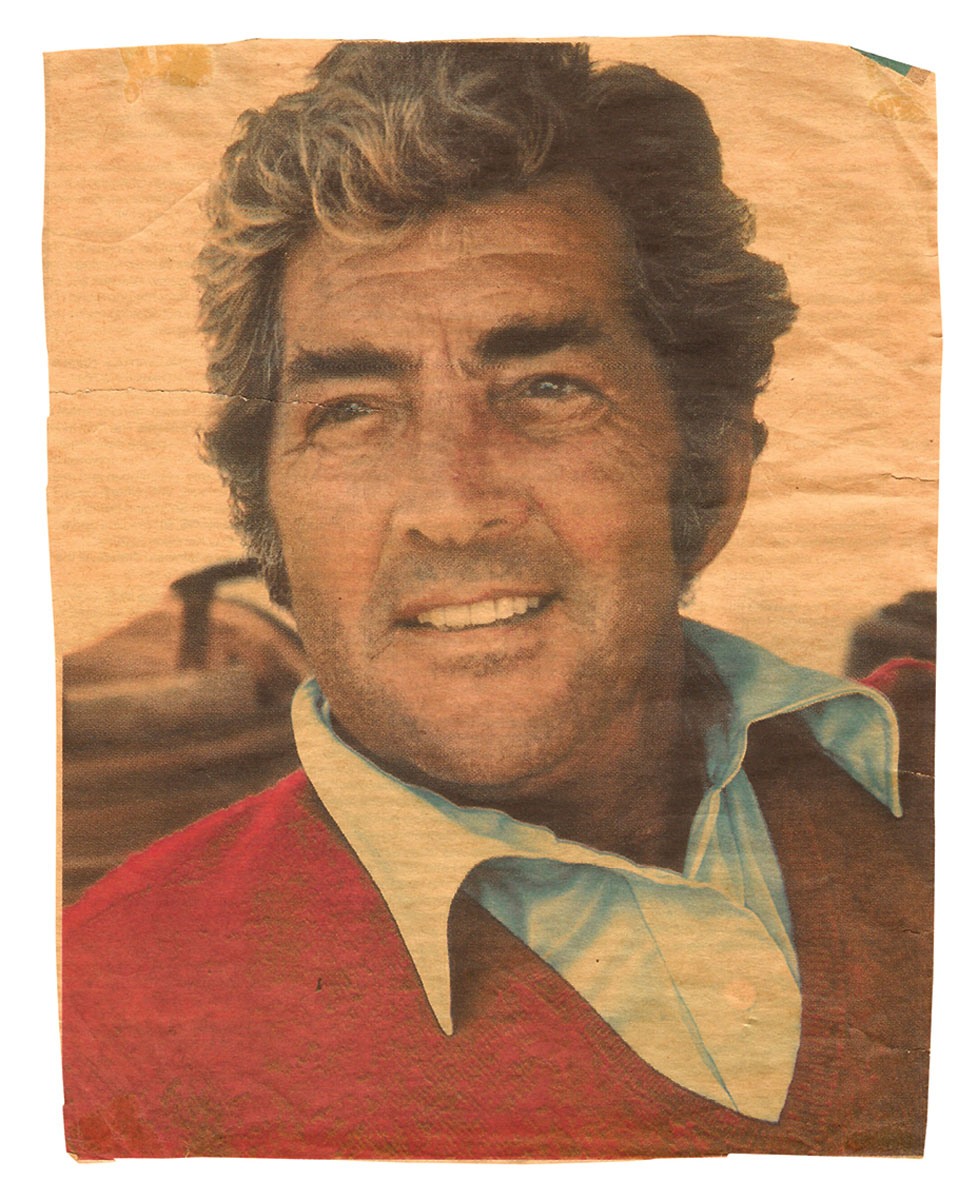

She’d recently had CCTV installed, she told me when I arrived. In the small stuffy sitting room, a monitor flickered away in black and white, and a camera on the windowsill was pointed at the front garden, its flowerbeds and neat sprung metal gate. In her living room at the back of the house an identical apparatus, the screen dominating the dining table and the camera trained on rosebushes, bird feeder, garden shed. Neither camera was attached to a recorder. I swear I felt dizzy at the thought—she must watch this stuff live. Could it be true? That in place of her soap operas and old movies with Victor Mature or Dean Martin, she sat down now to squint all day, unseen behind her curtains, at these squarish gray screens, fearing and hoping to see movement from the hedge, a figure dart into view, the crime itself in process? All that was needed was for her neighbors to point a similar camera through a gap in the hedge, and they would have set up between them a perfectly reflexive video loop, capable of staring itself down for another forty years. Perhaps for now she just liked to feel that there was somebody there.

(When she died, we discovered Dean Martin, cut from the TV pages of the evening newspaper and taped to the living room wall, just above the place where Daddy used to sit. Dean Martin: the blithest, laziest, most heedless of stars—her idea of a real man, in the end.)

There are forms of keen, habitual, and even morbid attention to the world around us that don’t merely preclude self-examination or disallow self-knowledge, but rather stand in for a close look at our lives and a proper expression of what we find there. If I cannot exactly sympathize with her anxiety and aggression, I understand perfectly her methods and the state of mind necessary to such a protracted act of close looking. For half her time on earth, she never stopped paying this attention, never ceased to examine for clues the shrinking world in which she lived, in which she had, as we say, ended up. For the simple reason is—but there are no simple reasons. Hers was not much of a life, half a life maybe. For sure, she ought to have been rescued from eking it out like this at the last, in anxious trips to the pharmacy to collect her prints and examine the latest evidence, hours and days spent staring at her screens or quiet at her windows, like some haggard self-consuming specter out of late Beckett.

She thought she had disinherited me, but I am not so sure. I share her tendency to hypochondria: a bout of it every few years, whole weeks and months disappearing in a welter of vigilance and dread. What else? A history of periodic isolation verging on agoraphobia. A habit of erecting barriers of fragile dignity and forms of anxious attachment—to certain objects, for instance—when I feel myself threatened. And more. Her obsessive and solitary looking, her fretful listening, her poring over pictures and locking the world away so she could address it only in letters of complaint: it all feels quite familiar. You can pursue vigilance and attention into a kind of fugue state, almost hallucinatory, maybe fully so in her case. It’s the family curse, you might say, this turning from the world and peering at nothing or next to nothing until it gives something up, some objective correlative. We’ve all done it; it’s how we pass the time: we’re quite as mad as she was. I spend my days staring at the screen and hoping something will appear. I call it work, and she called it—what? The way things were.

Afternoon turned to evening as I sat listening to her decades-old complaints. On the table in front of me the screen darkened slowly till a streetlight came on, and headlights streamed in the distance.

Brian Dillon, UK editor of Cabinet, teaches critical writing at the Royal College of Art. Recent books include Objects in This Mirror: Essays (Sternberg Press, 2014) and Ruin Lust (Tate Publishing, 2014). His writing has appeared in the Guardian, the London Review of Books, and frieze. The Great Explosion will be published by Penguin in 2015, and Essayism by Fitzcarraldo Editions in 2016. He lives in Canterbury.