Ingestion / The Chromatic Palate

Tasting with the eyes

George Pendle

“Ingestion” is a column that explores food within a framework informed by aesthetics, history, and philosophy.

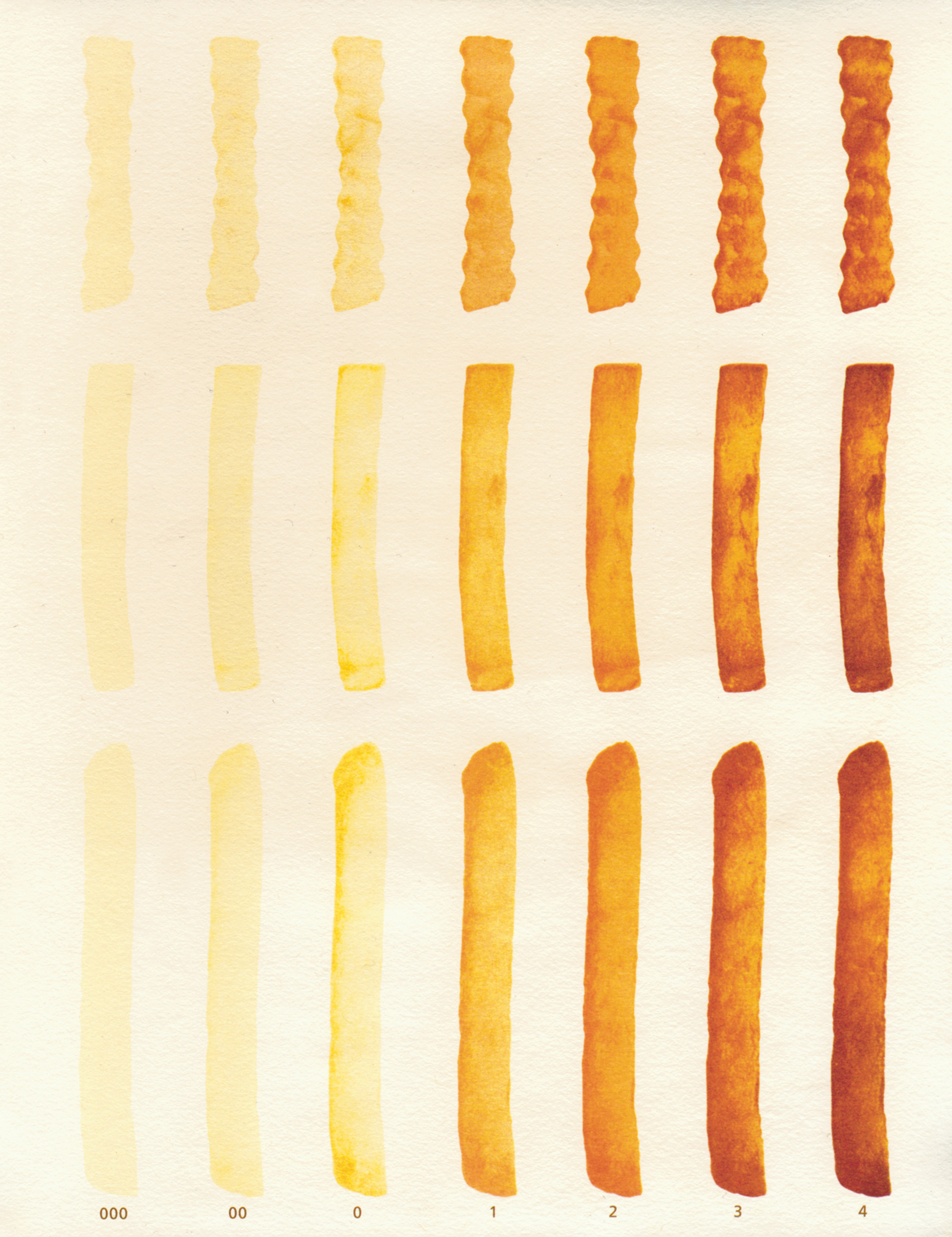

The United State Department of Agriculture Color Standards for Frozen French Fried Potatoes depicts three different types of fry—crinkle-cut, straight-cut, and extra-long fancy-cut—cooked to seven different shades. There is the blanched and insubstantial “000,” more pomme d’air than pomme de terre, that seems julienned from the breath of the ghost of a potato. There is “1,” the platonic french fry, as perfectly tanned as a matinee idol; it demands, almost pleads, to be reverse piked into a glistening pool of ketchup. And then there is the grubby bronze of “4,” the creation of a short-order deity who lingered too long over his creation, a Caliban among the spudocracy.

This chart, produced by Munsell Color, is intended not only to act as a guide to determine the finishing point of frying (how long must we wait before we can ask for a quiver of 00s with our hamburger?) but also, and more importantly, to help in evaluating the quality of the product. This is because our ideas of freshness and quality are bound up in a foodstuff’s color: a red apple entices us, a black banana disgusts us. We are trained, to an almost instinctual level, to reject some food and accept others by sight alone. Unfortunately, our overwhelming reliance on these visual cues has led to centuries of deception by purveyors of chow.

In the Middle Ages, bread was regularly whitened with chalk and bone dust to make it appear as if it had been baked with refined white flour. In Victorian times, pickles were customarily given their green color through being impregnated with copper, and milk was so regularly tinged a creamy yellow with lead chromate that many refused to buy the genuine white article for fear that it had been adulterated.

So strong are our visual biases, and so crooked our souls, that sometimes color was added to food for quite the opposite reason. When margarine was invented in the late nineteenth century, its manufacturers colored it yellow (it is naturally white). Its sales soared. Bitter butter manufacturers were outraged—despite the fact that most butter was colored too—and sought to destroy the upstart spread. Five dairy-rich states passed into law legislation that all margarine henceforth be dyed pink, ostensibly so that consumers would not mistake it for butter but actually to destroy its integrity. It was no coincidence that a cow sick with mastitis produces pink milk.

With the invention in 1856 of the first organic dye, mauveine (from which mauve originates), yet more ways became available to hoodwink, and poison, the consumer. In the landmark 1910 legal case, US v. 1,950 Boxes of Macaroni, the defendant was found to have been dyed with Martius yellow, a poisonous organic compound used for dying wool and silk. It was not long before all color additives had to be approved by the fledgling Food and Drug Administration (FDA).