Kiosk / Fall 2015

In the nooks and crannies

Cabinet

Late again, late once more, late we are. We are writing this installment of Kiosk for the Fall 2015 issue as the winter of 2016 draws to a close. We have only ourselves to blame, but since we control these two pages, we’d like to take this opportunity to blame others. We are late, in part, because over the past two years we have increasingly become vassals to a new and powerful cultural overlord, namely the film and television industry. In this pageant, we neither act nor direct. Nor are we extras, though we do feel extraneous. The truth is that we are, lamentably, located roughly a hundred yards from a newish and very busy film studio. As often seems to be the case, said film studio provides no parking of its own, instead relying on their clients to obtain permits from the Mayor’s Office of Film, Theatre & Broadcasting (MOFTB) to use, often five days a week, some six to eight entire blocks around us to park their oversized trailers and food trucks. Since our shabbily picturesque neighborhood screams “rundown American city, ca. 1980,” it is also often used for location shoots by the studio’s largest client—FX’s television series The Americans. Some time ago, exasperated by the fact that on several occasions we could not enter or leave our space during shoots because our anachronistic presence would disrupt the show’s “period feel,” we spoke to one of the producers of the series, who informed us that if we wished to come and go as we pleased, all we needed to do was to groom ourselves and dress in a manner appropriate to the early 1980s. Our next grant application thus includes a request for $2,000 for cowl-neck sweaters, leg warmers, and spandex shorts.

