A Packed Theater

Salvaging Munich’s Residenztheater

Augusto Corrieri

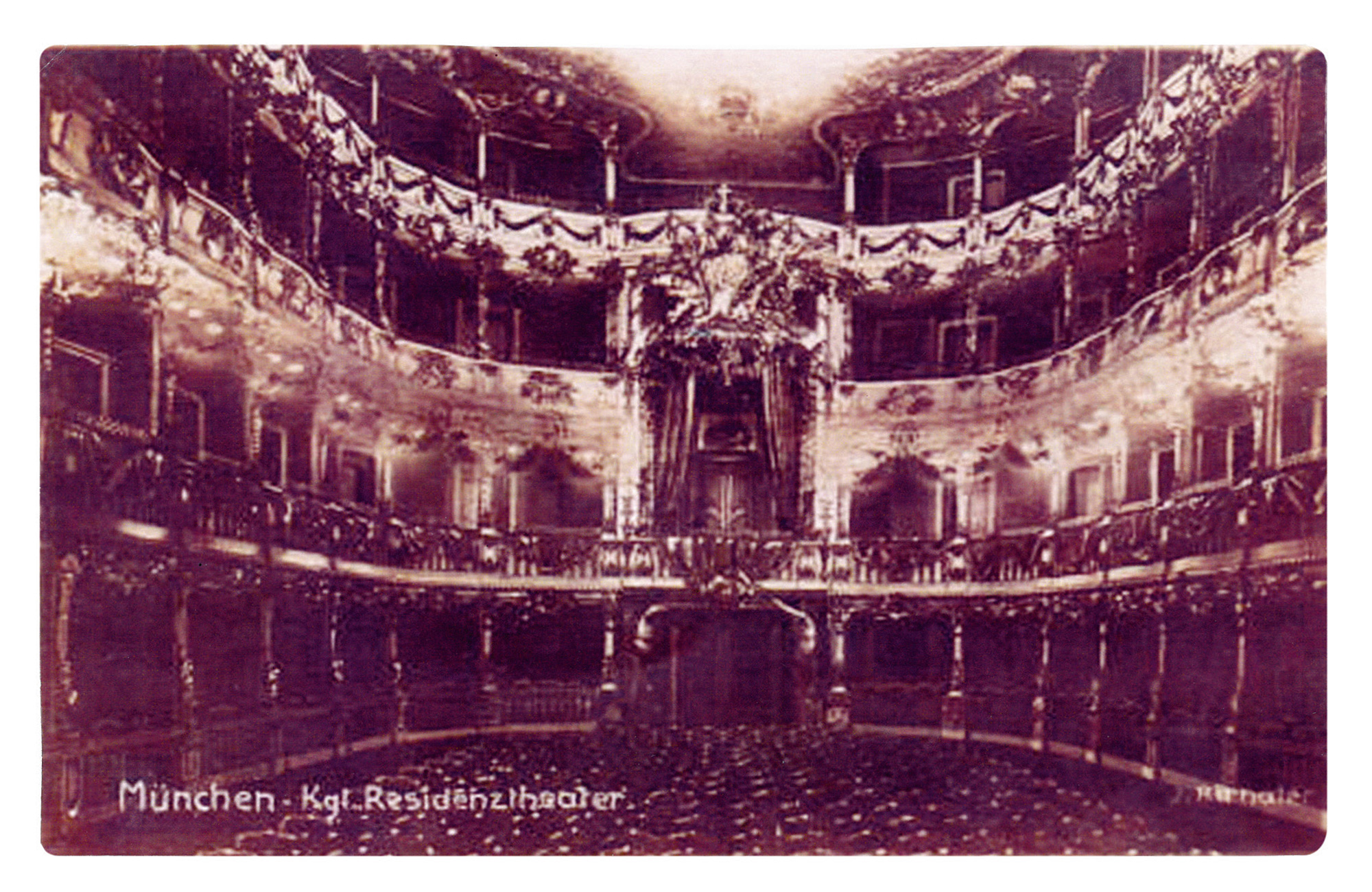

In 1944, Munich was suffering heavy bombing by the Allied forces. Fearing the destruction of the theater and its lavish rococo decor, the city’s administration acted to safeguard it for future generations: the entire auditorium was dismantled “into some thirty thousand pieces,” packed into wooden crates, and hidden outside of the city.[1] On 18 March 1944, only six weeks after the theater had been successfully concealed, the site was indeed bombed, but by that point it was mostly an empty shell. After the war, the auditorium’s fragments were recovered and meticulously reassembled, enabling the theater to reopen its doors in 1958. The bottom image shows the theater as it stands today.

A simple paradox, whereby Munich’s Residenztheater managed to stay in place by being displaced, to survive the bomb through the labor of fragmentation.

The dismantling of the auditorium can be likened to a simulated detonation, an act of rubble making that preempted the explosion to come. What was rehearsed through that careful demolition was the scene, infinitely slowed down, in which a bomb falls onto and shatters a theater, its various fragments flying off in different directions.

Or we could say: a meticulously planned fictitious explosion took the place of the real one, recasting the bomb that did eventually fall on the site as no more than a hollow sound effect, echoing across a city that was genuinely turning to rubble.

The Befreiungshalle’s imposing interior features eighteen white angel statues, their hands joined around the hall’s perimeter, each five meters tall. Their number commemorates 18 June 1815, when Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo; given the hall’s evocation of military heroism, it was frequently used during the 1930s for large National Socialist gatherings.

What matters in this narrative is that large cases containing the theater’s decor would have been stacked in the center of the hall, encircled by those angel statues, their linked hands physically enacting the gesture of protection. The Residenztheater was thus relocated inside the Befreiungshalle, a task not without a certain poetry, given that it essentially entailed moving a large auditorium inside a much smaller hall. It was a case of material synecdoche, whereby the boxed decor represented the whole theater building.