• • •

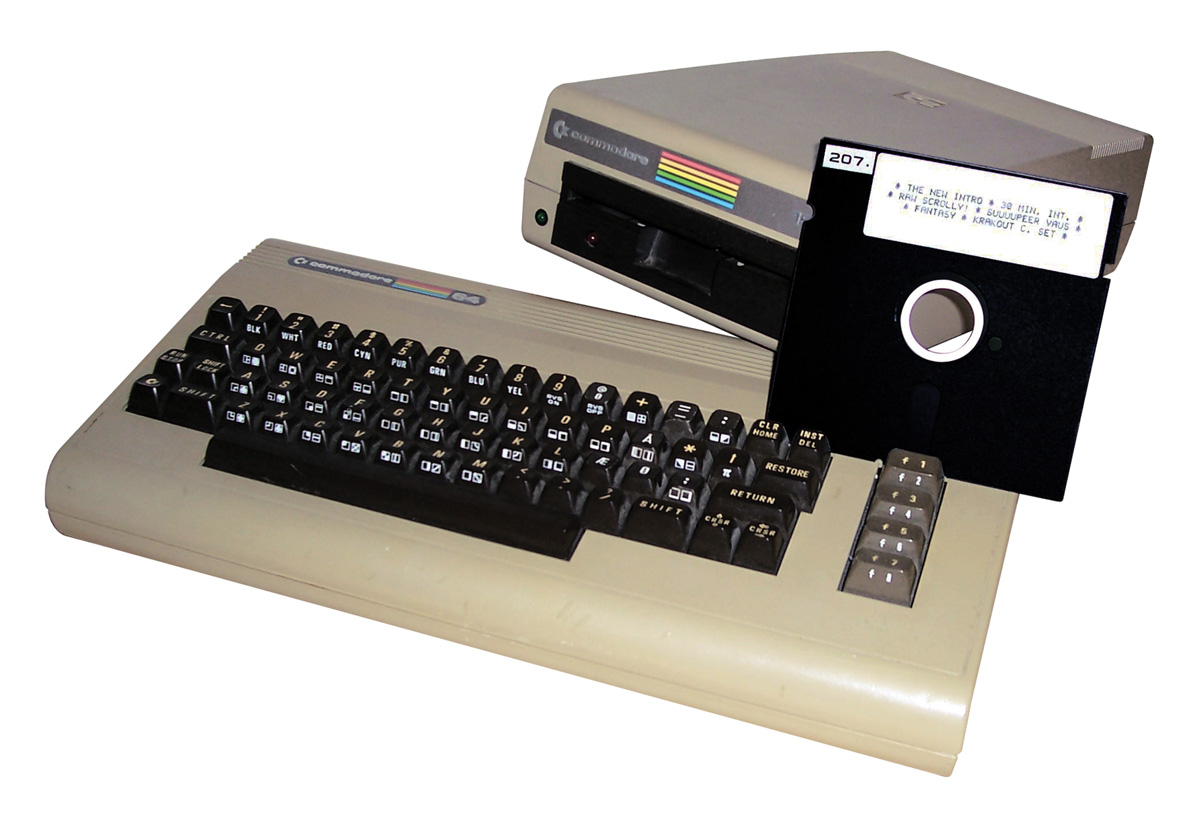

Others in the neighborhood, more reluctant to relive the sartorial horrors of the early 1980s, banded together last year and sent a petition to MOFTB asking for clarification on the process for issuing permits continuously in a neighborhood that has so many active small businesses reliant on deliveries. This petition received no response, though public statements made by the head of that office, Cynthia Lopez, and her henchman Dean McCann clarified all too well their policies. When the pair appeared in January 2015 at a hearing convened by New York’s City Council to consider a bill requiring MOFTB to provide compiled data on the number of parking and film permits issued in each neighborhood, Lopez claimed that though her office was committed to government transparency, she was concerned that said transparency would “send a complicated message to the productions.” Henchman McCann concurred, adding that “on the face of it, this bill is harmless. It’s the next step with regard to what people do with the data that is of extreme concern, not only to the mayor’s office, but to the industry.” Neither was it always possible to provide citizens with advance notification of parking restrictions because films and television series often finalize their plans at the last minute: the “script that’s going to be shot for the next episode of Law and Order,” he helpfully pointed out, “hasn’t been written yet.” McCann also claimed that providing this data was, in any event, technically impossible, since MOFTB’s system had in fact been designed to generate permits, but not account for them. So perhaps it’s not just the early 1980s here on Nevins Street, but also at City Hall, which is apparently still using typewriters and adding machines. We are therefore budgeting a further $2,000 of our next grant to purchase a Commodore 64 computer for MOFTB.

• • •

Speaking of transparency, it’s time for a confession. We have recently come to realize that we, the editors, have absolutely no idea what we mean when we date an artifact using the familiar term “circa.” What does “circa 1850” mean? That the artifact was made between 1849 and 1851? Between 1845 and 1855? And why does “circa” feel like it indicates a narrower range when used with a year that is not a round number? Why does “circa 1849,” for example, suggest a frame of one or two years rather than five or ten?

To make matters worse, the further back in time you go, the more elastic the term seems to become. “Circa 8000 BCE” is certainly not likely to be describing a date between 7995 BCE and 8005 BCE. And don’t even get us started on “circa 1,000,000 BCE.” If these impressions are accurate, how can this ubiquitous little editorial shortcut ever be used transparently? In an attempt to codify a policy, we consulted a number of catalogues published by one of the most august cultural institutions in the world—the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And lo and behold, it became clear that they too were totally befuddled as to how to consistently apply this pesky word. Let it here be known that we are currently compiling a circa policy, and that this policy will be posted online, ca. 2016, so that inordinately curious readers can understand the range of years we intend to imply when using this vexing term in different temporal contexts.

• • •

Coming back to our (circa) Fall 2015 issue, we were pleased, though also spooked, to have recently found what seems to be one potential solution to our own ongoing anachronism. Four months before going to press, a Google Alert informed us of a miraculous development: the very issue you have in your hands was already available for download from a somewhat shady-looking website, even though we had not even begun editing it. We were too cowardly to click on the ensorcelling link, fearing not just viruses but also that the phantom issue might be better than anything we ourselves could make.

In light of this curious rip in the fabric of space-time, we wish to let Dean McCann know that scripts for all future films and television series are in fact available online before they are written, thus making it possible for him to let the good citizens of New York know a few days in advance that they will be screwed, instead of finding out as it is happening. Unlike us, McCann will probably be safe from viruses—his fancy new Commodore 64 will no doubt confound any contemporary malware that he might encounter on his journey into the wilds of the World Wide Web.